Abstract

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a non-communicable disease (NCD) with high morbidity and mortality, commonly observed worldwide. Understanding its molecular mechanisms and identifying potential therapeutic targets are crucial for disease screening, diagnosis, and treatment. In this study, we conducted a meta-analysis of multiple genome-wide association studies (GWASs) to identify genetic variants associated with AAA and explored the functional implications of these variants in disease pathology. We identified differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) and transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) analyses. Using these DEGs, we constructed an AAA-related protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and prioritized key genes for further analysis. Furthermore, we performed drug repurposing by identifying drug-gene and drug-protein interactions in existing databases and validated potential candidates through molecular docking. Our findings reveal 42 novel disease-associated SNPs and 52 previously unreported disease-related genes. Some residual confounding factors cannot be fully ruled out and may represent a limitation of our study. However, it is worth noting that only a minority of SNPs exhibited heterogeneity. Functional pathways analysis highlighted key processes, including lipid and cholesterol metabolism, tissue remodeling, and acetylcholine activation. We identified 74 DEGs through eQTL and TWAS analyses, with PPI network analysis highlighting CD40 and LRP1 as key proteins. Drug repurposing and molecular docking suggested abciximab and paclitaxel as potential therapeutic agents targeting CD40, while ivermectin emerged as a strong candidate for LRP1 binding. In conclusion, our integrative bioinformatics frameworks links genomics and transcriptomics with network biology and structural modeling, providing valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of AAA and potential therapeutic strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a critical public health concern, with an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 deaths per year worldwide between 1980 and 20171,2. The high morbidity and mortality rates associated with ruptured aneurysm can be prevented by early diagnosis3,4,5. AAA, a localized and permanent dilatation of the abdominal aorta, is typically diagnosed when the aortic diameter reaches 30 mm or greater6,7. It is most prevalent in males aged over 658. Previous studies have identified a positive family history, smoking, genetic factors, and high blood pressure as significant risk factors contributing to the disease9,10. Screening high-risk populations with ultrasound has been investigated as an effective approach to preventing aneurysm-related mortality11,12. Despite progress in endovascular surgery, the absence of definitive pharmacological treatment for AAA emphasizes the need for further exploration of critical pathological mechanisms13,14.

Recently, genomic approaches using bioinformatics analysis have played an important role in the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of several diseases. In AAA, various studies incorporating molecular genetics have investigated genetic risks and the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease. For instance, a candidate gene case-control study has identified numerous genetic variants linked to AAA, although replication in other genes has been limited15. Recent advancements in high-throughput genomic technologies have facilitated genome-wide association studies (GWASs), where common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are examined in cases and controls using a hypothesis-free approach to identify genetic loci associated with complex diseases16. Previous studies have identified three novel loci on chromosome 9 (DAB2IP: DAB2 interacting protein17), 12 (LRP1: Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 118), and 19 (LDLR: Low-density lipoprotein receptor19). Additional risk loci have been annotated on chromosomes 1 (SORT1: sortilin 120 and IL6R: interleukin 6 receptor21), chromosome 2 (ATOH8: Atonal bHLH transcription factor 822), chromosome 5 (LINC01021: Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 102122), and chromosome 9 (CDKN2B-AS1: CDKN2B antisense RNA 123 and JAK2: Janus kinase 222). Nevertheless, analyses from individual small GWASs have rarely identified causal genes mediating the effects of variation on traits24. Although large-scale GWASs have identified 24 genomic risk loci for AAA through a meta-analysis of GWAS data17,18,19,25,26, the identified variants explain only a minority of the genetic risk27. To discover additional genetics risk loci, meta-analysis of GWAS data has been developed to improve statistical power by integrating several GWASs to increasing sample sizes.

Discovery of risk loci from individual and meta-analysis GWASs is essential for disease screening and prediction. Nonetheless, these methods alone are insufficient for identifying the molecular mechanisms behind the disease and targeting genes for treatment. Therefore, functional and systematic approaches are needed for biological pathway analysis. For example, transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) based on GWAS datasets by constructing predictive models28. Functional mapping and annotation (FUMA) is a web-based tool that analyzes functional enrichment pathways based on annotated genetic risk loci from GWAS results29. This platform also provides information on expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), which are genetic loci relevant to variations in gene expression. Network biology constructs a graph data structure based on biological entity relationships30, offering several benefits for gene prioritization and drug discovery. Some studies prioritize genes or proteins using graph parameters such as degree and betweenness centrality31,32,33. Once key genes or proteins are identified, finding candidate drugs that interact with them is necessary to develop targeted treatments. However, some candidate drugs are chemical compounds not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), requiring time and cost for safety evaluations. Drug repurposing is a preferred approach, as it focuses on existing drugs known to treat other diseases34, reducing both cost and time. Afterwards, structural modeling of key proteins also plays a vital role in confirming drug-protein interactions, such as calculating binding parameters through molecular docking35.

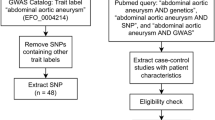

In this study, we applied GWAS summary statistics from three studies, encompassing approximately two million samples, in a meta-analysis to identify the genetic variations (SNPs) associated with AAA. Functional enrichment and genetic risk loci annotation of the associated variants were performed to uncover the mechanisms and pathways contributing to the disease. Additionally, TWAS was utilized to prioritize and identify DEGs associated with AAA by integrating GWAS summary statistics with eQTLs analysis. A biological network generated from the DEGs was employed to discover molecular relationships and prioritize genes using graph algorithms for exploring vital pharmacological target genes. Drug repurposing from database searches was operated to find possible interactions between key genes or proteins and FDA-approved drugs. Molecular docking was then used to screen potential drugs against the targeted proteins obtained from network analysis. The screened drugs were selected to elucidate the interaction profiles and key interacting residues. Therefore, this study demonstrates how bioinformatics frameworks can be integrated to unveil genetic risk loci, disease-related pathways, prioritized genes, and target drugs for AAA, merging genomics, transcriptomics, biological networks, and structural biology (Fig. 1). We hope this integrated strategy provides a valuable pipeline for detecting novel genetic risk loci, identifying therapeutic targets, and advancing drug discovery against various diseases.

Materials and methods

Data collection and pre-processing

The GWAS summary statistics datasets utilized in our study are summarized in Table 1. All three datasets were retrieved from the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/search, accessed on 3 April 2024)36. The first dataset is derived from the Global Biobank Meta-analysis Initiative (GBMI) collaborative network37, which includes a large sample size (cases = 8,163; controls = 1,256,755; total sample size [N] = 1,264,918). Moreover, we applied the second dataset, a study on gene-trait associations based on exome sequencing of UK Biobank participants38 (cases = 1184; controls = 386,746; N = 387,930). The third dataset, a GLMM-based GWA tool GWAS39 (cases = 556; controls = 455,792; N = 456,348), was also incorporated in this study. The combined sample size of our meta-analysis is N = 2,109,196 (cases = 9903; controls = 2,099,293). Power calculations were performed using the genpwr package in R40, based on an expected odds ratio (OR) of 1.4, a significance level of 5 × 10⁻⁸, and an additive model. The OR was adapted from the average odds ratios (1.33) of statistically significant SNPs reported previously41. All summary statistics consist of effect sizes, standard errors, and p-values for SNPs associated with AAA. The SNPs that were present in all three datasets with identical alleles were included in the meta-analysis. SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) < 0.01 have already been excluded from the summary statistics in the original studies, as confirmed through the literature review. SNPs were harmonized across datasets to ensure that all studies used the same reference allele. The genome coordinates in all datasets were converted for consistency from GRCh37 to GRCh38 using LiftOver in the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgLiftOver, accessed on 5 April 2024)42 before meta-analysis.

