Abstract

We report doping-dependent charge trapping in WS2 field-effect transistors fabricated on a 300 mm wafer. In particular, higher n-type doping–associated with smaller channel areas–correlates with an increased density of active defects. This behavior explains the asymmetric threshold voltage degradation observed in large-area ambipolar devices, where the n-branch consistently shifts more than the p-branch under gate bias stress (by a factor of ~ 3). Through electrical characterization and photoluminescence mapping, we attribute this asymmetry to process-induced inhomogeneities in the WS2 layer and its chemical environment, which lead to enhanced n-type doping at the channel center relative to the edges. The non-uniform doping profile and conduction of the 2D channel are then captured using an equivalent circuit model that quantitatively reproduces the observed degradation asymmetry and corroborates our interpretation. These results have important implications for the development of large-scale 2D semiconductor transistors, highlighting the impact of unintentional process-induced doping and channel heterogeneity on device performance and reliability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the performance of as-fabricated two-dimensional field-effect transistors (2D FETs) has advanced considerably in recent years1,2,3,4,5, most prototypes still exhibit poor threshold voltage stability and significant long-term degradation6,7,8,9,10,11. This is primarily due to a high density of defects in the gate oxide, which can trap or release charge carriers and electrostatically disturb the current flow along the channel12,13. To mitigate these issues, novel dielectric materials are investigated in combination with commonly used 2D semiconductors, aiming to engineer high-quality interfaces despite the challenges of depositing dielectrics on top of 2D van der Waals layers14,15,16,17,18.

While oxide defects are widely recognized as the main contributors to threshold voltage instability, the critical role of the 2D channel’s electrical properties is often overlooked. First, the alignment of the channel Fermi level with the energy states of the oxide defects determines whether these traps are energetically accessible to carriers12,19,20. Second, the pronounced electronic inhomogeneities commonly observed in 2D materials (Fig. 1) are expected to force carriers into preferential conduction pathways21,22,23,24, leading to spatially uneven interactions with trap states and exacerbating variability in device behavior. Finally, unintentional doping of the channel can originate from its dielectric environment. For instance, high concentrations of impurities such as carbon or hydrogen/water, as well as defects like oxygen vacancies, can create an electron-rich environment that facilitates charge transfer to the 2D channel and shifts its Fermi level25,26. At the same time, some of these chemical species have also been shown to introduce mid-gap states, potentially acting as additional charge traps10,27. A comprehensive understanding of the intricate interplay between carrier trapping, doping, and non-uniform transport–as well as the resulting degradation mechanisms such as bias temperature instability (BTI), hysteresis, and random telegraph noise (RTN)–is essential for achieving reliable device operation and advancing 2D electronics toward commercial viability.

In this work, we present a detailed analysis of the doping-dependent BTI in back-gated WS2 FETs (1–2 layers thick) fabricated on a 300 mm wafer1,28. First, we use photoluminescence (PL) spectroscopy on as-fabricated devices to correlate the transistor’s threshold voltage with the excitonic and trionic peak features of WS2, and to map spatial inhomogeneities in the channel’s electronic properties. Second, we investigate the BTI-induced threshold voltage shift as a function of stress gate voltage, stress duration, and device dimensions. Third, we compare the threshold voltage shifts in the n- and p-branches (Vt,n and Vt,p, respectively) of large-area ambipolar devices under identical stress conditions, consistently observing an asymmetry across all examined samples (i.e., ∣ΔVt,n∣ > ∣ΔVt,p∣). Finally, we employ an equivalent circuit model based on a transistor network to emulate the 2D channel inhomogeneities revealed by PL mapping and to explain the systematically larger Vt,n shifts relative to Vt,p29. Our findings indicate that higher n-type doping levels are associated with an increased number of active traps. As a result, carriers interact with more defects along the n-doped domains that form the electron conduction path, leading to stronger degradation in the n-branch. Overall, these results advance the understanding of how charge trapping, doping, and channel non-uniformities affect the performance and long-term stability of 2D FETs.

