Abstract

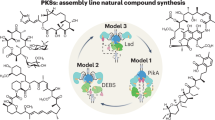

Modular polyketide synthases (PKSs) are multidomain, assembly line enzymes that biosynthesize complex antibiotics such as erythromycin and rapamycin. The modular characteristic of PKSs makes them an ideal platform for the custom production of designer polyketides by combinatorial biosynthesis. However, engineered hybrid PKS pathways often exhibit severe loss of enzyme activity, and a general principle for PKS reprogramming has not been established. Here we present a widely applicable strategy for designing hybrid PKSs. We reveal that two conserved motifs are robust cut sites to connect modules from different PKS pathways and demonstrate the custom production of polyketides with different starter units, extender units and variable reducing states. Furthermore, we expand the applicability of these cut sites to construct hybrid pathways involving cis-AT PKS, trans-AT PKS and even nonribosomal peptide synthetase. Collectively, our findings enable plug-and-play reprogramming of modular PKSs and facilitate the application of assembly line enzymes toward the bioproduction of designer molecules.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data supporting the results in this study are available in the paper and its Supplementary Information. The polyketide synthase enzyme sequences are from the MIBiG database (https://mibig.secondarymetabolites.org/) and NCBI database based on the BLAST search result. The PKS sources used for hybrid enzyme construction are given in Supplementary Table 1. Data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Grininger, M. Enzymology of assembly line synthesis by modular polyketide synthases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 401–415 (2023).

Khosla, C., Tang, Y., Chen, A. Y., Schnarr, N. A. & Cane, D. E. Structure and mechanism of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 195–221 (2007).

Menzella, H. G. et al. Combinatorial polyketide biosynthesis by de novo design and rearrangement of modular polyketide synthase genes. Nat. Biotechnol. 23, 1171–1176 (2005).

Menzella, H. G., Carney, J. R. & Santi, D. V. Rational design and assembly of synthetic trimodular polyketide synthases. Chem. Biol. 14, 143–151 (2007).

Yoon, Y. J. et al. Generation of multiple bioactive macrolides by hybrid modular polyketide synthases in Streptomyces venezuelae. Chem. Biol. 9, 203–214 (2002).

McDaniel, R. et al. Multiple genetic modifications of the erythromycin polyketide synthase to produce a library of novel ‘unnatural’ natural products. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1846–1851 (1999).

Weissman, K. J. Genetic engineering of modular PKSs: from combinatorial biosynthesis to synthetic biology. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 203–230 (2016).

Nava, A. A., Roberts, J., Haushalter, R. W., Wang, Z. & Keasling, J. D. Module-based polyketide synthase engineering for de novo polyketide biosynthesis. ACS Synth. Biol. 12, 3148–3155 (2023).

Klaus, M. & Grininger, M. Engineering strategies for rational polyketide synthase design. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35, 1070–1081 (2018).

Keatinge-Clay, A. T. The structures of type I polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 1050–1073 (2012).

Fischbach, M. A. & Walsh, C. T. Assembly-line enzymology for polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: logic, machinery, and mechanisms. Chem. Rev. 106, 3468–3496 (2006).

Donadio, S., Staver, M. J., McAlpine, J. B., Swanson, S. J. & Katz, L. Modular organization of genes required for complex polyketide biosynthesis. Science 252, 675–679 (1991).

Staunton, J. & Weissman, K. J. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 18, 380–416 (2001).

Zhang, L. et al. Characterization of giant modular PKSs provides insight into genetic mechanism for structural diversification of aminopolyol polyketides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 1740–1745 (2017).

Keatinge-Clay, A. T. Polyketide synthase modules redefined. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 4658–4660 (2017).

Peng, H., Ishida, K., Sugimoto, Y., Jenke-Kodama, H. & Hertweck, C. Emulating evolutionary processes to morph aureothin-type modular polyketide synthases and associated oxygenases. Nat. Commun. 10, 3918 (2019).

Su, L. et al. Engineering the stambomycin modular polyketide synthase yields 37-membered mini-stambomycins. Nat. Commun. 13, 515 (2022).

Miyazawa, T., Hirsch, M., Zhang, Z. & Keatinge-Clay, A. T. An in vitro platform for engineering and harnessing modular polyketide synthases. Nat. Commun. 11, 80 (2020).

Miyazawa, T., Fitzgerald, B. J. & Keatinge-Clay, A. T. Preparative production of an enantiomeric pair by engineered polyketide synthases. Chem. Commun. 57, 8762–8765 (2021).