GWAS meta-analysis

Meta-analyses across the studies were performed using METAL v2020-05-0543. I2 and Cochran’s Q statistics were tested for SNP heterogeneity using METAL. Sample-sized based models were used in this analysis, weighting studies according to their sample sizes. This sample size-based meta-analysis enables the combination of p-values from results even when the β-coefficients and standard errors from individual studies are in different units. Stouffer’s method43 was applied in METAL to meta-analyze the summary statistics. We used a genome-wide significance threshold of p-value < 5 × 10⁻8 for GWAS meta-analysis, which is a widely accepted standard to correct for multiple comparisons in large-scale association studies44,45. This threshold is based on a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, accounting for approximately one million independent common SNPs across the human genome. We also applied a significance threshold of p-value < 1 × 10⁻5 as a suggestive or alternative threshold. The suggestive threshold is used solely to highlight potentially interesting variants for further investigation, but it does not indicate a definitive association with the condition of interest. Manhattan and quantile–quantile (QQ) plots were generated using the qqman package in R46.

Identification of independent significant SNPs, lead SNPs, and genomic risk loci and eQTLs mapping

FUMA (https://fuma.ctglab.nl/, accessed on 7 April 2024)29 was employed for genomic risk loci mapping, gene-based statistics calculation, and functional annotation of the GWAS results, employing default settings. The program has two main modes: SNP2GENE and GENE2FUNC. The first mode was used to identify lead and independent significant SNPs, as well as genomic risk loci and eQTLs mapping. Parameters related to linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks, such as r2 and MAF, were computed using the 1000 Genomes Project Phase 3 EUR as the reference panel. Independent significant SNPs were defined as those with a p-value below the genome-wide significance threshold (5 × 10⁻⁸) with r2 < 0.6, while lead SNPs were independent significant SNPs with r2 < 0.1. Genomic risk loci were characterized by grouping independent significant SNPs with r2 > 0.1 into the same loci. Additionally, other independent significant SNPs within 250 kb of these loci were included. Gene expression data of aorta tissue from GTEx v8 was used for eQTL mapping. FUMA mainly annotates cis-eQTLs, which are all independent significant SNPs located near genes that regulate gene expression. The software maps SNPs to genes up to 1 Mb. Significant SNP-gene pairs, with FDR < 0.05, were considered cis-eQTLs.

Functional enrichment analysis using MAGMA and GENE2FUNC

MAGMA47, integrated in FUMA, was used to analyze gene-set enrichment, incorporating curated gene sets and gene ontology (GO) terms from the Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB v7.0). In functional enrichment analysis using MAGMA gene-set analysis, pathways with Bonferroni-corrected p-values < 0.05 were considered significant to control for false positives based on the default setting of the program. The gene window in MAGMA was set to 10 kb upstream and downstream to cover SNPs located in the cis-regulatory regions of genes. MAGMA was also utilized for the analysis of tissue-specific expression among GTExv8 tissues48. Furthermore, the second main mode (GENE2FUNC) in FUMA was employed to analyze the mapped genes from SNP2GENE for their average expression across GTEx v8 tissues. This was visualized in a heatmap with hierarchical clustering using the average method and the unweighted pair group method with the arithmetic mean approach (UPGMA) for genes and tissues. We also evaluated enrichment against different gene sets using hypergeometric tests.

Single-tissue TWAS analysis and DEG identification

To investigate the association between AAA and the predicted expression of gene transcripts, a single-tissue TWAS analysis was performed using FUSION49. The software uses the predictive model from its training parameters and reference panels to predict SNP-gene mapping. FUSION performs the TWAS analysis using cis-SNPs with SNP-gene mapping within 1 Mb and matched in expression reference panels. The predicted model for expression in FUSION was derived from the meta-analysis summary statistics results from METAL, combined with common cis-eQTLs weights from aorta tissues in GTEx v848. FUSION also performs LD correction to remove SNPs redundancy using LD reference panels. The LD reference for Europeans50 was received from the 1000 Genomes Project. Manhattan and QQ plots were created using the qqman package in R46. Statistical significance in the plots was determined using Bonferroni correction based on the number of the total number of genes (p-value < 2.5 × 10⁻6). We also applied a suggestive threshold, similar to that used in GWAS analyses, using p-value < 6.25 × 10⁻6. This was determined by a Bonferroni correction based on the actual number of genes tested in the TWAS results.

DEGs were identified from both cis-eQTL results in FUMA and genes identified in TWAS using FUSION. To ensure an adequate number of DEGs for biological network construction in subsequent analyses and consistency in significance thresholds between the DEGs from TWAS and the eQTLs identified through FUMA, we applied the Benjamini–Hochberg correction to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Genes annotated from cis-eQTL mapping with FDR < 0.05, as well as significant genes in TWAS with FDR < 0.05, were considered DEGs.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction and gene prioritization

Human interactome information was downloaded from the STRING database v12.0 (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 18 April 2024)51. The dataset contains interactions between protein pairs and their combined scores. The combined score is a confidence score of protein interactions, considering from experiments, text mining, databases, co-expression, neighborhood, co-occurrence, and gene fusion. The score ranges from 0 to 1000. The interactome data was mapped with the DEGs obtained from the previous analysis. Only interactions involving protein pairs within the DEGs were used to construct an AAA-related PPI network. The network was visualized using the STRING database and Cytoscape v3.10.252.

NetworkX package53 in Python was employed for PPI network analysis. Two types of edge weights in the network were calculated based on the combined score of the interactions. The first type, the relationship weight, was calculated by dividing the combined score by 1000, normalizing the weight between 0 and 1. The second type, the distant weight, was obtained by subtracting 1 from the relationship weight. Thus, the distant weight is complementary to the relationship weight and vice versa.

Degree centrality was determined in the network based on the relationship weight. In a network, the degree centrality of a node is the sum of the number of edges adjacent to the node or, in the case of a weighted graph, the sum of the relationship weights of the adjacent edges. Nodes with a high degree are considered hub nodes, indicating their importance in the network. Betweenness centrality, another key parameter for identifying essential nodes, was also computed. Betweenness centrality measures a node’s role as a bridge or bottleneck in the network. Nodes with high betweenness centrality scores are critical because their removal could significantly disrupt the network’s topology. Betweenness centrality of a node is calculated as the sum of the frequencies of shortest paths between all pairs of nodes that pass through the node of interest, relative to the total number of shortest paths between those pairs. The distant weight was used to calculate betweenness centrality by considering the shortest paths according to Dijkstra’s algorithm54,55. Both degree and betweenness centrality were normalized before further analysis.

Gene prioritization was adapted from a method used in a study to identify key genes in a severe COVID19-related PPI network56. Nodes in the AAA-associated PPI network with degree or betweenness centrality greater than the 90th percentile of centrality scores were defined as key genes or proteins. In addition, nodes with both degree and betweenness centrality exceeding the 90th percentile were considered very important genes or proteins, which were subsequently used for structural modeling and drug target identification.

Drug repurposing based on the prioritized genes

The key genes or proteins identified in the previous step were searched in the drug-gene or drug-protein interaction databases to identify possible FDA-approved drugs that bind to these proteins. Five databases were applied to find these interactions: DrugBank (https://go.drugbank.com/, accessed on 23 April 2024)57, Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (https://idrblab.net/ttd/, accessed on 23 April 2024)58, Comparative Toxicogenomics Databases (CTD) (https://ctdbase.org/, accessed on 23 April 2024)59, GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/, accessed on 23 April 2024)60, and STITCH database v5.0 (http://stitch.embl.de/, accessed on 23 April 2024)61. All FDA-approved drugs with documented drug-protein or drug-gene interactions, as well as those shown to alter gene expression based on experimental validation, were collected. Drugs interacting with key proteins having both high degree and betweenness score from the AAA-associated PPI network analysis were selected for further computational structural analysis in the subsequent method.

