Abstract

Tissue clearing combined with high-resolution confocal imaging is a cutting-edge approach for dissecting the three-dimensional (3D) architecture of tissues and deciphering cellular spatial interactions under physiological and pathological conditions. Deciphering the spatial interaction of leptin receptor-expressing (LepR+) stromal cells with other compartments in the bone marrow is crucial for a deeper understanding of the stem cell niche and the skeletal tissue. In this study, we introduce an optimized protocol for the 3D analysis of skeletal tissues, enabling the visualization of hematopoietic and stromal cells, especially LepR+ stromal cells, within optically cleared bone hemisections. Our method preserves the 3D tissue architecture and is extendable to other hematopoietic sites such as calvaria and vertebrae. The protocol entails tissue fixation, decalcification, and cryosectioning to reveal the marrow cavity. Completed within approximately 12 days, this process yields highly transparent tissues that maintain genetically encoded or antibody-stained fluorescent signals. The bone hemisections are compatible with diverse antibody labeling strategies. Confocal microscopy of these transparent samples allows for qualitative and quantitative image analysis using Aivia or Bitplane Imaris software, assessing a spectrum of parameters. With proper storage, the fluorescent signal in the stained and cleared bone hemisections remains intact for at least 2–3 months. This protocol is robust, straightforward to implement, and highly reproducible, offering a valuable tool for tissue architecture and cellular interaction studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Adult bone marrow leptin receptor-expressing stromal cells (LepR+ cells) secrete key growth factors to maintain hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 whereas they themselves give rise to bone and fat.11,12,13 Recent single-cell RNA-sequencing studies suggest that LepR+ cells are heterogeneous especially under stress and include skeletal stem cells, osteogenic progenitors, adipogenic progenitors, fibroblasts, etc.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24 Unraveling the spatial interaction of LepR+ stromal cells with other compartments in the bone marrow, such as the endothelium or the hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, will shed light on our understanding on the skeletal tissue. Currently, however, there are few markers available to separate these subpopulations in situ and lack of a reliable monoclonal antibody for these cells, thus hindering further investigations of their specific functions.25,26,27,28

To identify the locations of these subpopulations of LepR+ cells, we developed a tissue clearing protocol that enables immunofluorescence visualization of mouse bone marrow in three dimensions by making the tissue transparent.4,9,29 In this protocol, we described how to prepare opaque organs and tissues of interest (here, we use mostly mouse long bones as examples), stain the tissue with fluorescence-conjugated antibodies, and obtain the distribution pattern of distinct cell populations (here, mostly LepR+ cells, endothelial cells, or their subsets) in three dimensions after optical clearance. We previously have used this approach to demonstrate that the Osteolectin-expressing subset of LepR+ cells (Osteolectin+ cells) resides exclusively in a peri-arteriolar location4 and that nerve growth factor (NGF) is primarily synthesized by the perivascular LepR+ cells.9 Here, we now modified this approach to be more cost-efficient and less time-consuming to image various stromal cell populations in bone marrow and further adapted this protocol to investigate other cell populations in bone marrow or other perivascular or vascular cells across diverse mammalian tissues, such as the spleen and lung.

Results

Overview of the modified workflow for the deep imaging technique

High-resolution visualization of rare cell populations throughout an entire organ can enhance our understanding of their spatial distribution, interactions, and functions. We developed a deep imaging method to visualize LepR+ cells and hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells in bone marrow from the long bones of adult genetic reporter mice primarily with antibodies targeting tdTomato (tandem dimer Tomato) and GFP (green fluorescent protein).4,29 In this article, we detail a method for optically clearing tissues post-immunofluorescence staining. The optimized process is outlined in a flowchart (Fig. 1) and a detailed procedure (Table 1). We have refined this method specifically for long bones from the mouse skeletal system and validated it with various antibodies, as listed in Table 2.

Workflow of the optimized deep imaging protocol for optically cleared skeletal tissue. Steps for preparing the deep-imaging bone hemisections, including tissue fixation, decalcification, dehydration, embedding, and cryosectioning to generate bone hemisections; and immunostaining, tissue clearing, and mounting, with subsequent imaging. BABB, benzyl alcohol/benzyl benzoate (1:2, v/v) clearing solution

In this study, we improved our blocking cocktail for cost-effectiveness and introduced an innovative, reusable platform for mounting optically cleared bone hemisections (Fig. S1). We reduced the blocking time, streamlining the sample preparation for imaging to 11–12 days without compromising antibody binding specificity. The reusable quartz mold for bone hemisections is versatile for other tissues, ensuring better preservation of stained and cleared samples post-imaging. The protocol yields multicolor immunofluorescent images from tiled scan-stacks, at least 500 µm deep, which can be reconstructed into 3D and projected into 2D at various magnifications and depths (Fig. S2a). This approach leverages multiple transgenic mouse models to locate rare cell populations, including stem/progenitor cells in skeletal tissue, at high-resolution with detailed spatial interactions (Fig. S2b).

Method application in the long bone

Growth factors play vital roles in bone homeostasis, regeneration, and remodeling. Osteolectin, a novel bone growth factor, stimulates the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow LepR+ cells and other progenitors into osteoblasts by activating integrin α11β1 and Wnt signaling.30,31,32,33 Using our optimized imaging technique, we confirmed that Osteolectin-mTomato+ (Oln-mTomato+) cells co-localized with LepR+ cells around endomucinlow arterioles in the diaphysis (Fig. S3a). Further staining of a femur hemisection from an OlnmTomato/+ mouse with endomucin (a vascular endothelial cell marker) and SCA-1 (a bone marrow arteriolar endothelial cell marker) revealed that Oln-mTomato+ cells were specifically associated with SCA-1+endomucinlow arterioles, not with sinusoids (Fig. S3b, c). Our enhanced deep imaging method has thus facilitated the identification of peri-arteriolar Osteolectin+ cells as a rare, short-lived osteogenic progenitor population, which were reported to be mechanosensitive.4,34

Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) are rare yet crucial for blood system reconstitution, primarily residing in bone marrow niches.29,35,36,37 Their precise locations and niche interactions are of significant interest to hematopoiesis researchers. For studying these cells, we utilized intact bone marrow plugs from long bones, which offer faster processing and imaging times—approximately 1–2 days shorter than bone hemisections.38 Our optimized method revealed that HSPCs, identified as lineage−c-kit+ cells, or LK cells, were closely associated with the vasculature (Fig. 2a). Similarly, α-catulin-GFP+c-kit+ hematopoietic stem cells were found in proximity to the vasculature (Fig. 2b). Quantitative analysis showed that majority of α-catulin-GFP+c-kit+ HSCs were closer to sinusoids than arterioles or vessels in the transition zone (significantly closer than random spots; Fig. 2c), aligning with previous findings of a peri-sinusoidal HSC niche in adult bone marrow.29,39 However, the use of bone marrow plugs precludes the observation of bone surface interactions, as the calcified bone is removed during the process, which hinders the visualization of endosteal interactions with bone marrow cells, including those of lymphoid progenitors.3,40,41 Therefore, the use of bone hemisections remains essential for such studies. Using hemisections, we demonstrated that hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) were significantly further from the endosteum than would be expected by chance (Fig. 2d).

Hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells locate near the vessels in adult bone marrow. a 2D projected images of thick specimen. Lineage−c-kit+ hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells are in close proximity to blood vessels, identified by laminin (Cyan) staining. A single HSPC is indicated by an arrow in the higher magnification images. b 2D projected images of 100-µm image stacks from a cleared bone marrow plug. α-catulin-GFP+c-kit+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are similarly situated near vessels, identified by laminin (Cyan) staining, with a single HSC highlighted by an arrow in the magnified views. Quantitative analysis of the distance between HSCs and randomly selected spots to the nearest blood vessel (c) and endosteum (d). Data are representative of 7 experiments with one mouse per experiment. e 2D projected images of 50-µm image from a cleared bone hemisection. Blood vessels, identified by endomucin labeling, and LepR+ cells in young (2-month-old) and aged (20-month-old) wild-type mice, visualized after clearing with BABB. All images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment per age

Bone marrow is innervated with sympathetic,42,43,44 parasympathetic,45,46 and sensory47 nerve fibers, together with glial cells.48,49 These peripheral nerves are known to facilitate the regeneration of various tissues, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood.50,51,52 Nerve growth factor (NGF), highly expressed in adult bone marrow, is crucial for maintaining this innervation.9 To validate our optimized imaging method, we utilized NgfmScarlet/+ reporter mice to pinpoint the source of marrow NGF. We found that Ngf-mScarlet+ cells are situated around both endomucinlow arterioles and endomucinhigh sinusoids (Fig. S4a). These cells also express Scf-GFP (Fig. S4b). The peri-arteriolar cells, which include both LepR+Scf-GFP+ cells and smooth muscle actin (SMA) expressing cells, are predominantly Ngf-mScarlet+ (Fig. S4c). Peripheral nerves, despite their small volume fraction in bone marrow, are often overlooked in thin sections due to immunofluorescence staining limitations. Our method allowed us to clearly visualize peripherin+ peripheral nerve fibers along SCA-1+endomucinlow arterioles in hemisections, more efficiently and economically (Fig. S4d). This demonstrates that deep imaging is not only effective for visualizing rare cell populations like Osteolectin+ or NGF+ cells but also for capturing rare anatomic structures, such as nerve fibers, which are typically challenging to observe or quantify in standard sections.

Deep imaging applications in other skeletal tissues and in aged mice

This optimized imaging method is applicable not only to long bones from 2- to 4-month-old mice (Fig. S1–4) and previous studies,4,29 but also to long bones from aged mice (≥18 months old) and various other bones within the skeletal system. In aged mice, we observed morphological changes in the femoral endothelium, which appeared more fragmented (Fig. 2e). This protocol is thus valuable for investigating aging-related alterations within the bone marrow niche, including the escalation of inflammatory responses.53,54,55 The protocol is adaptable for any bone, including calvaria and vertebrae. When applied to bones beyond long bones, we found Oln-mTomato expression in osteoblasts on the endosteal surface and around SCA-1+endomucinlow arterioles in the pelvis and humerus (Fig. 3a, b). LepR+ cells were also identified in close association with the endothelium of the rostral rhinal veins (RRV) and the confluence of sinuses (COS) in the skull (Fig. 3c). Therefore, this protocol extends beyond long bones to encompass a wide range of skeletal tissues in mice. Troubleshooting tips for the protocol are provided in Table 3.

Application of the deep imaging protocol to various skeletal tissues. a, b In the pelvis and humerus bone marrow of 2-month-old OlnmTomato/+; Col1a1*2.3-eGFP mice, Oln-mTomato+ stromal cells are exclusively localized around SCA-1+endomucinlow arterioles (indicated by arrowheads), consistent with that observed in long bones. Second harmonic generation (SHG) is used to visualize the bone matrix. c In the skull of 2-month-old Leprcre/+; Rosa26tdTomato mice, LepR+ cells are observed in proximity to the endothelium, as marked by VE-Cadherin (blue), specifically in the confluence of sinuses (COS) and the rostral rhinal vein (RRV) regions. All images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment

Advantages and disadvantages of this method

Various methods are available for qualitative and quantitative analysis of rare cell populations in vivo. A common approach involves imaging 8–12 µm thick bone marrow sections.39 However, this technique’s main limitation is the difficulty in locating rare cell populations or sparse anatomical structures due to the reduced microscopy coverage, potentially leading to the omission of important areas like arterioles and nerve fibers.

To overcome this, imaging thicker sections, such as 50–100 µm, can increase the imaging area and partially address these limitations.56,57,58,59,60 Optical clearing of 100-µm-thick sections revealed the presence of Oln-mTomato+ cells in both trabecular and cortical bone, marking osteoblasts on bone surfaces and osteocytes within the bone (Fig. 4a, b), similar to observations in optical-cleared hemisections (Figs. S2, 3).

Characterization of bone marrow vasculature in long bones. In 100-µm-thick bone sections from 2-month-old OlnmTomato/+; Col1a1*2.3-eGFP mice, Col1a1*2.3-eGFP+ osteoblasts, which also express Oln-mTomato, were identified on both trabecular (a) and cortical (b) bone regions. c The transcortical blood vasculature within the cortical bone is visualized by endomucin staining (marked by white asterisk) in 100-µm-thick bone sections from the same mouse model. d 2D projected images of 200-µm image stack from a cleared bone hemisection. Transcortical vessels, labeled with endomucin (red), are evident in the cortical bone (blue, SHG) of the tibia from a wild-type mouse, following clearing with the BABB method. All images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment

The processing time for 100-µm-thick sections is approximately 10 days, similar to optical-cleared hemisections, but with limited spatial information. Transcortical vessels in the long bones have been only recently identified due to the limitation of imaging techniques and relative scarcity comparing to highly vascularized marrow cavity.61 Transcortical endomucin+ vessels are more frequently observed in the max projection of 200-µm image stacks from optical-cleared hemisections compared to 100-µm-thick sections (Fig. 4c, d). These vessels within the cortical bone are easily identified in 150-µm-thick sections as endomucin+ structures, with no Scf-GFP+ perivascular stromal cells surrounding them (Fig. 5a). Additionally, arterioles, which are relatively sparse in the bone marrow cavity, are discontinuous in thin sections but more clearly visualized in 50-µm-thick sections (Fig. 5b). The max projection of 150-µm image stacks from optical-cleared hemisections offers the best structural integrity and frequency of these structures (Fig. 5b). Therefore, optical-cleared hemisections provide a unique advantage for locating rare cell populations and sparse anatomical structures with high integrity.

