Abstract

This study presents the fabrication of highly photosensitive undoped zinc oxide (ZnO) thin films for vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) radiation detection, covering the wavelength range of 100–200 nm. ZnO films were deposited using hybrid pulsed reactive magnetron sputtering, assisted by ECWR (electron cyclotron wave resonance) plasma. Control of the ECWR power (PECWR), ranging from 0 to 380 W, played a crucial role in enhancing the films’ photoconductive properties. At PECWR = 200 W, the photosensitivity increased by 8 orders of magnitude compared to films deposited without ECWR assistance. This improvement was attributed to a sharp reduction in dark current due to lower defect density. Photoluminescence and cathodoluminescence spectra revealed a significant reduction in defect-related emissions for films deposited at PECWR = 200 W, confirming fewer intrinsic defects. Raman spectroscopy also showed a decrease in defect-related vibrational modes in the same films. Time-Resolved Microwave Conductivity (TRMC) measurements further supported these findings, demonstrating rapid recombination of charge carriers at 200 W, indicative of low trap densities. These results suggest that precise control of ECWR power allows for optimization of the defect concentration and crystallinity in ZnO films, paving the way for the development of high-sensitivity VUV photodetectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Detection of high-energy photons in the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) region presents unique challenges due to the need for specialized materials and conditions. Spanning the wavelength range from 100 to 200 nm1, VUV radiation is strongly absorbed by oxygen in air, thus requiring its propagation through vacuum. Despite these challenges, the growing demand for VUV sensors in applications ranging from space science to surface treatment has driven significant advancements in both VUV detectors and light-emitting devices2,3,4. Molecular spectroscopy, gas chromatography, surface sterilization, photochemical processing, surface treatment, and photolithography are some examples of scientific and technological research that rely on VUV radiation. Recently, there has also been increasing reliance on VUV radiation in space science where one of the most effective ways of monitoring evolution of stars and space weather is through the detection of these high energy radiation5,6,7. Scintillators are being developed as intermediary materials that absorb the VUV radiation, subsequently converting it to UV or visible radiation via its luminescence8,9,10,11,12. Scintillators work through the excitation of electrons upon absorption of radiation by the scintillator material, followed by the de-excitation of electrons that result to the emission of photons (luminescence). The conversion of high energy VUV to lower energy UV or visible radiation enables the detection of the luminescence using a photodetector such as a photomultiplier tube that converts the luminescence to an electrical signal. A more efficient approach is to use photoconductive detectors, which directly convert VUV light into electrical signals, bypassing the need for intermediary scintillator materials and improving response time and sensitivity. In photoconductive detectors, the absorbed radiation excites electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, leading to the generation of electron-hole pairs that are free to move through the material. When an external electric field (E-field) is applied across the photoconductive material, the photo-generated carriers move in the direction of the E-field registering as photocurrent. The magnitude of the photocurrent is indicative of the number of photons absorbed, thus providing a direct measurement of the intensity of the incident VUV radiation.

Wide bandgap semiconductors are requisite materials for photoconductive detectors due to their ability to efficiently generate electron-hole pairs under high-energy photon exposure. Some examples of these are gallium nitride (GaN)13, aluminum nitride (AlN)14,15, titanium dioxide (TiO2)16,17,18, magnesium oxide (MgO)19, and zinc oxide (ZnO)20, which have larger energy gaps compared to typical semiconductors, enabling them to effectively detect VUV radiation. Diamond has also been explored as a VUV photodetector but is cost-prohibitive and necessitates sufficiently low defect concentration of n-type and p-type dopants21,22,23. Compared to diamond, p- and n-type doping is easier in cubic boron nitride (c-BN) and therefore it has better photoconductivity characteristics, but the quality of c-BN is still low24,25. Recently, amorphous boron nitride26, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN)27,28, and fluorides29,30,31,32,33,34 have also attracted attention as VUV photodetectors.

ZnO has excellent optical and electrical properties as a direct transition semiconductor with a large band gap energy of about 3.37 eV and high exciton binding energy of 60 meV35. Owing to these characteristics, it is ubiquitous in a wide range of applications including transparent conducting films, UV sensors, and transistors. ZnO films have not yet been investigated as a photoconductive detector in the VUV region. As a VUV photoconductive detector, it is essential to control its electrical conduction properties which are strongly influenced by intrinsic defects and crystallinity as these affect charge carrier density and mobility. Therefore, it is necessary to control the population of defects and the degree of crystallinity to optimize their photoconductivity especially in the VUV region. Previous works have investigated the effect of different deposition methods and parameters on the crystallinity and defects of ZnO thin films, including the effect of increasing the substrate temperature in improving the crystallinity and reducing defect density using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) and pulsed laser deposition (PLD)36,37, the influence of increasing oxygen pressure in making more transparent films at low temperature by PLD37, effect of annealing temperature and annealing atmosphere on the quality of ZnO films fabricated by molecular beam epitaxy (MBE)38, controlling the defects and crystallite size by regulating the oxygen partial pressure and annealing using vacuum DC sputtering39, the effect of substrate on films deposited by PLD40, and the effect of RF power on the crystallinity and optical properties of RF magnetron-sputtered films41. Films deposited at 175 W RF power had poor crystalline quality because of severe surface damage brought about by a very fast reaction rate41. In this work, we use pulsed reactive magnetron sputtering operating in the medium-frequency range (MF magnetron) assisted by an electron cyclotron wave resonance (ECWR) plasma (MF + ECWR magnetron)42 to deposit µm-thick ZnO films on soda-lime glass (SLG) substrates. We show that the amount of defects and the crystallinity of ZnO films can be easily controlled by changing the ECWR power. By doing so, we are able to tune the electrical conduction properties of ZnO films and determine the optimal ECWR power for the development of highly photosensitive ZnO films in the VUV region.

