Abstract

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists (GLP-1RAs) ameliorate mitochondrial health by increasing mitochondrial turnover in metabolically relevant tissues. Mitochondrial adaptation to metabolic stress is crucial to maintain pancreatic β-cell function and prevent type 2 diabetes (T2D) progression. While the GLP-1R is well-known to stimulate cAMP production leading to Protein Kinase A (PKA) and Exchange Protein Activated by cyclic AMP 2 (Epac2) activation, there is a lack of understanding of the molecular mechanisms linking GLP-1R signalling with mitochondrial and β-cell functional adaptation. Here, we present a comprehensive study in β-cell lines and primary islets that demonstrates that, following GLP-1RA stimulation, GLP-1R-positive endosomes associate with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane contact site (MCS) tether VAPB at ER-mitochondria MCSs (ERMCSs), where active GLP-1R engages with SPHKAP, an A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) previously linked to T2D and adiposity risk in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). The inter-organelle complex formed by endosomal GLP-1R, ER VAPB and SPHKAP triggers a pool of ERMCS-localised cAMP/PKA signalling via the formation of a PKA-RIα biomolecular condensate which leads to changes in mitochondrial contact site and cristae organising system (MICOS) complex phosphorylation, mitochondrial remodelling, and β-cell functional adaptation, with important consequences for the regulation of β-cell insulin secretion and survival to stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maintenance of mitochondrial function and adaptation to changes in nutritional state is vital for the preservation of pancreatic β-cell regulated secretion of insulin1, the main hormone in charge of lowering blood glucose concentrations, with disruptions in this process underlying the development and/or progression of type 2 diabetes (T2D)1,2—an uncontrolled pandemic affecting ∼500 million people worldwide, and causing ∼1.5 million deaths per year3. The incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), released from the gut during food intake, amplifies glucose-stimulated insulin release by binding to and activating its cognate G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R), triggering cAMP generation and downstream Protein Kinase A (PKA) and Exchange Protein Activated by cyclic AMP 2 (Epac2) signalling4, a process that has been exploited to develop pharmacological GLP-1R agonists (GLP-1RAs) as T2D therapies. There is extensive data highlighting the beneficial role of GLP-1RAs in the maintenance and/or restoration of mitochondrial function in β-cells and beyond, with reports emphasising their capacity to induce mitochondrial remodelling/turnover and functional adaptation5,6,7,8, two closely intertwined processes essential for the preservation of optimal metabolic activity9. While a range of GLP-1R-induced pathways have been suggested, there is no clear description of the molecular mechanism engaged by the receptor to modulate mitochondrial remodelling and improve mitochondrial function. Here, we present evidence in β-cells and primary mouse and human islets which demonstrates that, following agonist binding and internalisation, endosomal GLP-1R binds to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localised ER-mitochondria membrane contact site (ERMCS) organising factor VAPB to engage SPHKAP, a PKA-RIα-specific A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) whose gene coding variants have previously been linked to T2D and high BMI risk in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). We further show that SPHKAP itself localises to ERMCSs via its direct interaction with VAPB through a pFFAT motif present in SPHKAP. Establishment of a membrane contact site (MCS) between endosomal GLP-1R, ERMCS-localised VAPB and SPHKAP leads to the generation of a highly-localised cAMP/PKA signalling hub that triggers the PKA-dependent phosphorylation of the mitochondrial contact site and cristae organising system (MICOS) complex, mitochondrial remodelling, and improved mitochondrial function, leading to potentiation of insulin secretion and survival to ER stress downstream of GLP-1R action. This is, to our knowledge, the first description of a three-way contact between an endosomal GPCR, the ERMCS tether VAPB, and a PKA-RIα-recruiting AKAP, which uncovers the assembly of a GLP-1R-induced ERMCS-localised PKA biomolecular condensate to control mitochondrial turnover and function. Our data not only unveils a previously unknown pathway of ERMCS-localised GPCR signalling into mitochondria, potentially applicable to other GPCRs beyond the GLP-1R, but also opens the door to further roles of the GLP-1R in the regulation of mitochondrial lipid metabolism, a process tightly linked to changes in mitochondrial morphology governed by MICOS complex activity10. In summary, this study has uncovered the molecular mechanism employed by the GLP-1R to achieve mitochondrial regeneration leading to optimised β-cell function, with important repercussions for our understanding of the role of GLP-1RAs in disorders such as T2D, obesity, and neurodegeneration.

Results

Human GLP-1R β-cell interactome reveals binding of agonist-stimulated GLP-1R to signalling effectors, with strong prevalence of ERMCS-localised proteins

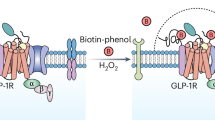

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the specific downstream partners and signalling mediators engaged by active GLP-1Rs in pancreatic β-cells, we performed an interactome analysis of proteins that bind to the receptor under vehicle versus 5-minute stimulation with the GLP-1RA exendin-4 in a subline of rat INS-1 832/3 β-cells stably expressing SNAP/FLAG-tagged human GLP-1R (SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R). Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis of GLP-1R co-immunoprecipitants revealed a list of proteins enriched in agonist-stimulated versus unstimulated conditions (Fig. 1a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Gene ontology analysis of the identified factors indicated that these were involved in pathways related to endomembranes and the ER (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Amongst these factors, we found a high number of proteins localised to ERMCSs (Fig. 1c), which are points of close interaction, but not fusion, between the ER and mitochondria that fulfil specific functions including cross-organelle ion and lipid sensing and transfer, and signal transmission to coordinate mitochondrial remodelling11. While known GLP-1R interactors such as GαS, AP2, Rab5, and β-arrestin 2 were reassuringly identified in our interactomics list, the most prominently enriched factor interacting with active GLP-1R was VAMP Associated Protein B (VAPB), followed by its homologue VAPA, integral ER proteins whose main role is the establishment and maintenance of organelle-ER interactions, or MCSs12,13, including those involving endosomes and/or mitochondria. We next validated the active GLP-1R binding to VAPB inferred from our MS results by co-immunoprecipitating both EGFP-VAPB (Fig. 1d) and endogenous VAPB (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1c) with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in vehicle versus exendin-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells. Confocal microscopy analysis of vehicle versus exendin-4-stimulated SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R co-localisation with EGFP-VAPB in these cells revealed that, upon exendin-4 stimulation, the GLP-1R traffics from the plasma membrane to endosomes intimately associated with VAPB-positive ER regions (Supplementary Fig. 1d,e), with the ER often surrounding a central core of GLP-1R-positive signal (Fig. 1f), suggesting that GLP-1R-containing endosomes directly contact VAPB-positive ER membranes, likely via MCSs. This hypothesis was validated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) localisation of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (labelled at the cell surface with SNAP-biotin plus streptavidin-gold particles in living cells prior to exendin-4 stimulation) to endosome-ER MCSs (Fig. 1g). Further microscopy experiments performed to visualise GLP-1R engagement with EGFP-VAPB in response to exendin-4 stimulation include confocal imaging of serial optical sections covering the entire cell thickness after SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R surface labelling with a membrane impermeable SNAP-tag probe followed by exendin-4 stimulation, represented as a maximum intensity projection (MIP) in Fig. 1h, and time-lapse confocal microscopy analysis of exendin-4-induced SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R trafficking from the plasma membrane to endosomes in close proximity to EGFP-VAPB-positive ER regions (Supplementary Fig. 1f and Supplementary Movie 1). Two-colour nanometre-scale resolution imaging by Minimal Photon Fluxes (MINFLUX), an ultra-high resolution microscopy technique that combines aspects of single-molecule localisation microscopy and stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy14, was employed to determine the average distance between endosomal SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R and VAPB, estimated at around 28 nm (Fig. 1i, j), compatible with the expected distance of an ER-endosome MCS15.

a Heatmap of GLP-1R interactor enrichment from anti-FLAG co-immunoprecipitates of vehicle (Veh) versus 5-minute exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells; blue, decreased; red, increased binding; LC-MS/MS data analysed in LFQ-Analyst and normalised to hGLP-1R levels for each experimental repeat; colour scale centred around overall median value of the experiment; n = 4 biologically independent experiments. b Volcano plot of data from (a) depicting log2 fold change to vehicle (x-axis) versus -log10qvalue (y-axis). c List of ER, mitochondria or ERMCS-localised hGLP-1R interactors enriched in exendin-4-stimulated versus vehicle conditions. d Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of EGFP-VAPB with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells. Representative blots and quantification of EGFP-VAPB over SNAP levels shown; n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. e As for (d) for endogenous VAPB; n = 4 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. f Confocal microscopy analysis of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (red) co-localisation with EGFP-VAPB (green) in Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells; box, magnification inset; size bar, 5 μm; image representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. g Electron microscopy micrograph depicting gold-labeled SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (arrows) localised to an endosome–ER MCS in an Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cell; endosome highlighted in gold and ER in blue; size bar, 100 nm; image representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. h Maximum intensity projection (MIP) of a confocal z-stack of EGFP-VAPB (green) and SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (red) from an Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cell; size bar, 10 μm; image representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. i Confocal detection of FLUX 680-labelled VAPB (magenta) and SNAP-Surface Alexa Fluor 647-labelled SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (green), in Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells, showing crosstalk across detector channels (Cy5 near: 650–685 nm, Cy5 far: 685–720 nm); inset, region selected for MINFLUX imaging; size bar, 5 μm; image representative of n = 2 biologically independent experiments. j Two-colour MINFLUX analysis of selected region from (i) after spectral separation, including histogram of nearest neighbour distance between FLUX 680 and Alexa Fluor 647 clusters within the region indicated by dashed box. k Ex-4-induced insulin secretion (fold over 11 mM glucose) in non-targeting Control versus VAPB RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; n = 4 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. Data are mean ± SEM.