Computational studies of repurposed drugs and antibodies binding to critical genes

The targeted genes for structural modeling, cluster of differentiation 40 (CD40) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), were identified based on their high degree and betweenness centrality from the PPI network analysis. Molecular docking was performed to elucidate the mechanism by which repurposed drugs inhibit the PPI between CD40 and CD40 ligand (CD40L) and upregulate LRP1 expression. Protein crystal structures used in our study were obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/, accessed on 30 April 2024)62. The crystal structure of CD40 in complex with CD40L (PDB ID: 3QD663) was prepared as the protein receptor for the molecular docking of the anti-human CD40 antibodies, which included potent candidate compounds as well as previously reported anti-CD40 agents (bleselumab64 and dacetuzumab64). Meanwhile, CD40L (PDB ID: 3LKJ65) was employed for docking repurposed drugs and previously reported compounds (suramin66 and BIO889865) to block the CD40/CD40L interaction. For LRP1, two binding subunits, CR56 (PDB ID: 2FYL67) and CR17 (PDB ID: 2KNX68), were utilized for docking with candidate drugs and a previously reported protein, the receptor-associated protein (RAP)67. The protonation state of proteins was configured at pH 7 using PDB2PQR web server69, whereas ChemAxon70 was used to calculate the negative logarithm of the acid dissociation constant (pKa) value of drugs. Consequently, both drugs/antibodies and the CD40/CD40L or CR56/CR17 subunits of the LRP1 protein were selected for docking studies using the HDOCK server (http://hdock.phys.hust.edu.cn/, accessed on 12 May 2024)71. The binding of drugs/antibodies to proteins was visualized using the PDBsum website72, Accelrys Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys Inc.)73, and the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Chimera package74.

Workflow of integrative bioinformatics frameworks for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). AAA genome-wide association study (GWAS) datasets were retrieved from the GWAS Catalog36 and subjected to meta-analysis using METAL43. Summary statistics from the meta-analysis were used to identify independent significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) via FUMA29. Gene-set enrichment analysis was conducted using MAGMA47. Transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) was performed using the FUSION pipeline49. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were determined based on genes that were significant in both the eQTL and TWAS analyses. An AAA-associated protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the DEGs and interactome data from the STRING database51 and visualized with Cytoscape52. Key nodes in the network were identified based on high degree and betweenness centrality scores, calculated using the NetworkX package in Python53. Drug repurposing candidates were identified through screening drug–gene and drug–protein interaction databases, such as DrugBank57, Therapeutic Target Database (TTD)58, Comparative Toxicogenomics Databases (CTD)59, GeneCards60, and STITCH database61, and shortlisted drugs were further evaluated via computational structural modeling and molecular docking simulations using the HDOCK server71. The structural modeling results were visualized by the PDBsum website72, Accelrys Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys Inc.)73, and the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Chimera package74.

Results

GWAS meta-analysis, genomic risk loci, and gene mapping

The statistical power analysis using the genpwr package indicated that the sample size used in this meta-analysis was sufficient, with an estimated power ranging from approximately 0.8 to 1 across MAF between 0.01 and 0.9 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Heterogeneity test from the GWAS meta-analysis using METAL43 showed that most SNPs had low I2 values (I2 < 25) from the I2 distribution curve (Supplementary Fig. S2). The percentage of SNPs with significant Q statistics (p-value < 0.05) compared total SNPs was 0.75. The heterogeneity results were illustrated in Supplementary Table S1. Despite low heterogeneity across the three datasets, the sample size from Zhou et al.37 (1,264,918) is dramatically higher than that of Backman et al.38 (387,930) and Jiang et al.39 (456,348). Therefore, we decided to perform the meta-analysis using the sample size-based model, which weights studies according to their sample sizes. The meta-analysis revealed that 24,765,714 SNPs were reported in the summary statistics (Supplementary Table S2). Figure 2 displays the Manhattan plot of the METAL results, and Supplementary Fig. S3 shows the QQ plot. There were 2,709 variants with p-values less than the suggestive significant level (1 × 10–5) and 389 of these had p-values below the genome-wide significant level (5 × 10–8). To address variant redundancy, we performed LD analysis using the SNP2GENE mode in FUMA29. After this process, we identified 47 independent significant SNPs associated with the disease (Supplementary Table S3). Most SNPs were located in intronic regions, followed by intergenic regions (Supplementary Fig. S4). Moreover, in comparison with the GWAS catalog36, we identified 42 novel disease-related SNPs that have not been recorded in the database. Table S4 in the Supplementary data provides a detailed summary of these predicted novel disease-related variants.

Manhattan plot of the meta-analysis results from the AAA genome-wide association studies (GWAS). Each point shows a variant tested for association with AAA. The x-axis illustrates the genomic position of the corresponding variant, and the y-axis displays the negative logarithm of the genome-wide association adjusted p-value. The adjusted p-value was obtained using the Bonferroni correction method. The horizontal red dashed line represents the genome-wide significance threshold (adjusted p-value = 5.00 × 10−8), whereas the horizontal blue dashed line indicates the suggestive significance threshold (adjusted p-value = 1.00 × 10−5). The plot was visualized using the qqman package in R46.

Furthermore, 23 genomic risk loci were annotated from FUMA (Fig. 3), with 26 lead SNPs identified within these loci (Supplementary Table S5). Chromosome 11 contributed the highest number of loci, while chromosome 6 contained the largest loci, approximately 800 kb. The highest number of SNPs were found on chromosomes 18 and 15, respectively. Additional information on the genomic risk loci is illustrated in the Supplementary Table S6. A total of 83 mapped genes were identified, 52 of which have not been previously associated with the disease in the GWAS Catalog36 or Gene Cards60 databases. The list of these novel genes is included in the Supplementary Table S7. The primary mapped genes were located on chromosomes 10 and 15 (Fig. 3). Additionally, 492 cis-eQTLs were annotated in FUMA (Supplementary Table S8). These eQTLs were subsequently used as DEGs to construct the AAA-related PPI network.

Bar plots of the identified genomic risk loci using FUMA based on the GWAS meta-analysis summary statistics. The y-axis represents the risk loci, annotated by chromosome number and genomic coordinates (start-end). The x-axis displays various features of each locus, including locus size, number of SNPs, number of mapped genes, and number of genes physically located within the locus. The plots were generated and visualized using the FUMA web-based platform29.

Functional enrichment and tissue expression analysis based on genomic results

Gene-set analysis from MAGMA revealed that the mapped genes primarily involved lipid metabolism. Table 2 provides the results of functional enrichment analysis generated with MAGMA. These results were concordant with the curated gene-set analysis from the GENE2FUNC mode in FUMA (Fig. 4). Additional pathways identified in the GENE2FUNC include extracellular matrix and soft tissue activities, such as matrix metalloproteinase activities, fibroblast activities in wound healing and tissue remodeling, and acetylcholine receptor activation.

Gene-set functional enrichment analysis was conducted based on the mapped genes from the SNP2GENE mode in FUMA. The enrichment analysis was performed in the GENE2FUNC mode. The y-axis displays significantly enriched functional pathways. The x-axis is divided into two parts: (1) bar graphs showing the proportion of overlapping genes within each pathway (red) and the –log₁₀(adjusted p-value) (blue), and (2) a heatmap indicating the presence of overlapping genes in each gene set, with orange marking genes present in the respective sets. P-values were adjusted using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. All plots were generated and visualized using the FUMA web-based platform29.

Tissue expression analysis in MAGMA showed that the gene expression patterns associated with our GWAS meta-analysis results were similar to those observed in the lung, gastrointestinal tract, artery, and fibrous tissue (Fig. 5A). These findings were consistent with the heatmap of tissue expression based on mapped genes from the GENE2FUNC mode in FUMA (Fig. 5B). The heatmap, which includes hierarchical clustering, shows that intestinal, artery, fibrous, and pulmonary tissues show similar patterns of high significant gene expression, in alignment with the ranked p-value tissue-specific expression in MAGMA. Additionally, the tissue expression results were relevant to the functional enrichment analysis, highlighting lipid metabolism and extracellular matrix activities, which are primarily associated with alimentary and fibrous tissue, respectively.

Tissue-specific expression analysis was performed using GTEx v8. The figures were generated and visualized using the FUMA web-based platform29. (A) A bar plot illustrates the significance levels across 53 tissue types, represented on the x-axis, as determined by MAGMA. The y-axis represents the negative logarithm of the adjusted p-value (–log₁₀ adjusted p-value). The adjusted p-value was obtained using the Bonferroni correction method. (B) A heatmap displaying the average gene expression levels (logarithmically base 2 transformed), with hierarchical clustering of the 83 mapped genes across GTEx v8 54 tissue types, generated using the GENE2FUNC mode in FUMA. The red and blue color spectrum represents the high and low expression, respectively.