Comparative vascular imaging at various depths in murine femurs. a Imaging sections reveals the transcortical blood vasculature (asterisk) with thickness of 10-µm-thick sections, 50-µm-thick sections, and 2D projection of 150-µm-thick image stack from cleared bone hemisections within the femur of 2-month-old ScfGFP/+ mice. b Sections of femur bone marrow from 2-month-old NgfmScarlet/+ mice, peri-arteriolar Ngf-mScarlet+ cells (arrowhead) are observed with thickness of 10 µm, 50 µm, and 2D projection of 150-µm-thick image stack from cleared bone hemisections. All images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment

Analyzing LepR+ cells in situ with a novel monoclonal antibody

We have adopted this method primarily for investigating LepR+ cells in bone marrow, which are known to include skeletal stem cells responsible for forming most bone and fat in adult bone marrow.11,12 The standard antibody used for flow cytometry and immunofluorescence in thin/thick sections is a polyclonal antibody (R&D, AF497).1,3,4,11 However, until now, no monoclonal antibody has reliably recognized endogenous LepR, limiting research on LepR-expressing cells in situ. In partnership with Abcam, we developed and characterized a novel monoclonal antibody that efficiently stains bone marrow LepR+ cells. Our validation showed that (92 ± 4.3)% of bone marrow cells labeled by this anti-LepR antibody were indeed LepR+ (as confirmed by LepRcre/+; tdTomato labeling), and (93 ± 2.0)% of LepR+ cells were detected by this monoclonal antibody (Fig. 6a, b). This was further confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of 50-µm bone sections, where anti-LepR antibody staining coincided with tdTomato+ cells in LepRcre/+; tdTomato mice (Fig. 6c). The antibody also effectively stained perivascular LepR+ cells around endomucin+ vasculature in cleared bone sections (Fig. 6d). Importantly, this antibody cross-reacts with human LepR: flow cytometric analysis of human bone marrow using this antibody indicated that approximately (0.66 ± 0.15)% of bone marrow cells were LepR+ (Fig. 6e). These LepR+ cells from human bone marrow were capable of forming colonies and differentiating into osteogenic and adipogenic lineages (Fig. 6f), consistent with the characteristics of human skeletal stem cells.62,63

Characterization of a novel monoclonal antibody against LepR. a, b Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically dissociated bone marrow cells from 2-month-old wild-type or Leprcre/+; Rosa26tdTomato mice demonstrates the identification of a putative LepR+ cell population using a novel anti-LepR antibody. The absence of this population in the FMO (Fluorescence Minus One) control confirms antibody specificity. b Anti-LepR staining overlapped with LepR+ cells identified by Leprcre/+; Rosa26tdTomato mice. Data are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment. c Immunofluorescence staining of a 50-µm-thick femur bone marrow section from a Leprcre/+; Rosa26tdTomato mouse with anti-LepR antibody. d Immunofluorescence staining of a 50-µm-thick bone marrow section using anti-LepR and anti-endomucin antibodies. Images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment. e Application of the anti-LepR antibody in human samples was demonstrated through staining of enzymatically dissociated human bone marrow cells. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with 3 human specimens. f Multilineage differentiation potential of CFU-F colonies formed by human LepR+ cells in panel (e). All Images are representative of 3 independent experiments with 3 human specimens

To verify the specificity of our anti-LepR monoclonal antibody, we used the Prx1-cre allele to conditionally delete Lepr in limb bone marrow stromal cells, excluding the axial skeleton. Flow cytometric analysis of femoral bone marrow from Prx1-cre; Leprfl/fl mice showed a significant reduction in LepR expression among PDGFRα+ stromal cells compared to controls (Fig. 7a, b). We then examined additional bone marrow compartments across various skeletal regions and observed significant LepR deletion in stromal cells from the pelvis, clavicle, sternum, scapula, humerus, radius, ulna, finger, fibula, and toe bone marrow (Fig. 7c). No deletion was detected in the calvaria, mandible, rib, or cervical and thoracic vertebrae. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) confirmed the reduction of Lepr transcripts in sorted stromal cells from the femoral bone marrow of Prx1-cre; Leprfl/fl mice (Fig. 7d). Immunofluorescence staining further demonstrated a predominant depletion of LepR expression in the femoral bone marrow (Fig. 7e, f), confirming the specificity of the monoclonal antibody.

Validation of the specificity of the anti-LepR monoclonal antibody in murine bone marrow and hypothalamus. a–c Flow cytometric analysis of bone marrow cells from 2-month-old mice demonstrates the specificity of the anti-LepR antibody in various skeletal sites. Data and images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment per genotype. a Most PDGFRα+ stromal cells in femur bone marrow were LepR+ from Leprfl/fl control mice but not from Prx1-cre; Leprfl/fl mice. b The anti-LepR monoclonal antibody labeled cells from Leprfl/fl control mice but not from Prx1-cre; Leprfl/fl mice. c The frequency of cells stained with the anti-LepR antibody in bone marrow from various skeletal sites was assessed, including the calvaria, mandible, rib, cervical and thoracic vertebrae, pelvis, clavicle, sternum, scapula, humerus, radius, ulna, fingers, fibula, and toe. d Lepr mRNA levels were determined by qRT-PCR in PDGFRα+ CD31−CD45−Ter119− femur bone marrow cells from Prx1-cre; Leprfl/fl and Leprfl/fl littermate control mice. Data are representative of 6 experiments with one mouse per experiment per genotype. e–h Representative staining of anti-LepR antibody in Leprfl/fl control mice (g) and Prx1-cre; Leprfl/fl mice (h) hypothalamus. Images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment per genotype

We generated a Lepr-mTagBFP2 (LeprmTagBFP2) knock-in reporter allele to facilitate the investigation of LepR+ cells, allowing for the specific visualization of these cells (Fig. S5a–c). By qRT-PCR, Lepr transcripts were enriched in flow cytometrically isolated bone marrow Lepr-mTagBFP2+ cells, but nearly undetectable in whole bone marrow cells or Lepr-mTagBFP2− cells (Fig. S5d). Immunofluorescence staining of the brain section revealed Lepr-mTagBFP2+ neurons in the hypothalamus (Fig. S5e), consistent with previous report using the LeprCre/+ allele.64 Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically dissociated bone marrow cells showed that (0.15 ± 0.06)% of bone marrow cells were Lepr-mTagBFP2+, with (98 ± 1.3)% co-expressing LepR (Fig. 8a). Deep imaging of bone hemisections confirmed that Lepr-mTagBFP2+ cells are predominantly perivascular, closely associated with endomucin+ vessels (Fig. 8b). This method ensures antibody penetration to a depth of at least 500 µm without significant reduction in signal intensity (Fig. S6a, b) or loss of antibody labeling specificity (Fig. S6c). The staining pattern of Lepr-mTagBFP2 in bone marrow sections overlapped with that of LepR antibody staining, corroborating the flow cytometric data (Fig. 8c). Furthermore, it is evident that bone marrow stromal cells, as indicated by Lepr-mTagBFP2 or Scf-GFP labeling, are not present on endosteal surfaces (Fig. S6b, c).