Results

Dependence of doping level on channel area

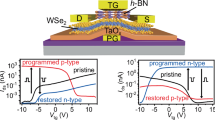

The transfer characteristics of 300-mm-integrated WS2 FETs (Fig. 2a) with varying channel lengths (Lch) and widths (Wch) exhibit a pronounced dependence of threshold voltage on device dimensions (Fig. 2b). Specifically, smaller channel areas (Ach) yield increasingly negative threshold voltages, indicative of enhanced n-type doping. This behavior is unusual and cannot be explained by simple geometrical considerations. In conventional scaling, transistors with narrower Wch are expected to exhibit the same width-normalized current density, and devices with shorter Lch should display higher current but similar threshold voltage (i.e., ID ∝ Wch/Lch), provided that short-channel effects do not occur (Lch ≳ 100 nm). Since this is not the case for our devices, we attribute the threshold voltage dependence on Ach to process-induced dopant inhomogeneity across FETs of different sizes30,31. Notably, because a uniform WS2 layer is grown and capped across the wafer prior to any device patterning (see the “Methods” section), the observed doping variability likely does not stem from the growth or capping process, but instead arises during or after active patterning (e.g., due to water intercalation32).

Another key observation emerging from Fig. 2b is that WS2 FETs with large-area channels (Lch, Wch ≳ 10 μm) not only exhibit more positive threshold voltages but also display ambipolar behavior. At negative gate biases, the Fermi level shifts toward the valence band maximum (VBM), resulting in hole accumulation and the emergence of a p-type conduction branch. Conversely, positive gate voltages shift the Fermi level toward the conduction band minimum (CBM), leading to electron accumulation and the appearance of the n-branch. In the case of small-area devices, the threshold voltage becomes so negative that the p-branch falls outside the measurement window.

The dependence of channel doping on Ach is further supported by PL characterization of the WS2 channels. PL maps of three devices with different channel areas (Wch × Lch = 75 × 30.2, 10 × 10.2, and 10 × 2.2 μm2) are acquired by stepping the laser across the channel (step size = 0.5 μm) and measuring a PL spectrum at each position. As shown in the representative spectra in Fig. 3, the characteristic PL emission of WS2 appears just below 2 eV and consists of two convoluted signals arising from the recombination of negatively charged (trion, A−) and neutral (A) excitons33,34. Since their individual contributions are too closely spaced in energy to be meaningfully deconvoluted, each spectrum is fitted with a single Voigt profile. As the channel area decreases, the PL peak broadens and shifts to lower energies due to the increasing contribution of the A− component, indicative of a higher electron density in the channel (i.e., more n-doped)31,35,36. This observation confirms the dependence of n-type doping on Ach previously inferred from electrical characterization.

Photoluminescence spectra collected at the center of three WS2 FETs with different channel areas. As the channel area decreases, the WS2 emission becomes broader and shifts to lower energies due to the enhanced trion contribution, indicative of larger electron concentration and higher n-type doping.

The extracted peak position and full width at half maximum (FWHM) are then mapped as a function of position across the channel (Fig. 4), revealing two distinct patterns of doping inhomogeneities within the individual devices. In the 10 × 10.2 and 10 × 2.2 μm2 FETs, the PL peak shifts to lower energies near the source and drain edge contacts, indicating localized regions of enhanced electron density in the vicinity of the metal interfaces. In contrast, the 75 × 30.2 μm2 device exhibits non-uniform electronic properties along the channel width, with significantly broader and slightly lower-energy PL emission at the channel center compared to the edges, indicating higher n-type doping in the central region.

a PL peak position maps and b PL peak FWHM maps collected from three WS2 FETs with varying channel areas. Again, as the channel area decreases, the PL emission becomes broader and shifts to lower energies, indicating an increased electron concentration in the channel (i.e., higher n-type doping). Additionally, the maps reveal enhanced n-type doping near the edge metal contacts in the 10 × 10.2 and 10 × 2.2 μm2 devices, and a non-uniform doping profile along the channel width in the 75 × 30.2 μm2 device.