Identification of DEGs and gene prioritization based on the AAA-associated PPI network

To identify DEGs involved in the association between disease and trait, TWAS were operated using FUSION49. The results of the predicted genes are shown in the Manhattan plot (Fig. 6), with the QQ plot of the TWAS analysis illustrated in the Supplementary Fig. S5. Ten transcripts surpassed the suggestive significance threshold (6.25 × 10−6), and nine of these, including TDRD10, STK36, THBS2, SUGCT, ADAMTS8, LPR1, IQCH, MRC2, and NEURL2, were annotated as known protein-coding genes. The details of these transcripts, including their functions and statistical results, are summarized in the Supplementary Table S9. Notably, several of these genes, such as ADAMTS8, THBS2, TDRD10, MRC2, and LPR1, have previously been reported in the context of AAA. The gene ENSG00000273466 could not be annotated in FUSION but was considered as a long non-coding RNA (lnc-ZNF142) in LNCipedia (https://lncipedia.org/, accessed on 23 June 2024)75. In addition, seven transcripts, including lnc-ZNF142 (ENSG00000273466), STK36, THBS2, SUGCT, ADAMTS8, IQCH, and NEURL2, had p-values below the transcriptome-wide significance threshold (2.5 × 10−6).

Manhattan plot of transcriptome-wide association study (TWAS) of AAA using FUSION49. The horizontal red dashed line indicates the transcriptome-wide significance threshold (adjusted p-value = 2.5 × 10−6), while the horizontal blue dashed line represents the suggestive significance threshold (adjusted p-value = 6.25 × 10−6). Each point shows a transcript tested for association with expression imputation from the METAL results. The x-axis displays the genomic coordination of the genes, and the y-axis illustrates the negative logarithm of the transcriptome-wide association adjusted p-value. The adjusted p-value was obtained using the Bonferroni correction method. Genes with adjusted p-values below the suggestive significance threshold (i.e., above the corresponding –log₁₀(p-value) line) are labelled with their gene names. The plot was visualized using qqman package in R46.

Additional significant transcripts were identified through the Benjamini–Hochberg correction by calculating FDR. An additional 51 transcripts had an FDR < 0.05. Therefore, a total of 61 DEGs from the TWAS analysis, along with 20 DEGs from the eQTL analysis in FUMA, resulted in 74 DEGs (Supplementary Table S10). Figure 7A shows a Venn diagram of DEGs from the TWAS and eQTL analyses. The AAA-associated PPI network was generated based on the DEGs using human interactome data from the STRING51 database (Fig. 7B). The largest component of the network, containing 59 proteins and 296 interactions, was used for further analysis. The degree and betweenness centrality of each node are detailed in Table S11 in the Supplementary data. Ten key proteins were prioritized based on centrality measurements, with degree or betweenness scores greater than the 90th percentile. Table 3 lists the key proteins, where proteins with high degree scores are considered hubs, and those with high betweenness scores are considered bottlenecks. Notably, two proteins, CD40 and LPR1, were identified as both hubs and bottlenecks.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and AAA-related protein–protein interaction (AAA-PPI) network. (A) Venn diagram displaying the DEGs identified from eQTLs in FUMA29 and TWAS in FUSION49. The mapped genes are also included in the plot. (B) AAA-associated PPI network constructed from human interactome data in STRING v12.051 and the identified DEGs. The network was visualized using Cytoscape v3.10.252. Edges represent various types of evidence supporting protein–protein interactions: curated databases (light blue), experimental data (purple), gene neighborhood (green), gene fusions (red), gene co-occurrence (blue), text mining (yellow), co-expression (black), and protein homology (periwinkle).

Repurposed drugs binding to the prioritized proteins to alleviate AAA progression

Repurposed drugs targeting the ten vital proteins were sourced from the TTD, CTD, DrugBank, GeneCards, and STITCH databases, as summarized in the Supplementary Table S12. A molecular docking study was performed to examine the binding of these repurposed drugs to two targeted proteins using the HDOCK webserver76. The validity of the program was ensured by redocking the crystal structure complexes of both vital proteins, as shown in the Supplementary Fig. S6 for CD40 and Fig. S7 for LRP1. Each drug was then assessed to determine its binding energy (∆Gbind) for CD40 and LRP1. Two distinct binding patterns were observed for CD40: the first involved repurposed anti-CD40 drugs binding directly to CD40, and the second involved the binding of drugs to CD40L. Both strategies may contribute to mitigating AAA progression.

The results revealed that abciximab exhibited the lowest binding energy (− 198.96 kcal mol−1) to CD40 among the candidate compounds, as well as in comparison with previously reported experimental anti-CD40 agents, bleselumab (− 158.64 kcal mol−1) and dacetuzumab (− 169.31 kcal mol−1), as depicted in the Supplementary Fig. S8. While paclitaxel demonstrated strong binding to CD40L with a binding energy of − 282.64 kcal mol−1 outperforming both the candidate compounds and previously reported agents, suramin (− 168.09 kcal mol−1) and BIO8898 (− 164.89 kcal mol−1), as shown in the Supplementary Fig. S9. Abciximab binding was particularly stable, facilitated by multiple interaction types, including strong hydrogen bond (H-bond) interactions with nine CD40 residues: K29, Q42, P43, Q45, E58, C59, G63, W71, and E98 (Fig. 8A,B). Additionally, a salt bridge formed with E58. Paclitaxel showed robust H-bond contacts with key residues of CD40L, including G226, Y170, and Y172 via domains A, B, and C, respectively (Fig. 8C,D). The ∆Gbind values and two-dimensional (2D) interactions of other repurposed drugs associated with CD40/CD40L are provided in the Supplementary Figs. S10, 11 and Table S13.

Key residues and critical interactions in the binding of repurposed drugs to CD40 and CD40L. Structural representation of (A, B) abciximab complexed with CD40 and (C, D) paclitaxel bound to CD40L. All molecular docking results were obtained from the HDOCK server and visualized using the PDBsum website72, Accelrys Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys Inc.)73, and the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Chimera package74.

Two crucial binding sites were identified on LRP1: the CR56 and CR17 subunits. Ivermectin represented strong binding affinity for both subunits, with ∆Gbind values of − 136.18 kcal mol−1 for CR56 (Fig. 9A,B), compared to the previously reported experimental protein, receptor-associated protein (RAP) (− 131.21 kcal mol−1), as depicted in the Supplementary Fig. S12. For CR17, the ∆Gbind value was − 118.59 kcal mol−1 (Fig. 9C,D). This binding affinity was supported by H-bonds with residues H82 and S13, in addition to several hydrophobic interactions. Further details regarding the binding affinity and key residues of other drugs targeting LRP1 can be found in the Supplementary Figs. S13, 14 and Table S13 in the Supplementary data.

The binding interactions and orientations of ivermectin with the subunits of LRP1 at the (A, B) CR56 and (C, D) CR17 active sites, along with HDOCK scores for both complexes. Molecular docking simulations were conducted using the HDOCK server, with subsequent visualization and analysis performed utilizing Accelrys Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys Inc.)73 and the UCSF Chimera package74.

