Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) poses a formidable challenge to global health, necessitating the quest for novel biomarkers to improve therapeutic strategies. This study explores ABCE1 (ATP-binding cassette subfamily E member 1) as a potential biomarker for CRC and delves into its intricate molecular mechanisms. Through integrated bioinformatic analyses, this study underscores the significant oncogenic role of ABCE1 in CRC, opening new avenues for promising therapeutic interventions. Deletion of ABCE1 reduced cell growth, abrogated aerobic glycolysis, and promoted apoptosis in HT-29 and HCT-116 cells. Further validation through experimentation with irinotecan revealed compelling outcomes, including diminished cell growth, induces G1 phase cell cycle arrest, and promotes apoptosis in HCT-116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. ABCE1 KO with irinotecan combined treatment significantly increased the inhibition of cell proliferation and aerobic glycolysis in CRC cells, accentuating the multifaceted role of ABCE1 in CRC progression. Moreover, this work also demonstrated the complex relationship between ABCE1 and the p53 signalling pathway, which was confirmed in experimental assays. These assays also revealed that deletion of ABCE1 with irinotecan might regulate G1 phase cell cycle arrest, inhibit metabolic regulation, and activate the p53 pathway to induce apoptosis in HCT-116 cells. Molecular docking analyses further supported these findings, revealing the strong binding affinity of irinotecan for targets of the p53 signalling cascade. Collectively, these comprehensive insights support the potential therapeutic efficacy of targeting ABCE1 in CRC treatment strategies. Overall, the findings from this study underscore the importance of ABCE1 as a potential biomarker in CRC and illuminate its complex molecular mechanisms. The demonstrated effectiveness of ABCE1 inhibition, particularly through irinotecan, coupled with its interplay with crucial signalling pathways such as p53, highlights its potential as a promising therapeutic option for colorectal cancer treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer, encompassing malignancies originating in the colon or rectum, constitutes a substantial global health burden1. The genesis of this condition, which usually starts as adenomatous polyps that progressively develop into malignant growths, is a complicated interaction between hereditary predisposition and environmental variables. Its incidence increases with age, and various risk factors, including family history, inflammatory bowel diseases, and lifestyle choices, such as diet and smoking, contribute to its development. The clinical presentation varies widely, with symptoms ranging from subtle changes in bowel habits to overt rectal bleeding and abdominal discomfort2. Crucially, early-stage disease may often be asymptomatic, underscoring the critical importance of regular screening initiatives. Diagnosis relies on a combination of screening tests such as colonoscopy, imaging studies, and biopsy for confirmation3. Based on patient characteristics and cancer stage, several treatment techniques, including radiation therapy, chemotherapy, surgery, and targeted treatments, are used. Prognosis hinges on timely detection and intervention, with early-stage cancers resulting in significantly better outcomes. Prevention strategies help for lifestyle modifications and adherence to screening guidelines4.

The current paradigm for treating colorectal cancer involves a multidisciplinary approach that is usually customized based on the disease’s stage and particular features. Surgical resection remains a cornerstone, particularly for localized tumours, yet it may not always be feasible for advanced or metastatic cases due to anatomical constraints or patient comorbidities5. Chemotherapy, often combined with surgery or used as adjuvant therapy, targets rapidly dividing cancer cells but is associated with significant side effects and the potential for drug resistance6,7. Targeted therapies, such as anti-EGFR or anti-VEGF antibodies, offer precision by inhibiting specific molecular pathways involved in cancer growth, but their efficacy may be limited by the absence of targetable mutations or the development of resistance8,9,10. Clinical trials offer hope for innovative treatments, but their accessibility and potential risks must be considered. Although these strategies have advanced treatment outcomes, their limitations underscore the ongoing need for research and development to refine existing approaches and explore new therapeutic avenues.

Molecular targeted therapy has revolutionized the landscape of cancer treatment, including that of colorectal cancer, by offering highly specific interventions aimed at disrupting key molecular pathways driving tumorigenesis11. To reduce systemic toxicity, these treatments are designed to specifically target certain molecules or biological processes that are aberrantly triggered in cancer cells while leaving normal cells unaffected. Anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab disrupt EGFR signalling, which prevents the growth of cancer cells and promotes their death12. One of the primary advantages of molecular targeted therapies is their precision, which allows for more effective tumour eradication with fewer adverse effects than conventional chemotherapy13. Additionally, the advent of targeted medicines has increased the number of therapeutic choices accessible, especially for patients with metastatic or advanced colorectal cancer, who may not have access to many other medications. Despite these advantages, challenges such as the emergence of resistance mechanisms and the need for reliable predictive biomarkers for treatment response remain areas of active research14. Nonetheless, molecular targeted therapies represent a cornerstone of modern oncology, offering hope for improved outcomes and quality of life for patients with colorectal cancer. In the realm of cancer research, the correlation of biomarkers identified through bioinformatic analysis holds profound importance for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment strategies. Bioinformatics facilitates the discovery and analysis of several biomarkers, including gene expression patterns, epigenetic alterations, genetic mutations, and protein signatures, linked to distinct forms of cancer through the use of advanced computer algorithms and statistical models15.

ABCE1, often referred to as ATP-binding cassette subfamily E member 1, is an essential component of several biological activities, such as ribosome synthesis, translation initiation, and mRNA decay16. The role of ABCE1 in translational process involves its ability to control protein synthesis, which could influence tumour growth and progression17. ABCE1 participates in ribosome biogenesis, the process by which ribosomes, the cellular machinery responsible for protein synthesis, are assembled. The onset and spread of cancer are linked to aberrant ribosome biosynthesis18. Dysregulated expression or activity of ABCE1 may impact ribosome biogenesis, thereby influencing protein synthesis and cellular proliferation in cancer cells. Through the modulation of the amounts of particular mRNA transcripts, ABCE1 contributes to the maintenance of cellular homeostasis through the regulation of mRNA decay19. Dysregulation of mRNA decay pathways can contribute to tumorigenesis by altering the expression of genes involved in survival and metastasis. According to a previous study, the abnormal expression of the ABCE1 gene in human lung adenocarcinoma and its effect on lung cancer cell proliferation revealed that ABCE1-specific shRNA inhibits A549 cell growth20. Studies have reported dysregulated expression of ABCE1 in various cancer types, including breast, lung, colorectal, and prostate cancers. It is possible that ABCE1 might be used as a biomarker for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, or therapeutic targeting because changes in its expression levels have been linked to clinicopathological characteristics and patient prognosis in several tumours21,22. Through the use of a wide range of bioinformatics studies, the aim of this study was to determine the oncogenic function of ABCE1 in the development of colorectal cancer. The work was also intended to clarify how ABCE1 is related to prognostic markers such as mRNA expression, DNA methylation patterns, mutations, and immunological infiltration. Additionally, this study delves into the therapeutic potential of irinotecan, a drug used for colorectal cancer treatment and the deletion of ABCE1, which are known to reduce colorectal cancer cell growth, regulate metabolic dysfunctions, induce G1 phase cell cycle arrest, and promotes apoptosis specifically in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. Furthermore, to corroborate the bioinformatic findings regarding the prediction of the involvement of the p53 signalling pathway, experimental validation was conducted through assessments of cell cycle progression, apoptotic rates, and gene expression levels by RT‒PCR in HCT-116 cells.

Results

ABCE1 upregulation in COAD datasets

The flow chart of the study is shown in Fig. 1. Using bioinformatic analysis of datasets related to colorectal cancer, early work was performed to examine the expression profile of the ABCE1 gene. Initially, ABCE1 mRNA expression was examined for its pan-cancer status using the UALCAN, GEPIA, and TIMER databases. As shown in Fig. 2 (A-C), ABCE1 was significantly upregulated across various cancers, including breast, lung, liver, and colorectal cancers. Figure 2D shows the comparison of ABCE1 expression between normal (n = 275) and tumour samples (n = 349) in the COAD datasets, revealing the upregulation of ABCE1. Additionally, through analysis of GDC datasets, clinical factors and vital status, as well as data types such as clinical, single-nucleotide variant (SNV), biospecimen, and copy number variant (CNV) data, revealed significant upregulation and high mutation frequency in ABCE1, as shown in Fig. 2E. Furthermore, the heatmap visualization in Fig. 2F highlights the association of ABCE1 with high expression in colorectal cancer tissue samples compared with healthy tissues. Overall, our early bioinformatic studies point to a potential oncogenic function for ABCE1 in the development of colorectal cancer.