To gather more detailed information about the dependence of the exciton/trion peak properties on doping level and Ach while avoiding time-consuming full PL mapping, we collect single-point PL spectra at the centers of devices with 15 different channel areas (same as in Fig. 2b). For each Ach, we measure the ID-VBGn-branch of eight distinct FETs using a narrow VBG sweep range to minimize trapping effects (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, Vt,n for large-area devices is minimally affected by the gate bias range, as little to no variation is observed compared to the transfer characteristics in Fig. 2b. In contrast, narrow-range ID-VBG curves of small-area devices exhibit significantly more positive Vt,n compared to wide-range sweeps, indicating substantial carrier trapping at negative gate biases. The narrow-range sweeps also reveal a clear difference in subthreshold swing (SS) between small and large devices, with small FETs exhibiting significantly steeper transfer characteristics than large ones (~ 0.9 V/dec and ~ 2.6 V/dec for the smallest and largest devices, respectively). This observation indicates that large devices have a higher density of fast and active interface traps near the WS2 CBM compared to small ones.

a ID-VBG curves measured from 120 devices with 15 different channel sizes using an adaptive single sweep from ~ − 3 V to ~ 5-10 V. b Representative EKV model fitting for four devices. c Correlation between Vt,n and the PL signal from WS2 (energy position and FWHM). As the threshold voltage decreases (i.e., n-type doping increases), the PL peak broadens and shifts to lower energies, consistent with a higher electron concentration in the channel.

Due to the markedly different shapes of the ID-VBG curves across device sizes–and the electronic inhomogeneities observed in the largest device, which introduce uncertainty in current normalization–we employ a heuristic Enz-Krummenacher-Vittoz (EKV) model fitting to robustly extract Vt,n37. An example model fit, along with a box plot of Vt,n versus PL peak position and FWHM, is shown in Fig. 5b, c. For large-area devices with positive threshold voltages, the channel is depleted, the carrier density is near zero, and the exciton/trion peaks (higher energy and narrower FWHM) remain relatively unaffected by Vt,n. However, for small-area devices with lower Vt,n, electrons accumulate in the channel, and the exciton/trion peaks (lower energy and wider FWHM) become highly sensitive to small variations in threshold voltage.

Analysis of doping-dependent BTI

To investigate size-dependent and doping-dependent trapping effects, we evaluate BTI across 120 FETs with varying channel areas by applying different stress gate biases (\({V}_{{\rm{BG,str}}}\)) for various durations (\({t}_{{\rm{str}}}\)) and monitoring the resulting shifts in Vt,n (Fig. 6a). To assess degradation recovery, the same approach is used after removing the applied stress (VBG,rel = 0 V). A small drain bias (VD = 0.1 V) is applied throughout the entire experiment, including both stress and recovery phases. The variation of charged defect density projected at the channel interface can be calculated as follows8:

where ε0 is the vacuum permittivity, \({\varepsilon }_{{{\rm{SiO}}}_{{\rm{2}}}}\) is the silica dielectric constant, q is the elementary charge absolute value, and \({\rm{EOT}}={t}_{{{\rm{SiO}}}_{{\rm{2}}}}=50\) nm is the thickness of the bottom SiO2 layer. As shown in Fig. 6b, the extracted ΔNot (eq. (1)) versus \(| {V}_{{\rm{BG,str}}}| /{t}_{{{\rm{SiO}}}_{{\rm{2}}}}\) at \({t}_{{\rm{str}}}=1\) ks exhibits the expected power-law dependence under all conditions tested. Notably, devices with smaller channel areas show significantly larger Vt,n shifts following both negative and positive gate bias stresses (NBTI and PBTI, respectively). Since equal ΔVt,n would be expected if the trap distribution were constant with device dimensions, this finding suggests that higher n-type doping is correlated with a larger number of active defects within the Fermi level window scanned under stress, resulting in enhanced degradation. This is further confirmed by the plot of ΔVt,n versus the initial threshold voltage of the as-fabricated device (Vt,n,0) in Fig. 6c, where monotonically increasing degradation is observed with decreasing Vt,n,0 across all NBTI stress conditions (\({t}_{{\rm{str}}}=1\) ks). The same trend is also consistent with the substantial threshold voltage differences observed between wide- and narrow-range ID-VBG sweeps in small-area devices (Fig. 2b and Fig. 5a, respectively), which arise from strong trapping effects at negative gate biases.

a ID-VBG curves measured during the stress phase (\({V}_{{\rm{BG}},{\rm{str}}}=25\,{\rm{V}}\)) and subsequent recovery phase (VBG,rel = 0 V) for two devices with different channel areas. b Extracted ΔNot plotted as a function of \(| {V}_{{\rm{BG,str}}}| /{\rm{EOT}}\) at \({t}_{{\rm{str}}}=1\,{\rm{ks}}\) for both NBTI and PBTI stress conditions. c Experimental negative bias-induced ΔVt,n as a function of the initial threshold voltage Vt,n,0. Devices with higher n-type doping (i.e., smaller channel area) exhibit more pronounced degradation.