Summary of key biological findings

As our study primarily involves intensive computational and theoretical approaches to identify molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets in AAA, some aspects may be challenging for readers who are not familiar with bioinformatics and computational biology. Therefore, we have summarized the key findings from each methodological step in a more biologically oriented manner. Our comprehensive GWAS meta-analysis identified significant genetic variants and novel risk loci associated with the disease, shedding light on potential new targets for research and treatment. To minimize the risk of misinterpretation due to insufficient sample size and heterogeneity in our GWAS meta-analysis, we assessed statistical power and heterogeneity. Our analysis revealed that the sample size was adequate, and the heterogeneity was relatively low. We discovered 389 variants with strong associations, many of which were previously unreported, along with 42 entirely novel disease-related variants. These findings expand our understanding of the genetic basis of the disease and provide a valuable foundation for future investigations. The identification of 23 key genomic risk loci and the mapping of 83 genes, including 52 novel ones, offers new insights into the molecular mechanisms driving disease development. The presence of these novel genes presents new opportunities for exploring their roles in the disease, potentially leading to the discovery of new biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

Furthermore, our analysis based on the GWAS summary statistics highlights the critical biological processes and tissues involved in the disease, with a particular focus on lipid metabolism and tissue remodeling. We found that the mapped genes are predominantly associated with lipid metabolism, which is vital for several cellular functions. Additionally, genes related to extracellular matrix activities, tissue repair, and wound healing were identified, further underlining the importance of tissue integrity and remodeling in the disease. The tissue expression analysis revealed that the genes most closely associated with the disease were highly resemble to the lung, gastrointestinal tract, artery, and fibrous tissue expression, suggesting that aorta tissue with aneurysm has functional pathways similar to those tissues. These findings not only confirm the involvement of lipid metabolism in tissues like the intestine but also point to extracellular matrix remodeling, similar to fibrous tissue, as crucial in tissues like the artery. Therefore, our study provides key insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the disease. By identifying critical pathways and tissues, we lay the groundwork for future research focused on these processes, which could lead to potential therapeutic targets and a better understanding of the disease’s progression.

In addition, by analysing how genetic variants affect gene expression, we identified 74 DEGs that are potentially involved in the association between disease and trait. These genes were discovered using a combination of two methods: TWAS and eQTL analysis. The TWAS approach revealed 61 DEGs, with several genes already known to be related to the disease. Additionally, 51 of these DEGs were found to be statistically significant. We further constructed the AAA-associated PPI network based on the identified DEGs, which helped us understand how these proteins might interact with each other. Within this network, we identified key proteins that play critical roles, either as hubs (high-degree proteins) or bottlenecks (high-betweenness proteins) such as PSMA4, CD40, PSMC3, LRP1, SCARA3, MRC2, PSRC1, ADAMTS7, FGF9, and MAP2K5. Notably, CD40 and LPR1 were found to be both hubs and bottlenecks, suggesting their central importance in the biological processes associated with the disease. These findings provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of the disease and may offer targets for future research or therapeutic intervention.

We identified candidate drugs interacting with the important nodes from the PPI network analysis by search on drug-gene and -protein interaction databases. The docking results revealed abciximab, paclitaxel, and ivermectin as promising candidates with high binding affinities to the key AAA-related proteins, suggesting their potential for therapeutic repurposing in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Overall, this study demonstrates the power of integrative frameworks in advancing the understanding of AAA pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies. These insights provide a valuable foundation for future investigations, encouraging further exploration through experimental validation and complementary computational approaches.

Discussion

Investigating diseases at the molecular level from various perspectives provides a comprehensive understanding of disease biology and facilitates the development of strategies for screening, diagnosis, and treatment. In this study, we integrated multiple bioinformatics frameworks, including genomics, transcriptomics, systems biology, and structural biology, to deepen our understanding of AAA biology. Moreover, we conducted drug repurposing by searching drug-gene or protein interaction databases and validated the results through molecular docking to identify candidate target drugs interacting with our prioritized genes or proteins.

We collected GWAS summary statistics data of AAA from three cohort studies in the GWAS Catalog36. For the METAL43 GWAS meta-analysis, the sample size included 9,903 cases and 2,099,293 controls. We calculated statistical power based on the combined sample size (2,109,196) and found that the power is high at between 0.8 and 1 when varying MAF from 0.01 to 0.9. Biases and confounding factors are one of the most important things to be considered in GWAS meta-analysis studies. A potential limitation of our meta-analysis is the variability among included cohorts in terms of ancestry, environmental exposures, and study design. Such differences may introduce heterogeneity in genetic associations. We then carried out the heterogeneity test in both I2 and Cochran’s Q statistics in our study and the result showed low heterogeneity among the three datasets. However, residual confounding from cohort-specific factors cannot be fully ruled out, and future ancestry-specific analyses are warranted even though all three GWAS datasets were derived from UK Biobank studies. LD analysis in FUMA29 was performed to remove redundant SNPs, resulting in the identification of 47 independent significant SNPs, 42 of which were novel and related to the disease. The novelty of these SNPs was confirmed by comparing with the existing AAA-related SNPs reported in the GWAS Catalog36. The reported disease-associated SNPs in the database originate from several GWAS and genetic variant experiment studies as well as meta-analyses involved in various types of aneurysms such as AAA, thoraco-abdominal aneurysm, and intracranial aneurysms17,18,19,25,26,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85. This highlights the effectiveness of GWAS meta-analysis in identifying new disease-related variants by enhancing statistical power. Based on the literature review, most of the predicted novel disease-associated SNPs have not been previously reported to be associated with aneurysms, metabolic syndromes, or other cardiovascular diseases. However, 12 SNPs have been previously reported in various GWAS studies to be associated with aortic diameter, serum lipid levels, and cardiovascular diseases. For example, rs35247409 was reported to be associated with ascending aortic diameter, suggesting its potential involvement in the development of AAA86. There are 7 SNPs related to triglyceride and cholesterol level such as rs646776, rs9989419, rs72786786, rs186696265, rs1864163, rs4970834, and rs14384342987,88,89,90,91,92. Disturbances in lipid metabolism have been considered contributing factors in AAA progression, potentially linking the associated SNPs to the disease93,94. Other variants, for instance, rs646776, rs10811650, rs56393506, rs4845625, and rs10757279, have been studied to associated with coronary artery disease (CAD)95,96,97,98,99. Several studies have shown that AAA has a strong association with CAD as both conditions share common risk factors100,101. CAD is also considered an independent risk factor for AAA100.

Furthermore, genomic risk loci and gene mapping identified 52 disease-associated genes that have not been previously recorded about AAA association in gene databases, reinforcing the advantages of meta-analysis. To confirm the novelty of the disease-associated genes, we compared them with previously reported AAA-related genes in the GWAS Catalog36, which includes genes mapped from known disease-associated SNPs. Additionally, we compared the predicted novel genes with known disease-associated genes from GeneCards60, an integrative database that compiles information on human genes, including their functions, locations, roles, and disease associations. Potential implications of our findings for AAA diagnosis were also discussed. Several GWAS studies have shown the application of disease-related SNPs as genetic biomarkers in various diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, COVID-19, and hepatitis C102,103,104. The predicted SNPs and genes could contribute to AAA prevention and precision medicine in the genomic era by enabling the identification of genetic biomarkers through variant analysis and interpretation. However, further experimental and clinical studies are required to validate these predictions. In our predicted novel disease-associated genes, most of them have the functions related to cellular homeostasis activity such as vesicular transportation, DNA replication, and RNA translation. These genes are still required for further research of the role in AAA pathogenesis. However, some predicted genes could contribute to the disease development. For instance, CHCHD1 and PARK2 mutations can cause cell injury or death due to mitochondrial dysfunction105,106. ZSWIM3 encodes a regulator in macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses107. Dysfunction of this gene may cause uncontrolled macrophage-mediated injury in aortic tissue. PLTP plays a role in phospholipid transportation from VLDL to HDL108. Mutation in this gene could cause abnormal lipid metabolism which is one of the contributing factors in AAA progression.

We also identified five main chromosomes contributing dramatically to the number and size of the genomic risk loci, SNPs, and mapped genes: chromosomes 6, 10, 11, 15, and 18. Previous studies have linked chromosome 11 with familial abdominal aortic aneurysm109,110, and chromosome 6 deletions to AAA111. Pathogenic variants of the FBN1 gene on chromosome 15 are implicated in Marfan syndrome, increasing the risk of both thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms112. Although no direct association between chromosome 10 and AAA has been reported, it has been studied in relation to familial thoracic aortic aneurysm113,114. Additionally, chromosome 18 has been linked to genetic regions relevant to bicuspid valve development115,116.