Results and discussion

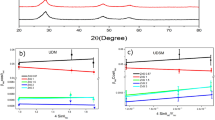

ZnO films were deposited on SLG substrates using MF + ECWR with ECWR power (PECWR) of 0 W (MF only), 100 W, 200 W, 300 W, and 380 W. For all PECWR, the MF power was kept constant at 300 W. Figure 1a shows the grazing incidence x-ray diffraction (GIXRD) spectra of the grown films. All films grew along the c-axis and have a wurtzite-type structure with the dominant peak along the (002) plane. In general, the c-axis orientation is increasingly favored as PECWR is increased as shown in Fig. 1b; Table 1. The dominant peak broadens and shifts to the left for PECWR equal to or greater than 300 W, as shown in Fig. 1c and d. The full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) of the dominant (002) peak is 0.180 deg., 0.175 deg., 0.175 deg., 0.254 deg., and 0.254 deg. For PECWR 0 W, 100 W, 200 W, 300 W, and 380 W, respectively. This indicates that the tensile stress increases as the power is increased. A higher ECWR power translates to a higher energy and thermal flux at the surface of the substrate (see Supplementary Fig. S1), which results to a greater thermal heating during deposition. Due to the big difference in the thermal expansion coefficients of the soda-lime glass substrate and the ZnO layer (9.17e–6 K– versus 4.3e–6 K–1), this additional plasma-induced heating of the substrate can ultimately lead to a higher stress for the layers prepared at PECWR of 300 W and higher. It should be noted that the individual ZnO films have different thicknesses, ranging from 2.1 μm (100 ECWR) to 3.8 μm (0 ECWR). The different thicknesses could also have a non-negligible effect on the magnitude of the internal stress in the ZnO films. Figure 1e shows that the films deposited with PECWR of 300 W and 380 W possess a significantly smaller crystallite size along the (002) direction. A decrease in the crystallite size for increasing PECWR is observed for each of the directions indexed in the XRD spectra, as summarized in Table 2. This phenomenon could be related to the higher deposition rate at higher ECWR powers, as shown in Fig. 1f. A higher deposition rate leads to the formation of smaller crystallites because atoms accumulate on the surface faster than they have time to reorganize into larger crystals.

(a) GIXRD spectra of ZnO films deposited with ECWR powers (PECWR) of 0 W (MF only), 100 W, 200 W, 300 W, and 380 W. (b) Proportion of c-axis orientation ((002) peak) of the GIXRD spectra. The dominant peak along the (002) direction (c) broadens and (d) shifts to the left as PECWR is increased. (e) Crystallite size of the dominant (002) peak as a function of PECWR shows a significant decrease in crystallite size for films deposited at PECWR of 300 W and 380 W. (f) Deposition rate as a function of ECWR power.

In Fig. 1f, we observe a significant increase in the deposition rate of ZnO films with the applied ECWR power up to 300 W, while the mid-frequency (MF) power applied to the magnetron discharge PMF remains constant at 300 W. However, at PECWR = 380, the deposition rate decreases markedly compared to PECWR = 300. The initial increase in the deposition rate can be attributed to the rise in the zinc target’s surface temperature at higher PECWR , leading to increased evaporation of zinc atoms. This is supported by the high vapor pressure of zinc metal43. However, beyond PECWR = 300 W, the deposition rate decreases due to a combination of plasma-related effects. As shown in Fig. 2, at PECWR = 380 W, the ion density (ni) in the plasma increases significantly, reaching ni ≈ 1017 m–3. It is well established that in sputtering systems with such high ion densities, a significant fraction of sputtered particles becomes ionized. This phenomenon, observed in systems utilizing magnetron discharges combined with RF ICP plasmas44,45, and in HiPIMS (high-power impulse magnetron sputtering) systems46,47,48,49, leads to the “back attraction” effect. Here, positively ionized sputtered atoms are drawn back toward the negatively biased magnetron target due to electrostatic forces and the electric field within the cathode sheath. This back attraction effect reduces the net flux of sputtered material reaching the substrate, thereby lowering the deposition rate. The substantial ionization of sputtered zinc atoms at high PECWR is indirectly supported by Supplementary Fig. S7, which shows strong Zn+ ion emission lines with a peak at PECWR = 380 W. While these observations provide a plausible explanation, a precise quantification of the ionization fraction of sputtered zinc particles is necessary for a definitive understanding. Techniques such as gridded quartz crystal microbalance (QCM)45,50 or magnetic QCM51, alongside a detailed physical model, would be valuable for further validation.

FE-SEM images showing the surface morphology of the ZnO films deposited at PECWR of 0 W, 100 W, 200 W, 300 W, and 380 W. The magnification of the SEM images is 20000x. FE-SEM images for other magnifications can be seen in Supplementary Fig. S8.

The surface morphology of the films (see Fig. 3) obtained by a low acceleration voltage (5 kV) field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) shows that the crystallite size appears to decrease as PECWR is increased, with the crystallite size being significantly smaller for the films deposited with PECWR of 300 W and 380 W. This is consistent with the trend observed from the XRD spectra.