To comprehensively assess bias-induced degradation in ambipolar WS2 FETs, we extend our BTI investigation to both conduction branches of large-area devices (Lch = 30.2 μm and Wch = 75 μm) by tracking ΔVt,n and ΔVt,p under NBTI and PBTI stress. As shown in Fig. 7, the resulting threshold voltage shifts exhibit a consistent asymmetry across all devices and bias conditions, with the n-branch systematically shifting more than the p-branch. To explain this peculiar behavior, we rule out both uniform charge trapping across the device area–which would be expected to have the same electrostatic impact on both conduction branches, causing a symmetric shift–and the formation of deep, fast defects under stress, which could charge or discharge during the VBG sweep. If such defects were present, a larger ΔVt,n would appear only for positive bias stresses. This is because sweeping VBG from negative to positive values–corresponding to the Fermi level shift toward the CBM–would result in a net negative variation of the trapped charge, introducing an extra positive ΔVt,n contribution after both positive and negative BTI stresses. Consequently, the negative NBTI-induced shifts in the n-branch would be smaller than those in the p-branch, contrary to our experimental observations.

Instead, we attribute the asymmetric BTI to significant heterogeneity in the electronic properties of the deposited WS2 channels, as highlighted by the PL map in Fig. 4. If the WS2 band gap is assumed to be constant across the device area, electrons and holes are expected to preferentially travel through the center and the edges of the channel, respectively, due to the uneven doping profile. In other words, the large-area device is expected to behave as two parallel ambipolar transistors: the more n-doped center region, with lower ∣Vt,n∣, controls the n-branch, while the less n-doped edges, with lower ∣Vt,p∣, control the p-branch (Fig. 8a). As a result, each carrier type may interact with a different distribution of defects along its path. In our case, since stronger n-type doping is correlated with a higher defect density (Fig. 6), this scenario is consistent with the greater degradation observed in the n-branch due to larger charge trapping at the channel center compared to its edges (as schematically shown in Fig. 8b).

a Schematic illustration of the ambipolar transfer characteristics of an as-fabricated WS2 FET with a non-uniform doping profile along the channel width. The channel center, exhibiting higher n-type doping, controls the n-branch, while the channel edges, exhibiting lower n-type doping, control the p-branch. b Schematic illustration of the degraded transfer characteristics of the same device after negative bias stress. A larger shift of the n-branch relative to the p-branch arises due to the increasing density of active traps with higher n-type doping levels.

FET network modeling

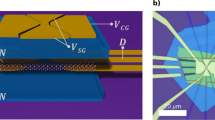

To better quantify the impact of channel inhomogeneities on transport and BTI, we reproduce the degradation asymmetry using an equivalent circuit model based on a 150 × 60 FET-connected network in a SPICE simulator (same aspect ratio as the investigated WS2 75 × 30.2 μm2 channels)29. The overall workflow for constructing the FET network model is illustrated in Fig. 9. Each node is connected both vertically and horizontally by a parallel Si-based pFET and nFET with a thick gate dielectric (50 nm SiO2), all sharing the same gate voltage to replicate the ambipolar behavior of our WS2 devices (Fig. 10a). The transport direction is defined by connecting the first and last transistor rows to the source (VS = 0 V) and drain (VD = 0.1 V), respectively. To emulate the width-dependent doping profile observed in the PL map in Fig. 4, we convert the PL peak’s FWHM into Vt,n by fitting the data in Fig. 5c with an exponential function of a second-order polynomial, which closely follows the experimental trend. The resulting Vt,n distribution is then incorporated into the equivalent circuit model by assigning each value from the converted map to the corresponding node in the FET network (Fig. 10a). For simplicity, the difference between Vt,n and Vt,p in each FET pair is set to 8 V (i.e., Vt,p = Vt,n − 8 V, consistent with the experimental data), implying that the channel band gap is assumed constant across the entire device. When a positive gate voltage is applied to the FET network, electrons preferentially flow through nFET paths with lower threshold voltages along the channel center (Fig. 10b). Conversely, under negative gate bias, holes flow through pFET paths with lower threshold voltages along the channel edges (Fig. 10c). This model effectively captures the non-uniform transport mechanism in an ambipolar large-area FET with a spatially varying doping profile.