The interaction of active GLP-1R with VAPB was deemed functionally relevant, as it was no longer present when VAPB P56S, a self-aggregating loss-of-function VAPB mutant associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)16,17, was expressed instead of its wildtype (WT) counterpart (Supplementary Fig. 1g–i), and as both VAPB knockdown by RNAi (Fig. 1k and Supplementary Fig. 1j, k), and overexpression of VAPB P56S, but not of WT VAPB (Supplementary Fig. 1l), significantly reduced the capacity of GLP-1R to potentiate insulin secretion from INS-1 832/3 cells.

GLP-1R binding to VAPB requires GLP-1R internalisation and is differentially modulated by GLP-1RAs with varying GLP-1R internalisation propensities

To elucidate whether active GLP-1R requires its prior internalisation to engage VAPB, we co-transfected INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells with dominant negative (K44A) mutants of dynamin 1 and 2 to block GLP-1R endocytosis triggered by exendin-4 (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Under these conditions, increased binding of the receptor to VAPB in stimulated versus vehicle conditions was abrogated (Fig. 2a), demonstrating that active GLP-1R interacts with VAPB following its agonist-induced internalisation. Supporting this notion, MS interactomic analyses of GLP-1R co-immunoprecipitates in INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells after a 5-minute stimulation with the endogenous agonist GLP-1, as well as with the exendin-4-based biased GLP-1RAs exendin-F1 and exendin-D3, previously shown to trigger differing degrees of GLP-1R internalisation18,19, resulted in marked differences in the propensity of the receptor to associate with VAPB (Supplementary Fig. 2b), with agonists that trigger robust receptor internalisation (GLP-1, exendin-4, exendin-D3) showing a stronger degree of GLP-1R-VAPB interaction compared to slow GLP-1R-internalising agonist exendin-F1. Marked kinetic differences in GLP-1R-VAPB interaction following exendin-4 versus exendin-F1 stimulation were also demonstrated in INS-1 832/3 cells by a novel NanoBRET assay, with Nanoluciferase-tagged GLP-1R co-expressed with Venus-tagged VAPB (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2c). We extended our analysis to a panel of seven GLP-1RAs, including, as well as exendin-4, exendin-F1 and exendin-D3, fatty acid-modified semaglutide20 and tirzepatide21, as well as small molecules orforglipron22 and danuglipron23. We first tested these GLP-1RAs for their capacity to induce GLP-1R internalisation in purified mouse islets transduced with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-expresssing adenoviruses (Fig. 2c). As previously shown, acute (5-minute) exposure to exendin-4 and exendin-D3 triggered noticeable GLP-1R internalisation, while this was much reduced with the biased agonist exendin-F1. Additionally, and as previously published24, semaglutide triggered a much more robust GLP-1R internalisation than tirzepatide, an agonist that shows a similar degree of GLP-1R GαS bias as exendin-F1. We also detected a clear difference in GLP-1R internalisation triggered by orforglipron versus danuglipron, with the latter showing a similar level of receptor internalisation to that of exendin-4, while the former resulted in reduced receptor internalisation 5 minutes post-agonist exposure. VAPB co-immunoprecipitation using the panel of GLP-1RAs described above unveiled a correlation between the level of GLP-1R–VAPB binding and the degree of receptor internalisation elicited by each of the tested GLP-1RAs (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2d).

a EGFP-VAPB co-IP with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in vehicle (Veh) versus exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells co-expressing control pcDNA3.1+ versus dominant negative dynamin (Dyn)1/2 K44A; n = 1. b Veh-subtracted Ex-4- versus exendin-F1 (Ex-F1)-induced BRET kinetic traces (left) and corresponding AUCs (right) of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-NLuc – Venus-VAPB interactions in INS-1 832/3 cells; n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. c (top), Confocal microscopy analysis of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R localisation in mouse primary islets transduced with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R adenoviruses under Veh conditions or following 5-minute stimulation with the indicated agonists: Ex-4, Ex-F1, exendin-D3 (Ex-D3), tirzepatide (Tirz) and semaglutide (Sema) used at 100 nM; orforglipron (Orf) and danuglipron (Dan) used at 5 μM; size bars, 20 μm; c (bottom), Quantification of residual surface SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R levels in islets from above; n = 3 biologically independent experiments. d Quantification of VAPB co-IP with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells stimulated for 5 minutes with the indicated agonists; n = 3 biologically independent experiments. e VAPB-localised cAMP generation (measured by FluoSTEP) in response to 100 nM Ex-4 versus Ex-F1 stimulation in INS-1 832/3 cells expressing pcDNA3-GFP11(x7)-VAPB + pcDNA3.1(+)-FluoSTEP-ICUE; maximal responses [to forskolin (FSK) + 3-Isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX)] shown; kinetic traces (left) and corresponding AUCs for the agonist-stimulated period (right) shown; n = 5 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. f (top), Ex-4 versus Ex-F1-induced global PKA activity, measured with the global PKA biosensor pcDNA3.1(+)- ExRai-AKAR2 in INS-1 832/3 cells; kinetic traces (left) and corresponding AUCs (right) shown; n = 3 biologically independent experiments; p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. f (bottom), Ex-4 versus Ex-F1-induced mitochondrial PKA activity, measured with the mitochondrial PKA biosensor pcDNA3-mitoExRai-AKAR2 in INS-1 832/3 cells; kinetic traces (left) and corresponding AUCs (right) shown; n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. g, Mitochondrial over global PKA activity, calculated as AUC ratio from data in (f); n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. Data are mean ± SEM.

Exendin-4-stimulated GLP-1R triggers VAPB-localised cAMP generation and PKA activity at the outer mitochondrial membrane

As stated above, besides VAPB, our interactome analysis highlighted several factors enriched for their association with active GLP-1R localised at the ER, mitochondria and/or ERMCSs, a location where VAPB plays a prominent organising role17, suggesting that ERMCSs could be a potential hub for endosomal GLP-1R signalling. To determine if GLP-1R induces cAMP generation specifically at VAPB locations, we modified a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based system of biosensors targeted to endogenous proteins (FluoSTEPs)25, so that a FRET cAMP sensor would fully reconstitute only in the presence of the GFP11 fragment fused to VAPB, resulting in functional biosensor assembly specifically at VAPB loci (Supplementary Fig. 3a). This modified FluoSTEP system was used to measure VAPB-localised cAMP generation in response to either exendin-4 or exendin-F1 stimulation (Fig. 2e). Results in WT INS-1 832/3 cells (expressing endogenous levels of GLP-1R) show VAPB-localised cAMP responses with both agonists, which are less pronounced for the slow internalising exendin-F1 compared to exendin-4, demonstrating that GLP-1R actively signals at VAPB loci. Next, we evaluated whether GLP-1R signalling would also trigger a pool of PKA activity at the surface of mitochondria, a process known to be important for the control of mitochondrial function26. To this end, we employed either a global (whole cell) or a mitochondrially-restricted PKA biosensor expressed at the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM)27 (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Exendin-4 stimulation of WT INS-1 832/3 cells triggered, as expected, a robust global PKA response, which was also evident with the OMM-localised PKA biosensor, demonstrating that GLP-1R stimulation triggers PKA activity at the mitochondrial surface (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Furthermore, utilising the same biosensors as above, we detected reduced OMM-localised, but no change in global, PKA activity with slow internalising exendin-F1 versus exendin-4 (Fig. 2f), leading to increased mitochondrial over global PKA signalling propensity with exendin-4 at this acute (5-minute) stimulation time-point (Fig. 2g). This, together with the VAPB-localised cAMP FluoSTEP results from above, indicates that GLP-1R internalisation is important for GLP-1R-induced cAMP generation at VAPB loci and PKA signalling at OMMs, at least acutely.