Figure 4 shows the Raman spectra of the ZnO films. The peaks at 98 cm–1, 334 cm–1, 439 cm–1, and 586 cm–1 (identified by black fonts in the graph) are typical ZnO normal modes assigned to E2 (Low), E2 (High)-E2 (Low), and E2 (High), and E2 (LO) modes, respectively52,53. In the films deposited with PECWR of 0 W and 100 W, additional peaks are observed at 276 cm–1, 511 cm–1, and 581 cm–1 (identified by red fonts in the graph). These peaks are associated with defects in the ZnO crystal and individual bonds52,54. The Raman spectra of the films prepared with PECWR of 200 W, 300 W, and 380 W do not contain any of the peaks associated with defects. The calculated areas of the 276 cm–1 and 511 cm–1 defect-related peaks reveal that the amount of defects decreases as the PECWR increases, appearing to almost be suppressed when the PECWR is increased to at least 200 W. To confirm this observation, the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the films were obtained as shown in Fig. 5a. The peak in the UV wavelength region around 380 nm is the near-band-edge luminescence from ZnO while the broad peak in the visible wavelength region originates from defects, namely zinc interstitials, oxygen interstitials, neutral oxygen vacancy, doubly ionized oxygen vacancy, and excess oxygen involving Zn vacancy complexes42 that serve as luminescence centers. The defect-related luminescence is significantly more intense in the films deposited with PECWR of 0 W and 100 W compared to films deposited with PECWR of 200 W, 300 W, and 380 W, as shown in Fig. 5b. A similar behavior is observed in the cathodoluminescence (CL) spectra of the films shown in Fig. 5c and d. These findings are also supported by the transmittance spectra (see Supplementary Fig. S9). ZnO layers deposited by MF + ECWR (colored curves) exhibit significantly increased transmittance in the visible region above 400 nm compared to the ZnO layer prepared by MF without ECWR (see black curves in Figs. S9a and S9b). This increased absorption in the visible wavelength region suggests a higher presence of defects, particularly oxygen vacancies or zinc interstitials, which can absorb light with lower energy (longer wavelength) than the standard bandgap absorption. On the other hand, for the ZnO films prepared by MF + ECWR (colored curves), a relatively sharp absorption edge around 370 nm (3.3 eV) is observed. Therefore, the results from the transmission, absorption, PL and CL spectra confirm the observation from the Raman spectra that the number of defects decreases as the PECWR increases. Figure 5a and c also show that the intensity of the 380-nm UV luminescence is highest for the film deposited with PECWR of 100 W and is lowest for the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W. The increase in UV emission from 0 W to 100 W is associated with a decrease in defect density, as evidenced by the Raman spectroscopy results shown in Fig. 4. The presence of defects reduces UV emission due to increase radiative recombination in the visible light range and non-radiative recombination processes. The simultaneous decrease in grain size (as visible in SEM images—Fig. 3) lead to a decrease in UV intensity due to an increase in surface recombination, which is non-radiative55. The decrease in the UV intensity in both the PL and CL spectra alludes to the poorer crystallinity of the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W as it is consistent with the broadening of the dominant (002) diffraction peak at PECWR power equal to or greater than 300 W, as discussed in the preceding paragraphs (see Fig. 1c). The ratio between the broad visible and the narrow UV emission intensities (Supplementary Fig. S10) decreases as the PECWR increases from 0 W to 100 W and 200 W owing to the reduction of the number of defects. The film deposited with PECWR of 200 W, which also had the narrowest (002) diffraction peak and the weakest visible emission intensity, exhibited the smallest ratio. As PECWR is further increased to 300 W and 380 W, it can be seen that the ratio also increases, signifying that not only did the films have poorer crystallinity (broader (002) diffraction peak), but also the defect-related visible luminescence has increased. As the ECWR power increases from 0 up to 200 W, the number of defects in the crystal lattice decreases as observed from the Raman spectra (see Fig. 4) and the visible PL and CL spectra (see Fig. 5). However, an ECWR power that is very high (300 W and 380 W) can lead to the formation of new defects due to a very high ion flux to the substrate (see Supplementary Fig. S2). At the same time, the very high ECWR power leads to a reduction in the size of the crystallites (see Fig. 1e). As the crystallite size decreases, the relative amount of surface atoms compared to bulk atoms increases. This effect leads to the formation of more surface defects, which create electronic states within the band gap of ZnO. Therefore, the reduction in crystallite size can result in an increase in defect-related luminescence in the visible region.

In order to understand the influence of plasma parameters on the properties of the prepared ZnO layers, the electron temperature and plasma density were measured during the deposition using a modified RF probe56. This measurement was supplemented by optical emission spectroscopy and measurement of the thermal flow to the substrate using a calorimetric probe. The dependence of the electron temperature and plasma density on the ECWR power is shown in Fig. 2 and supporting data from these measurements are presented in Supplementary Figs. S1 to S7. The plasma density increased from 4 × 1016 m–3 at PECWR of 0 W to three times this value at PECWR of 380 W, confirming that as the ECWR power increases, the plasma density also increases36. At the same time, the effective electron temperature dropped from 9 eV at PECWR of 0 W to less than half of that value at PECWR of 380 W. This significant drop in electron temperature can also be indicated using emission spectroscopy (see Supplementary Fig. S6) Therefore we can conclude that ECWR adds relatively “cold” electrons to the plasma, which, owing to their high concentration, effectively contribute to the dissociation of oxygen molecules (the bond-dissociation energy of the O2 molecule is only 5.15 eV) and also (albeit to a lesser extent) to the excitation and ionization of sputtered Zn particles. Both of these effects are very much visible through the emission spectra (see Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5). Excitation and ionization of Zn particles and dissociation of O₂ molecules in plasma have a direct impact on the defect structure of ZnO films. These processes can influence the growth dynamics, mutual reactivity, chemical composition, and quality of the ZnO layer, which can affect the concentration of various types of defects. For example, oxygen dissociation in the plasma can affect the availability of atomic oxygen. If there is a lack of dissociated oxygen in the plasma, oxygen vacancies (VO) may form in the growing ZnO layer. Conversely, if enough atomic or ionized oxygen is present, the number of oxygen vacancies can be reduced. On the other hand, a high concentration of ionized zinc can lead to an excess of zinc atoms in the ZnO structure. These atoms may occupy interstitial positions (Zni) in the crystal lattice, which are also defects that affect the electrical and optical properties of the film. If the zinc ion flux is too high (due to excessive ion flow of zinc), the number of zinc interstitials may increase, leading to undesired defects. The growth of high-quality ZnO layers is therefore very sensitive to the magnitude of the applied ECWR power, as its value strongly influences the aforementioned plasma properties. This consideration also helps in understanding why the “coldness” of the ECWR plasma is very relevant. It supports the (laudable) dissociation of oxygen molecules rather than the (excessive) ionization of zinc (See Supplementary Fig. S7), which could result in unwanted (Zni) defects.

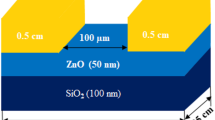

A pair of interdigitated aluminum electrodes were deposited on the ZnO films by vacuum evaporation, as shown in Fig. 6a. The current under forward and reverse bias voltages did not exhibit rectification (see Supplementary Fig. S11), indicating that the film and the electrode are in ohmic contact. The photocurrent (Iphoto) was measured under irradiation of a deuterium lamp emitting VUV radiation from about 115 nm to 170 nm, with a peak emission around 160 nm. The dark current (Idark) was measured when the lamp is off. Since the energy corresponding to the VUV wavelength of the light source used (7.75 eV) is higher than the work function of aluminum (4.1 eV), electrons can be emitted also from the surface of the aluminum electrode due to the photoelectric effect when the ZnO layer is illuminated. However, since the electrodes on all samples have the same shape, this effect does not influence the comparison between different ZnO layers. The penetration depth of VUV radiation with a wavelength of 160 nm within the ZnO layer is approximately 50 nm (see Supplementary Fig. S13). Considering the thickness of all ZnO layers presented here (2 to 4 micrometers), this experiment primarily provides information about the surface part of the ZnO layer.

(a) Schematic diagram of the aluminum electrodes deposited on the ZnO film to measure the photoconductivity of the films when irradiated by a VUV lamp emitting from about 115 nm to 1700 nm. (b) I-V characteristics of the ZnO films for applied bias voltages ranging from 0 V to 5 V. (c) Photosensitivity of the ZnO films for an applied bias voltage of 5 V.