Workflow for constructing the 150 × 60 FET network model. The PL FWHM map of the large-area WS2 FET is converted into a spatial Vt,n map using an exponential function derived from single-point PL FWHM vs. Vt,n measurements. This Vt,n distribution serves as input to the network model, together with an additional exponential relation describing ΔVt,n as a function of the initial Vt,n,0, which is required to reproduce the asymmetric degradation resulting from non-uniform charge trapping.

a Schematic of the 150 × 60 FET-connected network implemented in a SPICE simulator to model non-uniform transport and asymmetric degradation in large-area WS2 FETs. The Vt,n distribution is derived by converting the PL map in Fig. 4 using the exponential fitting function shown in Fig. 5. b Simulated electron current distribution at VBG = 7 V, illustrating preferential conduction through the channel center, where ∣Vt,n∣ is lower (i.e., higher n-type doping). c Simulated hole current distribution at VBG = − 8.5 V, showing that holes flow mainly through the channel edges, where ∣Vt,p∣ is lower (i.e., lower n-type doping).

We now evaluate the asymmetric bias-induced degradation caused by non-uniform charging across the device area (Fig. 11). To this end, we consider the case of NBTI under four stress gate biases (− 10, − 15, − 20, and − 25 V) and a stress time of 1 ks. As discussed in the previous paragraphs, a higher n-type doping level (i.e., a lower Vt,n) results in greater degradation of the 2D FET. To transfer this information into the FET network model, we perform a global fit of the degradation traces in Fig. 6c with an exponential function, using the same exponent and separate fitted coefficients for each stress bias to reduce the number of free parameters. Next, we simulate the transfer characteristics of the FET network using the Vt,n distribution extracted from PL mapping. For each NBTI stress bias, we repeat the simulation by applying a stress-induced threshold voltage shift to each FET pair, assuming ΔVt,n = ΔVt,p, as each node represents a uniform region where trapped charges exert the same electrostatic impact on both conduction branches. The applied shifts are exponentially proportional to the initial Vt,n values, as extracted from the fit in Fig. 6c. As a result, an empirical ΔVt,n distribution–reflecting both the spatially varying Vt,n and the doping-dependent degradation–is incorporated into the equivalent circuit model. In summary, rather than modeling the physical trapping mechanisms explicitly, our approach uses the experimentally measured correlation between doping and degradation to assign local threshold voltage shifts.

A comparison of the fresh and degraded transfer characteristics of the FET network is shown in Fig. 11a. The model successfully replicates the asymmetric degradation across all stress conditions, with the n-branch consistently exhibiting a greater shift than the p-branch. Although the FET network model does not aim to describe the full physical and electrostatic behavior of a 2D FET, the simulated ΔVt,n and ΔVt,p show good agreement with experimental results (Fig. 11b), indicating that the electrostatic shift induced by a non-uniform distribution of charges (extracted from experiments) can be captured with sufficient accuracy. In particular, while the model slightly overestimates degradation at high stress biases, it correctly reproduces the asymmetry magnitude in all tested cases.

Compared to CPU-intensive 3D TCAD simulations, our equivalent circuit approach offers a fast and flexible framework to evaluate the effects of spatial variability in large-area devices. However, its scope remains qualitative–or at best semi-quantitative, as demonstrated in this work–since it does not capture full electrostatics or quantum effects at the nanoscale. Therefore, the FET network provides a simplified, easy-to-use tool to corroborate our hypotheses, rather than serving as a replacement for significantly more accurate and rigorous TCAD modeling. Because several electrical parameters of each node’s FET can be arbitrarily adjusted, our model is also readily extendable to other phenomena involving spatial variability, such as non-uniform mobility or interface trap density.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that n-doped regions are associated with a substantially higher density of active defects, contributing to the reduced stability of the ID-VBGn-branch observed in our devices. This scenario is plausible given the well-established sensitivity of 2D TMDs’ electronic properties to their chemical environment. In this context, several studies have shown that defects in the gate dielectric (e.g., oxygen vacancies and undercoordinated Al atoms), defects in the channel (e.g., sulfur vacancies), and adsorbates on the TMD surface (e.g., water molecules) play a critical role in modulating local doping25,32,38,39. These same defects also introduce localized energy states within the band gap, potentially acting as carrier traps. As a result, spatial variations in doping are likely correlated with the spatial distribution of active traps. Furthermore, the enhanced stability of the p-branch aligns with our previous study on 300-mm-integrated 2D FETs with the same gate stack but different channel materials, where WSe2 pFETs exhibited significantly greater reliability than MoS2 and WS2 nFETs40. This further supports the notion that, in our 300-mm-integrated devices, n-type doping is associated with a higher trap density than p-type doping. Nonetheless, a comprehensive comparison remains challenging due to the limited availability of reliability studies on 2D pFETs.

