Abstract

The current study mainly explores unsteady, laminar and mixed convection boundary layer flow of Casson ternary hybrid nanofluid in Dary-Forchheimer porous medium about a rotating sphere with slip velocity condition. The study considers quadratic thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model subjected to convective heating condition with entropy generation for efficient heat transfer and irreversible processes. The non-dimensional similarity variables are employed to convert the governing equations, nonlinear partial differential equations into nonlinear coupled ordinary differential equations. An implicit finite difference approach known, as Keller-box method numerically applied to solve the flow problem. The main findings for thermal and flow behavior of ternary hybrid nanofluid containing silver, titanium and alumina nanoparticles with blood as base fluid are presented through graphical and tabular forms. The outcomes depict that the magnetic field, inertia constant, unsteady and material parameter increases the velocity field, while angular velocity decreases. Moreover, the presence of thermal radiation and convective heat parameters highly optimize the thermal distributions of boundary layer, whereas the coefficient of heat transfer decreases. Conversely, thermal time relaxation and unsteadiness parameters lead to a decrease in temperature field and thermal boundary layer thickness for hybrid and ternary hybrid nanofluids. Entropy production reduces as magnetic parameter strengthen and increase with the Brinkmann number and convection parameter. The findings are confirmed a strong correlations with previous literature. Moreover, Response Surface Methodology and sensitivity analysis are established to quantify the effects of input parameters on thermal performance with values \(\hbox {R}^2\) = 99.99\(\%\), and \(\hbox {R}^2\)-adjusted = 99.98\(\%\), which confirm reliability of the result. The sensitivity analysis depicted that heat transfer rate is high sensitivity to heat generation, moderate sensitivity to nanoparticle volume fraction, and low sensitivity to radiation parameter with their maximum point 1.4178, 0.9898, and 0.4425, respectively. Further, ternary hybrid nanofluid reveals that greater heat transfer enhancement rate of \(1.44\%\) than heat transfer enhancement of hybrid nanofluid \(1.41\%\) at maximum value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optimizing the heat transfer rate in conventional fluids is a critical concern in various manufacturing industries and emerging nanotechnology. Numerous techniques have been introduced to enhance the thermal conductivity of base fluids in flow and heat transfer processes, as highlighted by Guedri et al.1. The suspension of solid nanoparticles within the base fluid has obtained substantial notice in heat transfer enhancement among various nanotechnologies, as nanoparticles exhibit unique properties such as a large surface area to volume ratio and high thermal conductivity. This accumulation of metallic or non-metallic nanoparticles to the conventional fluid results a novel class of fluids known as nanofluids, which was first introduced by Choi and Eastman2. Nanofluids demonstrate enhanced heat transfer capabilities due to the improved thermal properties of solid nanoparticles. Many scientists have considerably interested in nanofluids research because of its diverse potential applications in modern science and technology, including automotive cooling, aerospace engineering, heat exchangers, cooling of electronic devices, textiles, material processing, cancer therapy, drug delivery, energy storage, solar collectors, water distillation, temperature control systems, and various environmental applications3,4,5. Mahmood et al.6 have investigated the boundary layer behavior of Casson nanofluids and heat transfer using a non-Fourier heat model and entropy generation under thermal radiation and magnetic effects over permeable stretching surfaces. The results indicated that the Lorentz force enhances the temperature field while reducing the fluid motion within the thermal boundary layer. Numerous studies have explored the behavior of nanofluids across different fluid types and flow conditions7,8,9,10.

Now days, an enhancement in the thermal transfer rate of base fluid is the most important difficulties in many advanced industries and nanotechnologies. In this context, the dispersion of two nanoparticles into the convectional fluid gives rise to hybrid nanofluids, according to Nasir et al.11. Due to their remarkable thermal conductivity and other thermophysical properties, hybrid nanofluids demonstrate superior thermal performance and heat transfer rates compared to base fluids and nanofluids. Maskeen et al.12 studied energy transfer in alumina-copper/water based hybrid nanofluid under viscous dissipation, magnetic field, and thermal radiation effects over an elastic cylinder. In addition, the flow of hybrid nanofluid and thermal transfer in a Darcy Porous medium with chemical reactions through stretching surface were numerically investigated by Abd-Elmonem et al.13. Moreover, the ternary hybrid nanofluid is currently emerged through amalgamation of three different nanopraticles within the base fluid as novel types of nanofluids. Ternary hybrid nanofluids have optimized thermal properties, higher stability, and enhanced physical strength than hybrid and ordinary nanofluids Yang et al.14. An increasing number of researchers from diverse fields of study have investigating ternary hybrid nanofluid under different flow and heat transfer system due to enhanced thermal and heat transfer properties, which open new opportunities for various engineering and industrial applications as explored in15,16,17.

For example, The boundary layer flow of water-based ternary hybrid nanofluid with non-Fourier heat flux and activation energy past a stretching curve under convective heating is investigated by Sarada et al.18. Sajid et al.19 also analyzed the flow of a radiative Casson trihybrid nanofluid with heat generation using the Yamada-Ota and Xue nanofluid models under the effect of viscous dissipation in a porous rotating disk. Riaz et al.20 explored thermal transfer of non-Newtonian magnetized Williamson ternary hybrid nanoparticles (\(Al_2O_3, MgO, TiO_2\)) in a permeable stretching sheet under thermal radiation effect. Alwawi et al. The study of mixed convection flow and heat performance of magnetized trihybrid micropolar nanofluid in moving cylinder with constant heat flux using the Tiwari and Das model was analyzed by Alwawi et al.21. Further, Sharma et al.22 have conducted thermal radiation and entropy generation with homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions in blood-based ternary hybrid micropolar nanofluid flow using the Bayesian regularization network algorithm. Moreover, the behavior of flow and thermal transfer of non-newtonian MHD ternary hybrid nanofluid over nonlinear stretching surface has been discussed by Naidu et al.23.

The study of non-Newtonian fluids and energy transfer has significant attention in recent years due to their wide-ranging applications in industries such as food processing, water pollution control, material production, pharmaceuticals, biochemical systems, cooling of nuclear reactors, and molten polymer processing. One of the notable and realistic types of non-Newtonian fluid models that possesses shear-thinning properties and yield stress is Casson fluid, which was coined by Casson24. The Casson fluid model is widely applied in various fields, including biomechanics and industrial processes, with materials like blood, chocolate, fruit juices, ice cream, jelly, and honey being prominent examples. Jamshed et al.25 examined unsteady non-Newtonian Casson nanofluid flow and energy transfer over a stretching surface with entropy analysis, considering the effects of thermal convection and slip constraints. The effects of Newtonian heating and thermal radiation on convective MHD non-Newtonian Casson fluid flow through porous plate has been numerically studied by26,27. In addition, Sademaki et al.28 have investigated unsteady hydro-magnetic convection flow of non-Newtonian Casson with heat source in a porous medium. Porous medium is another crucial mechanism in strengthen thermal efficiency of the flow system Sankari et al.29. The flow non-Newtonian Casson ternary hybrid nanofluid with thermal tranfer across Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium in the presence of thermal radiation and magnetic field under slip and melting heat condition has been discussed in30,31,32. Babu et al.33 have examined natural convection flow ternary hybrid nanofluid with joule heating saturated in Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium. Moreover, Khan et al.34 investigated entropy generation analysis on electromagnetic flow of micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with porous Darcy-Forchheimer medium subjected to electromagnetic and thermal radiation effects.

Thermal radiation, a form of electromagnetic radiation, plays a crucial role in heat transfer and is detected as the thermal flow of particles. It is particularly important in various medical and engineering applications, such as nuclear fusion, heat energy utilization, polymer processing, power plants, solar energy systems, gas turbines, cancer treatment (e.g., chemotherapy), space vehicles, aircraft, satellites, and missiles Mohanty et al.35. Jamshed and Aziz36 examined electrically conducting non-Newtonian Casson hybrid nanofluid with radiation and entropy generation over an extended sheet using the Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model. The analysis of thermal radiation with entropy generation for MHD nanofluid flow over stretched surface under slip and convective conditions were explored in37,38,39,40. Rehman et al.41 explored the Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model with Darcy-Forchheimer and radiation effects on Sutterby nanofluid flow over a stretching surface. Noreen et al.42 analyzed MHD flow of ternary hybrid nanofluids over a double rotating disk with thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux effects. Quadratic and nonlinear thermal radiation have recently become active research areas due to their essential applications in heat transfer phenomena. Ali et al.43 studied the unsteady viscoelastic Casson ternary hybrid nanofluid flow and heat transfer in porous media over a nonlinear stretching disk under the influence of magnetic field and thermal radiation.