Exendin-4-stimulated GLP-1R associates with ERMCSs

To examine the potential docking of GLP-1R-positive endosomes to ERMCSs, we employed a split-GFP-based contact site sensor (SPLICS)28 to specifically visualise ERMCSs in conjunction with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in vehicle versus exendin-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells (Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Movie 2). This approach allowed us to observe an intimate association between GLP-1R-positive endosomes and ERMCSs over time, validating our hypothesis. Additional cell labelling with fluorescent MitoTracker prior to exendin-4 exposure showed SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R extensively colocalised with EGFP-VAPB in proximity to mitochondria, an organelle with which VAPB is known to interact (Fig. 3d).

a Confocal microscopy analysis of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (red) co-localisation with ERMCSs (SPLICS Mt-ER Long P2A, green) in vehicle (Veh, left) versus exendin-4 (Ex-4, right)-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells; size bars, 10 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. b SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R - SPLICS Mt-ER Long P2A co-localisation (Mander’s coefficient) in Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions from data in (a); n = 5 cells from 3 independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed unpaired t-test. c Time-lapse confocal microscopy analysis of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R–ERMCS association, imaged as in (a); arrows indicate co-localised spots; time post-Ex-4 addition indicated; size bar, 10 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. d Confocal microscopy analysis of EGFP-VAPB (blue), mitochondria (MitoTracker Red, green) and SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (SNAP-Surface Alexa Fluor 647, red) in an Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cell; size bar, 10 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. e Single confocal slice from an Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cell, with signals for EGFP-VAPB (green), SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (yellow), mitochondria (magenta), and DAPI (blue) shown; white arrow points to a SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-positive endosome used for CLEM analysis; size bar, 10 µm; also included CLEM overlay of aligned confocal slice with corresponding single slice of an EM tomogram (size bar, 10 µm) and magnification of EM tomogram slices (size bar, 1 µm) with indicated SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-positive endosome (black arrow); images representative of n = 2 cell regions from the same biological experiment. f 3D rendering of segmentation of data from (e), with VAPB-positive ER (purple), mitochondria (orange) and SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-positive endosome (yellow) shown; Created with ORS Dragonfly. g TEM micrograph of a 70 nm ultrathin section from resin embedded mouse islets transduced with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R adenovirus, with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R labelled with SNAP-Surface biotin + Alexa Fluor 488 Streptavidin, 5 nm colloidal gold prior to Ex-4 stimulation and fixation; ER (blue), mitochondria (yellow) and SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-positive endosome (pink); inset shows magnified endosome area containing 5 nm gold particles; size bars, 100 nm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. Data are mean ± SEM.

Further high-resolution 3D imaging to confirm endosomal GLP-1R localisation to ERMCSs included in situ correlative light and electron microscopy (CLEM) at room temperature to correlate ultrastructural features with positive fluorescent signals for SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R, EGFP-VAPB and mitochondria. To this end, INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells were labelled at the cell surface with a membrane impermeable fluorescent SNAP-tag probe prior to exendin-4 stimulation, with correlation of the confocal slice to the corresponding TEM tomogram (Fig. 3e) revealing two mitochondrial volumes in close contact with EGFP-VAPB-positive ER, itself docked to a vesicle positive for SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R, indicative of a GLP-1R-positive endosome (Fig. 3f and Supplementary Movie 3). Similar results were obtained using a cryo-CLEM approach, with a SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R endosome docked to the EGFP-VAPB-positive ER network, itself in contact with a nearby mitochondrion, following correlation of cryo-confocal and cryo-FIB-SEM data (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c).

These results were further replicated using an immuno-EM approach in primary mouse islets transduced with a SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-expressing adenovirus by labelling cell surface SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in living islets with membrane-impermeable SNAP-biotin followed by 5 nm gold-conjugated streptavidin prior to exendin-4 stimulation and TEM processing. TEM imaging of ultrathin (70 nm) sections from the resin-embedded islets from above revealed 5 nm gold-positive endosomes (indicative of the presence of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R) forming contacts with the ER, itself contacting nearby mitochondria (Fig. 3g).

Active GLP-1R interacts with the PKA-RI-recruiting AKAP SPHKAP at ERMCSs via VAPB

Amongst the interactors enriched for active GLP-1R binding in our MS interactome analysis, we identified both PKA-RIα/β and the A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) SPHKAP, a paralog of AKAP11 (also known as AKAP220) that binds to two RIα subunits of the PKA holoenzyme29. Both SPHKAP and AKAP11 harbour a FFAT (two phenylalanines in an acidic tract) motif30,31, a specific short protein sequence that binds to the Major Sperm Protein (MSP) domain of VAPs (Supplementary Fig. 5a), which, in the case of SPHKAP, can be regulated by phosphorylation (phosphoFFAT, or pFFAT)31. Agreeably, SPHKAP has previously been shown to interact with VAP proteins in neurons and assemble functionally relevant PKA-RI biomolecular condensates at VAPA/B-positive ER locations32,33. SPHKAP is expressed in metabolically relevant tissues, including pancreatic islets and intestinal K and L cells, and has been previously shown to play important roles in both incretin secretion from the gut and incretin-dependent glucoregulation34,35. Additionally, we found SPHKAP mRNA expression to be decreased in a published RNA-Seq database of islets from db/db versus WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 5b), and meta-analyses from four separate genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in humans uncovered genome-wide significant associations between SPHKAP gene variants, T2D risk, and high BMI36,37,38,39 (Supplementary Fig. 5c, d). We found the effect of SPHKAP gene variants in T2D versus high BMI to be tightly correlated (Supplementary Fig. 5e), suggesting a shared mechanism of action for SPHKAP in both disorders where GLP-1RAs are also known to be effective. Our own genetic analysis also demonstrated a significant association between SPHKAP gene coding variants and random blood glucose levels in whole exome sequencing (WES) data from UK Biobank (UKBB) individuals without diabetes (Supplementary Fig. 5f), strongly supporting a role for SPHKAP in the regulation of β-cell function.

We therefore next investigated the potential involvement of SPHKAP/PKA-RI in GLP-1R signal transduction from ERMCSs. We first confirmed active GLP–1R–SPHKAP protein-protein interaction, inferred from our MS interactome analysis, by measuring increased co-immunoprecipitation of SPHKAP-EGFP (Fig. 4a, b, Control RNAi conditions; Supplementary Fig. 6a), as well as of endogenous SPHKAP (Supplementary Fig. 6b), with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in exendin-4-stimulated versus vehicle-treated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells. Interestingly, we also detected a similar association between the other incretin receptor, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor (GIPR), and endogenous SPHKAP following GIP stimulation of INS-1 832/3 cells stably expressing SNAP/FLAG-hGIPR (Supplementary Fig. 6c), suggesting that this localised PKA signalling module is shared between both incretin receptors.

a SPHKAP-EGFP co-IP with SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R in Control versus VAPB RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells under vehicle (Veh) versus exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated conditions; blots representative of n = 5 biologically independent experiments; GFP-positive fragments detected due to intrinsic instability of co-IPed full-length fusion protein. b Quantification of SPHKAP-EGFP over SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R levels from (a); n = 5 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. c Confocal microscopy analysis of SPHKAP-EGFP versus mitochondria (imaged with MitoTracker Red) localisation in INS-1 832/3 cells treated with Control versus VAPB RNAi; size bars, 5 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. d Confocal microscopy analysis of SPHKAP-EGFP versus ER (imaged with ER-Tracker Red) localisation in INS-1 832/3 cells; size bar, 10 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. e SPHKAP-EGFP co-localisation (Mander’s coefficient) with mitochondria (Mito) versus ER; n = 5 cells from 3 independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed unpaired t-test. f Ex-4-stimulated cAMP responses in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells, measured with cADDis cAMP biosensor; left, cAMP traces; right, AUC quantification; n = 3 biologically independent experiments; p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. g Ex-4-stimulated global PKA responses in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; left, PKA traces; right, AUC quantification; n = 4 biologically independent experiments; p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. h Ex-4-stimulated mitochondrial PKA responses in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; left, PKA traces; right, AUC quantification; n = 4 biologically independent experiments; p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. i, VAPB-localised PKA activity (measured by FluoSTEP) in response to 100 nM Ex-4 stimulation in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells expressing pcDNA3-GFP11(x7)-VAPB + pcDNA3.1(+)-FluoSTEP-AKAR; maximal responses (to FSK + IBMX) shown; kinetic traces (left) and corresponding AUCs for the agonist-stimulated period (right) shown; n = 5 biologically independent experiments; p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. Data are mean ± SEM.