In line with these observations, the occurrence of defects acting simultaneously as dopants and charge traps may not be unique to the WS2 FETs discussed here. Similar channel-area-dependent doping effects have been observed in our 300-mm integrated MoS2 FETs, featuring substantially larger crystal domains and higher channel mobility (>100 μm and 20–50 cm2/V ⋅ s, respectively, compared to the ~ 100 nm domains and ~ 3 cm2/V ⋅ s mobility of the WS2 channels investigated here)28,30,31. This suggests that the chemical species highlighted in this work–such as intercalated water, oxygen vacancies, undercoordinated Al atoms, and sulfur vacancies–could influence the stability of a broad range of 2D FETs.

While variations in impurity/defect concentrations–responsible for both n-type doping and charge trapping–can explain the greater degradation observed in smaller devices compared to larger ones, the origin of these variations, as well as the inhomogeneous doping profile along the channel width in large-area FETs, remains unclear. If the doping variability were caused by contact formation (e.g., via diffusion of impurities from the metal contacts), one would expect a non-uniform profile along the channel length of large-area devices. However, since the observed heterogeneity occurs along the channel width, it is more likely introduced during the patterning step of device fabrication (e.g., water intercalation32).

Looking ahead, as fabrication processes advance toward highly scaled devices with channel lengths and widths on the order of 10 nm, improved process control is expected to mitigate unintentional doping effects, which is essential to reduce threshold voltage variability. While the micrometer-scale inhomogeneities observed in our current devices may become less relevant in these future generations, nanoscale fluctuations in the electronic properties of TMDs are likely to remain a key factor affecting device reliability21,22,23,24. For instance, in scaled ambipolar 2D FETs, degradation asymmetries could still occur, as electrons and holes may traverse different percolation paths subject to distinct defect types and trap densities.

Collectively, these results provide crucial insights into the intricate interplay between charge trapping, channel doping, and channel inhomogeneities, highlighting their critical impact on the performance and long-term stability of WS2 FETs. While n-type doping increases the density of defects that are active during BTI stress, the inhomogeneous doping profile observed in large-area WS2 FETs leads to asymmetric degradation of their ambipolar transfer characteristics. Future studies focused on understanding the relationship between defects and the electronic properties of 2D channels will be crucial for optimizing both the performance and reliability of 2D material-based devices, ultimately enabling their use in practical electronic applications.

Methods

Device fabrication

All devices are fabricated in a 300 mm pilot line1,28. The WS2 channel (1–2 layers) is grown by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition from W(CO)6 and H2S precursors at 750 ∘C directly on the 50 nm SiO2 back-gate oxide. It is then capped with ~ 1 nm AlOx deposited at 100 ∘C (5 cycles of TMA soak followed by oxidation with H2O pulses), which enables the subsequent deposition of 10 nm HfO2 by atomic layer deposition (ALD) at 350 ∘C. After active patterning, the channels are encapsulated with SiO2 (PECVD) ILD0. Source and drain contacts are defined using a damascene process: contact trenches are etched and filled with Ti/TiN/W (TiN by ALD at 380 ∘C), followed by CMP planarization. The perimeter of the side contacts encompasses the entire contact pads (80 μm × 60 μm).

The investigated devices feature channel lengths Lch of 30.2 μm, 20.2 μm, 10.2 μm, 5.2 μm, and 2.2 μm, and channel widths Wch of 75 μm, 30 μm, and 10 μm.

Experimental methods and simulations

All electrical measurements are performed using a Süss PA300 probe station equipped with two Keithley 2636B source-meters and a Thermochuck, controlled over GPIB from a PC using a framework of Perl subroutines.