Chemler, J. A. et al. Evolution of efficient modular polyketide synthases by homologous recombination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10603–10609 (2015).

Kudo, K. et al. In vitro Cas9-assisted editing of modular polyketide synthase genes to produce desired natural product derivatives. Nat. Commun. 11, 4022 (2020).

Ray, K. A. et al. Assessing and harnessing updated polyketide synthase modules through combinatorial engineering. Nat. Commun. 15, 6485 (2024).

Helfrich, E. J. & Piel, J. Biosynthesis of polyketides by trans-AT polyketide synthases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 231–316 (2016).

Englund, E. et al. Biosensor guided polyketide synthases engineering for optimization of domain exchange boundaries. Nat. Commun. 14, 4871 (2023).

Rittner, A. et al. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of fluorinated polyketides. Nat. Chem. 14, 1000–1006 (2022).

Bedford, D., Jacobsen, J. R., Luo, G., Cane, D. E. & Khosla, C. A functional chimeric modular polyketide synthase generated via domain replacement. Chem. Biol. 3, 827–831 (1996).

Tang, L., Fu, H., Betlach, M. C. & McDaniel, R. Elucidating the mechanism of chain termination switching in the picromycin/methymycin polyketide synthase. Chem. Biol. 6, 553–558 (1999).

Yuzawa, S. et al. Comprehensive in vitro analysis of acyltransferase domain exchanges in modular polyketide synthases and its application for short-chain ketone production. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 139–147 (2017).

Hagen, A. et al. Engineering a polyketide synthase for in vitro production of adipic acid. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 21–27 (2016).

Wlodek, A. et al. Diversity oriented biosynthesis via accelerated evolution of modular gene clusters. Nat. Commun. 8, 1206 (2017).

Thanapipatsiri, A. et al. Discovery of unusual biaryl polyketides by activation of a silent Streptomyces venezuelae biosynthetic gene cluster. ChemBioChem 17, 2189–2198 (2016).

Chen, S. et al. Organizational and mutational analysis of a complete FR-008/candicidin gene cluster encoding a structurally related polyene complex. Chem. Biol. 10, 1065–1076 (2003).

Banskota, A. H. et al. Isolation and identification of three new 5-alkenyl-3,3(2H)-furanones from two Streptomyces species using a genomic screening approach. J. Antibiot. 59, 168–176 (2006).

Caffrey, P., Bevitt, D. J., Staunton, J. & Leadlay, P. F. Identification of DEBS 1, DEBS 2 and DEBS 3, the multienzyme polypeptides of the erythromycin-producing polyketide synthase from Saccharopolyspora erythraea. FEBS Lett. 304, 225–228 (1992).

Schwecke, T. et al. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyketide immunosuppressant rapamycin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 7839–7843 (1995).

Villadsen, N. L. et al. Synthesis of ent-BE-43547A(1) reveals a potent hypoxia-selective anticancer agent and uncovers the biosynthetic origin of the APD-CLD natural products. Nat. Chem. 9, 264–272 (2017).

Lowry, B. et al. In vitro reconstitution and analysis of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16809–16812 (2013).

Ikeda, H., Kazuo, S. Y. & Omura, S. Genome mining of the Streptomyces avermitilis genome and development of genome-minimized hosts for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene clusters. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 41, 233–250 (2014).

Kellenberger, L. et al. A polylinker approach to reductive loop swaps in modular polyketide synthases. ChemBioChem 9, 2740–2749 (2008).

Zargar, A. et al. Chemoinformatic-guided engineering of polyketide synthases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 9896–9901 (2020).

Klaus, M., Buyachuihan, L. & Grininger, M. Ketosynthase domain constrains the design of polyketide synthases. ACS Chem. Biol. 15, 2422–2432 (2020).

Zhou, T. et al. Biosynthesis of akaeolide and lorneic acids and annotation of type I polyketide synthase gene clusters in the genome of Streptomyces sp. NPS554. Mar. Drugs 13, 581–596 (2015).

Ray, L. & Moore, B. S. Recent advances in the biosynthesis of unusual polyketide synthase substrates. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 150–161 (2016).

Seipke, R. F. et al. A single streptomyces symbiont makes multiple antifungals to support the fungus farming ant Acromyrmex octospinosus. PLoS ONE 6, e22028 (2011).