The impact of magnetic fields on energy transfer in electrically conducting fluids has gained significant interest in various industrial and engineering applications, including reactor cooling, molten metal purification, electricity generation, glass production, metal coating, and chemical engineering according to44,45. Usman et al.46 examined the mass and energy transfer characteristics of non-Newtonian Casson couple stress hybrid nanofluids around a spinning disk under the influence of electric and magnetic fields. Hussain et al.47 studied electrically conducting magnetized Casson hybrid nanofluids and thermal analysis with stagnation point flow under the effects of thermal radiation. Jakeer et al.48 investigated heat transfer in Darcy-Forchheimer flow of electrically magnetized hydrodynamic couple stress CuCNT-Ti/water-based ternary hybrid nanofluids under uniform heat source/sink and radiation effects. Gupta et al.49 explored heat and mass transfer with the Cattaneo-Christov model in thermally radiative EMHD hybrid nanofluids over a bidirectional extended stretching surface.

In recent years, the flow problem over a rotating sphere has attracted the attention of numerous researchers due to its extensive applications in advanced industrial and engineering fields, including the food industry, fiber coating, chemical processing, floating bodies in water, rotating machinery, thermal power plants, meteorology, and hydraulic transport according to Lone et al.50. Mahdy and Ahmed51 examined convection stagnation point flow of Casson nanofluid over an impulsively rotating sphere under the influence of a magnetic field. Mahdy et al.52 also discussed the non-Newtonian Casson nanofluid flow in the existence of entropy generation analysis in the stagnation region over a rotating sphere. The study assumed the effects of magnetic field with mixed convection under convective bounder condition. Ali et al.53 analyzed thermal flow of bio convective tangent hyperbolic nanofluid in the stagnation point of a cycling sphere along with buoyancy force and magnetic field effects using finite element analysis. Additionally, unsteady mixed convection flow of couple stress hybrid nanofluid about a rotating sphere towards stagnation region using HAM has been analyzed by Gul et al.54. The study significantly elaborate the influence of magnetic field with thermophoresis and Brownian motion under convective boundary condition. Furthermore, Gamachu et al.55 have investigated mixed nonlinear convection with unsteady electro-hydromagnetic flow of Sutterby hybrid nanofluid in the stagnation zone of a spinning sphere under the effects of thermal radiation .

A comprehensive studies in the literature have mainly investigated to discuss the flow and thermal transfer properties under different conditions including magnetic field, mixed convection, non-Newtonian fluid behavior, nanofluid, and, hybrid nanofluid. However, an electrically conducting EMHD Casson ternary hybrid nanofluid flow in a porous medium around spinning sphere incorporated with non-Fourier heat flux model and thermal radiation has not yet been discussed. Build upon this gap, the present study specifically extends to investigate the unsteady EMHD Casson non-Newtonian ternary hybrid nanofluid flow in Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium with quadratic thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model around a rotating sphere. The ternary hybrid nanofluid is obtained by composition of silver (Ag), titanium dioxide \((TiO_2)\), and aluminum oxide \((Al_2O_3)\) nanoparticles in blood as based fluid. This innovative use of ternary hybrid nanofluid is a novel contribution to the existing body of literature with unique combinations of factors including Casson non-Newtonian fluid, electromagnetic field, Dary-Forcheimer porous medium, nonlinear Boussinesq approximation, joule heating, heat generation, and convective boundary condition. Moreover, the inclusion of the Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model with quadratic thermal radiation offers further precision of heat transfer processes, accounting for finite heat propagation and complex heat flux behaviors. Additionally, the Darcy-Forchheimer theory is considered to examine the impact of both inertial and porous drag.

The current model provide a more accurate and notable advancement to the flow and heat transfer within the system, enhancing the efficiency and reliability of the obtained results. The governing equations are transformed from nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs) into ordinary differential equations (ODEs) using appropriate non-dimensional variables. The resulting system is then solved numerically using the Keller Box method via MATLAB R2023a. Furthermore, response surface methodology (RSM) is employed with sensitivity analysis to statistically examine the effects of input parameters on heat transfer rate. The findings of this study has potential applications in various fields including biomedical engineering, cooling and heating electronic device, cancer treatment, drug delivery, transportation, and industrial processes.

Problem formulation and assumptions

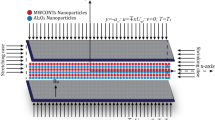

This study investigate the unsteady, incompressible and laminar flow of an electrically conducting magnetohydrodynamic ternary hybrid Casson nanofluid subject to mixed nonlinear convection in a Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium. The problem is motivated by the need for improved thermal management and enhancement in advanced fluid flow system, with applications in industrial processes, energy systems, and biomedical devices. The ternary hybrid nanofluid is accounted for three distinct solid nanoparticles including silver (Ag), titanium dioxide \((TiO_2)\), and aluminum oxide \((Al_2O_3)\) suspended in a Casson base fluid, influenced by time-dependent external electric and magnetic fields, impacting both flow dynamics and heat transfer. The thermophysical properties of nanoparticles and base fluid is given in Tables 1 and 2.

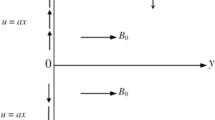

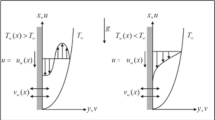

Quadratic thermal radiation is modeled using the Rosseland approximation to capture significant temperature variations, while the non-Fourier heat conduction is represented by the Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model. The fluid flow and heat transfer are examined for a rotating sphere with a radius r(x), driven by an angular velocity \(\textbf{S}(t)=Bt^{-1}\) along the diameter, parallel to the free stream velocity \(u_e=Axt^{-1}\), where A and B are positive constants, and \(t>0\). The coordinates are aligned with the surface of the sphere (x-axis), perpendicular to the surface (y-axis), and in the spinning direction (z-axis). The electric field and magnetic field are implemented orthogonal to the flow direction to consider the Lorentz force effects, which is a resistance force used to control the flow of nanofluid in the opposite direction. The effects of Darcy-Forchheimer drag in the porous medium add complexity to the flow due to viscous and inertial resistance. Additionally, the analysis incorporates heat enhancement rate and entropy generation, providing insights into energy efficiency and irreversibility in the flow system. Buoyancy forces due to thermal expansion with convective heat and slip effects at the surface are also considered for a comprehensive understanding of the fluid and thermal dynamics.

This research aims to:

-

1.

Analyze the impact of quadratic thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat conduction on the heat transfer performance of a ternary hybrid nanofluid.

-

2.

Investigate the effects of magnetic field, electric field, Darcy–Forchheimer drag, velocity slip, and nonlinear convection on fluid flow and heat transfer enhancement.

-

3.

Assess entropy generation to gain insights into the system’s energy efficiency and irreversibility.

-

4.

Utilize Response Surface Methodology to analyze the sensitivity for optimizing and designing the characteristics of key parameters.

Governing equations

The governing equations of the flow problem are derived by the following partial differential equations for conservation of mass, momentum, and energy balance, combining the previously stated assumptions that follow the approaches of Usman et al.46, Lone et al.50, Gamachu et al.56, and Kenea et al.57. The schematic physical flow and geometric configuration is given in Fig. 1.