Figure 6b shows the current-voltage (I-V) characteristics of the ZnO films for applied bias voltages ranging from 0 V to 5 V. The photosensitivity (S) of the films were calculated according to Eq. 1, summarized in Table 3, and shown in Fig. 6c.

The film deposited using MF only (PECWR = 0 W) is only slightly photosensitive as the photocurrent is almost the same as the dark current. At PECWR of 100 W, the photocurrent is one order of magnitude greater than the dark current and the film starts to be photosensitive. Increasing the ECWR power further to 200 W significantly increases the photosensitivity of the ZnO photodetector. Remarkably, the photocurrent is 9 orders of magnitude greater than the dark current.

The significant decrease in the dark current resulted to a substantial improvement in photosensitivity, whereby the photosensitivity increased by 8 orders of magnitude compared to the film deposited at PECWR of 0 W. The decrease in dark current is primarily attributed to the reduction in intrinsic defects in the film (namely for ECWR powers 0, 100, and 200 W), but it is also partially due to the smaller grain size, which gradually decreases with increasing ECWR power and which negatively impacts carriers mobility.

As discussed in the preceding paragraphs, the Raman, PL, and CL spectra all confirm that the number of defects decreases as PECWR is increased (for ECWR powers 0, 100 and 200 W). These defects function as donors or acceptors57. Therefore, less defects translates to a decrease in the carrier density, lowering conductivity when the light is off consequently reducing the dark current. Similarly, the observation that the photocurrent decreases with increasing PECWR (approximately by one order of magnitude for every 100 W of PECWR) can be explained by the defects. Not only do the defects in the ZnO crystal act as donors and acceptors, but they also contribute to the absorption of the incident radiation, especially of lower-energy photons. Defects can create intermediate states in the band structure between the valence and conduction bands. These intermediate states can absorb light with lower energy (longer wavelengths) than what would normally be required for electron transitions from the valence to the conduction band. As a result, a higher number of defects increases the probability of electron and hole generation even at lower energies. Interestingly, the photosensitivity of the ZnO film deposited with PECWR of 300 W is lower compared to the photosensitivity of the film deposited with ECWR power of 200 W even though the dark current is smaller for the 300 W film. In fact, the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W exhibits the smallest dark current. The average free path of ZnO is several tens of nm58,59, which is similar to the average crystallite size calculated from the XRD spectra using the Scherrer formula. Therefore, the increase in grain boundaries due to the decrease in crystallite size have a large impact on the carrier lifetime and mobility32,58,59. As the crystallite size decreases, the number of carriers crossing grain boundaries increases, leading to a decrease in mobility. The film deposited with PECWR of 300 W has the smallest crystallite size (see Fig. 1e; Table 2) and therefore it exhibits the smallest dark current due to a significant decrease in carrier mobility. In this case, the lower photosensitivity of the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W is attributed to the decrease in photocurrent. Aside from decreasing carrier mobility in the dark, the increasing number of carriers crossing grain boundaries when illuminated as the crystallite size decreases also leads to an increase in grain boundary scattering and a reduction in carrier lifetime, lowering the photocurrent. As such, the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W exhibited not only the lowest dark current but also the lowest photocurrent. Note, however, that the low photocurrent has a dominant role in decreasing the overall photosensitivity of this film as it is reduced by two orders of magnitude compared to the film grown at PECWR of 200 W, while there is no significant change in the dark currents of the two films. Interestingly, even though the average crystallite size along the (002) orientation of the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W is similar to that of the film deposited at PECWR of 380 W, the photosensitivity of the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W is two orders of magnitude lower than that of the film deposited with PECWR of 380 W. This may be due to the smaller proportion of crystallites oriented along the (002) plane in the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W (see Fig. 1e; Table 2). Since the crystallites oriented along the (002) plane exhibit the largest average crystallite size compared to crystallites along the other orientations (see Table 2), the decrease in the proportion of these larger crystallites in the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W results to a smaller overall average crystallite size when including orientations other than (002). Therefore, the carrier lifetime and the photocurrent decreased the most in the 300 W film, resulting to a smaller photosensitivity for the film deposited with PECWR of 300 W film compared to the film deposited with PECWR of 380 W.

Overall, we can state that defects decrease significantly from 0 W to 200 W and slightly increase from 200 W to 380 W. Meanwhile, the grain size gradually decreases with increasing PECWR, reaching its smallest value at 300 W, where the deposition rate is at its maximum. Both of these trends ultimately result in the non-monotonic behavior of the photosensitivity dependence on ECWR power, as observed in Fig. 6c.

Time-resolved microwave conductivity (TRMC) technique was also utilized to elucidate the charge carrier dynamics in the ZnO films at the hundreds of nanosecond (ns) time scale. Using this method, transient photoconductivity, which is the product of yield (φ) and mobility (µ), is obtained and recombination behavior is monitored. Details of this technique can be found elsewhere60. Briefly, a ns pulsed laser is used to irradiate the sample which generates electron-hole pairs. These photogenerated charges modulate the photoconductivity of the material which is probed using X-band microwaves with frequency between 8 and 12 GHz. The change in the microwave power ΔP( ω,t)/P (\(\:{(P}_{w/\:light}-{P}_{w/o\:light})/{P}_{w/o\:light}\)) is proportional to the change in conductance (ΔG) from where the kinetics is extracted after rescaling it with the laser fluence (intensity and area, FA), the amount of light absorbed by the material (I0), elementary charge (e), and the ratio between the wide and small inner walls of the microwave guide (β), i.e., \(\:\phi\:\left({\mu\:}_{e}+{\mu\:}_{h}\right)={\Delta\:}G/{F}_{A}{I}_{0}e\beta\:\)61,62. This is analogous to the photosensitivity measurement discussed above (Eq. 1) but using a high frequency electric field (GHz) rather than a DC bias, and a ns pulsed laser instead of a deuterium lamp for photoexcitation. The laser pulse is then electronically delayed with respect to the GHz probe to provide the time window that displays the relaxation dynamics. To ensure that most, if not all, photoinduced species are mobile charges, a 360 nm (3.44 eV) pump is used for excitation, which is 70 meV above the band gap (3.37 eV). This means that there is at least 10 meV in excess of the exciton binding energy of the sample (60 meV) that would result to direct formation of dissociated electron-hole pairs, i.e., yield is close to unity (φ ~ 1), which allows plotting of ΔG in terms of mobility as shown in Fig. 7.