We next determined that the exendin-4-induced GLP-1R–SPHKAP interaction requires VAPB, as it is abrogated by VAPB knockdown (Fig. 4a, b, VAPB RNAi conditions; Supplementary Fig. 6a). Confocal analysis of SPHKAP-EGFP localisation in WT INS-1 832/3 cells revealed that, in contrast with a previous report suggesting mitochondrial localisation40, SPHKAP localises to an intracellular network occasionally in contact with, but not inside, mitochondria (Fig. 4c, Control RNAi panels; Supplementary Fig. 6d). Indeed, labelling of ER with the fluorescent dye ER-Tracker revealed the punctate localisation of SPHKAP-EGFP along ER membranes (Fig. 4d, e), in agreement with recent reports which also indicate SPHKAP localisation and PKA-RI targeting to the ER32,33. Also in agreement with these reports, the localisation of SPHKAP-EGFP to ER loci required VAPB, as it was lost in VAPB RNAi-treated cells (Fig. 4c, VAPB RNAi panels). We next generated a mutant version of SPHKAP-EGFP harbouring a point mutation in its pFFAT motif (SPHKAP-EGFP A215E, DFLTASE to DFLTESE). This strategy was based on previous structural data showing that position 5 of the FFAT core motif is located within a hydrophobic pocket in the MSP domain of VAP41, with previous studies indicating that introducing a negative charge in this position causes a steric hindrance which effectively disrupts FFAT motif—VAP interaction42. Agreeably, our SPHKAP-EGFP pFFAT mutant lost both its binding to exendin-4-stimulated SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R (Supplementary Fig. 6e) and its localisation to the ER network (Supplementary Fig. 6f). We additionally demonstrated the co-existence of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R, VAPB and SPHKAP in mitochondria-associated membranes (MAMs) purified from exendin-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells (Supplementary Fig. 6g), and a protein-protein interaction between SPHKAP and EGFP-VAPB in the same cells (Supplementary Fig. 6h). Taken as a whole, these results demonstrate the association of SPHKAP with active GLP-1R at ERMCSs in a VAPB-dependent manner via the pFFAT motif of SPHKAP.

ERMCS-localised GLP-1R-dependent PKA signalling requires SPHKAP

We next tested the effect of SPHKAP downregulation on GLP-1R-dependent downstream signalling. SPHKAP knockdown efficiency in INS-1 832/3 cells was validated against both endogenous SPHKAP (Supplementary Fig. 6i) and SPHKAP-EGFP (Supplementary Fig. 6j). Loss of SPHKAP did not affect the interaction between the receptor and VAPB (Supplementary Fig. 7a-c), indicating that GLP-1R is recruited to VAPB-positive ERMCSs independently of SPHKAP. Loss of SPHKAP also did not affect the capacity for the receptor to generate cAMP following exendin-4 stimulation of WT INS-1 832/3 cells (Fig. 4f). In contrast, while global PKA responses to exendin-4 were not affected (Fig. 4g), exendin-4-induced OMM-localised PKA activity was blunted by SPHKAP downregulation (Fig. 4h). Finally, we employed a similar modified FluoSTEP system to the one shown in Fig. 2, but this time adapted to assess VAPB-localised PKA activity in response to exendin-4 stimulation in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated WT INS-1 832/3 cells (see Supplementary Fig. 7d for a schematic of this method). Results showed that exendin-4 stimulation triggers VAPB-localised PKA activity in WT INS-1 832/3 cells, and that this activity requires SPHKAP (Fig. 4i), presumably via SPHKAP binding to PKA-RI and assembly of a PKA signalling hub at ERMCSs. Consequently, we could observe the appearance of PKA-RIα-EGFP-positive puncta, indicative of liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and biomolecular condensate assembly25, in exendin-4-stimulated WT INS-1 832/3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 7e).

Control of mitochondrial and β-cell function by SPHKAP-dependent GLP-1R signalling

We next assessed the effect of ERMCS-localised GLP-1R-induced PKA signalling in the control of mitochondrial function in INS-1 832/3 cells. Exendin-4 stimulation triggered a small increase in mitochondrial membrane potential under 6 mM glucose conditions, with this response further enhanced under increased (20 mM) glucose concentrations. Both membrane potential rises were significantly reduced in SPHKAP RNAi-treated versus Control WT INS-1 832/3 cells (Fig. 5a). Accordingly, we observed a loss of ATP tone in exendin-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 cells following SPHKAP knockdown (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 7f), suggesting a defect in mitochondrial respiration. We further determined the impact of ERMCS-localised GLP-1R signalling on β-cell function by analysing acute insulin secretion responses and β-cell survival to ER stress downstream of GLP-1R stimulation in SPHKAP RNAi-treated versus Control WT INS-1 832/3 cells. Exendin-4-stimulated insulin secretion was significantly reduced in SPHKAP RNAi versus control conditions (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 7g), without any effect of SPHKAP over-expression in this parameter (Supplementary Fig. 7h). Additionally, the anti-apoptotic effect of exendin-4 in cells exposed to thapsigargin (to trigger ER stress) was blunted following SPHKAP knockdown (Fig. 5d). Finally, we measured exendin-4-induced mitochondrial and ER Ca2+ responses in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated WT INS-1 832/3 cells. Increases in both ER and mitochondrial Ca2+ in response to exendin-4 stimulation were apparent in these cells. However, while ER responses were not affected by SPHKAP knockdown, we detected a delay in the mitochondrial Ca2+ response peak time in SPHKAP RNAi versus Control RNAi-treated WT INS-1 832/3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 7i, j).

a Exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells, measured with TMRE; left, membrane potential traces; G20, 20 mM glucose; right, quantification of AUCs during the Ex-4 and G20 periods; n = 5 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. b Ex-4-stimulated ATP level in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells, measured with the cyto-Ruby3-iATPSnFR1.0 biosensor; left, ATP traces; right, AUC quantification; n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. c Ex-4-induced insulin secretion (fold over 11 mM glucose) in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by two-tailed paired t-test. d Percentage of apoptosis ± thapsigargin exposure in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells under vehicle (Veh) versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions; n = 3 biologically independent experiments; p value as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. e PKA-dependent phosphorylation of MIC19-3xHA in INS-1 832/3 cells under Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions, determined by western blotting of anti-HA immunoprecipitates with an anti-RRx-pS/T antibody; FSK, positive control for PKA activation; left, representative blots; right, quantification of phospho-MIC19 levels; n = 3 to 4 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. f Ex-4-induced mitophagy, measured as changes in ratio fluorescence intensities (580/440 nm) over time with the dual-excitation ratiometric biosensor mKeima-Red-Mito-7 in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; n = 6 biologically independent experiments. g Time-lapse confocal microscopy imaging of Drp1 localisation to mitochondria in Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated INS-1 832/3 cells; mitochondria (mito-BFP, blue) and Drp1 (mCherry-Drp1, red); arrows indicate Drp1-positive spots on mitochondria; time post-Veh or Ex-4 exposure indicated; size bars, 5 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. h, Changes in Drp1 phosphorylation at Ser616 following Ex-4 stimulation of Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; left, representative blots; right, quantification; n = 4 biologically independent experiments; p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. Data are mean ± SEM.

As SPHKAP has previously been shown to bind to the mitochondrial cristae junction regulator and MICOS complex component MIC1940, a prominent PKA substrate involved in both cristae assembly during mitochondrial remodelling43 and in regulation of ERMCSs, we next tested whether exendin-4 stimulation would trigger MIC19 phosphorylation in WT INS-1 832/3 cells using a MIC19 immunoprecipitation strategy coupled with western blotting with an antibody against PKA phosphosites (RRxpS/T)44. Exendin-4 exposure resulted in a significant increase in PKA-specific MIC19 phosphorylation, an effect that was potentiated by the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin (Fig. 5e). Dual knockdown of SPHKAP and VAPB in INS-1 832/3 cells led to widespread changes in PKA phosphorylation of several MICOS complex components downstream of GLP-1R activation, suggesting that ERMCS-localised GLP-1R signalling modulates the activity of the MICOS complex (Supplementary Fig. 7k).