Where the initial and boundary constitutes are defined as:

where (u, v, w) denotes the components of velocities along x, y, and z axes, and t is time. In addition \(\beta\), g, \(B_0\), \(E_0\), \(k^p\), \(F_d\), \(Q_0\), \(\varepsilon _t\), \(h_f\), \(T_f\), T, \(T_{\infty }\) represents casson parameter, gravity of fluid, magnetic field strength, electric field, porous permeability, inertia coefficient, heat generation coefficient, thermal relaxation time, rate of heat transfer, reference temperature, temperature at surface and free stream condition accordingly. Also \(\rho _{thnf}\), \(\mu _{thnf}\), \(\sigma _{thnf}\), \(k_{thnf}\), \((\rho C_p)_{thnf}\), \((\beta _0)_{thnf}\), \((\beta _t)_{thnf}\) being density, viscosity, electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, linear and nonlinear thermal expansion coefficient of ternary hybrid nanofluid, respectively. By applying Rosseland approximation, the thermal radiation \(q_r\) can be described as58:

Where \(\sigma ^*\) and \(k^*\) being Stefan-Boltzmann and mean absorption rate. The quadratic thermal radiation is considered for sufficient temperature variations and the term \(T^4\) can be expanded around \(T_{\infty }\) using Taylor series and dropping higher-order terms we have59,60:

Now, using Eq. 7 the radiative heat flux can be represented by:

Therefore, substituting Eq. (9) into Eq. (4) yields

The similarity variables employed in the current problem are52,55,61:

Employing similarity conversion in Eq. (11), the mathematical equations in Eqs. (2–4) with boundary limit Eq. (5) are reduced into system of ODEs:

Subjected to the limit conditions

where

The skin friction coefficient and Nusselt number are specified in the form:

This physical measures can be transformed to:

Heat transfer enhancement

The enhancement of heat transfer in nanofluids is one of the primary motivations for their application in industrial and engineering systems. The suspension of nanoparticles in a base fluid leads to modifications in the thermal conductivity, viscosity, and convective heat transfer behavior of the fluid. These enhancements are particularly significant in boundary layer flows, where efficient heat dissipation is critical.

To quantify the impact of nanoparticle concentration on heat transfer performance, a widely used dimensionless metric is the “Heat Transfer Enhancement (HTE)”percentage. This quantity compares the normalized Nusselt number (a measure of convective heat transfer) in the presence and absence of nanoparticles.

Mathematically, the HTE can be expressed as65:

In this equation:

-

\(Nu_x\) is the local Nusselt number at a location x along the surface.

-

\(Re_x\) is the local Reynolds number based on the distance x.

-

\(\phi\) denotes the nanoparticle volume fraction.

-

\(\phi = 0\) corresponds to the case of a pure base fluid (no nanoparticles).

-

\(\phi \ne 0\) corresponds to the nanofluid case, i.e., when nanoparticles are present in the fluid.

The expression \(\frac{Nu_x}{\sqrt{Re_x}}\) is used as a normalized heat transfer rate to eliminate the effect of flow velocity and viscosity variations due to Reynolds number changes.

The HTE value gives the percentage increase (or decrease) in heat transfer due to the inclusion of nanoparticles. A positive HTE indicates enhancement, while a negative value would imply deterioration. This measure is essential for evaluating the thermal performance of nanofluids in practical heat transfer systems such as heat exchangers, solar collectors, and cooling channels.

Numerical studies, including the present work, demonstrate that increasing the nanoparticle concentration generally leads to an increase in \(Nu_x\), hence improving the HTE. However, this enhancement comes with trade-offs such as increased pressure drop and changes in flow structure, which must be considered in design and optimization.

Entropy generation

Entropy generation is a fundamental concept in thermodynamics that measures the irreversibility associated with real processes. In any thermal system, irreversibilities arise due to factors such as fluid friction, heat transfer across finite temperature differences, viscous dissipation, Joule heating, and mass diffusion. These mechanisms contribute to the degradation of useful energy, leading to entropy production.

In systems involving electrically conducting fluids under the influence of magnetic fields such as those encountered in magnetohydrodynamic flows, electro-hydrodynamic flows, and nanofluid applications the sources of entropy generation become more complex and significant. The magnetic field induces Lorentz forces, which result in additional joule heating, thereby amplifying the entropy production. Similarly, viscous dissipation becomes notable in boundary layer flows, especially when non-Newtonian or hybrid nanofluids are involved.

Minimizing entropy generation is a key objective in thermal system design, as it correlates directly with energy efficiency and performance.

In the present flow configuration,the entropy generation for the flow system can be expressed as60,66,67,68:

Now the rate of entropy generation can be described in the form

Here, \(Sg = \frac{k_f \nabla T}{\nu _f T_{\infty }}\) denotes entropy production rate. Now using Eq. (11) the dimensionless form of entropy generation becomes:

\(Br = \frac{\mu _{f}u_e^2}{k_f(T_f - T_{\infty })}\) represent Brinkman number. The Bejan number defined as entropy generation due to thermal system to total entropy generation. Mathematical expression of Bejan number can be written as

Numerical procedures

Due to the strongly coupled and nonlinear nature of the conservation equations in Eqs. (12–14) associated with limit condition Eq. (15), the flow problem is numerically solved using Keller-Box method. The method is effective and reliable for boundary layer flow problems, providing second-order convergence with an unconditionally stable solution69. The key steps involved in the Keller-Box method are as follows:

-

1.

Transformation of ODEs By establishing the new dependent variables u, v, w, t with \(u = f'\), \(v = u' = f''\), \(w = g'\), \(t = \theta '\), the governing equations Eqs. (12–14) with associated limit condition in Eq. (15) are transformed to the subsequent system of first-order.

$$\begin{aligned} \omega _1\omega _2(1+\frac{1}{\beta })v' + A fv + \frac{1}{2}(u + \frac{\eta }{2}v - 1) + \frac{A}{2} (1 - u^2 + \lambda g^2) - \omega _1\omega _2 \frac{A}{2}K_r(u - 1) \end{aligned}$$$$\begin{aligned} -\frac{A}{2}F_d(u^2 - 1) + \frac{A}{2}\gamma \omega _2(\omega _4\theta + \omega _5\gamma _1 \theta ^2) + \omega _3\omega _2 \frac{Ma}{2} (E_f - u + 1) = 0, \end{aligned}$$(25)$$\begin{aligned}&\omega _1\omega _2(1+\frac{1}{\beta })w' + A (fw -ug) + \frac{1}{2}(g + \frac{\eta }{2}w)- \omega _1\omega _2\frac{A}{2}K_rg - \frac{A}{2}\sqrt{\lambda }F_dg^2 \nonumber \\&+ \omega _3\omega _2\frac{Ma}{2}(\frac{1}{\sqrt{\lambda }}E_f - g) = 0, \end{aligned}$$(26)$$\begin{aligned}&\frac{1}{Pr}\omega _7 \omega _6 t' + \frac{\omega _7}{Pr}Nr (3\alpha (t^2 + \theta t') - 2t') + \frac{\eta }{4}t + A ft + \tau A(A f^2t' + A fut) \nonumber \\&+ \omega _7 \frac{A}{2}\varpi \theta + \omega _2 \omega _3 Ec \frac{Ma}{2} \left\{ (u - E_f)^2 + \lambda (g-E_f)^2 \right\} = 0, \end{aligned}$$(27)$$\begin{aligned}&f(0) = 0, \quad u(0) = \delta v(0), \quad g(0) = 1, \quad \omega _4 t(0) = -Bi(1-\theta (0)),\quad \text {at} \quad \eta = 0 \end{aligned}$$$$\begin{aligned} \quad u(\eta ) \rightarrow 1, \quad g(\eta ) \rightarrow 0, \quad \theta (\eta ) \rightarrow 0, \quad \text {for} \quad \eta \rightarrow \infty . \end{aligned}$$(28) -

2.

Discretization and difference equations A domain discretization and grid points of rectangular mesh in the \(x-\eta\) coordinates are characterized in Fig. 2 as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} x^{0}= 0, \quad&x^i = x^{i-1} + h_i, i = 1, 2, 3, \dots I, \\ \eta _0 = 0, \quad&\eta _j = \eta _{j-1}+ k_j, j = 1, 2, 3, \dots J, \hspace{0.1cm} \text {where} \hspace{0.1cm} h_i = \Delta x, \hspace{0.1cm} \text {and} \hspace{0.1cm} k_j = \Delta \eta \hspace{0.1cm} \text {are the} \hspace{0.1cm} \text {step size}. \end{aligned}$$Then, an algebraic equations are developed by utilizing central difference construction to the linear system of ODEs at the point (\(x^i, \eta _{j-\frac{1}{2}}\)).

-

3.