Characterization of a LeprmTagBFP2 reporter allele. a Flow cytometric analysis of enzymatically dissociated femur bone marrow cells from 2-month-old wild-type and LeprmTagBFP2/+ mice, demonstrating that most Lepr-mTagBFP2+ stromal cells were LepR+. 3 mice from 3 independent experiments. Deep imaging of femur bone hemisections from 2-month-old LeprmTagBFP2/+ mice shows that Lepr-mTagBFP2+ cells were perivascular, locating on endomucin+ vessels (b), and Lepr-mTagBFP2+ cells were all LepR+ (c). d Lepr-mTagBFP2+ cells are observed in the hypothalamus of LeprmTagBFP2/+ mice. Data and images are representative of 3 experiments with one mouse per experiment

Adaptations of the protocol for other experimental systems

Deep imaging has been extensively utilized by research groups to visualize the localization of diverse cell populations in various tissues. It has been particularly instrumental in examining how environmental and genetic factors influence cell distribution and proliferation in vivo.65,66,67,68,69,70 This protocol is not limited to bone marrow; it can be adapted to study other hematopoietic tissues, including the spleen.71 For instance, in the spleen, Vegfr3+ endothelial cells are predominantly found in the red pulp (Fig. 9a, b), and in ScfGFP/+ mice, Scf-GFP+ stromal cells are also mainly localized to the red pulp (Fig. 9c). Furthermore, this protocol allows for the visualization of PECAM1+ endothelial cells with detailed structural features in cleared lung tissue (Fig. 9d), consistent with previous findings.71,72 These applications demonstrate that the protocol is effective for soft tissues beyond the skeletal system and is likely applicable to a wide range of organs and tissues.

Deep imaging of the spleen and lung vasculature post optical clearing. a Deep imaging of the white pulp (WP) vasculature in a wild-type mouse spleen, visualized with antibodies against laminin (white) and endomucin (green). b Deep imaging of VEGFR3+ sinusoidal vessels in the red pulp (RP) of a wild-type mouse spleen. c Deep imaging of vasculature in the white pulp and red pulp of a spleen from a ScfGFP/+ mouse. d Deep imaging of endothelial cells and the basement membrane in the alveolus pulmonis of a wild-type mouse lung, using antibodies against laminin (green) and PECAM1 (red). Images are representative of three experiments with one mouse per experiment

Discussion

Optical clearing techniques, first introduced over a century ago by Spalteholz,73 have revolutionized volumetric imaging by overcoming the limitations imposed by light scatter in thick tissues. This method is crucial for organ-level imaging, where the working distance of the microscope and scattered light would otherwise hinder detailed visualization. In recent years, advanced optical imaging methods have been employed across various fields to study the three-dimensional architecture of cells within different organs.29,57,66,74,75,76,77 These studies have utilized fluorescence-based reporters through antibody labeling or transgenic mice, combined with various optical clearing approaches and imaging techniques such as confocal or two-photon microscopy. The successful implementation of a high-resolution deep imaging method requires the development of a customized antibody labeling and optical clearing pipeline tailored to the tissue of interest that is time- and cost-effective as well as providing acceptable results.

In the past decade, advancements in optical clearing techniques have enabled the immunofluorescence staining of opaque tissues, with iDISCO,38,66,70,74,78 PEGASOS,77,79,80 and other examples.57,81 A comparison of these methods is detailed in Table 4. The assay we present offers the benefits of a shorter processing time, approximately 11 to 12 days, and is more cost-effective for high-resolution immunofluorescence staining and imaging. However, it is not without limitations. Unlike traditional bone section staining, our method permits only one staining combination per bone sample. Additionally, certain chemical stains, including Oil Red O,82 are incompatible with our protocol due to the delipidization phase. Compatibility of antibody and fluorophore combinations must be verified, as with iDISCO and other clearing techniques, to ensure they withstand the fixation, permeabilization, and clearing processes. Despite these considerations, the costs associated with deep imaging through optical clearing remain higher than those of traditional section staining methods.

Our optimized imaging methods are designed for efficiency and can be applied across a spectrum of organs, regardless of age. These techniques enable us to elucidate the intricate architecture and cellular components of tissues, and crucially, to analyze the spatial relationships among various cellular elements. This includes the ability to examine transcortical vessels and other cellular interactions both quantitatively and qualitatively. The ongoing evolution of optical clearing techniques and volumetric imaging, particularly when combined with diverse antibody labeling, is set to significantly improve our understanding of rare cell populations and their spatial dynamics within organs. This advancement is expected to provide deeper insights into tissue behavior under homeostatic, regenerative, and pathological states.

Materials and methods

Mice

All mouse experiments complied with all relevant ethical regulations and were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing. All mice were maintained on a C57BL/6 J background, including Leprcre (JAX: 00832064), Prx1-cre (JAX: 005584), Leprflox (JAX: 008327), Rosa26tdTomato (Ai14) (JAX: 00791483), Rosa26TriGFP (Ai4784), Col1a1*2.3-eGFP (JAX: 01313485), OlnmTomato (ref. 4), NgfmScarlet (JAX: 0394329), and ScfGFP (JAX: 0178601).

To generate LeprmTagBFP2 mice, Cas9 mRNA, single guide RNA, and targeting vector containing 3 × mTagBFP2 inserted before stop codon of the Lepr gene were co-microinjected into C57BL/6 J zygotes. The coding sequence for the monomeric blue fluorescent protein (mTagBFP2) was as described.86 Chimeric mice were genotyped by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis and insertion of the 3 × mTagBFP2 sequence into the correct locus was confirmed by Southern blotting and sequencing of the targeted allele. Founders were mated with C57BL/6 J mice to obtain germline transmission then backcrossed with wild-type C57BL/6 J mice for at least three generations before analysis. Genotyping primers for genotyping LeprmTagBFP2 mice were Lepr-Com-G2, 5ʹ-CTT TCT CTA GCA GCT CCT GGG AG-3ʹ; Lepr-mTagBFP2-G3, 5ʹ-CAG TAG ACT AAA ATT CGT CGC TC-3ʹ; and Lepr-WT-G1, 5ʹ-GAG ACC TTC CCC AAG TAT CTT GG-3ʹ.