At PECWR = 0 W, the measured peak ΔG is 0.40 cm2/Vs while at PECWR = 100 W it increased to 4.03 cm2/Vs (Fig. 7a, see the inset for the plot of peak ΔG). This 10-fold improvement agrees with the increase in the measured photosensitivity of the device (Table 3) as the film becomes more photoconductive. In contrast, at PECWR = 200 W, the obtained peak ΔG diminished substantially to 0.04 cm2/Vs, a two orders of magnitude reduction.

From the Raman, PL, and CL spectroscopy data, the ZnO film grown at this PECWR of 200 W manifests much lower defects. This was also shown in the device wherein the dark current obtained is 9 orders of magnitude smaller than when PECWR is 0 W. For the TRMC results, this indicates that right after the laser pulse, photogenerated charge carriers immediately disappear such that before the GHz probe arrives after the first 8 ns (time resolution of the instrument) only few carriers are left. There are two scenarios that can explain this peculiar behaviour. The first scenario is when there are very high density of defects such that photogenerated charges immediately get trapped, substantially lowering the yield before the probe arrives. In the same situation, due to the prevalence of defect sites, mobility of carriers are likewise significantly reduced. The second scenario is when the photogenerated charges cannot find traps (defects) to fill up and instead recombine among themselves. This type of recombination is typically described as second-order, which is characterized by two exponential decays, and is strongly fluence dependent60,63. Plotted in Fig. 7b is the normalized ΔG of the films showing the decay of charges up to 900 ns. On the one hand, at PECWR 0 W and 100 W, a single exponential decay is enough to describe the trace, i.e., τ = 290 and 270 ns, respectively, alluding to its first-order trap-assisted recombination character. On the other hand, at PECWR 200 W, a two-exponential decay (τ1 = 36 ns, τ2 = 1390 ns) is necessary to appropriately mimic the kinetic trace. Moreover, this decay accelerates as the pump intensity is increased (Supplementary Fig. S12c) demonstrating that it is highly fluence dependent, a key feature of charge recombination that has second-order origin. Also shown in Supplementary Fig. S12(a-e) are fluence-dependent transient Δσ at different PECWR. At PECWR = 200 W the two-exponential decay is most evident. Although at PECWR 0 W and 300 W, (Supplementary Figs. S12a and S12d) the decay is somewhat fluence dependent, the effect is less and a single exponential decay is sufficient to depict the traces at some low fluences, details of which will be discussed below. Additionally, note that the lowest excitation fluence required to obtain a relatively decent signal-to-noise (S/N) in the ΔG kinetics for the film grown with PECWR of 200 W is 0.2 × 1012 ph/cm2. This is 10 times higher than the lowest fluences used for the rest of the samples having similar S/N. This denotes that it is not the limitation of the instrument that ΔG cannot be detected at fluences lower than 0.2 × 1012 ph/cm2, in fact for all other samples, decent S/N is obtained down to 0.02 × 1012 ph/cm2. Rather, this strongly suggests that it is the photophysics of the film itself that required the use of a high excitation fluence to obtain the ΔG. The necessity to pump this film at elevated fluence reinforces our claim that more charge carriers must be generated by the excitation in order to obtain a reasonable ΔG signal as a result of them immediately recombining brought about by the very low defect concentration. Hence, the two orders of reduction in ΔG obtained using TRMC in the ZnO film grown at the PECWR of 200 W is consistent with the Raman, PL, CL, and photosensitivity data exhibiting the lowest defects, almost mimicking intrinsic semiconductor behavior.

For PECWR of 300 W, the peak ΔG is 0.54 cm2/Vs and the decay at a fluence of 0.2 × 1012 ph/cm2 (see Supplementary Fig. S12d) was fitted by a single exponential (τ = 249 ns), implying trap-assisted recombination. This decay rate and mobility are lower than the film grown at PECWR of 100 W, which is 270 ns and 4.03 cm2/Vs, respectively. This signifies that the population of traps must have increased that shortens the lifetime and hinders the motion of charge carriers. While it is clear from the Raman spectra that the crystallinity increased, i.e., there are less crystalline defects, the GIXRD peaks and SEM images show reduction in the crystallite sizes. In such case, there are more grain boundaries where charge carriers can be trapped resulting to faster recombination rate and lower mobility. This supports the decreased photocurrent measured in the photodetector device. However, it is noteworthy that at fluences higher than 0.2 × 1012 ph/cm2 the decays accelerate (see Supplementary Fig. S12d) and require bi-exponential fitting. This indicates that second-order recombination starts to play a role, suggesting that at elevated fluences, traps are already filled such that any excess photogenerated charge carriers begin to find each other and recombine. In other words, while there is an increase in grain boundaries due to small crystallite sizes that trap charge carriers, which lower mobility and shorten the lifetime, this increase is not substantial as they are easily filled at high fluences. This is in accordance with the very low dark current obtained in the device.

For PECWR of 380 W, both the mobility (0.55 cm2/Vs) and lifetime (τ = 251 ns) are very similar to the film grown at PECWR of 300 W. Despite this, its decay dynamics is fluence independent and was fitted by a single exponential where trap-assisted recombination is the main relaxation mechanism. This means that even at higher fluences, traps are not fully filled suggesting that defect concentration is higher. This is in agreement with the measurement in the device wherein the dark current obtained from the film grown at PECWR of 380 W is higher than that from the film grown at PECWR of 300 W.