Block tri-diagonal matrix The structure of block tri-diagonal matrix has been utilized to the linearized system of equations as:

$$\begin{aligned} [\Lambda ][\delta ] = [\xi ] \end{aligned}$$(29)Where,

$$\begin{aligned}\small [\Lambda ] = \begin{bmatrix} [A_1] & [C_1] & & & & & \\ [B_2] & [A_2] & [C_2] & & & & \\ & & & \ddots & & & \\ & & & \ddots & & & \\ & & & \ddots & & & \\ & & & & [B_{J-1}] & [A_{J-1}] & [C_{J-1}] \\ & & & & & [B_J] & [A_J] \end{bmatrix}, [\delta ] = \begin{bmatrix} [\delta _1] \\ [\delta _2] \\ \vdots \\ [\delta _{J-1}] \\ [\delta _J] \end{bmatrix}, \text {and} \quad [\xi ] = \begin{bmatrix} [\xi _1] \\ [\xi _2] \\ \vdots \\ [\xi _{J-1}] \\ [\xi _J] \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}$$

Here \(\Lambda\) represents the \(7\times 7\) block sized matrix related with the generalized size of \(J \times J\). However, \(\delta\) and \(\xi\) denotes a column vectors of order \(J \times 1\). Further, an eminent LU decomposition technique has been used to obtain the solution for \(\delta\). That is, assuming \(\Lambda\) in Eq. (29) is non-singular and can be factorized into lower and upper trigonal matrices as:

Later the forward and backward update conditions are applied to end the solution. During this study, where \(\Delta \eta = 0.01\) is chosen as step size, the convergence condition was asymptotically fulfilled at the maximum point of \(10^{-5}\) after the series of estimations.

Validation of the numerical scheme

In this part, the legitimacy of the numerical scheme is evaluated by considering skin friction and heat transfer rate. The computational results obtained by present scheme are tremendous conformity with prior published results by Gul54, and Dinarvand70 as indicated in Table 3. This proves the validity of current numerical scheme.

Results and discussion

The characteristics of various flow fields in the problem, including linear and angular velocities, entropy generation, temperature distribution, and key engineering quantities such as the skin friction coefficient and heat transfer rate, have been thoroughly analyzed and presented through graphs and tables using MATLABR2023a. To perform this analysis, the numerical values of physical parameters were carefully chosen based on their relevance, historical significance, and uniqueness within the given context as \(0.1 \le Ma \le 0.5\), \(0.5 \le \beta \le 5\), \(0.5 \le K_r \le 5\), \(0.5 \le F_d \le 5\), \(0.1 \le A \le 0.5\), \(0.1 \le \lambda \le 0.5\), \(0.01 \le E_f \le 0.5\), \(0.1 \le \gamma \le 0.5\), \(0.5 \le \gamma _1 \le 2\), \(0.1 \le \varpi \le 5\), \(0.5 \le Nr \le 2\), \(0.1 \le \alpha \le 0.1\), \(5 \le Pr \le 15\), \(0.1 \le \tau \le 5\), \(0.5 \le Br \le 5\), \(0.1 \le \delta \le 0.5\), \(0.5 \le Bi \le 15\), \(0.01 \le \chi _1, \chi _2, \chi _3 \le 0.03\). The result shows significant improvements in velocity, temperature, and entropy profiles compared to the existing literature, due to the optimization of flow and heat transfer by ternary hybrid nanofluids. Additionally, the inclusion of thermal relaxation time and quadratic radiation further optimizes the thermal management system’s performance. Finally, Response Surface methodology is employed on the rate of heat transfer to predict the optimal parameter through ANOVA analysis.

Velocity distribution

The effects of various flow parameters on the linear and angular velocity fields are illustrated in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13. Figs. 3 and 4 present the behavior of linear and angular velocity in response to increasing values of the Casson parameter (\(\beta\)). The results indicate that strengthen Casson parameter leads to upgrade linear velocity and reduce angular velocity. Because for larger \(\beta\) parameter the casson fluids changes from non-Newtonian to Newtonian behavior due to lessen fluid plasticity, which causes higher linear velocity gradient but decreases angular velocity.

The magnetic parameter (Ma) has higher influence on the velocity profiles is shown in Figs. 5 and 6. The findings reveal that the linear velocity field is enhanced as a function of Ma. Conversely, angular velocity becomes reduced with greater magnitudes of Ma. This is due to the applied magnetic field induces a current in the conducting fluid and it can generates an electromagnetic force known as the Lorentz force, which acts normal to the flow of nanofluid. Therefore, as Ma increases the nanofluid velocity profile increases in the x-direction while a reducing angular velocity due the effects of magnetic field perpendicular to the surface.

The effect of the electric field constant on both linear and angular velocities is displayed in Figs. 7 and 8. The results show that both velocity profiles increase as the electric field strength increases. Physically, this means that a stronger electric parameter experiences greater force on the charged particles, increasing their linear acceleration and the rate of rotation along their trajectory. As result, both the linear velocity and angular velocity are enhanced. The impact of the unsteady parameter (A) on the linear and angular velocity profiles is depicted in Figs. 9 and 10. The outcomes reveal that the free stream velocity improves due to amplifying values of unsteadiness parameter as discussed in Fig. 9. Whereas it has been distinguished the angular velocity reflects a decreasing behavior as shown in Fig. 10. The actual justification is the nanofluid velocity profile is amplified at its free stream due to positive increment of a constant parameter (\(A > 0\)), which leads a redistribution of angular momentum in the boundary layer region. Consequently, the motion of velocity profile increase in the flow direction while slowing down in rotational axis near the boundary region.

The influence of the Forchheimer constant (\(F_d\)) on both linear and angular velocity profiles is discussed in Figs. 11 and 12, respectively. The results indicate that the linear velocity increases with higher Forchheimer factors, while the angular velocity shows a decreasing behavior. This justifies that when the Forchheimer number enlarges the inertial resistance to the rotational motion increase due to nonlinear effects but the linear motion is less sensitive to the Forchheimer drag. Hence, the ternary hybrid nanofluid velocity enhances in the stream wise direction while angular velocity decreases. Fig. 13 shows the fluctuation of linear velocity profile due to the escalating of the (\(\lambda\)) rotational parameter. The upshots depict that the augmentation in the rotational parameter intensifies the velocity of ternary hybrid nanofluid in the x-direction. This is because the frictional force rises with increasing the rotational parameter, which injects an extra momentum into the motion fluid within the boundary region. As a result, the velocity profile in the free stream enhanced for amplifying rotating parameter.

Temperature distribution

The distinct behavior of the temperature profile for various control parameter effects of hybrid nanofluid (\(Ag+TiO_2/blood\)) and ternary hybrid nanofluid (\(Ag+TiO_2+Al_2O_3/blood\)) explored in Figs. 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 20. Fig. 14 demonstrates the effects of the temperature gradient parameter (\(\alpha\)) on the thermal characteristics of ternary hybrid nanofluid. The graph reveals the temperature profile decreases as the temperature gradient ratio parameter increases. Practically, an increment in the temperature gradient parameter means the difference between surface and ambient temperatures grows larger relative to the ambient temperature, leading to a drop in the temperature profile.

The influence of unsteadiness parameter (A) on the temperature field of ternary hybrid nanofluid is reflected in Fig. 15. It can be seen that an increasing in the unsteady parameter causes a reduction in the temperature profile. Physically, this indicates increasing magnitudes of A causes to enhance natural instability in the boundary layer which can influence the temperature distribution, and therefore the temperature profiles and thermal boundary layer are breaking down to the surface. On the other hand, Fig. 16 reveals that the temperature distribution and thermal boundary layer increases with higher values of the radiation parameter (\(N_r\)). In physical justifications, stronger thermal radiation generates an extra heat near the surface in both (\(Ag+TiO_2/blood\)) and (\(Ag+TiO_2+Al_2O_3/blood\)) nanofluids, which can lead to improved cooling performance and thermal management efficiency.

Fig. 17 shows that the temperature distribution and thermal boundary layer are improved as the Biot number (Bi) increases. This is due to higher Bi values at the surface of the spinning sphere reduce thermal resistance, leading an improved temperature distribution and convective thermal transmission. Fig. 18 illustrates the impacts of thermal relaxation time parameter (\(\tau\)) on the characteristics of temperature distributions within the boundary domain. It is observed that the thermal boundary layer thinner as temperature profile reduces for ascending values of thermal relaxation time (\(\tau\)). In practical terms, increased thermal relaxation time (\(\tau\)) results faster temperature gradient dissipation and enhance heat transfer processes between the materials by reducing time to reach the desired thermal equilibrium. This results in more efficient and faster thermal management.

Fig. 19 explains the effects of the Prandtl number (Pr) on the ternary hybrid nanofluid temperature profile. It is clear that as the Prandtl number increases, the temperature profile declines. This occurs because a higher Prandtl number corresponds to lower fluid thermal conductivity, which reduces the temperature in both hybrid and ternary hybrid nanofluids.