PL spectra are collected at room temperature on a Horiba Scientific LabRAM HR spectrometer using 532 nm excitation through a 100 ×, 0.9 NA objective, yielding a ~ 1 μm spot size and a laser power density of ~ 0.3 mW/μm2. The laser penetrates the transparent top dielectric stack (300 nm SiO2, 10 nm HfO2, 1 nm AlOx), reaches the WS2 channel, and generates its photoluminescence response. The emitted and scattered light is collected via the same objective, dispersed by a 300 g/mm grating, and detected with an open-electrode CCD, with a typical integration time of 10 s. Peak parameters are extracted using Fityk software.

SPICE simulations are performed using the Specter simulator (Cadence).

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality agreements with industrial partners collaborating within the imec research program. However, the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Asselberghs, I. et al. Wafer-scale integration of double gated ws2-transistors in 300mm si CMOS fab. In 2020 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) (IEEE, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/iedm13553.2020.9371926.

Wu, R. et al. Bilayer tungsten diselenide transistors with on-state currents exceeding 1.5 milliamperes per micrometre. Nat. Electron. 5, 497–504 (2022).

Li, W. et al. Approaching the quantum limit in two-dimensional semiconductor contacts. Nature 613, 274–279 (2023).

Jiang, J., Xu, L., Qiu, C. & Peng, L.-M. Ballistic two-dimensional inse transistors. Nature 616, 470–475 (2023).

Jiang, J. et al. Yttrium-doping-induced metallization of molybdenum disulfide for ohmic contacts in two-dimensional transistors. Nat. Electron. 7, 545–556 (2024).

Illarionov, Y. Y. & Grasser, T. Reliability of 2d field-effect transistors: from first prototypes to scalable devices. In 2019 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Physical and Failure Analysis of Integrated Circuits (IPFA), 1–6 (2019).

Illarionov, Y. Y. et al. Insulators for 2d nanoelectronics: the gap to bridge. Nature Commun.11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16640-8 (2020).

Panarella, L. et al. Analysis of bti in 300 mm integrated dual-gate ws2 fets. In 2022 Device Research Conference (DRC), 1–2 (2022).

Knobloch, T. et al. Improving stability in two-dimensional transistors with amorphous gate oxides by fermi-level tuning. Nat. Electron. 5, 356–366 (2022).

Panarella, L. et al. Experimental-modeling framework for identifying defects responsible for reliability issues in 2d fets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 62314–62325 (2024).

Lan, H.-Y. et al. Reliability of high-performance monolayer mos2 transistors on scaled high-κ hfo2. npj 2D Materials and Applications 9, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00527-7 (2025).

Kaczer, B. et al. A brief overview of gate oxide defect properties and their relation to mosfet instabilities and device and circuit time-dependent variability. Microelectron. Reliab. 81, 186–194 (2018).

Grasser, T. Stochastic charge trapping in oxides: From random telegraph noise to bias temperature instabilities. Microelectron. Reliab. 52, 39–70 (2012).

Illarionov, Y. Y. et al. Ultrathin calcium fluoride insulators for two-dimensional field-effect transistors. Nat. Electron. 2, 230–235 (2019).

Grasser, T., Waltl, M. & Knobloch, T. Fluoride dielectrics for 2d transistors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 880–881 (2024).

Kang, T. et al. High-κ dielectric (hfo2)/2d semiconductor (hfse2) gate stack for low-power steep-switching computing devices. Advanced Materials 36, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202312747 (2024).

Khakbaz, P. et al. Two-dimensional bi2seo2 and its native insulators for next-generation nanoelectronics. ACS Nano 19, 9788–9800 (2025).

Sattari-Esfahlan, S. M. et al. Stability and reliability of van der waals high-κ srtio3 field-effect transistors with small hysteresis. ACS Nano 19, 12288–12297 (2025).

Arimura, H. et al. Ge nfet with high electron mobility and superior pbti reliability enabled by monolayer-si surface passivation and la-induced interface dipole formation. In 2015 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 21.6.1–21.6.4 (2015).

Lan, H.-Y., Oleshko, V. P., Davydov, A. V., Appenzeller, J. & Chen, Z. Dielectric interface engineering for high-performance monolayer mos2 transistors via taox interfacial layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 70, 2067–2074 (2023).