Bone hemisection and thick section preparations

Mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation. Intact mouse femurs and tibias were carefully dissected by removing all surrounding tissues without causing any damage to the bones. The bones were then transferred to 15-mL centrifuge tubes filled with ice-cold (i.e., placed on ice for ~15 min) 4% PFA (Solarbio, P1110) and were incubated at 4 °C on a rotator for 6 h. After fixation, the bone samples were washed twice with PBS (at least 10 mL PBS per wash) under constant agitation in a 15-mL centrifuge tube at 4 °C. The bone samples were then incubated with 15 mL ice-cold EDTA (0.5 mol/L, dissolved in water at pH 8.0; Solarbio, E8040) for decalcification (this step can be optional). The bones were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with 10 mL ice-cold 30% sucrose (Macklin, S818046) solution under constant agitation on a rotator at 4 °C for 12 h, followed by OCT (Sakura, 4583) embedding.

The embedded long bones were sectioned longitudinally at a thickness of 50–100 µm using a new precooled, low-profile microtome blade until the sinus and the full longitude of the long bone were fully exposed, to generate the bone hemisections (over 500 µm in thickness from adult mice at 2–4 months of age). For experiments using bone sections, OCT-embedded femurs were sectioned using the CryoJane tape-transfer system (Leica Biosystems). Sections were blocked in PBS with 5% donkey serum (Jackson Immuno, 017-000-121) for 1 h and then stained with primary antibodies overnight.

Flow cytometry and in vitro differentiation assay

For flow cytometric analysis, bone marrow cells from mice were flushed using Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Beyotime, C0218) with 2% bovine serum (Gemini, 900-108) and then enzymatically dissociated as described.31 Anti-LepR (Abcam, ab318272), anti-CD45 (30F-11, Invitrogen, 11-0451-85), anti-CD31 (390, Invitrogen, 11-0311-85), and anti-TER119 (TER119, BioLegend, 116206) were used to isolate LepR+ stromal cells that were negative for hematopoietic and endothelial markers. Anti-PDGFRα-biotin (eBioscience, clone APA5, 1:200), anti-CD45 (30F-11, Invitrogen, 11-0451-85), anti-CD31 (390, Invitrogen, 11-0311-85), and anti-TER119 (TER119, BioLegend, 116206) were used to isolate PDGFRα+ stromal cells that were negative for hematopoietic and endothelial markers. For the analysis of human bone marrow, samples were isolated from patients undergoing hip arthroplasty, and LepR+ stromal cells were isolated using anti-LepR (Abcam, ab318272), CD31 (WM59, BioLegend, 303104), CD45 (2D1, BioLengend, 368508), CD45R (RA3-6B2, BioLegend, 103206), CD41 (HIP8, BioLegend, 303704), CD61 (VI-PL2, BioLegend, 336404), CD71 (MEM-75, Abcam, AB239251), and CD235ab (HIR2, BioLegend, 306610).

All human studies were conducted in accordance with the official ethical guidelines and protocols approved by the Ethics Committee of the Peking University People’s Hospital (2024-z063). For analysis of human bone marrow cells, fresh bone marrow was drawn from the proximal femur of patients who underwent total hip replacement in Peking University People’s Hospital. We collected discarded bone marrow during femoral medullary reaming in total hip replacement. CFU-F assays were performed similarly as described previously for mouse bone marrow stromal cells,31 followed by osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation with StemPro Differentiation Kits (Invitrogen, A1007201 for osteogenic differentiation; Invitrogen, A1007001 for adipogenic differentiation). Osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation were assessed using Alizarin Red S (OriCell, OILR-10001), and Oil Red O staining (Sigma-Aldrich, O0625).

Immunofluorescence staining

The bone hemisections were transferred to 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tubes, placed on ice, and washed twice with 1.5 mL of PBS to remove the OCT completely. The PBS solution was removed, and the hemisections were incubated with 5% donkey serum in 0.5% PBST for 6 h at room temperature with shaking to reduce non-specific background signal. After that, the hemisections were transferred to a new 0.6-mL centrifuge tube using forceps, and 550 μL of primary antibody staining solution (blocking solution with primary antibody cocktail) was added. The hemisections were then incubated with shaking at room temperature for 3 days. After the primary antibody incubation, the hemisections were transferred to a new 1.5-mL centrifuge tube with forceps and were washed three times with PBS for 15 min each at room temperature. A fourth wash with PBS was carried out overnight with shaking at room temperature. The washed hemisections were then transferred to a new 0.6-mL centrifuge tube using forceps, and 550 μL of secondary antibody solution (blocking solution with secondary antibody cocktail) was added. The hemisections were then incubated with shaking at room temperature in the dark for 3 days, followed by another three washes as described above in a 1.5-mL microcentrifuge tube. For bone sections, primary antibodies were stained overnight, followed by three washes for 20 min each, and secondary antibodies were incubated for 1 h, followed by three washes for 20 min each.

Optical clearing of stained tissues

At least 24 h before the optical clearing steps, the BABB buffer needs to be prepared. A 50-mL BABB mixture [benzyl alcohol (Macklin, B802546) /benzyl benzoate (Aladdin, B400547) = 1:2 (vol/vol)] is prepared in a glass cylinder and then is added to a 50-mL centrifuge tube containing 5 g of aluminum oxide (Macklin, A800193). The centrifuge tube is sealed with Parafilm and wrapped with aluminum foil to block out any light. The mixture is incubated with shaking for (24–48)h. Before the BABB is used for optical clearing, the mixture is centrifuged at 800 × g for 15 min at room temperature.

The hemisections are then dehydrated by methanol incubation for 5 min and repeated three times, with 1.5 mL of methanol for each wash. After dehydration, the hemisections are cleared with one or two washes with BABB. The hemisections are incubated in BABB with shaking at room temperature in the dark for several hours to overnight. The BABB is then replaced with fresh BABB, and the filled microcentrifuge tube is wrapped in aluminum foil. The hemisections can be stored at 4 °C in BABB in the dark for up to at least 3 months before imaging.

Preparing mounting slide for image acquisition

After optical clearing, the hemisection sample in BABB is mounted within the custom quartz mold. The design of this mounting system is shown in Fig. S1. Silicone gel (Soudal, Silirub 2/S) was drawn up into a 10-mL syringe and carefully squeezed out into the mold. The hemisection sample was placed on top of the fresh silicone. Importantly, the sample was oriented with the marrow cavity facing up and was adjusted to be as close to horizontal (i.e., parallel to the bottom of the dish) as possible. A few drops of BABB were added to the silicone pad, and the silicone foundation was allowed to solidify at room temperature for 30 min before the pool was filled with fresh BABB to immerse the hemisection sample. The mounted section was then used for image acquisition. Note that the stained and cleared bone hemisections can be preserved for up to at least 3 months without any notable loss of fluorescence, if they are stored in BABB at 4 °C in the dark.