Yan, Y. et al. Multiplexing of combinatorial chemistry in antimycin biosynthesis: expansion of molecular diversity and utility. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12308–12312 (2013).

Hirsch, M. et al. Insights into modular polyketide synthase loops aided by repetitive sequences. Proteins 89, 1099–1110 (2021).

Yi, D. & Agarwal, V. Biosynthesis-guided discovery and engineering of α-pyrone natural products from type I polyketide synthases. ACS Chem. Biol. 18, 1060–1065 (2023).

Hansen, D. A., Koch, A. A. & Sherman, D. H. Identification of a thioesterase bottleneck in the pikromycin pathway through full-module processing of unnatural pentaketides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13450–13455 (2017).

Horsman, M. E., Hari, T. P. A. & Boddy, C. N. Polyketide synthase and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase thioesterase selectivity: logic gate or a victim of fate? Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 183–202 (2016).

Park, S., Hyun, H., Lee, J. S. & Cho, K. Identification of the phenalamide biosynthetic gene cluster in Myxococcus stipitatus DSM 14675. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26, 1636–1642 (2016).

Bozhüyük, K. A. J. et al. De novo design and engineering of non-ribosomal peptide synthetases. Nat. Chem. 10, 275–281 (2018).

Bozhüyük, K. A. J. et al. Evolution-inspired engineering of nonribosomal peptide synthases. Science 383, eadg4320 (2024).

Weber, T. et al. Molecular analysis of the kirromycin biosynthetic gene cluster revealed beta-alanine as precursor of the pyridone moiety. Chem. Biol. 15, 175–188 (2008).

Lohman, J. R. et al. Structural and evolutionary relationships of ‘AT-less’ type I polyketide synthase ketosynthases. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 12693–12698 (2015).

Klaus, M., D’Souza, A. D., Nivina, A., Khosla, C. & Grininger, M. Engineering of chimeric polyketide synthases using SYNZIP docking domains. ACS Chem. Biol. 14, 426–433 (2019).

Mabesoone, M. F. J. et al. Evolution-guided engineering of trans-acyltransferase polyketide synthases. Science 383, 1312–1317 (2024).

Buyachuihan, L., Stegemann, F. & Grininger, M. How acyl carrier proteins (ACPs) direct fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202312476 (2024).

Cogan, D. P. et al. Structural basis for intermodular communication in assembly-line polyketide biosynthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01709-y (2024).

Bagde, S. R., Mathews, I. I., Fromme, J. C. & Kim, C.-Y. Modular polyketide synthase contains two reaction chambers that operate asynchronously. Science 374, 723–729 (2021).

Drufva, E. E., Hix, E. G. & Bailey, C. B. Site directed mutagenesis as a precision tool to enable synthetic biology with engineered modular polyketide synthases. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 5, 62–80 (2020).

Kautsar, S. A. et al. MIBiG 2.0: a repository for biosynthetic gene clusters of known function. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D454–D458 (2020).

Tang, Y., Kim, C.-Y., Mathews, I. I., Cane, D. E. & Khosla, C. The 2.7-Å crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric fragment of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 11124–11129 (2006).

Xia, Y. et al. T5 exonuclease-dependent assembly offers a low-cost method for efficient cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, e15 (2018).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Hughes, A. J., Detelich, J. F. & Keatinge-Clay, A. T. Employing a polyketide synthase module and thioesterase in the semipreparative biocatalysis of diverse triketide pyrones. MedChemComm. 3, 956–959 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Kazuo for helpful discussion in hybrid PKS construction. We thank the Instrumentation and Service Center for Molecular Sciences at Westlake University for the assistance in MS and NMR analyses and the Westlake High-Performance Computing Center for providing computational resource. This research was supported by the ‘Pioneer’ and ‘Leading Goose’ R&D Program of Zhejiang (grant no. 2023SDXHDX0007), the National Natural Science Foundation of China General Program (grant no. 22177092) and Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory Construction Project to L.Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.H. performed all the biological experiments. Z.H., S.Y. and L.Z. performed the bioinformatic analyses. S.X., C.X. and R.-Z.L. performed the chemical synthesis. Z.H. and R.-Z.L. conducted the MS analyses. Z.H., S.X., S.Y. and L.Z. designed the experiments and analyzed the results. L.Z. conceived the research and wrote the paper with inputs from all coauthors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Z.H., S.Y., S.X., and L.Z. are co-inventors on a PCT patent application PCT/CN2024/142956 that incorporates discoveries described in this paper. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Biology thanks Constance Bailey, Martin Grininger and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Phylogenetic analysis of the KS domains from modular PKSs.