Addou, R. et al. Impurities and electronic property variations of natural mos2 crystal surfaces. ACS Nano 9, 9124–9133 (2015).

Kaushik, V., Varandani, D. & Mehta, B. R. Nanoscale mapping of layer-dependent surface potential and junction properties of cvd-grown mos2 domains. J. Phys. Chem. C. 119, 20136–20142 (2015).

Moore, D. et al. Uncovering topographically hidden features in 2d mose2 with correlated potential and optical nanoprobes. npj 2D mater. appl.4, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-00178-w (2020) .

Panarella, L. et al. Evidence of contact-induced variability in industrially-fabricated highly-scaled mos2 fets. npj 2D Materials and appl 8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-024-00482-9 (2024).

Leonhardt, A. et al. Material-selective doping of 2d tmdc through alxoy encapsulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11, 42697–42707 (2019).

McClellan, C. J., Yalon, E., Smithe, K. K. H., Suryavanshi, S. V. & Pop, E. High current density in monolayer mos2 doped by alox. ACS Nano 15, 1587–1596 (2021).

Dicks, O. A., Cottom, J., Shluger, A. L. & Afanas’ev, V. V. The origin of negative charging in amorphous al2o3 films: the role of native defects. Nanotechnology 30, 205201 (2019).

Schram, T., Sutar, S., Radu, I. & Asselberghs, I. Challenges of wafer-scale integration of 2d semiconductors for high-performance transistor circuits. Advanced Materials 34, (2022). https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202109796.

Kaczer, B. et al. The relevance of deeply-scaled fet threshold voltage shifts for operation lifetimes. In 2012 IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS), 5A.2.1–5A.2.6 (2012).

Ghosh, S. et al. Integration of epitaxial monolayer mx2 channels on 300mm wafers via collective-die-to-wafer (cod2w) transfer. In 2023 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits), 1–2 (2023).

Nuytten, T. et al. Toward characterization and assessment of mos2 fundamental device properties by photoluminescence. Mater. Sci. Semiconductor Process. 193, 109489 (2025).

Serron, J. et al. Conductivity enhancement in transition metal dichalcogenides: A complex water intercalation and desorption mechanism. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 26175–26189 (2023).

Shi, W. et al. Raman and photoluminescence spectra of two-dimensional nanocrystallites of monolayer ws2 and wse2. 2D Mater. 3, 025016 (2016).

Sebait, R., Biswas, C., Song, B., Seo, C. & Lee, Y. H. Identifying defect-induced trion in monolayer ws2 via carrier screening engineering. ACS Nano 15, 2849–2857 (2021).

Mak, K. F. et al. Tightly bound trions in monolayer mos2. Nat. Mater. 12, 207–211 (2012).

Golovynskyi, S. et al. Trion binding energy variation on photoluminescence excitation energy and power during direct to indirect bandgap crossover in monolayer and few-layer mos2. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 17806–17819 (2021).

Dei, M. Heuristic enz–krummenacher–vittoz (ekv) model fitting for low-power integrated circuit design: An open-source implementation. Electronics 14, 1162 (2025).

Van Troeye, B. et al. Impact of interface and surface oxide defects on ws2 electronic properties from first principles. ACS Nano 19, 11664–11674 (2025).

Lu, H., Kummel, A. & Robertson, J. Passivating the sulfur vacancy in monolayer mos2. APL Materials 6, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5030737 (2018).

Dorow, C. J. et al. Exploring manufacturability of novel 2d channel materials: 300 mm wafer-scale 2d nmos & pmos using mos2, ws2, & wse2. In 2023 International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM), 1–4 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO, grant no. 1S72625N) and funded by the imec IIAP Exploratory Logic program, the 2D-PL pilot line project through Horizon Europe (grant no. 101189797), and Horizon 2020 (grant no. 952792).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.P. performed the electrical measurements, the modeling, and wrote the manuscript. B.K., Q.S., and V.A. supervised the research. T.N. performed the PL measurements. Q.S., C.L.R., and G.S.K. contributed to the development of imec 300 mm FAB process. B.V.T., S.T., P.S.C., and T.G. contributed to the development of the equivalent circuit model. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Panarella, L., Kaczer, B., Smets, Q. et al. Impact of doping and channel inhomogeneities on the stability of industrially fabricated WS2 FETs. npj 2D Mater Appl 10, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00644-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00644-3