Functional enrichment analysis based on SNPs and mapped genes was generated using MAGMA47 and GENE2FUNC mode in FUMA to enhance our understanding of the molecular functions associated with complex SNPs and genes. The enrichment results were primarily related to cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism, which is consistent with AAA’s disease mechanisms involving plasma lipoproteins and lipid metabolism117,118,119. Several GWAS meta-analyses have shown that SNPs, associated with lipid transportation-related genes such as APOE, LDLR, LPL, PCSK9, PLTP, SCARB1, HMGCR, and CETP, are considered as variant risk loci related to AAA pathology117,118,120,121. Dysregulation of lipid and cholesterol metabolism induces oxidative stress and inflammatory processes in arterial tissue, leading to vascular damage and weakening93,94. Oxidative stress also results in lipid peroxidation which is commonly found in AAA. Lipid peroxidation is associated with necrosis and apoptosis of aortic tissue93. Furthermore, cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), a key enzyme in lipid peroxidation, has been related to a role in promoting aortic remodeling122. In addition, extracellular matrix and matrix metalloproteinase activities were discovered, emphasizing their role of tissue remodeling in AAA pathogenesis123,124. Enrichment was also observed for acetylcholine receptor activation, which is relevant because nicotine from smoking can activate these receptors, leading to increased tissue inflammation and vascular injury, thereby contributing to atherosclerosis and vascular aneurysm formation125.

However, an animal model study showed that stimulating the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) had positive effects against AAA126. This suggests that further research is needed to clarify the role of acetylcholine and its receptors in AAA pathogenesis. Tissue expression analysis revealed associations with pulmonary, alimentary, fibrous, and arterial tissues. These findings align with the gene-set enrichment results, indicating that pathways involved in nicotinic acetylcholine activation, lipid metabolism, and tissue remodeling play crucial roles in AAA pathogenesis. These terms are commonly linked to the lungs in relation to smoking, the gastrointestinal tract through lipid metabolism and nutrient absorption, and fibrous tissue in healing processes, reflecting dysregulation in aneurysmal vessels.

The AAA-associated PPI network was constructed using DEGs from TWAS and eQTL analyses, employing FUSION49 and FUMA, respectively. Degree and betweenness measurement were calculated to identify the key proteins. Ten key proteins, including PSMA4, CD40, PSMC3, LPR1, SCARA3, MRC2, PSRC1, ADAMTS7, FGF9, and MAP2K5, exhibited high scores in either degree or betweenness centrality. Among the prioritized proteins, CD40 and LPR1 demonstrated high scores in both degree and betweenness centrality. In the PPI network obtained from the STRING database, the interactions among these proteins have been validated through various experimental methods, such as yeast two-hybrid and co-immunoprecipitation, as well as through computational predictions based on gene co-expression, gene fusion, and neighborhood analysis. Additionally, evidence was gathered from curated databases and text mining of published literature51. The confidence in each interaction is indicated by the combined score, which reflects the number of methods supporting that interaction. These combined scores play an important role during centrality measurement for prioritizing important nodes. For example, nodes involved in interactions with high combined scores often form well-defined structures within the network, such as exhibiting high degree and bridging properties. Subsequently, these nodes also receive high rankings during prioritization, supporting their essential role in maintaining the function of the interaction network under disease conditions, as further validated by the combined score. Important nodes arise from the application of graph theory to the construction of biological networks, such as protein-protein interaction networks, gene co-expression networks, metabolic networks, and brain connectomes127. The first application of graph theory was in transportation problems, where it was used to identify optimal points or stations and the shortest paths to deliver mail or parcels more efficiently128. This concept is applied to biological phenomena, where the system transmits various biological signals through protein interaction networks to trigger specific biological processes or disease states129. Therefore, identifying important nodes or key genes within biological networks could play a crucial role in the investigation of disease-related genes.

We also compared our identified important nodes to other studies related to network analysis in AAA. In the PPI network analysis, we cannot experimentally validate the important nodes directly as the key node identification originates from graph theory and network science concepts. However, we validated indirectly by comparing our identified key nodes with other studies that identified these nodes based on PPI networks constructed from their own AAA transcriptomic experiments. Three important nodes from our PPI network, such as CD40, LRP1, and MAP2K5, have been previously reported in several AAA-related network analyses. Although CD40 was not clearly identified as an important node in any prior studies, two transcriptomic analyses of AAA reported that its ligand, CD40L, was upregulated under disease conditions130,131, suggesting its important roles in AAA pathology. A weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) study using three AAA transcriptomic datasets also identified LPR1 as a DEG with overlapping with previous GWAS studies132. Additionally, the same study reported that MAPKs acted as hub genes in two WGCNA-derived modules. These findings support the consistency of our constructed PPI network and prioritized important nodes with existing literature.

The association between our important nodes and AAA was also discussed. PSA4 inhibition was related to a decreased risk in aortic aneurysm from a Mendelian randomization study133. A GWAS meta-analysis demonstrated the association between a PSRC1 variant (rs602633) and AAA118. Despite no study in association between PSM3 and AAA pathology, its variants can cause aortic tissue injuries from proteotoxic stress due to proteasome dysfunction134. SCARA3 plays a vital role in oxidative stress protection135. Currently, there is no well-established evidence linking SCARA3 to the development of AAA. Its dysfunction may be associated with aortic injury due to uncontrolled oxidative stress. MRC2 has a function involving collagen fibrosis and remodeling136,137. Collagen dysregulation is one of the causes of aortic tissue pathology, leading to aneurysm. ADAMTS7, a metalloproteinase (MMP), has a role in collagen and extracellular matrix degradation. Dysregulation of metalloproteinases contributes to AAA development138. FGF9 signaling through PDGFRβ and ERK1/2 pathways results in AAA formation and progression139. The association between MAP2K5 is required for additional studies although its cascade (JNK) is related to the progression of AAA and intracranial aneurysm140,141.

LRP1 and CD40 were selected for molecular docking based on their consistently high scores in both high degree and betweenness centrality. The selection of these nodes was based on network biology principles, wherein key nodes are identified by their influence on the network structure and the transmission of information within the network129. In biological network analysis, centrality measures, which assess the importance of nodes within a graph or network, are commonly used to identify important nodes127. Several centralities have been developed to identify the importance of nodes in a network such as degree, closeness, betweenness, closeness, PageRank, and eigenvector centrality. However, many biological network analysis studies commonly prefer the use of degree and betweenness centrality measures142,143,144. These two methods are commonly used to identify important nodes in biological networks, as their centrality concepts reflect the functional significance of biomolecules within biological pathways. For example, degree centrality measures the number of direct interactions a node has with its neighboring nodes, analogous to identifying biomolecules that interact extensively with other molecular complexes. A node with a high degree is often considered crucial, as it may play a central role within molecular complexes or biological processes. Additionally, betweenness centrality evaluates the extent to which a node acts as a bridge or bottleneck in the transmission of information across the network145. This property is analogous to identifying key genes or proteins involved in signaling pathways. Nodes with both high degree and betweenness centrality scores are likely to play critical roles in maintaining the structure of the PPI network and facilitating biological information flow in AAA condition.

For LRP1 and CD40 prioritized from both degree and betweenness centrality with high score, we reviewed additional literature related to experiment studies. Although we could not directly validate their importance, as their prioritization was primarily based on graph theory and computational network biology concepts, we supported their relevance through evidence of their biological roles in AAA development and progression from several experimental studies. LRP1, a type 1 transmembrane receptor expressed ubiquitously146, plays a crucial role in vascular homeostasis by modulating vasoactive substances and intracellular signaling pathways147,148. Two primary binding sites (CR56 and CR17 subunits) on LRP1 interact with various molecules, including receptor-associated protein149,150, apolipoprotein E68, the synthetic peptide angiopep-2151, and potential anti-tumor drug candidates152. LRP1 also has protective effects on AAA development. Reduced LRP1 expression on monocytes with a pro-inflammatory profile is associated with atherosclerosis development153 and calcium signaling, which provides protection against aneurysm formation154. In addition, LRP1 also regulates MMP9 which is a key in AAA development via extracellular degradation155. A study from mouse embryonic fibroblast culture provided that LRP1 was a regulator in MMP9 level156. LRP1 also influences vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) migration and proliferation including vascular wall integrity147,155,157. VSMC dynamic disturbance leads to AAA formation. Several studies in mice models have revealed that smooth muscle depletion of LRP1 (smLRP1−/−) mice causes elastic layer disruption, aneurysm formation, and atherosclerosis148,158,159,160. The LRP1-deficient mice exhibit a proliferative VSMC phenotype and disrupted calcium signaling, impairing VSMC contraction and promoting aneurysm susceptibility. Additionally, downregulation of LRP1 in VSMCs impairs pericellular MMP-9 clearance, leading to extracellular matrix degradation and weakening of the vascular wall161. Genetic studies have also identified SNPs in LRP1 associated with increased risk of acute aortic dissection162.