Control of mitochondrial morphology by SPHKAP-dependent ERMCS-localised GLP-1R signalling

As the main role of the MICOS complex is to orchestrate mitochondrial cristae assembly45, and MIC19 plays an important role in the transfer of lipid precursors across ERMCSs during mitochondrial remodelling10, we next assessed whether GLP-1R stimulation would play a role in mitochondrial remodelling processes in INS-1 832/3 cells, and whether this would be affected by SPHKAP knockdown. We first investigated if acute exendin-4 stimulation triggers changes in mitochondrial turnover. Despite no detectable changes in mitochondrial DNA copy number after 30 minutes of exendin-4 exposure in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated, or in GLP-1R KO INS-1 832/3 cells (Supplementary Fig. 7l), acute (10-minute) stimulation of WT INS-1 832/3 cells with exendin-4 triggered increased mitophagy, assessed using an mKeima-based assay, an effect not present following SPHKAP downregulation (Fig. 5f). Further evidence of exendin-4-induced mitophagy was obtained by CLEM analysis of INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells, where we could find instances of SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R-positive endolysosomes surrounded by mitochondria (Supplementary Fig. 8a,b). We also detected increased recruitment of the mitochondrial fission protein mCherry-Drp1 to mito-BFP-expressing mitochondria in exendin-4-stimulated versus vehicle-exposed WT INS-1 832/3 cells (Fig. 5g, Supplementary Fig. 8c, Supplementary Movies 4 and 5). Drp1 phosphorylation at Serine 616, which, unlike Serine 63746, is important for regulating mitochondrial fission and is not directly PKA-dependent47,48, was, as expected, not modified by acute exendin-4 exposure in Control RNAi-treated cells, but was progressively lost 15 minutes post-exendin-4 stimulation in SPHKAP RNAi-treated WT INS-1 832/3 cells (Fig. 5h).

We next directly assessed changes in mitochondrial morphology by confocal microscopy imaging of MitoTracker-labelled mitochondria in vehicle versus exendin-4-stimulated WT INS-1 832/3 cells. Here, we employed a similar approach to49 to manually score cells by mitochondrial phenotype into three categories: long tubular (referred to as “hyperfused”), intermediate/short tubular (referred to as “tubular”) and fragmented. Results showed that 10 minutes of exendin-4 exposure completely remodels the mitochondrial network from a predominantly hyperfused to a fragmented phenotype (Fig. 6a). As expected, and serving as validation of our classification approach, this remodelling did not take place in INS-1 832/3 cells lacking GLP-1R (GLP-1R KO) (Fig. 6b). We further confirmed our results by re-analysing the data from above using the automated Mitochondria Analyzer plugin in Fiji to determine changes in mitochondrial form factor, which provides information on mitochondrial shape, as well as mitochondrial mean area (Supplementary Fig. 8d). Agreeably, we found a significant reduction on mitochondrial form factor and mean area, indicative of remodelling, upon exendin-4 stimulation of WT INS-1 832/3, but not of INS-1 832/3 GLP-1R KO cells.

a Confocal microscopy analysis of mitochondrial morphology in vehicle (Veh) versus exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated WT INS-1 832/3 cells; top, representative images with mitochondria labelled with MitoTracker Red; size bars, 10 μm; bottom, percentage of cells classified as presenting hyperfused, tubular or fragmented mitochondria per condition; n = 4 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. b As in (a) for INS-1 832/3 GLP-1R KO cells; n = 4 biologically independent experiments; p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. c As in (a) for Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells under Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions; n = 5 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. d Maximum intensity projections (MIP) from confocal z-stacks of mitochondria in vehicle (Veh) versus Ex-4-stimulated Control and SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells; size bars, 10 µm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. e Mitochondrial morphology in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells under Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions, imaged by super-resolved STED microscopy; size bars, 2 μm. Images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. Data are mean ± SEM.

Next, we performed mitochondrial morphology analysis of WT INS-1 832/3 cells treated with Control versus SPHKAP RNAi prior to vehicle or exendin-4 exposure (Fig. 6c). While exendin-4 triggered a similar degree of mitochondrial network remodelling as above in Control RNAi-treated cells, SPHKAP knockdown resulted in disrupted mitochondrial morphology at vehicle conditions, which somewhat resembled that of exendin-4-stimulated Control RNAi-treated cells in terms of tubularity but had further visual abnormalities. Moreover, exendin-4 stimulation had no further effect on the mitochondrial morphology of SPHKAP RNAi-treated cells. These results were validated with the Mitochondria Analyzer plugin in Fiji, which showed reduced mitochondrial form factor and mean area following exendin-4 exposure of Control RNAi-treated cells, with SPHKAP RNAi-treated cells under vehicle conditions showing similar values to those of exendin-4-stimulated control cells (Supplementary Fig. 8e). However, with this analysis method, we also detected an apparent increase in form factor and mitochondrial mean area in exendin-4-stimulated versus vehicle-treated SPHKAP RNAi-treated cells, an effect opposite to that triggered by exendin-4 in control conditions.

To better visualise the changes in mitochondrial morphology under these different conditions, we performed z-series analysis of confocal sections across whole cells, represented as MIPs in Fig. 6d, as well as STED microscopy analysis of mitochondrial morphologies using the fixable STED-compatible mitochondrial dye PKmito ORANGE FX (Fig. 6e), with Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated cells showing similar changes in mitochondrial morphology as those described above.

Finally, we performed high-resolution TEM imaging for precise quantification of mitochondrial area and number of cristae per mitochondria in ultrathin (70 nm) sections on resin-embedded Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated WT INS-1 832/3 cells, as well as INS-1 832/3 GLP-1R KO cells, both under vehicle conditions and following exendin-4 stimulation. In agreement with our previous results, we measured an exendin-4-induced reduction in both parameters in Control RNAi-treated cells, but no change in response to exendin-4 in either SPHKAP RNAi-treated or in GLP-1R KO cells (Fig. 7a, b). Interestingly, the mitochondrial morphology changes triggered by exendin-4 in Control RNAi-treated cells were accompanied by a significant reduction in ERMCS length, which appeared already reduced under vehicle conditions without further effect of exendin-4 following SPHKAP downregulation or in GLP-1R KO cells, with no apparent effect of SPHKAP-EGFP overexpression in INS-1 832/3 cells in this parameter (Fig. 7c). This ERMCS length reduction was accompanied by a reduced number of ERMCSs per mitochondrial area in exendin-4-stimulated versus vehicle-exposed WT INS-1 832/3 cells, assessed using a splitFAST approach as in ref. 50 (Fig. 7d, e).

a TEM micrographs of resin-embedded ultrathin sections depicting mitochondrial morphology in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells, and INS-1 832/3 GLP-1R KO cells, under vehicle (Veh) versus exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated conditions; size bars, 100 nm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. b Quantification of mitochondrial area and number of cristae per mitochondria from ∼20 TEM micrographs per condition per experimental repeat from (a); n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. c Quantification of ERMCS length in Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated INS-1 832/3 cells and INS-1 832/3 GLP-1R KO cells from (a), as well as in Veh versus Ex-4-treated SPHKAP-EGFP-expressing WT INS-1 832/3 cells; p values as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. d Confocal images of WT INS-1 832/3 cells co-expressing the mitochondrial marker 4xMTS-Halo (green) and splitFAST reporters ER-RspA-NFAST and OMM-short-RspA-CFAST, labelled with a Lime splitFAST ligand to detect ERMCSs (magenta) under Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions; size bars, 5 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. e Quantification of the number of ERMCSs per mitochondrial area from data in (d); results per cell (left) and per independent repeat (right) shown; 50–57 cells imaged from n = 3 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-tailed unpaired t-tests. Data are violin plots or mean ± SEM.