The mRNA expression of ABCE1 among various cancers. (A-C) Expression levels of ABCE1 in different cancer types from TCGA datasets from UALCAN, TIMER and GEPIA databases. The graphs were represented in box plot, x-axis denotes the different types of cancer, and y-axis denotes the expression level (log2 [TPM]). The cancer expression levels were compared between normal (blue color) and tumour cancer samples (red color). (D) GEPIA datasets represents the pan-cancer view and highlighted particularly COAD datasets of ABCE1 expression. (E) GDC datasets represents the heatmap using TCGA datasets by clinical characteristics (Race, age at diagnosis, vital status, and Days to death) and data types (clinical, biospecimen, sequencing reads, SNV, CNV, and transcriptome profiling) of COAD samples. It denotes the mutation frequency and list of genes (y-axis) associated with ABCE1 in COAD datasets. (F) The heat map illustration denotes the expression levels of ABCE1 in TCGA-COAD datasets. The expression levels were denoted from low (normal) to high (high) by blue to red color. ABCE1 expression results among various cancers were displayed as histogram and color images are available online. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TIMER, Tumour Immune Estimation Resource; TPM, Transcript Per Million; GDC, Genomic Data Commons; COAD, Colon Adenocarcinoma; SNV, Single Nucleotide Variant; CNV, Copy Number Variant.

ABCE1 mRNA expression and protein status in the COAD datasets

Using the GSE database, we performed a thorough study of gene expression patterns in colorectal cancer based on preliminary findings. Significant gene regulation in pathways linked to colorectal cancer and cancer was found in analyses using GSEA software. These findings suggest that ABCE1 overexpression is associated with colorectal cancer datasets, as shown in Fig. 3A and B. Dysregulation of alternative splicing, as well as exon and junction expression profiles, can contribute to cancer development and progression23. We also analysed the exon, junction, and isoform expression profiles of ABCE1, which were significantly correlated with altered function in colon datasets, as depicted in Fig. 3C-E. The UALCAN and GEPIA databases were utilized to investigate the expression levels of ABCE1 mRNA in both advanced and early stages of colorectal cancer. The results revealed a noteworthy elevation in advanced stages as opposed to early stages in the tissue samples of patients with colorectal cancer, as depicted in Fig. 3F and G. Additionally, the oncogenic role of ABCE1 was found to affect mostly the 41–60-year age group of patients with colorectal cancer, as shown in Fig. 3H.

The mRNA expression levels of ABCE1 in COAD datasets. (A, B) The GSEA plot from GSE33113 datasets indicates the upregulation of ABCE1 from KEGG pathways denotes highly involved in Pathways in cancer (NES-1.12) and colorectal cancer (NES-1.22). The green line indicates the NES and red color to blue color mentions the tumour (positively correlated) and normal (negatively correlated) from COAD datasets. The bar code represents each gene involved in expression levels in COAD datasets. (C-D) Bioinformatic analysis mentioned the exon, Junction, and Isoform expression level of ABCE1 from HGNC datasets among various cancers, in colon, ABCE1 has highlighted. (F) mRNA expression levels of ABCE1 in COAD datasets from UALCAN in various stages (Stage I (n = 45), II (n = 110), III (n = 80), and IV (n = 39) compared to normal (n = 41) colon tissues from TCGA clinical samples. Moreover, (G) GEPIA datasets also shows high elevation of advanced stage mRNA expression (F value = 2.95) compared to an early stage from COAD datasets. (H) ABCE1 expression levels in different age groups (21–100) compared with normal (n = 41) colon tissues were also visualized using UALCAN database. (I) To find the prognostic value of ABCE1 in COAD datasets, nodal metastasis (N0 (n = 166); N1 (n = 70); N2 (n = 47)) for ABCE1 from TCGA datasets. (J) The overall survival of ABCE1 from COAD datasets were retrieved from GEPIA database and visualized by Kaplan-Meier plotter. The red color mentioned the high ABCE1 and blue color denotes the low ABCE1 expression. (K) The protein expression levels of ABCE1 from CPTAC samples of COAD datasets shows high expression level (n = 97) compared with normal (n = 100). (L) The protein expression levels of ABCE1 were visualized by immunoblot in normal colon mucosa, NCM-460 and colorectal cancer cells, HCT-116 and HT-29. β-actin as an internal control. (M) ABCE1 mRNA expression levels between control (n = 41) and tumour samples (n = 286) were monitored using TCGA-COAD datasets. (N) The gene expression of ABCE1 by qRT-PCR was examined in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001. Uncropped western blot images corresponding to Fig. 2 can be found in Supplementary Fig. 4a. GSEA, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; NES, Normalized Enrichment Score; HGNC, HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee; CPTAC, Clinical Proteomic Tumour Analysis Consortium; RT-PCR, Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Metastasis, a hallmark of cancer, was also examined using the UALCAN database, which revealed significant upregulation of ABCE1 expression in patients with N2-stage colorectal cancer, as depicted in Fig. 3I. The predictive significance of ABCE1 in colorectal cancer was evaluated using overall survival plots generated from the GEPIA database. As shown in Fig. 3J, increased ABCE1 expression was linked to low survival rates in colorectal cancer tissue samples. Figure 3K shows an increase in ABCE1 protein expression in tumour samples relative to normal colon samples according to the CPTAC data. Western blotting analysis of the expression of the ABCE1 protein in colon tumour cell lines (HCT-116 and HT-29) and normal colon mucosa (NCM-460) cell lines revealed that the protein expression levels were greater in the tumour cells than in the normal colon mucosa, as shown in Fig. 3L. Analysis of TCGA datasets of colon cancer clinical samples further confirmed the upregulation of ABCE1 mRNA expression in tumour samples compared with healthy colon tissue samples, as shown in Fig. 3M. Furthermore, gene expression patterns in colorectal cancer cells were analysed by qRT‒PCR to confirm the bioinformatic predictions, which revealed an increased ABCE1 expression in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells (Fig. 3N). Taken together, the findings of ABCE clearly imply that ABCE1 may be carcinogenic in the development of colorectal cancer.

ABCE1 survival profiles

To validate the oncogenic role of ABCE1 in colorectal cancer, we investigated its prognostic value in survival profiles using KM plots derived from COAD datasets. The overall survival plot based on early and advanced stages of ABCE1 expression was generated using Kaplan‒Meier analysis. The results depicted in Fig. 4A clearly illustrate those patients with high ABCE1 expression in advanced stages (stage III – HR-1.91; stage IV – HR-3.23) of colorectal cancer exhibited poor overall survival (OS) rates compared with those in early stages (stage I – HR-0.48; stage II – HR-0.77) of the disease. Similarly, ABCE1 expression in disease-free survival (DFS) analysis of colorectal cancer patients revealed that those with low ABCE1 expression in advanced stages (stage III, HR = 0.51; stage IV, HR = 0.23) had higher survival rates than those with low ABCE1 expression in early stages (stage I, HR = 0.76; stage II, HR = 0.57), as shown in Fig. 4B. These findings clearly imply that ABCE1 could function as an oncogene and might be a potential target for the development of colorectal cancer.

Survival status of ABCE1 in colon adenocarcinoma datasets. (A) The overall survival (OS) plots of ABCE1 expression in early (Stage I and II) and advanced (Stage III and IV) stages were monitored using KM plot. (B) The Disease-Free Survival plots by Kaplan-Meier method indicates the survival rate (%) of ABCE1 in early (Stage I and II) and advanced (Stage III and IV) stages from TCGA datasets. Red color indicates the ABCE1 high expression with poor survival and red color denotes the ABCE1 low expression with prolonged survival rate. The x-axis denotes the time (months) and y-axis denotes the survival probability.

DNA methylation status of ABCE1 in COAD

Further, compared to the expression levels of ABCE1 in primary tumours with those in normal colon tissues to investigate the possible function of ABCE1 in DNA methylation dynamics in colorectal cancer, as shown in Fig. 5A. The results of this investigation revealed that ABCE1 expression was upregulated in primary tumours, indicating that ABCE1 is involved in the development of colorectal cancer. In addition, we investigated the relationships between promoter methylation levels and ABCE1 expression and overall survival rates in clinical samples from patients with colorectal cancer. Figure 5B shows that poor survival is linked to increased expression of ABCE1, suggesting that ABCE1 may have prognostic value in colorectal cancer. We also examined the relationship between methylation status and ABCE1 expression levels in colorectal cancer tissues. The expression of ABCE1 was more strongly correlated with tumour samples than with normal colon tissues, as shown in Fig. 5C and D. This finding raises the possibility that methylation regulates ABCE1 expression in colorectal cancer. Moreover, analysis of ABCE1 methylation at CpG islands revealed higher methylation levels in colon tumours than in normal colon mucosa, as shown in Fig. 5E and F. Furthermore, the heatmap shown in Fig. 5G highlights the elevated expression levels of ABCE1 in CpG islands in colorectal cancer samples across various characteristics. To confirm the results of the bioinformatic analysis, 5-Aza, a DNA methylation inhibitor, was used to treat ABCE1 KO HCT-116 cells, and the resulting cytotoxicity was measured. These results suggest that the presence of 5-Aza with ABCE1 KO reduces the cell growth of HT-29 and HCT-116 cells as shown in Fig. 5H. Moreover, metabolic assays, such as glucose uptake and lactate production assays, revealed that the deletion of ABCE1 and treatment with 5-Aza significantly inhibited aerobic glycolysis in HCT-116 cells, as shown in Fig. 5I and J. Moreover, gene expression of ABCE1 reduced by treating 5-Aza with ABCE1 KO in HCT-116 as shown in Fig. 5K. The findings of the present study suggest that ABCE1 could be important for the dynamics of DNA methylation during colorectal carcinogenesis, which could influence the course and outcome of the CRC progression.