Data acquisition and analysis

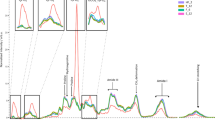

Bone hemisection samples are thick (>500 µm), which can lead to substantial background fluorescence. To image the skeletal architecture in three dimensions at high resolution with minimal background signal, we used a Leica Stellaris or Leica SP8 resonant confocal laser-scanning microscope with z-stack scanning and tiling to obtain sequential depth images. Laser lines used were at 488, 561, and 633 nm. The Leica confocal microscope allowed us to image multiple channels efficiently and minimized the acquisition time. We used an 8-kHz resonant tandem scanner with both HyD (hybrid detector) and PMT (photomultiplier tube) detectors and used 3× line averaging to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio. Deep imaging of the stained tissue requires a long working distance objective, with a refractive index (1.56) matching the optimum for the clearing agent BABB. We chose the HCX APO L20×/0.95 BABB immersion objective with a 1.95-mm working distance to achieve deep imaging of thick tissues in the presence of BABB. Pixel size was set as 0.867 × 0.867 µm, pinhole size was 46.9 µm, and each z-step was 2 µm. The Alexa 488 channel can sometimes result in a high background fluorescence after tissue clearing. Optimal acquisition settings and antibody combinations were chosen to balance the imaging time and imaging quality (adequate lateral and axial resolution, high signal-to-noise ratio for further quantification and analysis). For tissues such as muscle that have a high background signal, multispectral imaging can be used to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.87

After image acquisition, the tiled z-stack images were converted into “.ims” or “.aivia.tif” format using Imaris x64 10.1.0 (Bitplane) or Aivia 12.1.0 respectively, followed by three-dimensional rendering, snapshot generation, and quantification. Aivia 12.1.0 or Bitplane Imaris x64 10.1.0 was installed on a ThinkStation P920 Workstation with Dual Intel Xeon Platinum 8160 T CPU @ 2.10 GHz, 1.00 TB RAM, and an NVIDIA Quadro RTX 8000 graphics card. We first set the blood vessels or bone as different surfaces based on the antibody staining or SHG signal using the surface function of Imaris. Based on Laminin antibody staining and morphological differences, arteries and sinusoids were manually labeled and further applied to the machine-learning process with the ‘Machine Learning Segmentation’ with ‘All Channels’ function in Imaris to identify arteries and sinusoids in the samples. As previously described,29 the outer 20% of the bone marrow by volume was set as transition zone (TZ). The bone marrow cavity and TZ vessel surface were labeled every 5-10 slices. Next, we saved the current surface with Export Scene function and load the original ‘.ims’ file for further analysis. The ortho slicer function in Imaris was then used to identify individual α-catulin-GFP+c-kit+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) across the slices in the large three-dimensional images. The HSCs were determined based on a round morphology and a co-expression of GFP and c-kit. The spot function in Imaris was then applied to set these identified HSCs as spots, with “object-object statistics” in the algorithm setting options selected with default parameters. We created a randomly located spot assembly by using a Matlab script, in which we could set the same number of spots of 6μm diameter and spread them in the exact same volume of the crop which we analyzed the number of HSCs. We then created a Spot subject in the Imaris file which represented the randomly spread spots using Matlab. After all these, we imported all the surfaces and spots into the original Imaris file and entered the ‘Vantage’ interface. Finally, we exported the distance of every single spot to the different surfaces in ‘details’, compared the differences, and calculated the percentages with the object-object statistics.

References

Ding, L., Saunders, T. L., Enikolopov, G. & Morrison, S. J. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 481, 457–462 (2012).

Himburg, H. A. et al. Distinct bone marrow sources of pleiotrophin control hematopoietic stem cell maintenance and regeneration. Cell Stem cell 23, 370–381.e375 (2018).

Ding, L. & Morrison, S. J. Haematopoietic stem cells and early lymphoid progenitors occupy distinct bone marrow niches. Nature 495, 231–235 (2013).

Shen, B. et al. A mechanosensitive peri-arteriolar niche for osteogenesis and lymphopoiesis. Nature 591, 438–444 (2021).

Emoto, T. et al. Colony stimulating factor-1 producing endothelial cells and mesenchymal stromal cells maintain monocytes within a perivascular bone marrow niche. Immunity 55, 862–878 e868 (2022).

Zhong, L. et al. Csf1 from marrow adipogenic precursors is required for osteoclast formation and hematopoiesis in bone. eLife 12, e82112 (2023).

Greenbaum, A. et al. CXCL12 in early mesenchymal progenitors is required for haematopoietic stem-cell maintenance. Nature 495, 227–230 (2013).

Wu, L. et al. LepR+ niche cell-derived AREG compromises hematopoietic stem cell maintenance under conditions of DNA repair deficiency and aging. Blood 142, 1529–1542 (2023).

Gao, X. et al. Leptin receptor(+) cells promote bone marrow innervation and regeneration by synthesizing nerve growth factor. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 1746–1757 (2023).

Meacham, C. E. et al. Adiponectin receptors sustain haematopoietic stem cells throughout adulthood by protecting them from inflammation. Nat. Cell Biol. 24, 697–707 (2022).

Zhou, B. O., Yue, R., Murphy, M. M., Peyer, J. G. & Morrison, S. J. Leptin-receptor-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells represent the main source of bone formed by adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 15, 154–168 (2014).

Shu, H. S. et al. Tracing the skeletal progenitor transition during postnatal bone formation. Cell Stem Cell 28, 2122–2136.e2123 (2021).

Jeffery, E. C., Mann, T. L. A., Pool, J. A., Zhao, Z. & Morrison, S. J. Bone marrow and periosteal skeletal stem/progenitor cells make distinct contributions to bone maintenance and repair. Cell Stem Cell 29, 1547–1561.e1546 (2022).

Baccin, C. et al. Combined single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal the molecular, cellular and spatial bone marrow niche organization. Nat. Cell Biol. 22, 38–48 (2020).

Baryawno, N. et al. A cellular taxonomy of the bone marrow stroma in homeostasis and leukemia. Cell 177, 1915–1932.e1916 (2019).

Fang, S. et al. VEGF-C protects the integrity of the bone marrow perivascular niche in mice. Blood 136, 1871–1883 (2020).

Tikhonova, A. N. et al. The bone marrow microenvironment at single-cell resolution. Nature 569, 222–228 (2019).