In Fig. 20, the temperature profile decreases with increasing heat absorption parameter (\(\varpi\)). In practical applications, such as cooling systems for electronic devices or industrial processes, nanofluids help maintain a stable temperature despite high heat generation. Their ability to reduce the temperature field even under increased heat generation stems from their enhanced thermal properties and improved heat transfer mechanisms.

Entropy and Bejan number analysis

The effects of governing parameters such as magnetic field, rotation parameter, Brinkmann number, unsteadiness parameter, Casson parameter, radiation parameter, and electric field on entropy generation and the Bejan number are analyzed in Figs. 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 and 30. The behavior of entropy generation under the effects of the magnetic field strength is detailed in Fig. 21. It shows that the rate of entropy generation decline as the magnetic parameter (Ma) enhances. The magnetic parameter relates to the influence of a magnetic field on a fluid flow. Higher magnetic field strength generates a resistance force that tends to slow the flow of fluid due to low friction and dissipation systems, results in higher thermal control with lower entropy generation. Similar behavior is observed with increasing electric field values, as shown in Fig. 22.

Fig. 23 illustrates that the rate of entropy generation rises with higher Brinkmann number (Br). This is because increased viscous effects for larger Brinkmann numbers elevate the entropy generation rate in the boundary region. It is crucial in practical applications to reduce energy losses due viscous dissipation by optimizing thermal management systems. On the other hand, an inverse trend is seen in the Bejan number as the magnetic field and Brinkmann number increase, as shown in Figs. 24 and 25, respectively. This happens due to Bejan number represents the relative importance of thermal irreversibility compared to viscous irreversibility. An increase Bejan number revealed that thermal irreversibility are significant than fluid friction losses in the system as magnetic field reduces viscous dissipation.

The impact of the thermal radiation parameter (Nr) on entropy generation is shown in Fig. 26. As the radiation parameter increases, the entropy generation rate rises near the wall of the sphere but shows minimal variation further from the wall. In general, as thermal radiation increases, more heat is generated near the surface, creating higher temperature gradient and efficient energy transfer, resulting increased entropy. While farther from the wall, less thermal effects leading to reduced temperature gradient and decreased entropy generation. In Fig. 27, entropy generation is shown to increase with larger values of the rotational parameter (\(\lambda\)).

Fig. 28 depicts the response of entropy generation to changes in the casson parameter (\(\beta\)). As the Casson parameter increases, the rate of entropy generation decreases. This occurs because higher values of the Casson parameter cause the fluid to transition from non-Newtonian to Newtonian behavior, reducing entropy generation. Conversely, the Bejan number increases with the Casson parameter, as seen in Fig. 29. Since the total entropy generation decreases with higher Casson parameter values, the Bejan number rises due to the inverse relationship between these quantities.

Finally, the effect of the unsteadiness parameter on entropy production is shown in Fig. 30. Entropy generation increases close to the wall of the sphere but gradually decreases as one moves far from the wall, highlighting the localized effects of these parameters on the system.

Skin friction and Nusselt number

The influence of various control parameters on key physical quantities, such as skin friction drag and heat transfer rate, has been analyzed and is presented in Figs. 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 and 39. The results indicate that the coefficient of skin friction decreases with increasing material parameter (\(\beta\)) and unsteadiness parameter (A), while it rises with larger values of the magnetic parameter (Ma) and rotation parameter (\(\lambda\)), as discussed in Figs. 31, 32, 33 and 34. Which indicates that Ma, \(\lambda\) are directly related to skin friction and the higher rotational speed of sphere significant increase the skin friction at the surface.

Furthermore, Figs. 35, 36, 37, 38 and 39 illustrate the variations of heat transfer rate for different physical parameters. Figs. 36 and 37 demonstrate that higher values of the Biot parameter (Bi) and radiation parameter (Nr) lead to a reduction in the heat transfer coefficient. An increase in the thermal radiation the process of heat transfer near the surface becomes dominant, resulting in a reduced Nusselt number as it represents convective heat transfer. In addition, a greater Biot number indicates that enhancing the temperature gradient within the material leads to effective convective heat transfer at the surface, resulting in a reduced Nusselt number. Conversely, the coefficient of heat transfer is enhanced with increasing unsteadiness parameter (A), Prandtl number (Pr), and temperature gradient ratio (\(\alpha\)). A comparative evaluation of the current results confirms good agreement, as shown in Table 3. Moreover, the rate of energy transfer for enhancing concentration nanoparticle \(\chi\) is depicted through bar chart in Fig. 40. It is observed that the rate of heat transfer enhances for increasing percentage of nanoparticle volume fraction (\(0 \le \chi \le 1\)) having enhancement rate \(1.41\%\), and \(1.44\%\) at maximum level for hybrid and ternary hybrid nanoparticles, respectively. Which indicates that ternary hybrid nanofluid has superior heat transfer rate than hybrid nanofluid containing greater number of nanopraticles.

Response surface methodology

Response surface methodology is statistical approach used to construct model and analyze the relationship between the independent factors (inputs) and response variables (71,72,73). In the present study, the key elements of response surface method known as face central composite design is utilized to construct a quadratic model in order to investigate the relationship between independent variables (input) and the response in particular heat transfer rate (\(Nu_x\)). The computation particulary focus on the three parameters with predefined intervals of heat generation (\(0.3 \le \varpi \le 0.5\)), radiation parameter (\(2 \le Nr \le 4\)), and volume fraction (\(0.03 \le \phi \le 0.09\)). The factors of parameters along with their corresponding levels (-1, 0, 1) and coded symbols (\(\vartheta _1, \vartheta _2, \vartheta _3\)) are given in Table 4. An experimental simulation of 20 runs for three independent parameters with their corresponding coded levels is presented in Table 5. The quadratic model that describe the relationship between the response variable and parameters \(\varpi\), Nr, \(\phi\) containing their linear, quadratic and interactions developed74,75,76:

Where \(\alpha _i, i = 0, 1, \cdots 9,\) are the regression coefficients to be determined. The accuracy of the estimated model is measured by utilizing analysis of variance (ANOVA) based on RSM in Table 6. Analysis of variance is a well-known statistical approach used to evaluate model accuracy and significance through descriptive analysis containing level of confidence \(R^2\), P-values, F-values, lack - of - fit, and error. For more accurate and statistically significant model the standard results typically obtained at 95\(\%\) of confidence level or 5\(\%\) (0.05) of significance level and sufficiently large F-values. In the present analysis quadratic term \(\phi ^2\) marked as insignificant term having p-values \(> 0.05\) while others are considered to be statistically significant as illustrated in Table 6. The model R-squared measure the variance in the response variable due to independent variables and particularly ascertain how well the data fits the regression model. The predicted model experimentally establish \(\hbox {R}^2\) value of 99.99\(\%\) and \(\hbox {R}^2\)-adjusted 99.98\(\%\), which confirms enhanced model precision and consistence in between response variable \(Nu_x\) and factors. The residual plots for the analysis of data distribution for response Nusselt number through normal probability, residual histogram, and observation order are presented in Fig. 41. The normal probability reveals that the residuals jointly align with straight line and the residual histogram further supporting, which ensures the normal distribution. Further, residual error for fits and run all confirm well fitted data and model accuracy. In general, the present analysis depicts normality, evaluating model estimations and consistence.