ABCE1 plays a major role in DNA methylation visualized from TCGA-COAD datasets. (A) The promoter methylation level of ABCE1 from TCGA-COAD datasets was retrieved from UALCAN database compared between tumour (n = 313) and normal samples (n = 37). (B) The overall survival plot by Kaplan-Meier method denotes the higher expression level of ABCE1 has poor survival rate (HR-1.96) in COAD datasets. (C and D) The correlation of ABCE1 with DNA methylation has been examined by retrieving TCGA-COAD samples from wanderer database. Blue dots denoted normal spearman coefficient value and red dots indicates the tumour samples with spearman coefficient values. (E and F) The methylation levels for ABCE1 have measured between normal and tumour samples in COAD datasets. (G) The clinical characteristics of ABCE1 in DNA methylation for COAD datasets illustrated by heatmap in accordance to their ethnicity, race, BMI, age and event. (H) Cytotoxicity of ABCE1 KO with or without DNA methylation inhibitor, 5-Aza (10µM) for 24 h was measured by MTT assay in HCT-116 cells. (I and J) Deletion of ABCE1 treating in presence and absence of 5-Aza (10µM) was measured glucose uptake and lactate production in HCT-116 cells. (I) ABCE1 expression levels were measured by RT-PCR by treating ABCE1 KO HCT-116 cells with 5-Aza (10µM) for 24 h. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001.

ABCE1 immune infiltration and mutation in COAD datasets

Using the TIMER 2.0 database, we were able to decipher the complex connections between immune cells in the tumour microenvironment while studying the immune cell response to ABCE1 in colorectal cancer. The findings, depicted in Fig. 6A, elucidate a favourable immune response to ABCE1, as indicated by positive correlations with Pearson’s coefficient across various immune cell types: B cells (r = 0.157), CD8 + T cells (r = 0.336), CD4 + T cells (r = 0.082), macrophages (r = 0.208), neutrophils (r = 0.218), and dendritic cells (r = 0.17). This well-thought-out investigation clarifies ABCE1’s possible function in influencing several immune cell types in relation to colorectal cancer.

Immune infiltration, mutation frequency, and IHC of ABCE1 in COAD datasets. (A) ABCE1 in COAD datasets correlated with the immune cells (B cells, CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) were retrieved from TIMER 2.0 database. The partial coefficient curve (r, Pearson’s co-efficient) and p values were denoted. (B) The cumulative survival of immune cells (B cells, CD8 + T cells, CD4 + T cells, macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells) were represented according to Kaplan-Meier plot. High expression (Top 35%) and low expression (bottom 35%) were represented in red and blue color. (C and D) The alteration frequency for ABCE1 in colon adenocarcinoma was visualized by cBioportal database. Among structural variant, mutation and CNA were monitored for ABCE1 expression from various datasets. Moreover, genetic alterations (Missense, Splice, and Truncating mutations) were visualized according to GISTIC profiles, Sample origins, and Study of origin. (E and F) The expression level of ABCE1 in colorectal cancer tissues were visualized by retrieving the immunohistochemical tissues (normal and tumour colon samples) from the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database. (G) Molecular dynamic simulations by GROMACS package were processed by consecutively 50 nanoseconds to check the stability of ABCE1 protein. RMSD, RMS fluctuation, Radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bonds were visualized.

Furthermore, we conducted Kaplan‒Meier analysis24 to explore overall survival rates in relation to immune cell infiltration and ABCE1 expression in patients with colorectal cancer. As depicted in Fig. 6B, indicating that high ABCE1 expression (top 35%) was correlated with poorer overall survival rates for immune cells. This finding highlights the important role of ABCE1 in the interaction between immune cells and the development of colorectal cancer. Moreover, we investigated the mutational alterations in ABCE1, revealing genetic variations such as missense, splice, and truncating mutations, as illustrated in Fig. 6C and D. These findings contribute to our understanding of the genetic landscape associated with ABCE1 in colorectal cancer. Additionally, we explored the disparity in ABCE1 protein expression between normal and colon cancer tissues using immunohistochemical staining data obtained from the HPA database. A substantial increase in ABCE1 expression within colon tissue shown in Fig. 6E and F, further emphasizing the potential relevance of ABCE1 in the context of colon cancer. Molecular dynamics analysis using GROMACS package for the ABCE1 protein exhibited stability over 50 nanoseconds, with strong metrics in RMSD, RMS fluctuations, radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bonds, as demonstrated in Fig. 6G.

Protein‒protein interactions of ABCE1 and associated targets

To identify potent targets and enriched pathways associated with ABCE1 in colorectal cancer, we leveraged multiple resources, including GSE33113 (Supplementary Table 1), the CTD database25(Supplementary Table 2), and GeneCards26 (Supplementary Table 3), to identify significant targets and pathways associated with ABCE1 in colorectal cancer. From these sources, we discovered 64 targets (Supplementary Table 4) that overlapped across the datasets, indicating their relevance to ABCE1 in venn diagram, as shown in Fig. 7A. We next used the STRING database to create a protein‒protein interaction (PPI) network, and we used a variety of Cytoscape plugins (such as Clustvis, MCODE and Cytohubba) to conduct a thorough study (Fig. 7B-D). This analysis revealed the top 15 hub genes intricately linked to ABCE1 in colorectal cancer, as shown in Fig. 7E and F. Exploring the functional aspects, our gene ontology predictions highlighted the involvement of ABCE1 in crucial biological processes, such as the glycolytic process, glucose homeostasis, the apoptotic process, and regulation of the cell cycle and growth. The molecular functions associated with ABCE1 include kinase binding, channel activity, glucose membrane transporter, and protein kinase binding, whereas the cellular components associated with ABCE1 include organelle outer membranes, mitochondrial membranes, nucleus, and nuclear membranes, as depicted in Fig. 7G. Furthermore, as illustrated in Fig. 7H, butterfly plot highlighted the critical functions of ABCE1 involved in a number of signalling pathways, including the p53, PI3K/Akt, and glycolytic pathways. This comprehensive network analysis and functional annotations collectively suggest that targeting ABCE1 through signalling pathways could offer therapeutic potential against colorectal tumorigenesis.

ABCE1 interacts highly associated targets and functional annotations in COAD datasets. (A) CTD database (n = 253), GSE33113 (n = 3415), and gene cards (n = 1734) retrieval of target genes were illustrated as Venn diagram denotes commonly overlapping targets (n = 64) which are strongly associated with ABCE1. (B) Using STRING, web-server for protein-protein interaction was visualized. (C) The interaction file was illustrated in cytoscape software. The diagram shows the association of potent targets by interaction of ABCE1. (D) Using MCODE plugin the PPI has scrutinized. (E and F) Using ClustVis, plugin scrutinized top 15 hub genes in accordance to their Rank (1), nodes (15), edges (120), modularity (2.308), InDeg (120), and their OutDeg (52), indicated in green color. (G) The functional annotation (GO) was visualized in bubble chart (BP, CC, MF) according to their p value and gene count. (H) Butterfly plot represents the highly enriched pathways from KEGG (Pink color) and Reactome (Brown color) with the top 15 genes by their enrichment score (-log10(p value)). CTD, Comparative Toxicogenomic Database; GO – Gene Ontology; BP, Biological Processes; CC, Cellular Component; MF, Molecular Functions.