These results demonstrate that ZnO films can be used as photoconductive detectors of VUV radiation, but the photosensitivity is highly dependent on the amount of intrinstic defects and crystallinity of the films. A large number of defects leads to a high dark current, which could make the films almost non-photosensitive as in the case of the film deposited with PECWR of 0 W (MF only deposition). Increasing PECWR to 200 W or more decreases significantly the number of defects, causing the films to become photosensitive. In the case of photosensitive films, the size of the crystallites play an important role in their photosensitivity. Small crystallites increase grain boundaries, which lead to a decrease in carrier mobility and low dark current, but at the same time also lead to a decrease in carrier lifetime and low photocurrent. The photosensitivity is ultimately determined by the ratio of the photocurrent to the dark current and the crystallinity of the film. The films deposited at PECWR of 300 W and 380 W have poorer crystallinity compared to the film deposited at PECWR of 200 W, exhibited by the less intense UV emission of the films in their PL and CL spectra (see Fig. 5). The poor crystallinity and smaller crystallite size are attributed to the increase in deposition rate and re-sputtering associated with the increase in plasma density at the higher ECWR powers. ZnO films with less defects, large crystallite sizes and good crystallinity, such as that achieved in the film deposited with PECWR of 200 W, have ideally high photosensitivity. Therefore, the ability to control the amount of defects and crystalline characteristics of the films plays an important role when developing a photosensitive VUV photodetector. The MF + ECWR deposition technique has the advantage of easily controlling the amount of defects and the crystallinity of ZnO films by adjusting the ECWR power.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the successful deposition of ZnO thin films on soda-lime glass substrates using the MF + ECWR technique with varying ECWR powers ranging from 0 W to 380 W. By controlling the ECWR power, we were able to systematically manipulate the defect concentration and crystallinity of the films, which in turn significantly influenced their photoconductive properties in the VUV region. At an optimal ECWR power of 200 W, the ZnO films exhibited a remarkable increase in photosensitivity by eight orders of magnitude, primarily due to a drastic reduction in dark current. This reduction was linked to a substantial decrease in intrinsic defects, as confirmed by Raman spectroscopy, photoluminescence (PL), and cathodoluminescence (CL). However, increasing the ECWR power beyond 200 W led to a reduction in photocurrent, attributed to the formation of smaller crystallites and the corresponding increase in grain boundaries, which shortened the carrier lifetime. Time-Resolved Microwave Conductivity (TRMC) measurements further supported these findings, showing that the films deposited at PECWR of 200 W had very low trap densities, leading to fast carrier recombination and lower photoconductivity in the ns time scale. This behavior, indicative of second-order recombination, contrasts with the trap-assisted recombination observed in films deposited at lower ECWR powers (0 W and 100 W), where higher defect concentrations allowed for longer carrier lifetimes. The TRMC results revealed that at PECWR of 300 W and 380 W, while the films exhibited lower dark currents due to the increased grain boundaries, their mobility and photoconductivity were reduced due to faster recombination at grain boundaries. Overall, this study highlights the critical role of ECWR power in optimizing ZnO thin films for VUV photoconductive applications. Films deposited at PECWR of 200 W offer the best compromise between low dark current and high photocurrent, making them highly suitable for sensitive VUV detection. Further tuning of deposition parameters, informed by techniques such as TRMC, could lead to even more refined control over defect management and charge carrier dynamics.

Experimental methods

All ZnO layers were prepared using the same technology described in detail in Ref.42. The deposition experiments were carried out in an ultra-high vacuum (UHV) stainless steel chamber with a total volume of 30 dm3, using a hybrid MF + ECWR deposition system. Soda-lime glass (SLG) slides from Menzel-Gläser, Thermo Scientific, Braunschweig, Germany, with size 20 mm × 20 mm × 1 mm were used as substrates. Prior to deposition, the chamber was continuously pumped by a turbo-molecular and a rotary vane pump to a base pressure of 1 × 10–4 Pa and during deposition the pressure was maintained at a constant value 0.3 Pa. Argon and oxygen gas flows were controlled through gas flow controllers, set to QAr = 10 sccm and QO2 = 10 sccm for all experiments. The substrate was mounted on a rotating holder, spinning at 3 rpm, maintaining a 10 cm distance between the target and the substrate. The substrates were heated to 300 °C during deposition using a series of Kanlux J-1000 W 189MM halogen lamps and the temperature was monitored by a pair of static thermocouples. The error in temperature determination can be 15 to 20%. After deposition the samples were left unannealed.

The deposition system included a 2-inch magnetron with circular planar cathodes of 50 mm diameter. The target, 3 mm thick, was made of pure zinc with a purity of 99.9% (Plasmaterial). The magnetron was connected to a bipolar pulse power supply operating at a medium frequency of 40 kHz. The total absorbed MF power in all experiments was 300 W. A water-cooled RF ICP coil with a 200 mm diameter was placed between the magnetrons and the substrates. A PECWR power of 0, 100, 200, 300 and 380 W was applied to the ICP coil and maintained constant during the deposition process. A static homogeneous magnetic field with an induction of approximately 1.7 mT was introduced into the ECWR electrode region using a Helmholtz coil to bring the system in ECWR resonance. The total deposition times were 55 min for sample 1 (pure MF) and 25 min for all other samples (MF + ECWR). A comprehensive overview of the deposition conditions is provided in Table 4.

The XRD spectra of the films are measured using an Empyrean x-ray diffractometer that utilizes Cu Kα radiation with a wavelength of 0.154 nm. The 2θ range is 0o to 90o and the step size is 0.01o. The diffraction spectra are analyzed using a curve fitting and peak fitting software (Fityk). The surface morphology of the films is imaged using a low acceleration voltage field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, model JSM-7800 F, JEOL Ltd.) with an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. The FE-SEM is operated at room temperature. The surface of the samples are coated with a conductive coating (Os coating) with a thickness of 3 nm. The image obtained is the secondary electron image. The Raman spectra are obtained using the polarized beam of an Ar ion laser operating at 514.5 nm wavelength (Renishaw Raman Microscope RM 1000) in the back-scattering configuration. The total area illuminated by the laser beam is 4 µm2. The PL spectra are obtained by exciting the films with 290 nm light from a wavelength tunable 100 femtosecond pulsed laser system (PHAROS, Orpheus, Orpheus-F, LIGHT CONVERSION, Lithuania) with a repetition rate of 20 kHz. The PL emission is collected by a quartz lens and focused onto a fiber spectrometer (StellarNet UV) with a 1200 g/mm grating efficiency from 200 nm to 600 nm. The CL spectra are obtained using the FE-SEM used for obtaining the surface morphology, but is equipped with a CL detector (Gatan MonoCL4Elite). The measurement is performed with an accelerating voltage was 5 kV and at room temperature. For photoconductivity measurements, a pair of interdigitated Al electrodes is deposited on the films by vacuum deposition. The films are then excited by a deuterium lamp (L10366 series, Hamamatsu Photonics K. K.) emitting from about 115 nm to 170 nm (VUV wavelengths) with a central dominant peak at 160 nm. The currents are measured using a pico ammeter (Model 6487 Picoammeter/Voltage source, KEITHLEY), which also provided the bias voltage.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14847883.

References

Pile, D. F. P. Vacuum-ultraviolet source. Nat. Photonics 12, 568 (2018).

Yamanoi, K. et al. Luminescence properties of Nd3+ and Er3+ doped glasses in the VUV region. Opt. Mater. 35, 1962 (2013).