The first elongating KS domains in the first module of cis-AT PKSs (KS1, except for KSQ which does not catalyze condensation) were curated from MIBiG database and analyzed together with KSs from PKS-NRPS hybrids and trans-AT PKSs. Clade a, KS1 with KSQ-AT for starter unit loading. Clade b, KS1 with KSQ-AT for substrate loading and with downstream unnatural extender units-accepting AT. Clade c, KS1 with amino or guanidino group-containing starter units. Clade d, KS1 with ATL (starter unit-loading AT) for starter unit loading. Clade e, KS1 with aromatic or aliphatic rings as starter units. Clade f, KS1 with long-chain fatty acid or aromatic substrates activated by an adenylating domain. Clade g, KS1 with ATL domain inserted into module 1 forming the ACP-KS-ATL-AT-ACP type of module. Clade h, KS1 with pyrrole substrates. Clade i, KSs (not necessarily KS1) from trans-AT PKS-NRPS hybrids with peptide substrates. Clade j, KSs (not necessarily KS1) from cis-AT PKS-NRPS hybrids with peptide substrates. Clade k, KSs (not necessarily KS1) from trans-AT PKSs. The PKSs used in this study was marked in black dots. Detailed tree is provided in Supplementary Fig. S7. Sequence information was provided in the Supplementary Dataset.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Abbreviated biosynthetic pathways and the products of the 10 PKS/NRPS pathways used in this study other than the venemycin PKS.

The enzymes not used in this study are omitted for clarity. For the FscA, RakPKS1, E837PKS1, DEBS1, RapA, KirA1 and PteA1, the starter units and the extender units are shown on the corresponding ACP. For AkaPKS3, AntC, and PhePKS5, the polyketide intermediates being translocated to the downstream enzyme are shown on the corresponding ACP. The superscript 0 indicates inactive domains.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Steady-state kinetic analysis of hybrid PKSs.

The product formation of the engineered PKS pathways was measured under variable concentration of the first PKS with constant concentration of 0.2 μM vemH and 1 mM start unit. The dose-response curves of enzyme turnover velocity (μM product /min /μM VemH) were obtained from non-linear fitting of data to Michaelis-Menten equation. Error bars represent mean ± s.d. from three parallel reactions as technical replicates.

Extended Data Fig. 4 In vitro substrate specificity assay of VemH.

50 μL reaction mixture containing 10 mM ATP, 5 mM TCEP, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CoA, 1 mM N-acetylcysteamine thioester (SNAC) substrates SNAC1-SNAC6, 1.6 mM malonate, 1 μM MatB, 400 mM PBS (pH 7.5), 2 μM VemH were incubated at 30 °C overnight. a. Reaction scheme of VemH with SNAC5-6 and products 12a-b. b. HPLC analyses of VemH with SNAC5-6 monitored at UV 290 nm. c. Reaction scheme of VemH with SNAC1-4. VemH+SNAC1 produced the anticipated product 8b and the iteratively elongated 8a. VemH+SNAC2 produced the anticipated 9b and the iteratively elongated 9a. VemH+SNAC3 produced the iteratively elongated 8b. VemH+SNAC4 produced trace amount of the iteratively elongated 10a. d. LC-MS analysis of VemH with each substrate. Extracted ion chromatograms of m/z corresponding to the products were shown in red (8a), purple (8b), orange (9a), blue (9b), and green (10a), respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Biosynthetic schemes of PKSs with β-processing domains.

a. Proposed product formation mechanism by Rak-Vem-4 pathway. 2a can be produced by β-processing domain (DH-ER-KR) skipping; 2c can be produced by β-processing domain (DH-ER-KR) skipping and an iterative elongation at VemH; 2d was produced by fully functional β-processing domains and an iterative elongation of VemH. b. Proposed product formation mechanism by DEBS-Vem-4 pathway. 3a was produced by KR skipping; 3c was produced by fully functional domains. Iterative elongation during in vitro reaction of modular PKS has been documented previously66.