Irinotecan inhibits cell growth and metabolically regulates colorectal cancer cells

Most genes in the integrated cancer pathway were shown to be favourably regulated according to gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), especially those in the colorectal cancer pathways, as shown in Fig. 8A. Analysis of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopaedia (CCLE) heatmap revealed the upregulation of ABCE1 expression in numerous colon cancer cell lines, with notably high expressions were observed in the HCT-116 and HT-29 cell lines, as shown in Fig. 8B. The 2D structure of irinotecan is shown in Fig. 8C. Treatment of NCM-460, HCT-116, and HT-29 cells with irinotecan for 24 and 48 h resulted in the inhibition of cell growth. Notably, compared with normal colon mucosa, NCM-460, and HCT116 and HT-29 tumour cells exhibited significant inhibition of cell growth at 48 h (Fig. 8D). The IC50 values of irinotecan for 48 h (HCT-116: 53.98 µM; HT-29: 39.17 µM) were determined for additional experiments. Further investigations into the role of irinotecan in regulating glycolysis involved treating colorectal cancer cells with the glycolytic inhibitor 2DG along with irinotecan. The results indicated that 2DG at various concentrations (4 mM and 8 mM) in combination with irinotecan reduced the growth of HCT-116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells, as shown in Fig. 8E. The GSEA data shown in Fig. 8F suggest a correlation between ABCE1 and the upregulation of glycolysis and metabolic reprogramming in colon cancer tissue samples. To validate these bioinformatic findings, glucose uptake and lactate production were measured in colorectal cancer cells treated with irinotecan. The results demonstrated that irinotecan treatment reduced glucose consumption and lactate production in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells (Fig. 8G and H). Moreover, the antioxidant role of irinotecan was examined by measuring cellular catalase and SOD activity in colorectal cells, which revealed inhibition of cellular CAT and SOD activity levels, whereas treatment with irinotecan decreased SOD and CAT activity in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells (Fig. 8I and J). Overall, our findings provide strong evidence that the irinotecan inhibits cell growth and controls metabolism in colorectal cancer cells.

ABCE1 plays an oncogenic role in colorectal cancer cells. (A) GSEA plots from Wiki pathway shows the involvement of ABCE1 in Integrated cancer pathway. (B) The heatmap illustration mentioned the ABCE1 expression levels (TPM) among various colon cancer cell lines. (C) Chemical structure of irinotecan. (D) MTT assay for cell viability shows the increasing concentration of irinotecan (10–100µM) for 24–48 h intervals in NCM-460, HCT-116, and HT-29 cells. IC50 values were calculated using Graphpad prism software. IC50 concentration value of irinotecan for 48 h (HCT-116: 53.98µM; HT-29: 39.17µM) was followed for further experiments. (E) Cell viability by MTT assay was examined by pre-treating with glycolytic inhibitor, 2DG (4 mM and 8 mM) along with irinotecan in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. (F) GSEA plots represents the role of glycolysis and metabolic reprogramming in colon cancer from GSE33113 dataset. (G and H) The glucose uptaken and lactose production was examined by treating irinotecan in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. (I and J) The cellular catalase (CAT) and Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) was measured comparing untreated and irinotecan treated in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001.

Irinotecan promotes cell cycle arrest and induces apoptosis in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells

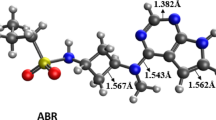

To further corroborate the effectiveness of irinotecan against colorectal cancer, flow cytometry analysis was conducted. Compared with untreated and treatment with irinotecan for 48 h resulted in inhibition of the synthesis phase in HCT-116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells, as shown in Fig. 9A. These results suggest that irinotecan causes HCT-116 and HT-29 colorectal cancer cells to undergo G1 phase cell cycle arrest. Furthermore, annexin V-FITC/PI double staining method was used to measure cell death. Figure 9B shows that, compared with the control cells, the HCT-116 and HT-29 cells induced early and late apoptosis. These biological results were corroborated by GSEA plots (Fig. 9C), which revealed that tumour samples from CRC datasets exhibited positive regulation of the cell cycle and negative regulation of apoptosis and the TCA cycle relative to normal tissues. Decreased ABCE1 expression in colorectal cancer cells is also shown in Fig. 9D, providing additional support for the bioinformatic analysis. RT‒PCR was used to measure ABCE1 expression levels in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells treated with irinotecan. Immunoblot analysis confirmed these results, revealing reduced levels of ABCE1 after 48 h of irinotecan treatment in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells, as shown in Fig. 9E. These findings clearly demonstrated that the treatment of irinotecan regulates the cell cycle and induces cell death in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. Furthermore, a significant binding relationship between ABCE1 and irinotecan was found by molecular docking analysis, with hydrogen bond interactions shown (TYR A: 281) in Fig. 9F. To further analyse the interaction between ABCE1 and irinotecan, molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the GROMACS software package. These interactions significantly affected the results of the energy calculations (Supplementary Table 5), with RMSD, solvent-accessible surfaces, radius of gyration, and RMS fluctuations reported for ABCE1 with irinotecan, as shown in Fig. 9G.

Irinotecan promotes cell cycle and induces cell death in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. (A) The cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry was measured by treating irinotecan in colorectal cancer cells. (B) Cell death by Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining was measured by flow cytometry in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. (C) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plots represent interaction of ABCE1 with cell cycle pathway, Apoptosis, and negative regulation of TCA cycle from GSE33113 colon adenocarcinoma datasets. (D) The treatment of irinotecan was subjected to evaluate the gene expression levels of ABCE1 in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells by RT-PCR. (E) Immunoblot analysis shows the expression level of ABCE1 with and without treatment of irinotecan in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. β-actin was used as an internal control. Uncropped western blot images corresponding to Fig. 9E can be found in Supplementary Fig. 4b. (F) To find out the binding association with ABCE1 and irinotecan, molecular docking was implemented. 3D and 2D structure illustrations shows the binding amino residues between the ligand and protein complex. Hydrogen bond binding between ABCE1 and irinotecan was visualized using Biovia Discover studio. (G) Molecular dynamics was executed using GROMACS software package to understand the atomic level interactions between ABCE1 and irinotecan. Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Solvent accessible surface, Radius of gyration (Rg), and RMS fluctuation plots and energy calculations were generated from GROMACS software.

Deletion of ABCE1 reduced cell growth and abrogates metabolic reprogramming in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells

ABCE1 was deleted with the CRISPR/Cas9 system, which reduced the growth of HT-29 and HCT-116 cells in a time-dependent manner, as shown in Fig. 10A. ABCE1 KO HT-29 and HCT-116 cells demonstrated inhibited glucose uptake and lactose production, which led to the inhibition of aerobic glycolysis in CRC cells, as shown in Fig. 10B. Moreover, ABCE1 KO confirmed by western blot as shown in Fig. 10C and cell death was also measured by flow cytometry, which revealed that the deletion of ABCE1 induced apoptosis in HT-29 and HCT-116 cells (Fig. 10D). Furthermore, to examine the combined therapy of ABCE1 deletion with irinotecan was investigated and resulted significant inhibition of cell growth by treating ABCE1 KO and Irinotecan in HCT − 116 and HT-29 cells as shown in Fig. 10E. The glucose uptaken and production of lactic acid were reduced in combined treatment compared to alone in CRC cells as shown in Fig. 10F and G. To check the anti-oxidant property, total cellular SOD levels were observed and result demonstrated that ABCE1 KO with irinotecan reduced the SOD levels in HCT − 116 and HT-29 cells in Fig. 10H. The gene expression by RT-PCR was experimented shows reduced ABCE1 expression by treating ABCE1 KO with irinotecan in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). These results suggested that knockout of ABCE1 with irinotecan significantly reduced cell growth and induced apoptosis in CRC cells.

ABCE1 promotes cell growth and abrogates cell death in CRC cells. (A) Cell viability of WT or ABCE1 KO HT-29 and HCT-116 cells were measured by MTT at 24 h to 72 h. (B) Glucose uptake and lactate production assays were measured at 24 h in WT and ABCE1 KO HT-29 and HCT-116 cells. (C) Western blot analysis shows the depletion of ABCE1 in HT-29 and HCT-116 cells. (D) WT and ABCE1 KO HT-29 and HCT-116 cells were examined for apoptotic rate by flow cytometry. (LL: Live cells, UL: Early apoptosis, UR: Late apoptosis, LR: Necrosis). (E) ABCE1 KO and Irinotecan combined treatment shows cytotoxicity in HCT-116 and HT-29 cells. (F and G) Glucose uptake and lactose production assays were measured by treating ABCE1 KO and irinotecan. (H) Total SOD activity was measured. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001. Uncropped western blot images corresponding to Fig. 10 C can be found in Supplementary Fig. 4c.