By using regression coefficients obtained after data analysis the quadratic model Eq. (31) of the Nusselt number \(Nu_x\) for the significant parameters can represented as:

The representation of Eq. (32) is graphically presented through contour plot and 3D surface plot for the interactions of two parameters out of three with the third parameter keeping as constant at their medium level interval (see Figs. 42, 43 and 44). The behavior of response variable \(Nu_x\) is significantly optimized for enhanced radiation parameter Nr and heat generation (\(\varpi\)), while volume fraction (\(\phi\)) remains fixed at its middle level as depicted Fig. 42. In addition, Fig. 43 illustrate the impacts of volume fraction (\(\phi\))and radiation parameter Nr on the heat transfer rate \(Nu_x\), leading that both variables enhance the response function and the effect of \(\varpi\) to \(Nu_x\) assumed to be insignificant. Consequently, at smaller values of Nr parameter and greater values of \(\varpi\) the heat transfer rate become decrease. In Fig. 44 the interaction between \(\varpi\) and \(\phi\) on the response function \(Nu_x\) is computed while taking Nr at a medium level, indicating that the response variable effectively improved for higher values of the both components of variables.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis is used to understand change of response variable with respect to variations in the independent variables. This is the most interesting method to determine the significant parameters and assess their effects on the response variable for effective design and simulation system77. In this study, the sensitivity analysis can be described by taking partial derivatives of the model for heat transfer rate in the Eq. (32) with respect to the coded variables \(\vartheta _1\), \(\vartheta _2\), \(\vartheta _3\) as follow:

The sensitivity analysis for heat transfer rate corresponds to the three parameters has been simulated at three distinct level values of \(\vartheta _1\), and \(\vartheta _2\) while \(\vartheta _3\) remains for medium level as shown in Table 7 and also presented graphically (see Figs. 45, 46 and 47). The heat transfer rate is presents the maximum sensitivity point of 1.4178 and lower sensitivity 0.4010 at same \(\varpi = 0.3\), \(Nr = 4\), \(\phi = 0.06\) parameter values as seen in Table 7. In general, The sensitivity result for response \(Nu_x\) shown that sensitivity to \(\varpi\) decreases as \(\varpi\) increases, demonstrating that \(\varpi\) has a strong negative effect on its own sensitivity. Conversely, the sensitivity with respect to Nr and \(\phi\) are positively enhancing as \(\varpi\) increase. Furthermore, The heat transfer rate \(Nu_x\) illustrates more sensitive towards \(\varpi (1.4178)\) relative to \(\phi (0.9898)\), and Nr (0.4425) sensitivity and also the same behavior is observed at three distinct cases for increasing radiation parameter.

Conclusions

The current study consider laminar, incompressible, unsteady nonlinear convection flow of ternary hybrid nanofluid in the spinning sphere passing in Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium. In this study, the three distinct nanoparticles containing silver (Ag), titanium dioxide \((TiO_2)\), and aluminum oxide \((Al_2O_3)\) in blood regarded as base fluid under electric and magnetic field influence. Moreover, the energy transfer has been discussed in the feature of quadratic thermal radiation, joule heating and heat generation including Catteo-Christov heat flux model in the presence of entropy analysis. The governing equations are delimited to nonlinear partial differential equations and the similarity variables are used to obtain the non-dimensional form of the conservation equations. The governing problem is solved numerically by using Keller-box scheme is adopted to solve the problem. The results demonstrate that key parameters such as the Casson parameter, magnetic field, rotation speed, inertia parameter, relaxation time, and thermal radiation yielded significantly impact on velocity, temperature, and entropy generation. Specifically, the key conclusions in this study are drawn as follows:

-

The linear velocity increases with higher values of Casson parameter (\(\beta\)), magnetic constant (Ma), and unsteadiness parameter (A), while the angular velocity decreases.

-

An increase in the rotation parameter (\(\lambda\)) and the Forchheimer term (\(F_d\)) results in a higher linear velocity field in the boundary region, but angular velocity decrease as the Forchheimer factor (\(F_d\)) rise.

-

The temperature profile decreases for greater thermal relaxation time parameter (\(\tau\)). In contrast, increase with thermal radiation (Nr) and Biot number (Bi).

-

However, both thermal radiation and Biot number reduces the rate of heat transfer.

-

Entropy generation decreases with stronger magnetic field (Ma) and Casson parameter (\(\beta\)) but rises with greater rotational effects (\(\lambda\)) and Brinkman number (Br).

-

An increase in the Brinkman number (Br) leads to decline Bejan number, whereas an opposite trend is observed for Casson (\(\beta\)) and magnetic field (Ma) parameters.

-

The heat transfer rate \(Nu_x\) obtain positive sensitivity with respect to \(\phi\) and Nr where as sensitivity correspond to respect to \(\varpi\) with highest optimal condition at different occasion 0.9898, 0.4425, and 1.4178, respectively for medium level of \(\phi\). Further, the experimental result established accuracy of the predicted model for confidence level \(R^2\) = 99.99\(\%\), \(R^2_{adjusted}\) = 99.99\(\%\).

These findings offer important insights into optimizing heat transfer in ternary hybrid nanofluid systems, which could be beneficial for advanced cooling systems, energy management, biomedical processes, and materials science applications. While the study provides a detailed theoretical analysis, future work should explore experimental validation and extend the model to include more complex geometries and boundary conditions.

Data availibility

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- A :

-

Unsteadiness parameter

- B :

-

Convective parameter

- \(B_i\) :

-

Biot parameter

- \(B_0\) :

-

Magnetic field strength (N m/A)

- \(C_{fx}, C_{fz}\) :

-

Skin friction drag

- \(C_p\) :

-

Heat capacity (\(J/ (m^3 \cdot K)\))

- \(E_0\) :

-

Electric field strength \((m kg/S^3A)\)

- \(E_f\) :

-

Electric parameter

- \(E_c\) :

-

Eckert number (\(m^2/s\))

- \(F_d\) :

-

Inertia constant

- f :

-

Nondimensional stream function

- g :

-

Nondimensional angular velocity

- \(Gr_x\) :

-

Grashof number

- \(h_f\) :

-

Convective heat factor (\(Wm^{-2}K^{-1}\))

- k :

-

Thermal conductivity (\(Wm^{-1}K^{-1}\))

- \(K_r\) :

-

Porosity parameter (\(W/(m \cdot K)\))

- Ma :

-

Magnetic parameter

- \(N_r\) :

-

Radiation parameter

- \(Nu_{x}\) :

-

Nusselt number

- Pr :

-

Prandtl number

- \(\varpi\) :

-

Heat generation

- \(Re_{x}\) :

-

Local Reynolds number

- \(\textbf{S}\) :

-

Angular velocity (m/s)

- T :

-

Fluid temperature (K)

- \(T_f\) :

-

Convective heat transfer (K)

- \(T_\infty\) :

-

Ambient temperature (K)

- (u, v, w):

-

Velocity component (m/s)

- (x, y) :

-

Cartesian coordinates(m)

- \(\eta\) :

-

Dimensionless similarity variable

- \(\lambda\) :

-

Rotation parameter

- \(\beta\) :

-

Casson parameter

- \(\beta _0, \beta _t\) :

-

Thermal expansion factors (\(K^{-1}\))

- \(\gamma\) :

-

Buoyancy parameter

- \(\gamma _1\) :

-

Nonlinear convection parameter

- \(\delta\) :

-

Slip velocity parameter

- \(\theta\) :

-

Dimensionless temperature

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Temperature gradient ratio

- \(\mu\) :

-

Dynamic viscosity (kg/ms)

- \(\upsilon\) :

-

Kinematic viscosity (\(m^2/s\))

- \(\sigma\) :

-

Electrical conductivity (s/m)

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density of fluid (\(kg/m^{3}\))

- \(\tau\) :

-

Thermal relaxation parameter

- thnf :

-

Ternary hybrid nanofluid

- hnf :

-

Hybrid nanofluid

- nf :

-

Nanofluid

- f :

-

Base fluid (blood)

- \(\infty\) :

-

Free stream circumstances

- w :

-

Condition at the surface

References

Guedri, K. et al. Thermal flow for radiative ternary hybrid nanofluid over nonlinear stretching sheet subject to Darcy-Forchheimer phenomenon. Math. Probl. Eng.2022(1), 3429439 (2022).

Choi, S. U. & Eastman, J. A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles (Argonne National Lab. ANL, Argonne, 1995).

Arif, M., Kumam, P., Kumam, W. & Mostafa, Z. Heat transfer analysis of radiator using different shaped nanoparticles water-based ternary hybrid nanofluid with applications: A fractional model. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.31, 101837 (2022).

Yu, L., Li, Y., Puneeth, V., Znaidia, S., Shah, N.A, Manjunatha. S., et al. Heat transfer optimisation through viscous ternary nanofluid flow over a stretching/shrinking thin needle. Numerical Heat Transfer, Part A: Applications. 1–15 (2023).

Arif, M., Di Persio, L., Kumam, P., Watthayu, W. & Akgül, A. Heat transfer analysis of fractional model of couple stress Casson tri-hybrid nanofluid using dissimilar shape nanoparticles in blood with biomedical applications. Sci. Rep.13(1), 4596 (2023).

Mahmood, A., Jamshed, W. & Aziz, A. Entropy and heat transfer analysis using Cattaneo-Christov heat flux model for a boundary layer flow of Casson nanofluid. Results Phys.10, 640–9 (2018).