GLP-1R localisation and GLP-1R-induced PKA signalling at ERMCSs in primary mouse and human islets

To validate the interaction of GLP-1R with VAPB and SPHKAP at ERMCSs in a physiologically relevant setting with endogenous levels of receptor expression, proximity ligation assays (PLAs) were performed in purified mouse primary islets using one of the few existing validated mouse GLP-1R antibodies from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank51,52,53, with GLP-1R–VAPB and GLP-1R–SPHKAP interactions readily observed in exendin-4-stimulated islets (Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 9a). To verify that these interactions are present within pancreatic β-cells, we counterstained both vehicle and exendin-4-stimulated islets for insulin (Supplementary Fig. 9b). Next, to analyse the functional impact of SPHKAP downregulation on islet function, we employed a lentiviral shRNA approach to knock down SPHKAP on intact islets, as most functional outputs from primary islets cannot be optimally recapitulated with dispersed islet cells due to the loss of important intra-islet cell-cell interactions. Lentiviral transduction of cells within intact islets is restricted to the outermost islet cell layers so that only a small fraction of cells (which we estimate at ~25% of the total) is effectively transduced. However, those represent a higher functional cell pool due to necrosis of the islet core in non-vascularised isolated islets54, so that it is still possible to assess potential functional differences from a relatively small percentage of transduced cells. Accordingly, we could only detect a tendency for reduced SPHKAP mRNA levels in whole islets transduced with SPHKAP versus Control shRNA lentiviruses (Supplementary Fig. 9c), which nevertheless suggests a good level of downregulation from the pool of transduced cells. We next analysed some key signalling outcomes from these islets. As for INS-1 832/3 cells, ATP levels in exendin-4-stimulated versus vehicle-treated islets were reduced with SPHKAP shRNA (Fig. 8b). Exendin-4 exposure also led to a significant reduction in the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in Control shRNA islets exposed to thapsigargin, but this effect was no longer present in SPHKAP shRNA-transduced islets, which presented with basally higher ROS levels than the corresponding control islets (Fig. 8c). Finally, while the effect of SPHKAP knockdown in the acute potentiation of insulin secretion triggered by exendin-4 in these islets was mild, we found a small but significant increase in insulin secretion at 11 mM glucose alone in SPHKAP versus Control shRNA-transduced islets (Fig. 8d, left), which led to a near-significant reduction in exendin-4-induced insulin secretion fold (Fig. 8d, right), an effect which agrees with previously published results in a SPHKAP KO mouse model, with increased insulin secretion under glucose alone conditions but dampened incretin responses in islets from these mice34.

a PLA showing interactions between endogenous GLP-1R and VAPB (left) or SPHKAP (right) in exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated primary mouse islets; size bars, 20 μm; images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments. b Ex-4-induced changes in ATP levels per total protein in lysates from Control versus SPHKAP shRNA-transduced primary mouse islets; n = 5 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. c Ex-4-induced changes in thapsigargin-triggered ROS accumulation per cell in Control versus SPHKAP shRNA-transduced primary mouse islets; n = 6 biologically independent experiments, p value as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test. d Ex-4-induced potentiation of insulin secretion in Control versus SPHKAP shRNA-transduced primary mouse islets; n = 9 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by one-way ANOVA with Šidák post-hoc test; fold over 11 mM glucose also shown, p value as indicated by two-tailed ratio paired t-test. Data are mean ± SEM.

We next assessed changes in mitochondrial morphology in intact mouse islets by confocal imaging of mitochondria from the outermost layer of islet cells, to maximise our chances of recording phenotypes from lentivirally transduced cells. We used a similar approach as in INS-1 832/3 cells to segment and classify islet cells as predominantly presenting a hyperfused, tubular or fragmented mitochondrial phenotype (see Supplementary Fig. 9d for an example of our method of islet segmentation and cell classification). Cells in WT mouse islets presented a similar distribution of mitochondrial morphologies as in INS-1 832/3 cells, with mitochondria primarily hyperfused or tubular under vehicle conditions but remodelling towards a more fragmented phenotype following exendin-4 exposure (Fig. 9a). Islets extracted from GLP-1R KO mice presented a higher level of hyperfused mitochondria that did not undergo remodelling with exendin-4 (Fig. 9b). As in INS-1 832/3 cells, transduction of WT islets with SPHKAP shRNA-expressing lentiviruses triggered a change in mitochondrial morphology under vehicle conditions, with a higher degree of fragmentation versus control islets and no effect of exendin-4 exposure following SPHKAP downregulation (Fig. 9c).

a Confocal microscopy analysis of mitochondrial morphology in vehicle (Veh) versus exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated WT primary mouse islets; top, representative images with MitoTracker Red-labelled mitochondria; size bars, 20 μm; bottom, percentage of islet cells classified as presenting hyperfused, tubular or fragmented mitochondria per condition; n = 5 biologically independent experiments (islet preps from separate mice), p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. b As in (a) for islets from GLP-1R KO mice; n = 5 biologically independent experiments; p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. c As in (a) for Control versus SPHKAP shRNA-transduced mouse islets under Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions; n = 6 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. d As in (a) for Control versus SPHKAP RNAi-treated dispersed primary mouse islet cells under Veh versus Ex-4-stimulated conditions; size bars, 5 μm; n = 4 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. Data are mean ± SEM.

We also performed mitochondrial morphology assessments in dispersed islet cells from mice transfected with Control versus SPHKAP siRNA, which responded similarly to intact islets in terms of increased mitochondrial fragmentation following exendin-4 exposure in control conditions, but showed disturbed mitochondrial morphology under vehicle conditions and no further effect of exendin-4 exposure in SPHKAP siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 9d). These phenotypic changes were still present when assessed as changes in mitochondrial form factor and mean area using the Mitochondria Analyser Fiji plugin (Supplementary Fig. 9e).

Lastly, we repeated some of our assessments with human donor islets. PLA assays again demonstrated interactions between endogenous GLP-1R, VAPB and SPHKAP in exendin-4-stimulated human islets (Fig. 10a, b). As in mouse islets, assessment of mitochondrial morphology by confocal microscopy analysis in intact human islets revealed predominantly hyperfused mitochondria under vehicle conditions, which was rapidly remodelled by acute exendin-4 exposure to a more fragmented morphology (Fig. 10c, d).

a PLA showing interactions between endogenous GLP-1R and VAPB (left) or SPHKAP (right) in exendin-4 (Ex-4)-stimulated primary human islets; size bars, 20 μm. Images representative of n = 3 biologically independent experiments (islets from independent donors). b Negative control (no primary antibody) for PLA data shown in (a); nuclei (DAPI), blue; size bar, 20 µm. c Confocal microscopy analysis of mitochondrial morphology in vehicle (Veh) versus Ex-4-stimulated primary human islets; mitochondria labelled with MitoTracker Red; size bars, 20 μm; inset, magnification areas; images representative of n = 5 biologically independent experiments (islets from independent donors). d Percentage of human islet cells classified as presenting hyperfused, tubular or fragmented mitochondria per condition; n = 5 biologically independent experiments, p values as indicated by two-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc test. Data are mean ± SEM.

Discussion

Mitochondrial malfunction is a prominent feature of diabetes, encompassing defects in mitochondrial structure and dynamics, ROS overproduction and apoptosis, breakdown of nutrient sensing and metabolic uncoupling55,56, with strong backing evidence from human genetic studies57,58,59. Mitochondrial quality control mechanisms have been recently found to control cellular identity and maturity in metabolically relevant tissues60, including in pancreatic β-cells, highlighting the importance that mitochondria have in the control of β-cell function. Strategies to correct the detrimental effect of T2D in affected tissues are therefore likely to involve amelioration of mitochondrial function; GLP-1RAs are no exception, with numerous reports highlighting their capacity to potentiate mitochondrial quality control mechanisms and improve mitochondrial health5,6,7,8, with mitochondrial regulation potentially key to explain their beneficial effects in metabolic tissues.

Despite the accumulating evidence around pathways engaged by the GLP-1R and other GPCRs in target tissues, there is still substantial uncertainty about the precise molecular mechanisms involved, particularly with regards to the spatiotemporal organisation of their signalling and their presence in spatially restricted subcellular (or even suborganelle) signalling hubs or nanodomains61. In this context, the study of MCSs has become an area of considerable importance to understand the spatial architecture of signalling, with recent reports recognising their prominent role in pancreatic β-cells for key processes ranging from insulin granule biogenesis to calcium homoeostasis62,63,64. In this study, we took an unbiased approach to unveil molecular partners working in concert with the GLP-1R to control β-cell function, finding not only that the receptor engages with ER-endosome MCSs to organise its signalling, but that the main constituents of these inter-organelle contacts, namely the VAPs, are by a considerable margin the most prominent intracellular binding partners of active GLP-1R. This suggests that engagement of VAPs and subsequent generation of ER-localised GLP-1R signalling is not just one of many pathways employed by the receptor, but the main site of action of endosomal GLP-1R following its internalisation from the plasma membrane.

This also suggests that GLP-1RAs with distinct rates of receptor internalisation and lysosomal targeting might differentially regulate the kinetics of this engagement, so that slow GLP-1R internalising compounds are expected to trigger initially reduced VAPB interactions, which might however paradoxically result in prolonged VAPB engagement over time, and therefore potentially lead to sustained ER signalling, as these biased compounds are also associated with reduced lysosomal degradation from the pool of internalised receptors18,24. Of note, we have found here a similar protein-protein interaction between SPHKAP and GIP-stimulated GIPR, suggesting that compounds such as tirzepatide, which target the GLP-1R as a biased, but the GIPR as a balanced agonist, might present with an optimal signalling profile by means of maximising prolonged plasma membrane signalling from the GLP-1R while at the same time engaging in GIPR-dependent acute ER signalling.