ABCE1 modulates aerobic glycolysis and cell growth via the p53 signalling pathway in HCT-116 cells

The results of the bioinformatic analysis depicted in Fig. 11A revealed that colorectal cancer datasets are highly associated with the p53 signalling pathway. Bubble plot data derived from colorectal cancer tissues which revealed a substantial correlation between ABCE1 and the p53 signalling pathway. These findings suggest a significant association between ABCE1 and the p53 signalling pathway in colorectal cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A). To validate these findings, cell viability was assessed by treating HCT-116 cells with the p53 pathway activator nutlin-3a (nut-3a). The results of the MTT assays (IC50−68.74µM) demonstrated that nut-3a inhibits the growth of colorectal cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Irinotecan and nut-3a were used to treat HCT-116 cells to study the modulation of p53 signalling pathway. The results revealed significant inhibition of cell growth when both irinotecan and nut-3a were administered to HCT-116 cells (Fig. 11B). Furthermore, metabolic assays of glucose uptake and lactose production revealed reduced levels in HCT-116 cells, as shown in Fig. 11C and D. In addition, antioxidant analysis was performed, and the results revealed that catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities were reduced in response to irinotecan and nut-3a treatment in HCT-116 cells (Fig. 11E and F). Treatment of HCT-116 cells with irinotecan and nut-3a significantly increased G1 phase cell cycle arrest, as shown in Fig. 11G. These results suggest that an irinotecan enhances G1 phase cell cycle arrest by modulating the p53 signalling pathway in colorectal cancer cells. Furthermore, apoptosis was also confirmed that, compared with the individual treatments, the combination treatment clearly induced early and late apoptosis in HCT-116, as shown in Fig. 11H. Gene expression analysis was performed by RT‒PCR, and the results revealed that HCT-116 cells treated with the combination of irinotecan and nut-3a clearly presented increased expression levels of p53, CDKN1A, and BAX but reduced expression levels of BCL2, LDHA and GLUT2, as shown in Fig. 11I. Moreover, deletion of ABCE1 treated with nut-3a resulted reduced cell growth, altered glucose uptake, lactate production, and promotes G1 phase cell cycle arrest in HCT-116 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3). These experimental validations concluded that the ABCE1 KO or irinotecan in presence of nut-3a alters the p53 signalling in HCT-116 cells. The results of the molecular docking analysis also demonstrated that irinotecan exhibited high binding affinity with p53 signalling targets such as TP53, GLUT2, BAX, LDHA, BCL2, MDM2, CDKN1A, and PDK1 (Supplementary Table 6) (Fig. 12). These findings imply that p53 signalling pathway activation through ABCE1 regulates cell proliferation and the warburg effect in colorectal cancer cells.

Irinotecan inhibits cell growth and aerobic glycolysis via p53 signalling in HCT-116 cells. (A) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plot illustrate the involvement of p53 signalling pathway from COAD dataset (GSE33113). (B) HCT-116 cells were subjected to treat with irinotecan with and without nut-3a cell viability was measured. (C and D) Glucose uptake and lactose production were measured by treating irinotecan and combing with nut-3a in HCT-116 cells. (E and F) ROS activity was also measured by evaluating the cellular SOD and CAT by treating irinotecan and nut-3a alone and in combined in HCT-116 cells. (G) cell cycle analysis by flow cytometry was measured by treating irinotecan with and without nut-3a in HCT-116 cells. (H) Cell death by Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining was measured by treatment of irinotecan and nut-3a in HCT-116 cells. (I) Gene expression of p53, p21, BAX, BCl2, LDHA, and GLUT2 was examined by RT-PCR by treating irinotecan and nut-3a alone and in combined in HCT-116 cells. Statistical significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001.

Discussion

Cancer, an intricate and diverse problem, is typified by unchecked cell growth that frequently results in the formation of malignant tumours27,28. Its impact can be felt across various organs and tissues, disrupting normal bodily functions and presenting formidable obstacles in terms of diagnosis, treatment, and overall management. Typically, colon cancer begins as benign polyps on the inner linings of these organs, gradually progressing into cancerous growth over time. Risk factors for this disease include age, genetic predispositions, lifestyle choices including food and exercise, and family history29,30. Early detection facilitated through screening measures such as colonoscopies significantly enhances patient prognosis and treatment efficacy. However, despite strides in diagnosis and treatment, colorectal cancer remains a pressing public health concern, underscoring the imperative for ongoing research and innovation in cancer prevention, detection, and therapeutic strategies. In current treatment strategies for colorectal cancer, a combination of approaches is often employed to effectively combat the disease31. Chemotherapy, administered either before or after surgery, uses drugs to kill cancer cells or inhibit their growth, often in combination regimens such as FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin)32. Moreover, irinotecan, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, is a key chemotherapeutic agent for treating metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC). It induces DNA damage by preventing the re-ligation of single-stranded DNA breaks, causing double-strand breaks and triggering apoptosis in cancer cells. Combining irinotecan with molecular targeted therapies, which inhibit critical pathways involved in cancer survival, proliferation, and metastasis, has shown promise in enhancing treatment efficacy, reducing drug resistance, and minimizing toxicity, making it a vital strategy in advanced CRC management33,34,35. In this study, we utilised irinotecan combined with deletion of ABCE1 in CRC cells.

Before surgery, radiation therapy can be used to reduce the tumour size. In more advanced situations, it can be used as a palliative measure to improve symptoms. Targeted therapy has emerged as a significant advancement in CRC treatment, with a focus on specific molecular targets involved in cancer growth and progression33. In CRC, biomarkers are essential for guiding therapy choices and enhancing patient outcomes. These biomarkers, which can be proteins, genes, or other molecules, provide valuable information about the molecular characteristics of a tumour, its prognosis, and its response to specific treatments34,35. Personalized treatment plans are made possible using biomarker-driven techniques, guaranteeing that patients receive the best medications suited to their unique tumour biology36. ABCE1 has emerged as a pivotal player in cancer cells and influences multiple facets of malignant behaviour. Within the intricate landscape of cancer progression, ABCE1 orchestrates diverse cellular processes that collectively contribute to tumorigenesis and metastatic dissemination.

Additionally, ABCE1 is a potential target for cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Two peptides derived from ABCE1 demonstrate the capacity to efficiently stimulate HLA-A2-restricted CTLs with cancer reactivity from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with colon cancer37. Moreover, its involvement in translation regulation underscores its importance in sculpting the proteomic landscape of cancer cells, potentially tipping the balance towards oncogenic phenotypes. Furthermore, increased ABCE1 expression, which is clinically linked to aggressive tumour growth and invasion, likely increases the G-actin reservoir, which promotes the ability of lung cancer cells to invade and produce protrusions38. Indeed, the prospect of targeting ABCE1 in cancer therapy looms large, with the promise of restraining tumour growth and sensitizing cancer cells to conventional treatment modalities. One of our previous studies identified ABCE1 as a potent molecular prognostic biomarker against colorectal cancer (CRC)39.

Numerous biological activities, including translation, antiapoptotic activity, and cell proliferation, have been linked to the ABCE1 gene. Preliminary bioinformatic analyses across multiple cancer datasets revealed significant upregulation of ABCE1 expression in various cancers, including colorectal cancer (Fig. 1). In particular, ABCE1 expression was greater in tumour samples than in normal samples in colorectal cancer datasets, and these differences were significantly correlated with clinical parameters such as race, age at diagnosis, and vital status. Moreover, analysis of genetic data types revealed a high mutation frequency in ABCE1. Further analysis using GSEA software revealed significant regulation of cancer-related pathways in colorectal cancer datasets, indicating the association of ABCE1 upregulation with colorectal cancer progression.

One of the previous studies aimed to identify genetic markers that can be used to predict treatment outcomes and survival rates in patients with CRC41. We used Kaplan‒Meier (KM) plots from the COAD datasets to perform a thorough investigation of the predictive value of ABCE1 to confirm the possible carcinogenic role of this gene in colorectal cancer. KM analysis revealed compelling evidence indicating that patients with elevated ABCE1 expression in advanced stages (Stages III and IV) of colorectal cancer experienced notably poorer OS rates than those with elevated ABCE1 expression in early stages (Stages I and II). Similarly, the DFS analysis corroborated these findings, demonstrating that patients with low ABCE1 expression in advanced stages exhibited higher survival rates than did those with low ABCE1 expression in early stages, as shown in Fig. 4B. These findings highlight the potential of ABCE1 as an oncogene and a viable target for the treatment of colorectal cancer. A previous study investigated the role of upstream open reading frames (uORFs) within the 5’ leader sequence of the human ABCE1 gene, employing experimental techniques such as semiquantitative RT‒PCR and statistical analysis to explore translation regulation. These findings suggested that specific uORFs in the 5’-leader sequence could effectively suppress translation of the main coding sequence40.