CD40 interacts with CD40L, a key interaction in immune synapse stimulation. CD40L activation of CD40 triggers dendritic cells to activate antigen-specific T cells, which are essential for immune cell regulation and homeostasis163. The small molecule inhibitor BIO8898 disrupts the CD40L trimeric structure, representing a novel mechanism for PPI inhibitors65,164. CD40L deficiency has been shown to protect against dissecting aneurysms and reduce the risk of fatal rupture by decreasing inflammatory cell accumulation, activation, and protease activity in the arterial wall165,166. Several animal experiments have found that inhibiting CD40 signaling has a protective role in AAA progression. Soluble CD40L (sCD40L) levels were found to be significantly elevated in the luminal thrombus layer of AAA patients compared to other layers167. One study showed that angiotensin II-infused Cd40l−/− Apoe−/− mice had a significantly lower rate of AAA formation than angiotensin II-infused Apoe−/− mice130. The CD40L-deficient mice are protected from dissecting aneurysm formation and demonstrate a significantly lower incidence of fatal rupture, attributed to reduced infiltration and activation of inflammatory cells, as well as decreased MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity130. Another study revealed that induced C57BL/6 J mice with infrarenal aortic porcine pancreatic elastase infusion and inhibiting CD40 signaling with TRAF-STOP reduced aortic remodeling and diameter, and AAA development168. Moreover, human transcriptomic analysis from the same study revealed significant upregulation of CD40 and CD40L in AAA patient samples compared to control samples. In another study, a gradual increase in CD40L serum levels was observed in AAA model mice, correlating with progressive aortic dilatation169. Furthermore, in atherosclerosis, inhibition of CD40-CD40L signaling reduces plaque size and promotes a more stable, fibrotic plaque phenotype with lower inflammation170,171,172,173,174. This signaling pathway has similarly been explored in AAA. For instance, the antiplatelet drug trapidil, which inhibits CD40-CD40L interactions, reduced MMP-2 but not MMP-9 activity in human AAA tissue175. Currently, no pharmacological treatments are available for AAA; surgical intervention remains the only therapeutic option once the aneurysm exceeds 5.5 cm or becomes symptomatic. The accumulated experimental evidence supports a key role for CD40 and LRP1 in AAA pathophysiology, indicating that these molecules could serve as potential therapeutic targets. Further research into these pathways may offer promising strategies for the prevention or attenuation of AAA progression.

Drug repurposing was then performed for the two key proteins by searching for potential drug-gene or protein interactions in five databases: DrugBank57, TTD58, CTD59, GeneCards60, and STITCH v5.061. Several drugs targeting the two critical proteins, CD40 and LRP1, were identified from databases. For CD40, these include atorvastatin, clobetasol, gemcitabine, simvastatin, paclitaxel, and fludarabine, as well as anti-CD40 antibodies such as ruplizumab, rituximab, and abciximab. For LRP1, the identified drugs include cimetidine, ivermectin, triprolidine, tenecteplase, lanoteplase, lonoctocog alfa, and moroctocog alfa. Nevertheless, certain challenges were encountered: the three-dimensional (3D) structures of ruplizumab, tenecteplase, lonoctocog alfa, and moroctocog alfa were unavailable, and lanoteplase lacked complete annotation. These limitations hindered the investigation of their binding interactions with CD40 and LRP1. To overcome these challenges, the 3D structures of the targeted proteins can be predicted using AlphaFold2 software based on protein sequences176. Molecular docking studies demonstrated that most repurposed drugs, including both small molecules and antibodies, interacted effectively with CD40/CD40L and the CR56/CR17 subunits of LRP1, exhibiting varying binding affinities. These results suggest that the proposed framework for drug repurposing is an effective strategy, particularly in adapting to evolving disease conditions.

Currently, no small-molecule drugs specifically targeting the CD40-CD40L or LRP1 interactions have received FDA approval for routine clinical use. However, we compared the binding interactions of our candidate compounds with those of previously reported compounds from experimental studies, utilizing their 3D crystal structures obtained from the PDB62, to evaluate their interactions with the targeted proteins. Two potent anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies are in phase 2 clinical development. Bleselumab is designed to inhibit the CD40-CD154 interaction, thereby modulating immune responses associated with graft rejection177,178. On the other hand, dacetuzumab is being investigated for the treatment of CD40-positive malignancies, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and other hematologic malignancies179,180. In comparison to our candidate repurposed drug, abciximab, demonstrated stronger binding energy than both previously reported anti-CD40 agents. Furthermore, two agents targeting CD40L have also shown potential: suramin164,181, a polyaromatic compound that disrupts the trimeric structure of CD40L, and BIO889865, which intercalates between CD40L subunits, destabilizing its trimeric conformation and preventing CD40 binding. However, both compounds revealed weaker binding energies compared to our potent candidate, paclitaxel. In the case of LRP1 (CR56 subunit), the RAP has been instrumental in elucidating LRP1’s role in pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in mediating tau protein uptake and propagation182,183. Notably, RAP showed considerably poorer binding affinity toward LRP1 compared to our most promising candidate, Ivermectin. Although most of our candidate compounds displayed higher binding affinities and potential inhibitory efficacy than previously reported agents, additional experimental analysis is needed to further validate the efficacy of these candidates in subsequent investigations.

Several murine models have demonstrated that antiplatelet therapy exerts a beneficial effect on the development and progression of AAA167,184,185,186. Abciximab, a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, has been shown to reduce thrombus size and prevent aortic dilation in a rat xenograft model of aneurysm formation167. This antiplatelet agent suppresses P-selectin expression, decreases leukocyte adhesion to the luminal thrombus, limits medial elastin degradation, and promotes vascular smooth muscle cell attachment to the thrombus167. These findings emphasize a pivotal role of platelet activation in disease initiation, thrombus growth and remodeling, and the progression of AAA in this rat model. However, as abciximab is limited to parenteral administration, its clinical application in outpatient settings remains impractical. This limitation highlights the need for further research into the development of orally administered antiplatelet therapies.

Paclitaxel is a chemotherapeutic agent widely used in the treatment of various malignancies187,188,189. Importantly, paclitaxel-coated balloon (DCB) angioplasty was initially investigated for the treatment of de novo stenotic lesions in the femoral and popliteal arteries190,191,192,193. Cumulative evidence suggests that paclitaxel DCB angioplasty enhances vessel patency rates; however, the outcomes remain suboptimal194,195,196,197,198,199. A woven vascular stent-graft modified with silk fibroin-based microspheres containing paclitaxel, metformin, and methanol (SF-PTX-MET-MT microspheres) has been developed to provide sustained drug release, effectively inhibiting thrombosis and the progression of AAA200. The safety and efficacy of the drug-eluting stent were validated using a human umbilical vein endothelial cell line.

Ivermectin, a widely used antiparasitic agent in both humans and animals201,202, is also recognized as a classical selective inhibitor of the importin α/β nuclear transport pathway203. Despite no study of ivermectin in AAA, it has been shown to attenuate inflammatory responses by suppressing several key inflammation-related transcription factors, including NF-κB, NFAT1, AP-1, and STAT1204,205. Notably, ivermectin inhibits the nuclear translocation of NF-κB/p65 and downregulates the expression of major proinflammatory cytokines in mouse models of coxsackievirus B3-induced myocarditis and experimental autoimmune myocarditis206. These therapeutic effects observed in both viral and non-viral myocarditis models highlight Ivermectin’s potential as a candidate for the treatment of acute myocarditis206.