In the present study, we have not only unveiled the interaction of endosomal GLP-1R with the ER, but also its localisation to VAPB-containing ERMCSs, from where the receptor assembles a newly described PKA signalling nanodomain, enabling cAMP-dependent PKA activation at the interface between the ER and mitochondria. This ERMCS-localised GLP-1R signalling hub requires the engagement of the AKAP SPHKAP, known to assemble PKA-RIα aggregates at the ER32,33, with VAPB playing a central role as the tethering factor responsible for the separate recruitments of GLP-1R and SPHKAP to ERMCSs, the latter via the direct interaction of VAPB with the pFFAT motif of SPHKAP. It is important to highlight that SPHKAP is one of a few AKAPs known to recruit PKA-RI instead of RII subunits40. This is highly relevant as PKA-RIα aggregates undergo LLPS to form biomolecular condensates65 which spatially restrict PKA activity, leading to signal compartmentalisation25, explaining why the direct presence of endosomal GLP-1R at ERMCSs is required to assemble this signalling hub, and uncovering a new modality of GLP-1R signal transduction which involves the local assembly of a biomolecular condensate containing not only signalling mediators such as SPHKAP/PKA, and also presumably adenylate cyclase, but also downstream targets for PKA phosphorylation such as the MICOS complex and other ERMCS components, some likely found amongst the active GLP-1R interactors identified in our interactome analysis. An additional level of regulation could be provided by kinases and/or phosphatases controlling VAPB/SPHKAP/PKA-RIα assembly/disassembly, such as DYRK1A, recently shown to be recruited to VAPB/SPHKAP/PKA-RIα condensates in neurons33 and previously identified in a kinome study to be regulated by GLP-1R activity66, as well as by the autophagic degradation of the VAPB/SPHKAP/PKA-RIα complex via VAPB/SPHKAP interaction with its paralog AKAP11 and GSK3α/β, a pathway recently shown in neurons to control neurotransmission, and to be defective in AKAP11-associated psychiatric disorders33.

The abovementioned signalling hub appears to be equally important for the control of β-cell function, a notion supported by human genetic data of genome-wide significance unveiling an association between SPHKAP gene variants, random blood glucose levels/T2D, and high BMI. As we observe a correlation between SPHKAP variant effects in T2D and high BMI (as a proxy for obesity), we propose here that SPHKAP might play a pleiotropic role in both disorders by the engagement of common signalling pathways in different tissues. These could involve the GLP-1R, known to signal in anorectic neurons to regulate food intake as well as in β-cells to potentiate insulin secretion and β-cell survival67, as well as other metabolically relevant GPCRs, via VAPB engagement in tissues where this AKAP is expressed, including the pancreas, brain and heart29,32. For example, this mechanism might potentially regulate liver mitochondrial function, a possibility supported by the previously published interaction between the closely related glucagon receptor and VAPB in hepatocytes68. The ERMCS-localised signalling hub identified here is therefore likely to mediate the action of multiple GPCRs, for example, GIPR, as also shown here. Agreeably, beyond the effect observed in exendin-4-induced responses, we find a significant impact of SPHKAP downregulation in mitochondrial morphology and other parameters already present under vehicle conditions.

Another outcome of the present study is the identification of the MICOS complex component MIC19 as a downstream target of ERMCS-localised GLP-1R-induced PKA phosphorylation. MIC19 is not only a key member of mitochondrial cristae junctions, responsible for the organisation of mitochondrial inner and outer membrane contacts and architecture of respiratory complexes and the proton pump, but also plays a prominent role in the transfer of lipid precursors across ERMCSs for the biosynthesis of the key mitochondrial lipid cardiolipin69, therefore connecting mitochondrial cristae organisation with the generation of membrane curvature and control of mitochondrial function afforded by this lipid10. We therefore hypothesise that the GLP-1R-dependent phosphorylation of MIC19 at ERMCSs might not only highlight a direct role for the receptor in the control of mitochondrial dynamics, but also regulate lipid precursor transfer across ERMCSs to sustain mitochondrial turnover. This is particularly relevant as alterations in cardiolipin profiles have been reported in several diseases where GLP-1RAs play beneficial roles, including Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, obesity, and T2D70. Interestingly, our MS interactomic analysis also identifies TAMM41, an essential enzyme for the biosynthesis of cardiolipin71, as an active GLP-1R interactor.

Amongst the mitochondrial processes modulated by SPHKAP-dependent ERMCS-localised GLP-1R cAMP/PKA signalling, we have found acute increases in mitochondrial fission and mitophagy, two key quality control mechanisms which enable the clearance of damaged, unhealthy, or old mitochondria, and hold a prominent role in the maintenance of β-cell function56 and identity60. Loss of these functions can lead to impaired insulin release and glucose intolerance72, with the present study indicating that controlling these processes is an important mechanism engaged by the GLP-1R to exert its beneficial action on β-cell function and survival under oxidative stress conditions.

Amongst the major metabolic triggers of β-cell dysfunction is glucose and lipid-induced cytotoxicity. In the context of obesity, elevated glucose and fatty acids increase insulin demand and contribute to β-cell oxidative stress. Additionally, excess free fatty acids accumulated in β-cells induce further ROS generation, contributing to ER stress and β-cell dysfunction. β-cell mitochondria therefore need to appropriately adapt to glucolipotoxic conditions to avoid progression towards overt T2D73. Changes in mitochondrial morphology have been previously associated with modified nutrient utilisation, with a strong correlation between mitochondrial fragmentation and increased lipid utilisation via fatty acid oxidation (FAO)74, a process inhibited in β-cells under high glucose conditions to favour metabolic coupling towards insulin secretion73,75 that could potentially be modulated by the GLP-1R under excess lipids to enable lipid clearance and detoxification73. In support of this hypothesis, our MS interactome indicates the association of active GLP-1R with a range of factors involved in lipid metabolism, including lipases and regulators of lipase transfer to lipid droplets such as Mest76 and Copb177, lipid metabolising enzymes including TMEM120A78, Acsl479, Fads180, Chp181, Cds282, and Apgat483, and mitochondrial FAO and ketone body enzymes (HADHA/B84, Bdh185), as well as the ER/lipid droplet small GTPase Rab1886, several subunits of the mitochondrial ATP synthase, the respiratory chain subunit SDHA, and the FAO-fuelled plasma membrane Na+/K+ pump87. Interestingly, a recent study has identified ERMCSs as required for lipid radical transfer from mitochondria to the ER to reduce mitochondrial oxidative stress88, which could represent an alternative mechanism for ERMCS-localised GLP-1R signalling to enhance β-cell survival under glucolipotoxic conditions. Overall, the control of lipid metabolism is a likely effect of GLP-1R signalling at ERMCSs worthy of further investigation, with the SPHKAP paralog AKAP11 already shown to play an important role in lipid metabolism in astrocytes89.

Beyond interaction with lipid enzymes, our MS interactome analysis indicates that the GLP-1R binds to ERMCS-localised Sarcoendoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase (SERCA) pump in the ER and voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 2 (VDAC2) in the OMM, both involved in calcium/ion transfer across ERMCSs90, suggesting a prominent role for the receptor in the control of intra-organelle ion homoeostasis, with important implications for the regulation of mitochondrial function, ER stress responses and insulin secretion91. Overall, these MS-identified interactions suggest that the effect of GLP-1R PKA signalling at ERMCS might extend well beyond the MICOS complex into a more comprehensive programme of ER, mitochondria and lipid metabolic pathway regulation.

In summary, this investigation has unveiled the existence of a newly characterised inter-organelle signalling hub in pancreatic β-cells which involves active endosomal GLP-1R localisation to ERMCSs via VAPB binding and engagement of the AKAP SPHKAP to enable ERMCS-restricted cAMP/PKA activity via the assembly of PKA-RIα biomolecular condensates, leading to PKA phosphorylation of the MICOS complex, enhanced mitochondrial remodelling and improved mitochondrial function, with important implications for the modulation of β-cell function and survival and the potential to serve as a mechanism for GLP-1R-induced mitochondrial adaptation during metabolic stress and excess nutrient exposure. Further studies to investigate this later possibility, including examination of the effect of GLP-1R in β-cell lipid metabolism and mitochondrial nutrient utilisation under normal and glucolipotoxic stress conditions are warranted, as well as the investigation of the in vivo role of SPHKAP in GLP-1R-dependent glucoregulation.