Our analysis of ABCE1 expression levels in primary tumours versus normal colon tissues revealed its upregulation in tumours, suggesting its potential role in colorectal cancer progression. Additionally, we examined the relationship between promoter methylation levels and ABCE1 expression. ABCE1 plays in epigenetic process that governs chromatin shape and gene expression is DNA methylation. Mutant DNA methylation patterns, such as worldwide hypomethylation and hypermethylation of oncogenes and tumour suppressor gene promoters, are frequently observed in cancers, particularly colorectal cancer41. Additionally, analysis of ABCE1 methylation at CpG islands revealed higher methylation levels in colon tumours than in normal colon mucosa, as demonstrated in Fig. 5E and F. The heatmap in Fig. 5G further highlights the elevated expression levels of ABCE1 in CpG islands across various characteristics in colorectal cancer samples. These results suggest that ABCE1 affects DNA methylation dynamics during colorectal carcinogenesis, which may have an impact on the course and prognosis of the illness.

Our investigation of the immune response to ABCE1 in colon cancer using the TIMER database revealed intriguing interactions within the tumour microenvironment. These results provide insight into the capacity of ABCE1 to influence various immune cell types in relation to colon cancer. To further elucidate the impact of ABCE1 on patient outcomes, we conducted Kaplan‒Meier analysis to explore overall survival rates in relation to immune cell infiltration and ABCE1 expression in patients with colon cancer. Figure 6B reveals a notable trend, indicating that high ABCE1 expression is correlated with poorer overall survival rates for immune cells, underscoring the significant impact of ABCE1 on the interplay between immune cells and colon cancer progression. Moreover, we delved into mutation alterations in ABCE1, revealing genetic variations such as missense, splice, and truncating mutations (Fig. 6C and D), contributing to our understanding of the genetic landscape associated with ABCE1 in colon cancer. By examining the disparity in ABCE1 protein expression between normal and colon cancer tissues using IHC staining data obtained from the HPA database (Fig. 6E and F), we observed a substantial increase in ABCE1 expression within colon tissues, further emphasizing its potential relevance in the context of colon cancer. Furthermore, molecular dynamics simulations performed using the GROMACS package for the ABCE1 protein exhibited stability over 50 nanoseconds, with strong metrics in RMSD, RMS fluctuations, radius of gyration (Rg), and hydrogen bonds (Fig. 6G), providing valuable insights into the structural stability and dynamics of ABCE1. To identify potent targets and enriched pathways associated with ABCE1 in colorectal cancer, we integrated data from multiple resources, including GSE33113, the CTD database, and GeneCards. This comprehensive analysis revealed 64 targets overlapping across datasets, highlighting their relevance to ABCE1 in colorectal cancer.

ABCE1 plays crucial roles in the proliferation, invasion, and apoptosis of MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Furthermore, it has been proposed that ABCE1 inhibits intracellular RNase L activity, which disrupts the 2–5 A/RNase L pathway and affects a number of biological properties of breast cancer cells42,43. This study investigated the efficacy of irinotecan in colorectal cancer cells using a comprehensive approach involving GSEA, cancer cell line profiling, metabolic regulation, antioxidant activity, flow cytometry, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations. Initially, GSEA revealed positive regulation of genes within the integrated cancer pathway, particularly in colorectal cancer targets. Analysis of a heatmap generated from Cancer Cell Line Encyclopaedia (CCLE) data demonstrated the upregulation of ABCE1 expression in various colon cancer cell lines, notably HCT-116 and HT-29 cells.

The 2D structure of irinotecan was visualized, and compared with normal colon mucosa, treatment with irinotecan significantly inhibited the growth of colorectal cancer cells. Further investigation into the role of irinotecan in regulating glycolysis revealed its inhibitory effect on cell growth when combined with the glycolytic inhibitor 2DG. GSEA data revealed a correlation between ABCE1 expression and the upregulation of glycolysis and metabolic reprogramming in colon cancer tissue samples. Glucose uptake and lactate production assays confirmed that the levels were reduced upon irinotecan treatment in colorectal cancer cells. Additionally, irinotecan inhibited cellular catalase and SOD activity, indicating its antioxidant role. ABCE1 is involved in translation, DNA synthesis, and cell cycle progression through its regulation of histone protein synthesis44. Following irinotecan therapy, flow cytometry analysis revealed G1 phase cell cycle arrest and the induction of apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. GSEA plots demonstrating positive control of the cell cycle and negative control of apoptosis in tumour samples provided evidence for this effect. RT‒PCR and immunoblot analysis confirmed that ABCE1 expression was reduced after irinotecan treatment (Fig. 9D and E). Molecular docking analysis revealed that ABCE1 has a strong binding relationship with irinotecan, and hydrogen bond interactions were observed (Fig. 9). Molecular dynamics simulations further supported these interactions, indicating stability and favourable energy calculations. ABCE1 deletion decreased the growth of HT-29 and HCT-116 cells in a time-dependent manner. The knockout of ABCE1 in these cells led to reduced glucose uptake and lactate production, thereby inhibiting aerobic glycolysis in colorectal cancer (CRC) cells. Additionally, flow cytometry analysis demonstrated that ABCE1 deletion induced apoptosis in HT-29 and HCT-116 cells.

The bioinformatic analysis depicted in Fig. 10A revealed a significant association between colorectal cancer datasets and the p53 signalling pathway. Further investigations into the role of ABCE1 in mediating the p53 signalling pathway involved treating colorectal cancer cells with a combination of irinotecan and nut-3a. When irinotecan and nut-3a were given to HCT-116 cells, the findings demonstrated considerable suppression of cell proliferation.

Furthermore, the antioxidant properties were assessed, revealing reduced levels of cellular catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity upon treatment with both irinotecan and nut-3a in HCT-116 cells. These results suggest that the activation of the p53 signalling pathway by ABCE1 modulates cell growth and the warburg effect in colorectal cancer cells. Cell death was confirmed by flow cytometry, which revealed that, compared with the individual treatments, the combination treatment induced early and late apoptosis more effectively in HCT-116 cells (Fig. 11). Additionally, gene expression analysis by RT‒PCR confirmed the increased expression levels of p53, CDKN1A, and BAX and the reduced expression levels of BCL2, LDHA, and GLUT2 in colorectal cancer cells treated with the combination of irinotecan and nut-3a. Molecular docking analysis revealed the high binding affinity of irinotecan for p53 signalling targets such as TP53, GLUT2, BAX, LDHA, BCL2, MDM2, CDKN1A, and PDK1, further supporting the role of ABCE1 in modulating the p53 signalling pathway. 3D and 2D structure visualizations confirmed these interactions (Fig. 12). Similarly, another study reported that increased expression levels of ABC transporters (ABCA12, ABCC2, and ABCE1) were observed in oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells, with CK2α knockdown effectively reversing these effects. Lowering CK2α expression led to the inhibition of oxaliplatin resistance, the induction of apoptosis, and the suppression of sphere formation45. Overall, these results confirm that inhibition of ABCE1 through the p53 signalling pathway promotes G1 phase cell cycle arrest and induces death in CRC cells. From these analyses, we confirmed that targeting ABCE1 could be a better therapeutic option as a molecular targeted therapy against colorectal tumorigenesis.

Conclusion

The findings of the present study highlight ABCE1 as a promising biomarker in CRC and elucidate its intricate molecular mechanisms. Integrated bioinformatic analyses and experimental validation revealed that ABCE1 KO and irinotecan reduced cell growth, induced G1 phase cell cycle arrest, and promoted apoptosis in CRC cells. This study also highlights the involvement of ABCE1 in aerobic glycolysis and oxidative processes, as demonstrated through the modulation of the p53 pathway in HCT-116 cells. To conclude, ABCE1 is a possible therapeutic target for the management of CRC, highlighting its importance in developing treatment approaches for CRC progression.

Materials and methods

GEO datasets from colorectal clinical samples

The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), overseen by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) and accessible at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, serves as a comprehensive repository for genetic expression data46. Stringent inclusion criteria guided our selection process for datasets. Following these criteria, we identified and obtained the gene expression profile(s) designated as GSE33113 (6 colorectal cancer samples and 90 healthy controls), which comprises colorectal carcinoma (CRC) samples47. This dataset was meticulously curated and organized utilizing the GPL570 Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array platform.

Normalizing GSE datasets

Transforming each dataset’s probes into standard gene symbols was the initial stage in evaluating the colorectal cancer datasets found in the Series Matrix File for GSE33113. In order to make the interpretation of microarray findings easier, this conversion is necessary to make sure that gene identities are consistent with a standard nomenclature. We used the multi-array average approach to normalize the colorectal cancer clinical samples from these datasets in order to improve comparability and minimize any technical biases. Through the use of R software (version 2.6.0), the gene expression data within each dataset were normalized to a similar distribution and scale. By reducing systematic differences between samples or experimental settings, normalizing the data made it easier to compare and analyze different datasets.