Extended Data Fig. 6 In vitro substrate specificity assay of AkaPKS4 and PheNRPS.

a. Reaction schemes of AkaPKS4 with synthetic N-acetylcysteamine thioester (SNAC) substrates and the product structures of compounds 8b-9b. b. LC-MS analysis of AkaPKS4 with each substrate. 50 μL reaction mixture containing 10 mM ATP, 5 mM TCEP, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CoA, 1 mM SNAC1-SNAC4, 1.6 mM malonate, 1 μM MatB, 400 mM PBS (pH 7.5), 2 μM AkaPKS4 were incubated at 30 °C overnight. Extracted ion chromatograms of m/z corresponding to the products were shown in purple (8b), orange (9a), blue (9b), respectively. c. Reaction schemes of PheNRPS with SNAC substrates and the product structures of compounds 11a–11d. d. LC-MS analysis of PheNRPS with each substrate. 50 μL reaction mixture containing 10 mM ATP, 5 mM TCEP, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM SNAC1-SNAC4, 1 mM alanine, 1 mM NADPH, 400 mM PBS (pH 7.5), 2 μM PheNRPS were incubated at 30 °C overnight. Extracted ion chromatograms of m/z corresponding to the products were shown in beige (11a), purple (11b), gray (11c), and blue (11d), respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Predicted structural models of hybrid PKSs.

a. Sequence alignment of the proteins used to construct hybrid PKSs with the position of cut sites 1–5 marked. AntC does not have KS-AT and only the ACP region is aligned. b. Predicted structures of the enzymes by AlphoFold2. KS domain (yellow), KS-LD-AT linker (cyan), AT domain (green), post-AT linker (magenta), ACP (gray). The extended post-AT linker of VemG is shown in white. The structure files are available at Supplementary Data.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phylogenetic analysis of KS-AT linkers from aminopolyol PKSs according to the upstream domain organization.

a. Phylogenetic tree of the KS-AT linkers. The tree was constructed by FastTree2.1.1 with branch support values, performed on Geneious Prime. Labels indicate sequence source and location in a PKS pathway. For example, ecoM2c indicates the KS-AT linker in the ECO-02301 pathway (eco) at the second PKS (2), third module (c) based on traditional module definition shown in panel b. eco: ECO-02301; med: mediomycin; tfb: tetrafibricin; nmd: neomediomycin; lin: linearmycin; cle: clethramycin; S.mel: Streptomyces melanospoorfaciens PKS; S.nbrc: Streptomyces. sp. NBRC 109436 PKS; S.RTd: Streptomyces. sp. RTd22 PKS; S.ven: S. venezuelae PKS S.mash: S. mashuensis PKS; K.med: Kitasatospora mediocidica PKS. Accession numbers for the PKSs are provided in Supplementary Information. b. The module duplication observed in PKS1s of aminopolyols, based on Zhang et al. 201714. Sequences with high similarity are colored with yellow (KR-containing module) and dark yellow (DH-KR-containing module) to illustrate module duplication. Types of KS-AT linkers from the PKS1s of each pathway are shown in circle, triangle, and box as explained in panel c. The clear separate clades were observed in the tree depending on the types of its upstream domains, suggesting that KS-AT linkers also comigrate with its upstream sequences during module duplication.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Phylogenetic analysis of KS-AT linkers from aminopolyol PKSs according to the types of the downstream AT.

Phylogenetic analysis of KS-AT linkers according to the types of the downstream AT. The data is identical to Extended Data Fig. 8 but differently labeled. The tree shows a clear separation of KS-AT linkers associated with downstream methylmalonyl-CoA specific AT (red star) and malonyl-CoA specific AT (blue circle), suggesting a conserved interaction between the linker and the downstream AT.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods for chemical synthesis, Table 1, Figs. 1–102 and references.

Supplementary Table 2

Lists of plasmids, primers, strains, proteins and reagents used in this study.

Supplementary Data 1

Source sequences of Supplementary Fig. 1 and statistical source data of Supplementary Fig. 3.

Supplementary Data 2

Structure files for Extended Data Fig. 7 in pdb format.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data of Fig. 1d.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data of Fig. 2b,d.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data of Fig. 3b,d,e.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Sequences used for tree building.

Source Data Extended Data Figs. 8 and 9

Sequences used for tree building.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Z., Xie, S., Liu, RZ. et al. Plug-and-play engineering of modular polyketide synthases. Nat Chem Biol 21, 1361–1367 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01878-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-025-01878-4

This article is cited by

-

Gene conversion-associated successive engineering of modular polyketide synthases

Communications Chemistry (2025)

-

Design principles imprinted by evolution

Nature Chemical Biology (2025)