Wolock, S. L. et al. Mapping distinct bone marrow niche populations and their differentiation paths. Cell Rep. 28, 302–311.e305 (2019).

Matsushita, Y. et al. A Wnt-mediated transformation of the bone marrow stromal cell identity orchestrates skeletal regeneration. Nat. Commun. 11, 332 (2020).

Zhong, L. et al. Single cell transcriptomics identifies a unique adipose lineage cell population that regulates bone marrow environment. eLife 9, e54695 (2020).

Zhou, B. O. et al. Bone marrow adipocytes promote the regeneration of stem cells and haematopoiesis by secreting SCF. Nat. Cell Biol. 19, 891–903 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Gli1 identifies osteogenic progenitors for bone formation and fracture repair. Nat. Commun. 8, 2043 (2017).

Mo, C. et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of LepR-positive skeletal cells reveals heterogeneous stress-dependent stem and progenitor pools. EMBO J. 41, e108415 (2022).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Mapping the cellular biogeography of human bone marrow niches using single-cell transcriptomics and proteomic imaging. Cell 187, 3120–3140.e3129 (2024).

Comazzetto, S., Shen, B. & Morrison, S. J. Niches that regulate stem cells and hematopoiesis in adult bone marrow. Dev. Cell 56, 1848–1860 (2021).

Morrison, S. J. & Scadden, D. T. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 505, 327–334 (2014).

Zhang, J. et al. In situ mapping identifies distinct vascular niches for myelopoiesis. Nature 590, 457–462 (2021).

Wu, Q. et al. Resilient anatomy and local plasticity of naive and stress haematopoiesis. Nature 627, 839–846 (2024).

Acar, M. et al. Deep imaging of bone marrow shows non-dividing stem cells are mainly perisinusoidal. Nature 526, 126–130 (2015).

Yue, R., Shen, B. & Morrison, S. J. Clec11a/osteolectin is an osteogenic growth factor that promotes the maintenance of the adult skeleton. eLife 5, e18782 (2016).

Shen, B. et al. Integrin alpha11 is an Osteolectin receptor and is required for the maintenance of adult skeletal bone mass. eLife 8, e42274 (2019).

Zhang, J. et al. The effect of parathyroid hormone on osteogenesis is mediated partly by osteolectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2026176118 (2021).

Zhang, J. et al. Bone marrow dendritic cells regulate hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell trafficking. J. Clin. Invest 129, 2920–2931 (2019).

Zhao, Y. C. et al. A novel computational biomechanics framework to model vascular mechanopropagation in deep bone marrow. Adv. Health. Mater. 12, e2201830 (2023).

Chen, J. Y. et al. Hoxb5 marks long-term haematopoietic stem cells and reveals a homogenous perivascular niche. Nature 530, 223–227 (2016).

Kokkaliaris, K. D. et al. Adult blood stem cell localization reflects the abundance of reported bone marrow niche cell types and their combinations. Blood 136, 2296–2307 (2020).

Christodoulou, C. et al. Live-animal imaging of native haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nature 578, 278–283 (2020).

Jacob, L. et al. Anatomy and function of the vertebral column lymphatic network in mice. Nat. Commun. 10, 4594 (2019).

Kiel, M. J. et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell 121 1109–1121 (2005).

Zhu, J. et al. Osteoblasts support B-lymphocyte commitment and differentiation from hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 109, 3706–3712 (2007).

Wu, J. Y. et al. Osteoblastic regulation of B lymphopoiesis is mediated by Gsalpha-dependent signaling pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 16976–16981 (2008).

Katayama, Y. et al. Signals from the sympathetic nervous system regulate hematopoietic stem cell egress from bone marrow. Cell 124, 407–421 (2006).

Zhang, S. et al. Bone marrow adipocytes fuel emergency hematopoiesis after myocardial infarction. Nat. Cardiovasc Res. 2, 1277–1290 (2023).

Maryanovich, M. et al. Adrenergic nerve degeneration in bone marrow drives aging of the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Nat. Med. 24, 782–791 (2018).

Fielding, C. et al. Cholinergic signals preserve haematopoietic stem cell quiescence during regenerative haematopoiesis. Nat. Commun. 13, 543, (2022).

Gadomski, S. et al. A cholinergic neuroskeletal interface promotes bone formation during postnatal growth and exercise. Cell Stem Cell 29, 528–544 (2022).

Gao, X. et al. Nociceptive nerves regulate haematopoietic stem cell mobilization. Nature 589, 591–596 (2020).

Sarkaria, S. M. et al. Systematic dissection of coordinated stromal remodeling identifies Sox10(+) glial cells as a therapeutic target in myelofibrosis. Cell Stem Cell 30, 832–850.e836 (2023).

Yamazaki, S. et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell 147, 1146–1158 (2011).

Lucas, D. et al. Chemotherapy-induced bone marrow nerve injury impairs hematopoietic regeneration. Nat. Med. 19, 695–703 (2013).

Fukuda, T. et al. Sema3A regulates bone-mass accrual through sensory innervations. Nature 497, 490–493 (2013).

Mahmoud, A. I. et al. Nerves regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration. Dev. Cell 34, 387–399 (2015).

Ambrosi, T. H. et al. Aged skeletal stem cells generate an inflammatory degenerative niche. Nature 597, 256–262 (2021).

Young, K. A. et al. Variation in mesenchymal KITL/SCF and IGF1 expression in middle age underlies steady-state hematopoietic stem cell aging. Blood 144, 378–391 (2024).

Mitchell, C. A. et al. Stromal niche inflammation mediated by IL-1 signalling is a targetable driver of haematopoietic ageing. Nat. Cell Biol. 25, 30–41 (2023).

Allocca, G., Kusumbe, A. P., Ramasamy, S. K. & Wang, N. Confocal/two-photon microscopy in studying colonisation of cancer cells in bone using xenograft mouse models. Bonekey Rep. 5, 851 (2016).

Chen, J. et al. High-resolution 3D imaging uncovers organ-specific vascular control of tissue aging. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd7819 (2021).

Kusumbe, A. P., Ramasamy, S. K. & Adams, R. H. Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature 507, 323–328 (2014).

Kusumbe, A. P. et al. Age-dependent modulation of vascular niches for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 532, 380–384 (2016).

Ramasamy, S. K., Kusumbe, A. P., Wang, L. & Adams, R. H. Endothelial Notch activity promotes angiogenesis and osteogenesis in bone. Nature 507, 376–380 (2014).

Gruneboom, A. et al. A network of trans-cortical capillaries as mainstay for blood circulation in long bones. Nat. Metab. 1, 236–250 (2019).

He, J. et al. Dissecting human embryonic skeletal stem cell ontogeny by single-cell transcriptomic and functional analyses. Cell Res 31, 742–757 (2021).