Conclusions

This study utilized an integrative bioinformatics approach, incorporating meta-analysis, functional enrichment analysis, network biology, and gene prioritization to analyze GWAS summary statistics from diverse study cohorts. Additionally, drug repurposing and molecular docking were performed to identify potential therapeutic candidates targeting key proteins. Our finding revealed novel significant SNPs and previously unreported disease-associated genes. Functional enrichment analysis highlighted key pathways, including lipid and cholesterol metabolism, tissue remodeling, and acetylcholine receptor activation. Furthermore, DEGs from eQTL and TWAS analyses were utilized to construct an AAA-related PPI network, prioritize critical proteins, and explore potential drug interactions. Overall, this study demonstrates the power of integrative frameworks in advancing the understanding of AAA pathogenesis and potential therapeutic strategies. These insights provide a valuable foundation for future investigations, encouraging further exploration through experimental validation and complementary computational approaches.

Data availability

The results of METAL summary statistics, TWAS, FUMA, PPI network analysis, drug repurposing, and molecular docking are available in the supplementary data.

Code availability

The source code for the GWAS meta-analysis, TWAS analysis, PPI network analysis, and figure plotting is available on GitHub (https://github.com/AugustusKH/AAA-MetaGWAS-FunctionalAnalysis). Additionally, all parameters used in FUMA and the HDOCK server are also provided in the GitHub repository.

References

Roth, G. et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 392, 1736–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32203-7 (2018).

Wei, L. et al. Global burden of aortic aneurysm and attributable risk factors from 1990 to 2017. Glob. Heart 16, 35. https://doi.org/10.5334/gh.920 (2021).

Koç, M. A. et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening: A pilot study in Turkey. Ulus Travma Acil. Cerrahi Derg. 27, 17–21. https://doi.org/10.14744/tjtes.2020.89342 (2021).

Lederle, F. A. The last (Randomized) word on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms. JAMA Intern. Med. 176, 1767–1768. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6663 (2016).

Guirguis-Blake, J. M., Beil, T. L., Senger, C. A. & Coppola, E. L. Primary care screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US preventive services task force. JAMA 322, 2219–2238. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.17021 (2019).

Wanhainen, A. et al. Editor’s choice - European society for vascular surgery (ESVS) 2019 clinical practice guidelines on the management of abdominal Aorto-iliac artery aneurysms. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 57, 8–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2018.09.020 (2019).

Kent, K. C. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 2101–2108. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1401430 (2014).

Sakalihasan, N. et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 34. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0030-7 (2018).

Vardulaki, K. A. et al. Quantifying the risks of hypertension, age, sex and smoking in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br. J. Surg. 87, 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01353.x (2000).

Kent, K. C. et al. Analysis of risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm in a cohort of more than 3 million individuals. J. Vasc. Surg. 52, 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2010.05.090 (2010).

Earnshaw, J. J. & Lees, T. Update on screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 54, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2017.04.002 (2017).

O’Donnell, T. F. X., Landon, B. E. & Schermerhorn, M. L. AAA screening should be expanded. Circulation 140, 889–890. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041116 (2019).

Wanhainen, A., Mani, K. & Golledge, J. Surrogate markers of abdominal aortic aneurysm progression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 36, 236–244. https://doi.org/10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306538 (2016).

Kent, K. C. Clinical practice. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 2101–2108. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1401430 (2014).

Thompson, A. R., Drenos, F., Hafez, H. & Humphries, S. E. Candidate gene association studies in abdominal aortic aneurysm disease: a review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 35, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.07.022 (2008).

Gibson, G. Hints of hidden heritability in GWAS. Nat. Genet. 42, 558–560. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng0710-558 (2010).

Gretarsdottir, S. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a sequence variant within the DAB2IP gene conferring susceptibility to abdominal aortic aneurysm. Nat. Genet. 42, 692–697. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.622 (2010).

Bown, M. J. et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm is associated with a variant in low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.002 (2011).

Bradley, D. T. et al. A variant in LDLR is associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 6, 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1161/circgenetics.113.000165 (2013).

Jones, G. T. et al. A sequence variant associated with sortilin-1 (SORT1) on 1p13.3 is independently associated with abdominal aortic aneurysm. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 2941–2947. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddt141 (2013).

Harrison, S. C. et al. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur. Heart J. 34, 3707–3716. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs354 (2013).

Ashvetiya, T. et al. Identification of novel genetic susceptibility loci for thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms via genome-wide association study using the UK Biobank Cohort. PLoS ONE 16, e0247287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247287 (2021).

Helgadottir, A. et al. The same sequence variant on 9p21 associates with myocardial infarction, abdominal aortic aneurysm and intracranial aneurysm. Nat. Genet. 40, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.72 (2008).

Gallagher, M. D. & Chen-Plotkin, A. S. The Post-GWAS era: From association to function. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 102, 717–730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.04.002 (2018).

Jones, G. T. et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for abdominal aortic aneurysm identifies four new disease-specific risk loci. Circ. Res. 120, 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.308765 (2017).

Klarin, D. et al. Genetic architecture of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the million veteran program. Circulation 142, 1633–1646. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.120.047544 (2020).

McGovern, D. P., Kugathasan, S. & Cho, J. H. Genetics of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 149, 1163-1176.e1162. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.001 (2015).

Mai, J., Lu, M., Gao, Q., Zeng, J. & Xiao, J. Transcriptome-wide association studies: recent advances in methods, applications and available databases. Commun. Biol. 6, 899. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-05279-y (2023).

Watanabe, K., Taskesen, E., van Bochoven, A. & Posthuma, D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat. Commun. 8, 1826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01261-5 (2017).

Barabási, A.-L. & Oltvai, Z. N. Network biology: understanding the cell’s functional organization. Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg1272 (2004).

Browne, F., Wang, H. & Zheng, H. A computational framework for the prioritization of disease-gene candidates. BMC Genomics https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-16-s9-s2 (2015).

Ozgür, A., Vu, T., Erkan, G. & Radev, D. R. Identifying gene-disease associations using centrality on a literature mined gene-interaction network. Bioinformatics 24, i277-285. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btn182 (2008).

Kumar, N. & Mukhtar, M. S. Ranking plant network nodes based on their centrality measures. Entropy https://doi.org/10.3390/e25040676.676 (2023).

Pushpakom, S. et al. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 18, 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd.2018.168 (2019).

Agu, P. C. et al. Molecular docking as a tool for the discovery of molecular targets of nutraceuticals in diseases management. Sci. Rep. 13, 13398. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-40160-2 (2023).

Sollis, E. et al. The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog: knowledgebase and deposition resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D977–D985. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac1010 (2022).

Zhou, W. et al. Global biobank meta-analysis initiative: Powering genetic discovery across human disease. Cell Genomics 2, 100192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xgen.2022.100192 (2022).

Backman, J. D. et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature 599, 628–634. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04103-z (2021).

Jiang, L., Zheng, Z., Fang, H. & Yang, J. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat. Genet. 53, 1616–1621. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00954-4 (2021).

Moore, C. M., Jacobson, S. A. & Fingerlin, T. E. Power and sample size calculations for genetic association studies in the presence of genetic model misspecification. Hum. Hered. 84, 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1159/000508558 (2020).

Patron, J., Serra-Cayuela, A., Han, B., Li, C. & Wishart, D. S. Assessing the performance of genome-wide association studies for predicting disease risk. PLoS ONE 14, e0220215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220215 (2019).

Kuhn, R. M., Haussler, D. & Kent, W. J. The UCSC genome browser and associated tools. Brief. Bioinform. 14, 144–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbs038 (2012).

Willer, C. J., Li, Y. & Abecasis, G. R. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics 26, 2190–2191. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340 (2010).

Armstrong, R. A. When to use the Bonferroni correction. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 34, 502–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12131 (2014).

Chen, Z., Boehnke, M., Wen, X. & Mukherjee, B. Revisiting the genome-wide significance threshold for common variant GWAS. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkaa056 (2021).

Turner, S. D. qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/005165 (2014).