Shimizu, T. et al. Self-sensing paper-based actuators employing ferromagnetic nanoparticles and graphite. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 14 (2017).

Arita, R. et al. Significant blue-shift in photoluminescence excitation spectra of Nd3+:LaF3 potential laser medium at low-temperature. Opt. Mater. 47, 462 (2015).

BenMoussa, A. et al. Pre-flight calibration of LYRA, the solar VUV radiometer on board PROBA2. Astron. Astrophys. 508, 1085 (2009).

Torr, M. R. et al. A far ultraviolet imager for the International Solar-Terrestrial Physics Mission. Space Sci. Rev. 71, 329 (1995).

Shea, M. A., Smart, D. F., McCracken, K. G., Dreschhoff, G. A. M. & Spence, H. E. Solar proton events for 450 years: the Carrington event in perspective. Adv. Space Res. 38, 232 (2006).

Mahkov, V. Vacuum ultraviolet luminescence of wide band-gap solids studied using time-resolved spectroscopy with synchrotron radiation. Phys. Scr. 89, 044010 (2014).

Minami, Y. et al. Spectroscopic investigation of praseodymium and cerium co-doped 20Al (PO3) 3-80LiF glass for potential scintillator applications. J. Non-Cryst Sol 521, 119495 (2019).

Nakazato, T. et al. Nd3+: LaF3 as a step-wise excited scintillator for femtosecond ultraviolet pulses. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 57, 1208 (2010).

Dujardin, C. et al. Needs, trends, and advances in inorganic scintillators. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 65, 1977 (2018).

Arikawa, Y. et al. Note: Light output enhanced fast response and low afterglow L6i glass scintillator as potential down-scattered neutron diagnostics for inertial confinement fusion. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 81, 10 (2010).

Pearton, S. J., Zopler, J. C., Shul, R. J. & Ren, F. Radial plasma flow in a hot anode vacuum arc. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 114 (1999).

Li, J. & Fan, Z. Y. 200nm deep ultraviolet photodetectors based on AlN. Appl. Phys. Lett. 89, 213510 (2006).

Zheng, W., Huang, F., Zheng, R. & Wu, H. Low‐dimensional structure vacuum‐ultraviolet‐sensitive (λ < 200 nm) photodetector with fast‐response speed based on high‐quality AlN micro/nanowire. Adv. Mater. 27, 3921 (2015).

Cadatal-Raduban, M. et al. Effect of substrate and thickness on the photoconductivity of nanoparticle titanium dioxide thin film vacuum ultraviolet photoconductive detector. Nanomaterials 12,10 (2022).

Cadatal-Raduban, M., Pope, J., Olejníček, J., Kohout, M. & Harrison, J. A. S.M.R. Hasan. Ultraviolet-C photoresponsivity using fabricated TiO2 thin films and transimpedance-amplifier-based test setup. Sensors 22, 8176 (2022).

Cadatal-Raduban, M. et al. Titanium dioxide thin films as vacuum ultraviolet photoconductive detectors with enhanced photoconductivity by gamma-ray irradiation. Thin Solid Films 726, 138637 (2021).

Zheng, W. et al. Vacuum ultraviolet photodetection in two-dimensional oxides. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 20696 (2018).

Shaikh, S. K., Inamdar, S. I., Ganbavle, V. V. & Rajpure, K. Y. Chemical bath deposited ZnO thin film based UV photoconductive detector. J. Alloys Comp. 664, 242 (2016).

Balducci, A. et al. Extreme ultraviolet single-crystal diamond detectors by chemical vapor deposition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 193509 (2005).

Uchida, K., Ishihara, H., Nippashi, K., Matsuoka, M. & Hayashi, K. Measurement of vacuum ultraviolet radiation with diamond photo sensors. J. Light Vis. Eng. 28, 97 (2004).

Lin, C. N. et al. Diamond‐based all‐carbon photodetectors for solar‐blind imaging. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6, 1800068 (2018).

Zhang, W. J., Chong, Y. M., Bello, I. & Lee, S. T. Nucleation, growth and characterization of cubic boron nitride (cBN) films. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 40, 6159 (2007).

Samantaray, C. B. & Singh, R. N. Review of synthesis and properties of cubic boron nitride (c-BN) thin films. Int. Mater. Rev. 50, 313 (2005).

Li, Y., Guo, J., Zheng, W. & Huang, F. Amorphous boron nitride for vacuum-ultraviolet photodetection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 023504 (2020).

Zheng, W., Lin, R., Zhang, Z. & Huang, F. Vacuum-ultraviolet photodetection in few-layered h-BN. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 27116 (2018).

Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., Niiyama, T., Miya, K. & Taniguchi, M. Far-ultraviolet plane-emission handheld device based on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Photonics 3, 591 (2009).

Kato, T., Cadatal-Raduban, M., Horiuchi, Y., Ozawa, G. & Ono, S. Influence of annealing on thin film/substrate interface and vacuum ultraviolet photoconductivity of neodymium fluoride thin films. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 11, 2300696 (2024).

Kato, T., Cadatal-Raduban, M. & Ono, S. Towards the development of a self-powered vacuum ultraviolet photodetector based on calcium fluoride/gold interface. Results Opt. 11, 100378 (2023).

Yu, X., Cadatal-Raduban, M., Kato, S., Kase, M. & Ono, S. Femtosecond PLD-grown YF3 nanoparticle thin films as improved filterless VUV photoconductive detectors. Nanotechnology 32, 015501 (2020).

Yu, X. et al. Filterless tunable photoconductive ultraviolet radiation detector using CeF3 thin films grown by pulsed laser deposition. AIP Adv. 10, 4 (2020).

Suzuki, K., Cadatal-Raduban, M., Kase, M. & Ono, S. Band gap engineering of CaxSr1-xF2 and its application as filterless vacuum ultraviolet photodetectors with controllable spectral responses. Opt. Mater. 88, 576 (2019).

Ieda, M. et al. Optical characteristic improvement of neodymium-doped lanthanum fluoride thin films grown by pulsed laser deposition for vacuum ultraviolet application. Jpn J. Appl. Phys. 51, 022603 (2012).

Shan, W. et al. Nature of room-temperature photoluminescence in ZnO. Appl. Phys. Lett. 86, 191911 (2005).

Hacini, N. et al. Compositional, structural, morphological, and optical properties of ZnO thin films prepared by PECVD technique. Coatings 11, 202 (2021).