Chan, C. K. F. et al. Identification of the human skeletal stem cell. Cell 175, 43–56.e21 (2018).

DeFalco, J. et al. Virus-assisted mapping of neural inputs to a feeding center in the hypothalamus. Science 291, 2608–2613 (2001).

Merz, S. F. et al. Contemporaneous 3D characterization of acute and chronic myocardial I/R injury and response. Nat. Commun. 10, 2312 (2019).

Renier, N. et al. iDISCO: a simple, rapid method to immunolabel large tissue samples for volume imaging. Cell 159, 896–910 (2014).

Richardson, D. S. & Lichtman, J. W. Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell 162, 246–257 (2015).

Tomer, R., Ye, L., Hsueh, B. & Deisseroth, K. Advanced CLARITY for rapid and high-resolution imaging of intact tissues. Nat. Protoc. 9, 1682–1697 (2014).

Yang, B. et al. Single-cell phenotyping within transparent intact tissue through whole-body clearing. Cell 158, 945–958 (2014).

Yao, Y., Taub, A. B., LeSauter, J. & Silver, R. Identification of the suprachiasmatic nucleus venous portal system in the mammalian brain. Nat. Commun. 12, 5643 (2021).

Inra, C. N. et al. A perisinusoidal niche for extramedullary haematopoiesis in the spleen. Nature 527, 466–471 (2015).

Poulos, M. G. et al. Complementary and inducible creER(T2) mouse models for functional evaluation of endothelial cell subtypes in the bone marrow. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 20, 1135–1149 (2024).

Spalteholz, W. Uber das durchsichtigmachen von menschlichen und tierischen praparaten [About the transparency of human and animal preparations]. (1914).

Pan, C. et al. Shrinkage-mediated imaging of entire organs and organisms using uDISCO. Nat. Methods 13, 859–867 (2016).

Greenbaum, A. et al. Bone CLARITY: clearing, imaging, and computational analysis of osteoprogenitors within intact bone marrow. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaah6518 (2017).

Dodt, H. U. et al. Ultramicroscopy: three-dimensional visualization of neuronal networks in the whole mouse brain. Nat. Methods 4, 331–336 (2007).

Jing, D. et al. Tissue clearing of both hard and soft tissue organs with the PEGASOS method. Cell Res. 28, 803–818 (2018).

Li, Y., Xu, J., Wan, P., Yu, T. & Zhu, D. Optimization of GFP fluorescence preservation by a modified uDISCO clearing protocol. Front Neuroanat. 12, 67 (2018).

Yi, Y. et al. 3-dimensional visualization of implant-tissue interface with the polyethylene glycol associated solvent system tissue clearing method. Cell Prolif. 52, e12578 (2019).

Yi, Y. et al. Mapping of individual sensory nerve axons from digits to spinal cord with the transparent embedding solvent system. Cell Res 34, 124–139 (2024).

Wang, Q., Liu, K., Yang, L., Wang, H. & Yang, J. BoneClear: whole-tissue immunolabeling of the intact mouse bones for 3D imaging of neural anatomy and pathology. Cell Res 29, 870–872 (2019).

Dazzi, M., Rowland, E. M., Mohri, Z. & Weinberg, P. D. 3D confocal microscope imaging of macromolecule uptake in the intact brachiocephalic artery. Atherosclerosis 310, 93–101 (2020).

Madisen, L. et al. A robust and high-throughput Cre reporting and characterization system for the whole mouse brain. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133–140 (2010).

Daigle, T. L. et al. A suite of transgenic driver and reporter mouse lines with enhanced brain-cell-type targeting and functionality. Cell 174, 465–480.e422 (2018).

Kalajzic, Z. et al. Directing the expression of a green fluorescent protein transgene in differentiated osteoblasts: Comparison between rat type I collagen and rat osteocalcin promoters. Bone 31, 654–660 (2002).

Subach, O. M., Cranfill, P. J., Davidson, M. W. & Verkhusha, V. V. An enhanced monomeric blue fluorescent protein with the high chemical stability of the chromophore. PloS one 6, e28674 (2011).

Mansfield, J. R., Gossage, K. W., Hoyt, C. C. & Levenson, R. M. Autofluorescence removal, multiplexing, and automated analysis methods for in-vivo fluorescence imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 10, 41207 (2005).

Foster, D. S. et al. A clearing technique to enhance endogenous fluorophores in skin and soft tissue. Sci. Rep. 9, 15791 (2019).

Klingberg, A. et al. Fully automated evaluation of total glomerular number and capillary tuft size in nephritic kidneys using lightsheet microscopy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 452–459 (2017).

Masselink, W. et al. Broad applicability of a streamlined ethyl cinnamate-based clearing procedure. Development 146, dev.166884 (2019).

Si, Y. et al. Multidimensional imaging provides evidence for down-regulation of T cell effector function by MDSC in human cancer tissue. Sci. Immunol. 4, eaaw9159 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was mainly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82272563 to B.S.), the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant number 2023ZD0501202 to B.S.), and institutional grants allocated to the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing (NIBS) from the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology, Beijing Municipal Commission of Science and Technology, and Tsinghua University. Additionally, we acknowledge the support from China Pharmaceutical University (grant number 3150140001 to S.F.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 82203653 to S.F., 82371957 to L.W., and 82371956 to X.C.), the Beijing Municipal Public Welfare Development and Reform Pilot Project for Medical Research Institutes (grant number JYY2023-8 to X.C.), and the Research Grants Council of University Grants Committee Hong Kong (grant numbers 14113723, 14108720, 14121721, 14202920, N_CUHK472/22, C7030-18G, T13-402/17-N, and AoE/M-402/20). We gratefully acknowledge the generous support from these funding agencies. Furthermore, we extend our gratitude to Hongkui Zeng from the Allen Institute for providing us with the Rosa26TriGFP (Ai47) allele.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.N. performed most of the experiments, with assistance from J. W. and F.L., Y.Yi, X.G., L.X., W.Z., Z.C., and P.C. J.W. screened out the anti-LepR antibody clone in collaboration with Abcam, with assistance from X.M. D.X. and Y.Yuan provided the human bone marrow samples. D.D., G.S., M.Y., R.W, L.W., L.M.N.M., J.M.U., and A.T. assisted with experiments and/or participated in discussions during the writing of the manuscript. S.L., X.C., and G.L. advised on the experiment design and manuscript. Y.N., S.F., and B.S. designed the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript with assistance from H.Z., J.M.U., and A.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ni, Y., Wu, J., Liu, F. et al. Deep imaging of LepR+ stromal cells in optically cleared murine bone hemisections. Bone Res 13, 6 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-024-00387-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41413-024-00387-9