Identification of potent DEGs in CRC datasets

DEGs in CRC dataset were created using GEO2R48. The Volcano Plot, accessed via the GEO2R tool at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/, The depiction shows statistical significance (p-value) on the y-axis and fold change in gene expression on the x-axis. This graphical presentation assists in identifying genes exhibiting significant alterations in expression levels. Furthermore, a comprehensive analysis of the dataset was conducted utilizing GEO2R (GSE33113), the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD), and Genecards. Targets associated with CRC, as well as ABCE1, were extracted and visually presented using FunRich V3.1.3 software.

mRNA expression status for COAD datasets

The mRNA expression levels of ABCE1 in colorectal cancer were analysed across multiple datasets, including those from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://www.cancer.gov/ccg/research/genome-sequencing/tcga)49. mRNA expression data for ABCE1 were obtained from TCGA datasets, comprising 41 normal samples and 286 tumour samples. Analysis was performed across various stages of colorectal cancer (I-IV), different age groups (21–100 years), and nodal metastasis statuses (N0-N2) using the UALCAN database. Furthermore, overall survival plots for ABCE1, including high and low expression curves with Hazardous Ratio (HR), were generated using data from the GEPIA database. Furthermore, from datasets made available by The Clinical Proteomic Tumour Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), the protein expression levels of ABCE1 were retrieved for 100 normal samples and 97 tumour samples.

Survival analysis from COAD datasets

To investigate survival rates, encompassing Overall Survival (OS) and Disease-Free Survival (DFS), and assess the correlation between potential targets in colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, the study leveraged multiple databases, including UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/) and GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/)50,51. The Kaplan-Meier (KM) technique was used to calculate survival rates, and log-rank tests were added to assess statistical significance. The study employed a significance criterion of p < 0.05 to detect noteworthy correlations between the gene expression levels and the survival of patients.

DNA methylation status from COAD datasets

The DNA methylation status of colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD) datasets was investigated using the Wanderer database (http://maplab.imppc.org/wanderer/)52. This analysis aimed to explore the epigenetic modifications associated with COAD development and progression. The Wanderer database’s COAD datasets were used in this investigation to compare the DNA methylation patterns of CpG sites in COAD tumour samples (n = 313) to their counterparts in normal tissue (n = 37).

Immune infiltration and correlation of immune cells from COAD datasets

Using the TIMER database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/), we conducted an extensive analysis of immune infiltration associated with ABCE1 in colorectal cancer (CRC)53. These quantifications were based on the gene expression profile of ABCE1 within colon cancer samples. Furthermore, we examined the overall survival patterns of ABCE1 in colorecatal cancer by categorizing high and low expression rates for each of the six immune cell types. This examination was conducted by analyzing cumulative survival rates (%) and time in months, providing a comprehensive overview of the impact of ABCE1 expression.

Mutation and immunohistochemical analysis for COAD samples

Target gene mutation and expression profiles from colorectal tissue samples were collected using the cBio Cancer Genomics Portal (http://cbioportal.org) in TCGA datasets54. Through three colorectal cancer (CRC) investigations, a comprehensive mutation analysis encompassing the identification of mutations, amplifications, and deletions is made possible by this site. Additionally, utilizing the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database, which is accessible at (https://www.proteinatlas.org/), the study examined the protein levels of ABCE1 in tumour and normal tissues55.

Protein-Protein interactions

The Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network was assessed by utilizing targets sourced from the Comparative Toxicogenomic Database (CTD) (https://ctdbase.org/) and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/). Venn diagrams generated from the FunRich tool aided in identifying overlapping genes, while the STITCH database (https://stitch.embl.de/), dedicated to analyzing protein-protein interactions, contributed to further insights. The identified Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) were then employed to construct and visually represent the PPI network using Cytoscape software (version 3.5.1; http://www.cytoscape.org). The edges that connected the proteins in this created PPI network were scaled based on the total score, which indicated how strongly the proteins interacted with one another. Visualization of this network was facilitated through the utilization of ClustVis, cytohubba, and MCODE plugins.

Functional annotations and pathway prediction

In order to clarify the biological significance of the discovered Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) and gene clusters, a thorough functional and pathway enrichment analysis is essential. We thoroughly investigated the biological roles and possibly enhanced pathways connected to the biomolecules that were up-regulated. To achieve this, we utilized the g: Profiler database56, accessible at https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/. Furthermore, to find pathways exhibiting notable enrichment with the discovered DEGs in colorectal cancer, KEGG pathway analyses57 were carried out.

Molecular Docking

The study explores the binding interactions between Irinotecan (CID: 60838) and several proteins, including TP53 (1TUP), GLUT2 (4YBQ), BAX (1F16), LDHA (4O29), BCL2 (4IEH), and MDM2 (1YCR), CDKN1A (1AXC), AND PDK1 (2O28) structures were obtained from the PDB (https://www.pdb.org/pdb). Docking calculations were performed using the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm (LGA) with a maximum of 100 genetic algorithm cycles. PyRx software was used to make the docking analysis easier. The outcomes of the docking study were then seen and examined using Discovery Studio 2021, which included both 3D and 2D structural evaluations.

Molecular dynamic simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) studies were conducted using the GROMACS package. The docked complexes were initially separated into protein (ABCE1) and ligand (Irinotecan). Receptor topology was generated using the GROMOS all-atom force field, and water was added explicitly using the Simple Point Charge (SPC) water model. Subsequently, the ABCE1-irinotecan complex was constructed using both the receptor and ligand topologies. Additional file preparation steps included adding ions, performing energy minimization for 1000 steps, and equilibration (NVT, NPT) for 300 picoseconds at 300 K temperature and 1 bar pressure, following the MDP files. Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) was employed to calculate the electrostatic forces. Neutralization of the complexes was performed by adding 0.15 M NaCl salt to the system. The prepared files were transferred to the cluster using the SFTP command in Ubuntu for MD simulations spanning 100 nanoseconds. Subsequently, various analyses such as RMSD, RMSF, Radius of Gyration, SASA, Hydrogen bond analysis, and MMPBSA were performed using the trajectory file (XTC) of the complexes.

Cell culture and ABCE1 deletion cell lines

The HCT-116 and HT-29, colorectal cancer cells were acquired from NCCS, Pune. Normal colon mucosa, NCM460 cells were purchased from ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA. The CRC cells were maintained and passaged in a CO2 incubator, with culture media consisting of DMEM media from HiMedia supplemented with 10% FBS and a combination of 1% penicillin and streptomycin antibiotics. ABCE1 knockout (KO) cells were generated in HCT-116 and HT-29 cell lines using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Cells were transfected with 1 µg of the ABCE1 plasmid (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no: sc-423949) and transfection reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no: sc-395739), following the manufacturer’s instructions. GFP-positive cells were identified and confirmed in colorectal cancer cells by western blot analysis.

Cell viability by MTT assay

The MTT test was performed in accordance with the recommended methodology to assess the cytotoxic effects of irinotecan and nut-3a on the HCT-116 cell lines58. ABCE1 KO cells with or without methylation inhibitor, 5-AZAcytidine (Cat no. A2385, Sigma-Aldrich) were measured the cytotoxicity at 24–72 h. The experimental procedure commenced by seeding an initial population of 3000 cells in 96-well plate, which were allowed to incubate overnight. The formazan crystals that formed during this incubation period were dissolved with DMSO (100 µl) after the cell culture was exposed to the MTT reagent (5 mg/ml). Cell viability was then assessed by measuring absorbance at 570 ηm using Elisa Reader (Robonik, India).

Metabolic assays

Briefly, 1 × 104 HCT-116 cells per well were seeded in 96-well plate and the cells were allowed to proliferate for 24 h before receiving another 48 h of treating irinotecan (IC50concentration) and nut-3 A. Similarly, after deletion of ABCE1 in CRC cells were further treated with or without 5-AZA for another 24 h. Glucose uptake was measured using a colorimetric kit following the manufacturer’s instructions59. Prior to drug treatment, HCT-116 and HT-29 cells were pre-treated with 4mM and 8mM glycolytic inhibitor, 2-DG for 6 h. Colorimetric kits were used to assess lactate levels in accordance with the guidelines given. LDH enzyme activity was assessed in HCT-116 cells, which were seeded at a density of 4 × 104 cells in 6 well plate and exposed to irinotecan (IC50 concentration) and nut-3a for 48 h. Cell lysates were extracted and incubated with LDH enzymatic mix for an hour before measuring the samples at OD of 450 ηm at microplate reader.

Measurement of cellular catalase activity

With the use of a catalase assay kit purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, the activity of the cellular catalase (CAT) enzyme was measured. To sum up, irinotecan and nut-3a were applied 1 × 104 of HCT-116 cells in 96 well plate during a 48-hour period. Following the treatment, the cells were lysed in lysis buffer and cleaned with PBS before the lysates were collected. After that, these samples were combined in a centrifuge tube with assay buffer. At 25˚C for five minutes, a 200 mM H2O2 solution was added to start the reaction, and a stop solution was added to end it. After 10 min of additional incubation at 25˚C to turn the color reagent red, the mixture was tested for absorbance at 520 nm at microplate reader.