Franklin, J. B. et al. Optimised pulsed laser deposition of ZnO thin films on transparent conducting substrates. J. Mater. Chem. 21, 8178 (2011).

Mahmood, K. & Samaa, B. M. Influence of annealing treatment on structural, optical, electric, and thermoelectric properties of MBE-grown ZnO. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 126, 766–771 (2018).

Bing-chu, Y., Xiao-yan, L., Fei, G. & Xue-long, M. Photoluminescence properties of ZnO thin films prepared by DC magnetron sputtering. J. Cent. South. Univ. Technol. 15, 449–453 (2008).

Kermiche, F., Taabouche, A., Bouabellou, A., Hanini, F. & Bouachiba, Y. Behavior study of ZnO thin films grown by PLD for several applications. Cryst. Rep. 67, 1239–1245 (2022).

Miandal, K. et al. Photoelectrochemical activity of magnetron sputtered ZnO thin films: role of thermal annealing. J. Adv. Res. Mater. Sci. 20, 6–13 (2016).

Cadatal-Raduban, M. et al. Ultrafast UV luminescence of ZnO films: sub‐30 ps decay time with suppressed visible component. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 2400377 (2024).

Jousten, K. Handbook of Vacuum Technology (Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co, 2016).

Monica, M. C., Allain, D. B., Hayden, D. R. & Juliano, D. N. Characterization of magnetron-sputtered partially ionized deposition as a function of metal and gas species. J. Vac Sci. Technol. A 18, 797–801 (2000).

Green, K. M., Hayden, D. B., Juliano, D. R. & Ruzic, D. N. Determination of flux ionization fraction using a quartz crystal microbalance and a gridded energy analyzer in an ionized magnetron sputtering system. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68, 4555–4560 (1997).

Anders, A. Deposition rates of high power impulse magnetron sputtering: physics and economics. J. Vac Sci. Technol. A 28, 783–790 (2010).

Brenning, N. et al. A unified treatment of self-sputtering, process gas recycling, and runaway for high power impulse sputtering magnetrons. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol., 26, 125003 (2017).

Lundin, D., Minea, T. & Gudmundsson, J. T. High Power Impulse Magnetron Sputtering 49–80. (Elsevier, 2020).

Kelly, P. J. et al. Deposition of photocatalytic titania coatings on polymeric substrates by HiPIMS. Vacuum, 86, 1880–1882 (2012).

Poolcharuansin, P., Bowes, M., Petty, T. J. & Bradley, J. W. Ionized metal flux fraction measurements in HiPIMS discharges. J. Phys. Appl. Phys., 45, 322001 (2012).

Kubart, T., Čada, M., Lundin, D. & Hubička, Z. Investigation of ionized metal flux fraction in HiPIMS discharges with Ti and Ni targets. Surf. Coat. Technol., 238, 152–157 (2014).

Montenegro, D. N. et al. Non-radiative recombination centres in catalyst-free ZnO nanorods grown by atmospheric-metal organic chemical vapour deposition. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 46, 235302 (2013).

Song, Y. et al. Raman spectra and microstructure of zinc oxide irradiated with swift heavy ion. Crystals 9, 395 (2019).

Sann, J. et al. Zn interstitial related donors in ammonia-treated ZnO powders. Phys. Rev. B 76, 195203 (2007).

Pelant, I. & Valenta, J. Non-radiative Recombination, Luminescence Spectroscopy of Semiconductors (Oxford Academic, 2012).

Sezemsky, P. et al. Modified high frequency probe approach for diagnostics of highly reactive plasma. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 28, 115009 (2019).

Bandopadhyay, K. & Mitra, J. Zn interstitials and O vacancies responsible for n-type ZnO: what do the emission spectra reveal?. RSC Adv. 5, 23540 (2015).

Baxter, J. B. & Schmuttenmaer, C. A. Conductivity of ZnO nanowires, nanoparticles, and thin films using time-resolved terahertz spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 25229 (2006).

Gan, Z., Ahn, S., Yu, H., Smith, D. J. & McCartney, M. R. Mater. Res. Exp. 2, 10 (2015).

Fravventura, M. C., Deligiannis, D., Schins, J. M., Siebbeles, L. D. A. & Savenije, T. J. What limits photoconductance in anatase TiO2 nanostructures? A real and imaginary microwave conductance study. J. Phys. Chem. C, 117, 8032 (2013).

Caselli, V. M. & Savenije, T. J. Quantifying charge carrier recombination losses in MAPbI3/C60 and MAPbI3/Spiro-OMeTAD with and without bias illumination. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 7523 (2022).

Savenije, T. J., Guo, D., Caselli, V. M. & Hutter, E. M. Adv. Energy Mat. 1903788 (2020).

Hutter, E. M. & Savenije, T. J. Thermally activated second-order recombination hints toward indirect recombination in fully inorganic CsPbI3Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 2068 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Czech Academy of Sciences (MPP project no. JSPS-23-07), the JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 21K18909, the JSPS Bilateral Program Grant Number JPJSBP120232502, the Amada Foundation (Grant No. AF-2022230-B3) and Hibi Science Foundation, the Catalyst: Seeding fund provided by the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment and administered by the Royal Society Te Apārangi (CSG-MAU2003), by Operational Programme Johannes Amos Comenius financed by European Structural and Investment Funds and the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (Project No. SENDISO -CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004596), by the Osaka University Institute of Laser Engineering Collaborative Research Fund (2024B1-004) and by the Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences (KFAS - project grants PN2335EE1857 and CN2215SC1583). The authors would like to thank Dr. Yoko Sakurai from the Nagoya Institute of Technology for her help in SEM and CL measurements and to Prof. Tom Savenije of Delft University of Technology where TRMC data were obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H., Y.M.: investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft, visualization. J.O., M.C.-R.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, discussion of results, writing original draft, visualization, project administration, funding acquisition. K.Y.: investigation, discussion of results, resources, writing-review and editing, project administration, funding acquisition, supervision. C.S.P.Jr, A.S.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, discussion of results, writing-original draft, visualization. A.P., M.K., M.C., A.K., Y.A.: investigation, formal analysis, discussion of results, writing-review and editing. N.S.: resources, supervision, writing-review and editing. Z.H., S.O.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, discussion of results, resources, writing-review and editing, supervision. All authors discussed and commented on the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hibino, K., Olejníček, J., Yamanoi, K. et al. Impact of electron cyclotron wave resonance plasma on defect reduction in ZnO thin films. Sci Rep 15, 5555 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88921-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88921-5