Ibrahim, W. & Makinde, O. Magnetohydrodynamic stagnation point flow and heat transfer of Casson nanofluid past a stretching sheet with slip and convective boundary condition. J. Aerosp. Eng.29(2), 04015037 (2016).

Jamshed, W. et al. Features of entropy optimization on viscous second grade nanofluid streamed with thermal radiation: A Tiwari and Das model. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.27, 101291 (2021).

Ibrahim, W. & Kenea, G. Nonlinear convection flow of a micropolar nanofluid past a stretching sphere with convective heat transfer. J. Nanofluids13(2), 407–22 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Modelling and analysis of heat transfer in MHD stagnation point flow of Maxwell nanofluid over a porous rotating disk. Alex. Eng. J.91, 237–48 (2024).

Nasir, S. et al. Heat transport study of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow under magnetic dipole together with nonlinear thermal radiation. Appl. Nanosci.12(9), 2777–88 (2022).

Maskeen, M. M., Zeeshan, A., Mehmood, O. U. & Hassan, M. Heat transfer enhancement in hydromagnetic alumina-copper/water hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.138, 1127–36 (2019).

Abd-Elmonem, A. et al. Thermal characteristics of hybrid Nanofluid (Cu-Al2O3) flow through Darcy porous medium with chemical effects via numerical successive over relaxation technique. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.65, 105538 (2025).

Yang, D. et al. CFD analysis of paraffin-based hybrid (Co-Au) and trihybrid (Co-Au-ZrO2) nanofluid flow through a porous medium. Nanotechnol. Rev.13(1), 20240024 (2024).

Mahboobtosi, M., Hosseinzadeh, K. & Ganji, D. Entropy generation analysis and hydrothermal optimization of ternary hybrid nanofluid flow suspended in polymer over curved stretching surface. Int. J. Thermofluids20, 100507 (2023).

Mumtaz, M., Islam, S., Ullah, H. & Shah, Z. Chemically reactive MHD convective flow and heat transfer performance of ternary hybrid nanofluid past a curved stretching sheet. J. Mol. Liq.390, 123179 (2023).

Jan, A., Mushtaq, M. & Hussain, M. Heat transfer enhancement of forced convection magnetized cross model ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching cylinder: non-similar analysis. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow106, 109302 (2024).

Sarada, K. et al. Impact of exponential form of internal heat generation on water-based ternary hybrid nanofluid flow by capitalizing non-Fourier heat flux model. Case Studi. Therm. Eng.38, 102332 (2022).

Sajid, T. et al. Radiative and porosity effects of trihybrid Casson nanofluids with Bödewadt flow and inconstant heat source by Yamada-Ota and Xue models. Alex. Eng. J.66, 457–73 (2023).

Riaz, S., Afzaal, M.F., Wang, Z., Jan, A. & Farooq, U. Numerical heat transfer of non-similar ternary hybrid nanofluid flow over linearly stretching surface. Num. Heat Transf. Part A Appl.. 1–15 (2023).

Alwawi, F. A., Swalmeh, M. Z. & Hamarsheh, A. S. Computational simulation and parametric analysis of the effectiveness of ternary nano-composites in improving magneto-micropolar liquid heat transport performance. Symmetry15(2), 429 (2023).

Sharma, B. K., Sharma, P., Mishra, N. K., Noeiaghdam, S. & Fernandez-Gamiz, U. Bayesian regularization networks for micropolar ternary hybrid nanofluid flow of blood with homogeneous and heterogeneous reactions: Entropy generation optimization. Alex. Eng. J.77, 127–48 (2023).

Naidu, K. K., Babu, H. D., Reddy, H. S. & Narayana, S. P. Magneto-Stefan blow enhanced heat and mass transfer flow in non-Newtonian ternary hybrid nanofluid across the nonlinear elongated surface. Num. Heat Transf. Part B Fundam. (2024).

Casson, N. Flow equation for pigment-oil suspensions of the printing ink-type. Rheol. Disperse Syst. 84–104 (1959).

Jamshed, W. et al. Evaluating the unsteady Casson nanofluid over a stretching sheet with solar thermal radiation: An optimal case study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.26, 101160 (2021).

Prabhakar Reddy, B. & Sademaki, L. J. A Numerical study on Newtonian heating effect on heat absorbing MHD Casson flow of dissipative fluid past an oscillating vertical porous plate. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci.2022(1), 7987315 (2022).

Reddy, B. P., Makinde, O. & Hugo, A. A computational study on diffusion-thermo and rotation effects on heat generated mixed convection flow of MHD Casson fluid past an oscillating porous plate. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf.138, 106389 (2022).

Sademaki, L. J., Shamshuddin, M., Reddy, B. P. & Salawu, S. Unsteady Casson hydromagnetic convective porous media flow with reacting species and heat source: Thermo-diffusion and diffusion-thermo of tiny particles. Partial Differ. Equations Appl. Math.11, 100867 (2024).

Sankari, M. S. et al. Williamson MHD nanofluid flow via a porous exponentially stretching sheet with bioconvective fluxes. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.59, 104453 (2024).

Alqahtani, A. M. et al. Heat and mass transfer through MHD Darcy Forchheimer Casson hybrid nanofluid flow across an exponential stretching sheet. ZAMM J. Appl. Math. Mech. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik.103(6), e202200213 (2023).

Wang, F. et al. Computational examination of non-Darcian flow of radiative ternary hybridity Casson nanoliquid through moving rotary cone. J. Comput. Design Eng.10(4), 1657–76 (2023).

Abbas, M. et al. Numerical simulation of Darcy-Forchheimer flow of Casson ternary hybrid nanofluid with melting phenomena and local thermal non-equilibrium effects. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.60, 104694 (2024).

Babu, D. H. et al. Numerical and neural network approaches to heat transfer flow in MHD dissipative ternary fluid through Darcy-Forchheimer permeable channel. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.60, 104777 (2024).

Khan, M. N. et al. Flow and heat transfer insights into a chemically reactive micropolar Williamson ternary hybrid nanofluid with cross-diffusion theory. Nanotechnol. Rev.13(1), 20240081 (2024).

Mohanty, D., Mahanta, G. & Shaw, S. Irreversibility and thermal performance of nonlinear radiative cross-ternary hybrid nanofluid flow about a stretching cylinder with industrial applications. Powder Technol.433, 119255 (2024).

Jamshed, W. & Aziz, A. Cattaneo-Christov based study of TiO 2-CuO/EG Casson hybrid nanofluid flow over a stretching surface with entropy generation. Appl. Nanosci.8(4), 685–98 (2018).

Kumaraswamy Naidu, K., Harish Babu, D., Harinath Reddy, S. & Satya, Narayana P. Radiation and partial slip effects on magnetohydrodynamic Jeffrey nanofluid containing gyrotactic microorganisms over a stretching surface. J. Therm. Sci. Eng. Appl.13(3), 031011 (2021).

Naqvi, S. M. R. S. et al. Numerical simulations of hybrid nanofluid flow with thermal radiation and entropy generation effects. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.40, 102479 (2022).

Babu, D. H., Reddy, S. H., Naidu, K. K., Narayana, P. V. S. & Venkateswarlu, B. Numerical investigation for entropy-based magneto nanofluid flow over non-linear stretching surface with slip and convective boundary conditions. ZAMM J. Appl. Math. Mech. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Mathematik und Mechanik.103(10), e202300006 (2023).

Babu, D., Naidu, K., Narayana, P. & Chalapathi, T. The radiative composite (NiCr+ TC4)/H2O) mixture nanofluid flow over a non-linear spinning stretching sheet with the impact of variable Lorenz force and slip condition 1–15 (Part A Appl, Num Heat Transf, 2023).

Rehman, M. I. U. et al. Effect of Cattaneo-Christov heat flux case on Darcy-Forchheimer flowing of Sutterby nanofluid with chemical reactive and thermal radiative impacts. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.42, 102737 (2023).

Noreen, S. et al. Comparative study of ternary hybrid nanofluids with role of thermal radiation and Cattaneo-Christov heat flux between double rotating disks. Sci. Rep.13(1), 7795 (2023).

Ali, G. et al. Heat transfer analysis of unsteady MHD slip flow of ternary hybrid Casson fluid through nonlinear stretching disk embedded in a porous medium. Ain Shams Eng. J.15(2), 102419 (2024).