Methods

Cell culture

INS-1 832/3 rat insulinoma cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 at 11 mM D-glucose, supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM pyruvate, 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. INS-1 832/3 cells stably expressing SNAP/FLAG-tagged human GLP-1R (hGLP-1R) or human GIPR (hGIPR) were generated by transfection of pSNAP-GLP-1R or pSNAP-GIPR (Cisbio) into INS-1 832/3 cells lacking endogenous GLP-1R or GIPR expression (INS-1 832/3 GLP-1R or GIPR KO, a gift from Dr Jacqueline Naylor, AstraZeneca92), followed by G418 (1 mg/mL) selection. Mycoplasma testing was performed biannually. Cell culture reagents were obtained from Sigma or Thermo Fisher Scientific.

Peptides and fluorescent probes

Exendin-4, GLP-1 and GIP were purchased from Bachem, semaglutide was from Imperial College London Healthcare NHS Trust pharmacy, and tirzepatide was a gift from Sun Pharmaceuticals. Custom analogues (exendin-F1 and exendin-D3) were from WuXi AppTec, China, and danuglipron and orforglipron were purchased from MedChemExpress. SNAP-Surface fluorescent probes were from New England Biolabs and MitoTracker™ Red CMXRos and ER-Tracker Red were from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

GLP-1R β-cell interactome

INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cells were treated in 6-cm dishes with vehicle or 100 nM GLP-1RA (GLP-1, exendin-4, exendin-F1 or exendin-D3) for 5 minutes. Following stimulation, cells were washed in ice cold PBS and osmotically lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA) with 1% protease inhibitor (Roche) and 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich) at 4 °C. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 17,000 × g and 4 °C for 10 minutes, and supernatants added to 40 μL anti-FLAG M2 agarose beads (A2220, Sigma-Aldrich) for overnight rotating incubation at 4 °C to increase binding efficiency. Samples were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 30 seconds, and bead pellets washed 3× in 500 μL wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) before storage at −80 °C until further analysis. The number of biological replicates per condition was 4 for all conditions apart from GLP-1-stimulated samples, which included 3 replicates. Negative controls included INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R cell lysates incubated with empty Sepharose beads (Sigma–Aldrich) and INS-1 832/3 cell lysates (not expressing the tagged receptor) incubated with anti-FLAG M2 beads.

Beads were resuspended in 150 μL 1 M urea in 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0 with 1 mM DTT, followed by addition of 1.5 μg Trypsin gold (Promega) with overnight digestion at 37 °C. Supernatants were subsequently acidified with 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), followed by desalting using reversed-phase spin tips (Glygen Corp) and drying using vacuum centrifugation. Dried peptides were resuspended in 0.1% TFA and Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) performed in single replicate injections as previously described93 using an Ultimate 3000 nano-HPLC coupled to a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) via an EASY-Spray source. Peptides were loaded onto a trap column (Acclaim PepMap 100 C18, 100 μm × 2 cm) at 8 μL/minute in 2% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA. Peptides were eluted on-line to an analytical column (Acclaim Pepmap RSLC C18, 75 μm × 75 cm). A 90-minute stepped gradient separation was used with 4–25% acetonitrile 80%, formic acid 0.1% for 60 minutes, followed by 25–45% for 30 minutes. Eluted peptides were analysed by Q-Exactive operating in positive polarity and data-dependent acquisition mode. Ions for fragmentation were determined from an initial MS1 survey scan at 70,000 resolution (at m/z 200), followed by higher-energy collisional dissociation of the top 12 most abundant ions at a resolution of 17,500. MS1 and MS2 scan AGC targets were set to 3e6 and 5e4 for a maximum injection time of 50 and 75 mseconds, respectively. A survey scan range of 350–1800 m/z was used, with a normalised collision energy set to 27%, minimum AGC of 1e3, charge state exclusion enabled for unassigned and +1 ions and a dynamic exclusion of 45 seconds.

Data was processed using the MaxQuant software platform (v1.6.10.43), with database searches carried out by the in-built Andromeda search engine against the Swiss-Prot Rattus Norvegicus database (Downloaded—21st May 2022; entries: 8132) concatenated with the human GLP-1R protein sequence. A reverse decoy database approach was used at a 1% false discovery rate (FDR) for peptide spectrum matches and protein identifications. Search parameters included: maximum missed cleavages set to 2, variable modifications of methionine oxidation, protein N-terminal acetylation, asparagine deamidation and cyclisation of glutamine to pyroglutamate.

Label-free quantification (LFQ) was enabled with a minimum ratio count of 1. Proteins were filtered for those containing at least one unique peptide and identified in all biological replicates included per condition. For normalisation, proteins were ranked by fold change increase in abundance compared with control (vehicle-treated) immunoprecipitates. The resulting data was pre-processed by elimination of proteins that are non-specifically bound and residual background proteins, such as common contaminants and reverse database proteins. To further facilitate the selection of GLP-1R interactors, the following criteria were established; (i) identified at least twice from four runs; (ii) not nuclear proteins; and (iii) previously identified in pancreatic β-cells. Untargeted LFQ intensity values, normalised to hGLP-1R levels in each immunoprecipitated sample, were analysed by LFQ Analyst94 to identify differences in levels of individual protein-GLP-1R interactions between vehicle and GLP-1RA-treated conditions. Paired t-tests adjusted for multiple comparisons using Benjamin–Hochberg FDR correction and Perseus type imputations were used for statistical analysis. To generate novel information about the functional pathways represented by these potential GLP-1R interactors, we performed pathway enrichment analysis with the GLP-1R binding partners exhibiting changes between vehicle and exendin-4-stimulated conditions using gProfiler.

cDNA and siRNA transfection

INS-1 832/3 cells were transfected with relevant amounts of plasmid cDNA outlined in Supplementary Table 1, or siRNA outlined in Supplementary Table 2, using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) in media without antibiotics according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experiments were carried out 24–48 hours after plasmid cDNA, or 72 hours after siRNA transfection.

Isolation and culture of pancreatic islets

WT or GLP-1R KO mice (generated in house95) were humanely euthanised before inflating the pancreas through the common bile duct with RPMI-1640 medium containing 1 mg/mL collagenase (Nordmark Biochemicals). The pancreas was then dissected, incubated at 37 °C for 10 minutes, and digestion halted with cold RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS (F7524, Sigma–Aldrich) and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin solution (15070-063, Invitrogen). Mouse islets were subsequently washed, purified using a Histopaque gradient (Histopaque-1119 and Histopaque-1083, Sigma–Aldrich) and rested overnight at 37 °C in a 95% O2/5% CO2 incubator before performing experiments in mouse islet culture medium (RPMI-1640 with 11 mM D-glucose, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin).

Human islets were received from the isolation unit at the Centre Européen d’Etude du Diabète (CEED), Strasbourg, or from isolation centres ascribed to the Integrated Islet Distribution Program (IIDP), National Institute of Diabetes and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA, with all ethical approvals in place. Human islets were cultured on arrival in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine, 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution, 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B, and 5.5 mM glucose at 37 °C in a 95% O2/5% CO2 incubator. Donor characteristics are indicated in Supplementary Table 3.

Islet shRNA transduction

Mouse islets were transduced with Control or SPHKAP shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles (MISSION® shRNA, Target Clone ID TRCN0000088765 mouse SPHKAP, Sigma–Aldrich) at an MOI of 1 and cultured for 72 hours before experiments.

Co-immunoprecipitation

INS-1 832/3 cells previously transfected with the relevant plasmids, INS-1 832/3 SNAP/FLAG-hGLP-1R or SNAP/FLAG-hGIPR cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 1.2 × 106 cells per well and incubated overnight. Cells were treated in normal media at 37 °C with vehicle, 100 nM exendin-4 for 5 minutes or 100 nM GIP for the indicated times, washed once with ice cold PBS and lysed with 1 mL lysis buffer supplemented with 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma–Aldrich) on ice. A cross-linking step [2 mM 3,3′-Dithiodipropionic acid di(N-hydroxysuccinimide ester) (DSP, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 minutes at room temperature followed by quenching with 20 mM Tris HCl for 15 minutes and 3× PBS washes] was performed prior to cell lysis for the SPHKAP-EGFP co-immunoprecipitation experiments to preserve protein-protein interactions despite proteolytic cleavage of the full-length fusion protein during the IP process. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 10 minutes, and supernatants added to 40 μL anti-FLAG M2 Magnetic beads (Sigma–Aldrich), anti-HA Magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific), or ChromoTek GFP-Trap® Magnetic Particles (Proteintech), and incubated at 4 °C for 1 hour. Beads were then washed 3x in 500 μL wash buffer and proteins eluted with urea buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8; 5% w/v SDS, 8 M urea, 100 mM dithiothreitol, 0.02% w/v bromophenol blue) at 37 °C for 10 minutes before SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis.

SDS-PAGE and western blotting