Measurement of cellular SOD activity

The activity of cellular Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) enzyme was evaluated using a SOD Assay Kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA. HCT-116 cells at a population of 1 × 104 were treated with irinotecan (53.98µM) and nut-3a (68.74µM) for 48 h in 96-well plate. Supernatant samples comprising 30 µg of total protein were used to measure SOD enzyme activity after quantification using the Bradford assay. These samples were put into each well of a 96-well microtiter plate that had been filled with an enzyme working solution. The plate was then incubated for 10 min at 25˚C to produce a water-soluble formazan dye. A microplate reader was then used to measure the absorbance at 450 nm.

Cell cycle analysis by PI staining using flow cytometry

To find out how DNA content varied between cell cycle stages, flow cytometric technique was utilized60. HCT-116 cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well in 6 well plate and treated with irinotecan (HCT-116: 53.98µM; HT-29: 39.17µM) and nut-3a at their respective IC50 concentrations for 48 h, following a 24-hour incubation period. The cells were treated with 10 mg/mL of RNase A and then fixed for the night in 70% ice-cold ethanol. The fixed cells were then stained with Propidium Iodide (PI) dye. A BD FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, USA) was used to measure the fluorescence emitted by the PI-labelled nuclei.

Cell death assay by dual staining

To assess cell death in CRC cells, an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit was employed according to the manufacturer’s instructions61. 1 × 106 of HCT-116 were initially incubated in 6 well plate for 24 h and then treated with irinotecan (53.98µM) and nut-3a (68.74µM) for 48 h at the IC50 dose. Briefly, WT and ABCE1 KO CRC cells were seeded in a 6 well plate at a density of 1 × 105 and incubated for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were stained with Propidium Iodide (PI) and Annexin V-FITC for 15 min at 25 °C in the dark. Flow cytometry was utilized to analyze the apoptotic index using a BD FACS Calibur instrument, and the data were interpreted using Cell Quest Pro V 3.2.1 software (Becton Dickinson, USA).

Protein expression by Western blot

Briefly, 5 × 106 NCM-460, HCT-116, and HT-29 cells were sown in a 100 mm culture plate. Following treatment with irinotecan (HCT-116: 53.98µM; HT-29: 39.17µM) for 48 h, the cells were trypsinized, and proteins were extracted using Radioimmune Assay Precipitation (RIPA) buffer (#Cat no. R0278, Sigma). Also, WT and ABCE1 KO CRC cells were incubated for 24 h and then cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot. Total protein content was quantified using Lowry’s method. The proteins were then moved onto a PVDF membrane after being separated by SDS-PAGE. After blocking the membrane for an hour with 2% blocking solution, primary antibodies (anti-ABCE1 antibody, diluted at 1:1000) were added and left to incubate overnight. After washing the membrane with TBS-T and TBS, it was probed with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (diluted at 1:5000) for 1 h. Following another round of washing, enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (ECL) was added. Protein band intensity was quantified using the Quantity One image analysis system (Bio-Rad, USA), with β-actin serving as an invariant control in this study.

Gene expression by RT-PCR

Briefly, 1 × 105of HCT-116 and HT-29 cells were seeded in 6 well plate. The Takara RNA isolation kit was used to extract RNA following an overnight incubation by the methods as described61. The concentration of the extracted RNA was quantified in micrograms (µg) by spectrometric measurement. A reaction mixture was carefully produced using Takara SyBr green master mix and specially made forward and reverse primers that targeted the particular gene ABCE1 for mRNA expression analysis by RT-PCR. The thermal cycling protocol comprised an initial activation step lasting 5 minutes at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of a two-step cycling process. This involved denaturation for 5 seconds at 95 °C, followed by combined annealing and extension for 10 s at the specific primer temperature, which ranged between 55 and 62.5 °C. For Real-Time PCR analysis of other genes (ABCE1, TP53, CDKN1A, BAX, BCL2, LDHA, and GLUT2), a reaction mixture was prepared using Takara SyBr green master mix, along with specifically designed forward and reverse primers targeting these genes as detailed in Supplementary Table 7.

Statistical analysis

For thorough data analysis in this work, the statistical programming language R—which is renowned for its skill in statistical computing was employed. The log-rank test was carefully used with GraphPad Prism 8 to get appropriate p-values in order to assess the significance of mRNA and protein expressions. All experiments involving cells treatment with drugs utilized a minimum of three independent biological replicates. To evaluate overall survival trends, Kaplan-Meier graphs were also carefully constructed. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001, and ***p < 0.0001 were the different significance thresholds used to assess statistical significance across groups.

Data availability

Data availabilityThe datasets used in this paper are available online, as described in the methodology section.

References

Tirendi, S. et al. Colorectal cancer and therapy response: a focus on the main mechanisms involved. Front. Oncol. 13, 1208140 (2023).

Colombel, J. F., Shin, A. & Gibson, P. R. AGA clinical practice update on functional Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: expert review. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17(3), 380–390 (2019).

González-Puga, C., Palomeque-Jiménez, A., García-Saura, P. L., Pérez-Cabrera, B. & Jiménez-Ríos, J. A. Colonic tuberculosis mimicking Crohn’s disease: an exceptional cause of massive surgical rectal bleeding. Méd. Mal. Infect. 45(1–2), 44–46 (2015).

Rock, C. L. et al. American Cancer society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. Cancer J. Clin. 70(4), 245–271 (2020).

Bertagnolli, M. M., Mahmoud, N. N. & Daly, J. M. Surgical aspects of colorectal carcinoma. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 11(4), 655–677 (1997).

Anand, U. et al. Cancer chemotherapy and beyond: Current status, drug candidates, associated risks and progress in targeted therapeutics. Genes & Diseases. (2022).

Pérez-Herrero, E. & Fernández-Medarde, A. Advanced targeted therapies in cancer: drug nanocarriers, the future of chemotherapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 93, 52–79 (2015).

Scarini, J. F. et al. Potential role of the Eph/ephrin system in colorectal cancer: emerging druggable molecular targets. Front. Oncol. 14, 1275330 (2024).

Dienstmann, R., Salazar, R. & Tabernero, J. Overcoming resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educational Book. 35(1), e149–e156 (2015).

Yang, Y., Li, S., Wang, Y., Zhao, Y. & Li, Q. Protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in malignant tumors: molecular mechanisms and future perspective. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 7(1), 329 (2022).

Kung, C. P., Maggi, L. B. Jr & Weber, J. D. The role of RNA editing in cancer development and metabolic disorders. Front. Endocrinol. 9, 762 (2018).

Tufail, M. & Wu, C. Targeting the IGF-1R in prostate and colorectal cancer: reasons behind trial failure and future directions. Therapeutic Delivery. 13(3), 167–186 (2022).

Anand, P., Soni, S. & Padwad, Y. S. Targeted Molecular Therapies in Cancer. Mod. Cancer Ther. Tradit. Med. An Integr59–101 (Approach to Combat Cancers, 2021).

La Thangue, N. B. & Kerr, D. J. Predictive biomarkers: a paradigm shift towards personalized cancer medicine. Nat. Reviews Clin. Oncol. 8(10), 587–596 (2011).

Menyhárt, O. & Győrffy, B. Multi-omics approaches in cancer research with applications in tumor subtyping, prognosis, and diagnosis. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 949–960 (2021).

Nogimori, T. et al. ABCE1 acts as a positive regulator of exogenous RNA decay. Viruses 12(2), 174 (2020).

Sun, L., Ding, X. & Kang, Y. J. ABCE1 selectively promotes HIF-1α transactivation of angiogenic gene expression. J. Trace Elem. Med Biol. 80, 127307 (2023).

Li, S. et al. Mouse ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters conferring multi-drug resistance. Anti-Cancer agents in medicinal chemistry (Formerly current medicinal chemistry-Anti-Cancer agents) 15(4), 423–432 (2015).

Rowley, J. W., Weyrich, A. S. & Bray, P. F. The platelet transcriptome in health and disease. In Platelets (139–153). Academic. (2019).

Ren, Y., Li, Y. & Tian, D. Role of the ABCE1 gene in human lung adenocarcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 27(4), 965–970 (2012).

Hlaváč, V. et al. The expression profile of ATP-binding cassette transporter genes in breast carcinoma. Pharmacogenomics 14(5), 515–529 (2013).

Chu, P. Y., Tzeng, Y. D. T., Tsui, K. H., Chu, C. Y. & Li, C. J. Downregulation of ATP binding cassette subfamily a member 10 acts as a prognostic factor associated with immune infiltration in breast cancer. Aging (albany NY). 14(5), 2252 (2022).