Irfan, M., Farooq, M. A. & Iqra, T. A new computational technique design for EMHD nanofluid flow over a variable thickness surface with variable liquid characteristics. Front. Phys.8, 66 (2020).

Kaneez, H. et al. Thermal analysis of magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) Casson fluid with suspended iron (II, III) oxide-aluminum oxide-titanium dioxide ternary-hybrid nanostructures. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.586, 171223 (2023).

Usman, M., Gul, T., Khan, A., Alsubie, A. & Ullah, M. Z. Electromagnetic couple stress film flow of hybrid nanofluid over an unsteady rotating disc. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf.127, 105562 (2021).

Hussain, M., Farooq, U. & Sheremet, M. Nonsimilar convective thermal transport analysis of EMHD stagnation Casson nanofluid flow subjected to particle shape factor and thermal radiations. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf.137, 106230 (2022).

Jakeer, S., Reddy, S., Rashad, A., Rupa, M. L. & Manjula, C. Nonlinear analysis of Darcy-Forchheimer flow in EMHD ternary hybrid nanofluid (Cu-CNT-Ti/water) with radiation effect. Forces Mech.10, 100177 (2023).

Gupta, S., Sangtani, V. S., Jain, C. P. & Jain, P. K. Cattaneo-Christov heat and mass model for radiative EMHD Aluminum Alloys (7072/7072+7075 T6) with Transformer base oil hybrid nanofluid over an exponentially stretching sheet. BioNanoScience. 1-19, (2024).

Lone, S. A. et al. Electrically conducting mixed convective flow of a hybrid nanoliquid over a rotating sphere with nonlinear thermal radiation. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.49, 103165 (2023).

Mahdy, A. & Ahmed, S. E. Unsteady MHD convective flow of non-Newtonian Casson fluid in the stagnation region of an impulsively rotating sphere. J. Aerosp. Eng.30(5), 04017036 (2017).

Mahdy, A., Chamkha, A. J. & Nabwey, H. A. Entropy analysis and unsteady MHD mixed convection stagnation-point flow of Casson nanofluid around a rotating sphere. Alex. Eng. J.59(3), 1693–703 (2020).

Ali, B. et al. Tangent hyperbolic nanofluid: Significance of Lorentz and buoyancy forces on dynamics of bioconvection flow of rotating sphere via finite element simulation. Chin. J. Phys.77, 658–71 (2022).

Gul, T. et al. Mixed convection stagnation point flow of the blood based hybrid nanofluid around a rotating sphere. Sci. Rep.11(1), 7460 (2021).

Gamachu, D., Ibrahim, W. & Bijiga, L. K. Nonlinear convection unsteady flow of electro-magnetohydrodynamic Sutterby hybrid nanofluid in the stagnation zone of a spinning sphere. Results Phys.49, 106498 (2023).

Gamachu, D., Ibrahim, W. & Bijiga, L. K. Nonlinear convection unsteady flow of electro-magnetohydrodynamic Sutterby hybrid nanofluid in the stagnation zone of a spinning sphere. Results Phys.49, 106498 (2023).

Kenea, G. & Ibrahim, W. Nonlinear convection stagnation point flow of Oldroyd-B nanofluid with non-Fourier heat and non-Fick’s mass flux over a spinning sphere. Sci. Rep.14(1), 841 (2024).

Hayat, T., Ullah, I., Alsaedi, A. & Ahamad, B. Simultaneous effects of nonlinear mixed convection and radiative flow due to Riga-plate with double stratification. J. Heat Transf.140(10), 102008 (2018).

Chen, H., He, P., Shen, M. & Ma, Y. Thermal analysis and entropy generation of Darcy-Forchheimer ternary nanofluid flow: A comparative study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.43, 102795 (2023).

Mandal, G. & Pal, D. Mixed convective-quadratic radiative MoS 2-SiO 2/H 2 O hybrid nanofluid flow over an exponentially shrinking permeable Riga surface with slip velocity and convective boundary conditions: entropy and stability analysis. Num. Heat Transf. Part A Appl.85(14), 2315–40 (2024).

Anilkumar, D. & Roy, S. Self-similar solution of the unsteady mixed convection flow in the stagnation point region of a rotating sphere. Heat Mass Transf.40, 487–93 (2004).

Al Oweidi, K. F. et al. Partial differential equations of entropy analysis on ternary hybridity nanofluid flow model via rotating disk with hall current and electromagnetic radiative influences. Sci. Rep.12(1), 20692 (2022).

Alnahdi, A. S., Nasir, S. & Gul, T. Ternary Casson hybrid nanofluids in convergent/divergent channel for the application of medication. Therm. Sci.27(Spec. issue 1), 67–76 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Insights into the thermal characteristics and dynamics of stagnant blood conveying titanium oxide, alumina, and silver nanoparticles subject to Lorentz force and internal heating over a curved surface. Nanotechnol. Rev.12(1), 20230145 (2023).

Makinde, O. D. Stagnation point flow with heat transfer and temporal stability of ferrofluid past a permeable stretching/shrinking sheet. In Defect and diffusion forum. Vol. 387, pp. 510–522(Trans Tech Publ, 2018).

Seth, G., Kumar, R. & Bhattacharyya, A. Entropy generation of dissipative flow of carbon nanotubes in rotating frame with Darcy-Forchheimer porous medium: A numerical study. J. Mol. Liquids268, 637–46 (2018).

Jakeer, S. et al. Entropy analysis on EMHD 3D micropolar tri-hybrid nanofluid flow of solar radiative slendering sheet by a machine learning algorithm. Sci. Rep.13(1), 19168 (2023).

Mohanty, D., Mahanta, G., Shaw, S. & Sibanda, P. Thermal and irreversibility analysis on Cattaneo-Christov heat flux-based unsteady hybrid nanofluid flow over a spinning sphere with interfacial nanolayer mechanism. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.148(21), 12269–84 (2023).

Keller, H. B. A new difference scheme for parabolic problems. In Numerical Solution of Partial Differential Equations–II. 327–50 (Elsevier, 1971).

Dinarvand, S. Nodal/saddle stagnation-point boundary layer flow of CuO-Ag/water hybrid nanofluid: A novel hybridity model. Microsyst. Technol.25(7), 2609–23 (2019).

Mishra, S., Baag, S., Pattnaik, P. & Panda, S. Sensitivity analysis on enhanced thermal transport in Eyring-Powell nanofluid flow: Investigating over a radiating convective Riga plate with non-uniform heat source/sink under flux conditions. J. Therm. Anal. Calorimetry149(2), 711–28 (2024).

Farooq, U., Liu, T., Alshamrani, A. & Farooq, U. MHD stagnation point flow of Casson hybrid nanofluid with bioconvection for biomedical skin patch applications. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf.245, 127048 (2025).

Farooq, U., Liu, T., Alshamrani, A. & Alam, M. M. Sensitivity of activation energy and thermal radiation in dihydrogen oxide based nanofluid performance in PTSC. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy129, 253–64 (2025).

Islam, S., Siddiki, M. N. A. A. & Islam, M. S. Numerical simulation and sensitivity analysis using RSM on natural convective heat exchanger containing hybrid nanofluids. Math. Probl. Eng.2024(1), 2834556 (2024).

Felicita, A., Kumar, P., Ajaykumar, A., Nagaraja, B. & Al-Mdallal, Q. Application of design of experiments for single-attribute optimization using response surface methodology for flow over non-linear curved stretching sheet. Alex. Eng. J.100, 246–59 (2024).

Senbagaraja, P. & De, P. Sensitivity analysis on electro-osmotic flow of EMHD tangent hyperbolic nanofluid through porous rotating disk with variable thermal conductivity, Stefan blowing and thermal radiation. Multiscale Multidiscip. Model. Exp. Design8(1), 65 (2025).

Rajeswari, P. M. & De, P. Shape factor and sensitivity analysis on stagnation point of bioconvective tetra-hybrid nanofluid over porous stretched vertical cylinder. BioNanoScience14(3), 3035–58 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mr. Gadisa drafted the manuscript and performed the numerical computations. Prof. Wubshet supervised the research, provided theoretical insights, and critically reviewed the manuscript for technical accuracy. Both authors contributed to discussions, and manuscript refinement, and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kenea, G., Ibrahim, W. Thermal enhancement of ternary hybrid Casson nanofluid in porous media: a sensitivity analysis study. Sci Rep 16, 2400 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21154-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-21154-8