Abstract

Music, a universal language and cultural cornerstone, continues to shape and enhance human expression and connection across diverse societies. This study introduces SpectroFusionNet, a comprehensive deep learning framework for the automated recognition of electric guitar playing techniques. The proposed approach first extracts various spectrograms, including Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT), and Gammatone spectrograms, to capture the intricate audio features. These spectrograms are then individually processed using lightweight models (MobileNetV2, InceptionV3, ResNet50) to extract discriminative features of different guitar sounds, with ResNet50 yielding better performance. To further enhance the classification performance across nine distinct guitar sound classes, two types of fusion strategies are adopted to provide rich feature representation: One is early fusion where the spectrograms are combined before the feature extraction and the other one is late fusion approach where the independent features from spectrograms are concatenated via three approaches: weighted averaging, max-voting and simple concatenation. Then, the fused features are subsequently fed into nine machine learning classifiers, including Support Vector Machine (SVM), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Logistic Regression, Random Forest etc., for final classification. Experimental results demonstrate that MFCC-Gammatone late fusion provided the best classification performance, achieving 99.12% accuracy, 100% precision, and 100% recall across 9 distinct guitar sound classes. To further assess the SpectroFusionNet’s generalization ability, real-time audio dataset is evaluated, demonstrating an accuracy of 70.9%, indicating its applicability in real world scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Music stands as an enduring cornerstone of human culture, serving as a universal language of expression that spans across time and place. From the earliest forms of vocalizations and simple instruments to complex compositions, music has woven itself into the fabric of society, entertaining, uniting, and enlightening communities worldwide1. The electric guitar has revolutionized music, particularly in rock, blues, and jazz genres, with its electrifying sound. Guitar playing encompasses a variety of techniques, each adding its unique flavor to the music. Techniques such as fingerpicking, strumming, hammer-ons, pull-offs, bending strings, slides, tapping, and palm muting contribute to the diverse palette of sounds and styles found in the world of guitar playing. In modern musical analysis, there’s a pressing need to go beyond mere pitch and onset detection. Particularly in guitar performances, nuances like pull-offs, hammer-ons, and bending techniques offer invaluable insights for both transcription accuracy and instructional purposes. By delving into these subtleties, novice players can grasp and master their craft better2.

In the realm of guitar transcription, various methods have been employed over time to capture the intricate details of guitar performances. Traditionally, manual transcription methods have prevailed, involving skilled musicians transcribing music by ear or visually observing performances. Tablature notation has been particularly instrumental, representing guitar music graphically by assigning numbers to indicate frets on each string3. Similarly, standard notation, although less effective in capturing nuances, has provided a standardized format for representing guitar music. Nonetheless, for solo guitar performances, detailed note-by-note transcription, including the playing techniques associated with each note, is crucial. The sequence of notes forms the melody, while techniques like bends and vibrato influence the guitar performance’s expression4. Accurate transcription of these elements is essential for capturing the full essence of a guitar performance. Manual transcription requires significant musical training and time investment. Although automated services are not flawless, they greatly simplify the process for music enthusiasts and novice guitar players. These tools facilitate understanding and enjoyment of music, contributing to its educational, recreational, and cultural value.

In recent years, advancements in technology have led to the development of modern techniques for guitar transcription that go beyond traditional methods. Automatic transcription software now utilizes sophisticated algorithms and machine learning models to analyse audio recordings and generate accurate transcriptions, including detailed playing techniques. Signal processing techniques, such as spectral analysis and feature extraction, help identify specific guitar techniques like hammer-ons, pull-offs, and string bends. Additionally, interactive learning platforms and apps use real-time audio recognition to provide instant feedback on playing accuracy and technique. These systems adapt in real-time, incorporating user feedback to refine predictions dynamically5. With the growing demand for lightweight architectures in guitar transcription applications, pre-trained models have gained traction due to their computational efficiency and effectiveness in feature extraction from various spectrograms. Feature fusion, in particular, has emerged as a promising approach to combine complementary information from different spectrogram modalities, enhancing transcription accuracy. In our proposed work, spectrograms of audio files, specifically Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC), gammatone, and Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT), are processed through pre-trained models such as MobileNetV2, ResNet50 and InceptionV3.

In this work, we introduce SpectroFusionNet, a novel framework for electric guitar technique recognition, leveraging an innovative approach to spectrogram fusion. To the best of our knowledge, combining early and late fusion of spectrogram features has not been previously explored. By incorporating spectrogram types like Gammatone and CWT alongside MFCC, our framework captures unique audio features that enrich the representation of guitar sounds. We further enhance classification performance through advanced fusion strategies, utilizing both early and late fusion methods. Lightweight models are employed to achieve high classification accuracy while avoiding the need for computationally intensive architectures, with ResNet50 demonstrating optimal feature extraction capabilities. The proposed methodology is validated using real-world data under non-ideal recording conditions, outperforming current state-of-the-art approaches without relying on computationally expensive deep learning models. Thus, to summarize, the key contributions of proposed approach is as follows:

-

Pairwise Fusion Strategy: Unlike conventional ensemble methods, this paper proposes early and late fusion strategies for combining features extracted from different spectrogram types (MFCC, Gammatone, CWT). This novel combination allows the system to leverage complementary information from diverse spectrogram representations.

-

Late Fusion Optimization: Among late fusion techniques, this work explores max voting, weighted averaging, and concatenation, identifying max voting as the most effective. Such detailed analysis across multiple fusion strategies is limited in prior work.

-

Real-Time Testing Workflow: This work emphasizes the practical applicability of the system by validating it on real-time audio samples, tailored for real-time scenarios. This ensures that the proposed system is not only theoretical but also deployable in real-world applications.

Related works

Numerous methods have been explored for recognizing guitar playing techniques. For instance4, describes a two-stage framework for analyzing electric guitar solos without accompaniment. The first stage uses the MELODIA tool to identify melody contours, while the second stage detects playing techniques via a pre-trained classifier using timbre, MFCC, and pitch features. This method, tested on 42 guitar solos, achieved a best average F-score of 74% in two-fold cross-validation. Another approach in6 focuses on the automatic transcription of isolated polyphonic guitar recordings, extracting parameters like note onset, pitch, and playing styles. Using a robust partial tracking algorithm with plausibility filtering, it achieved high accuracy in several tasks: 98% for onset and offset detection, 98% for multipitch estimation, 82% for string number estimation, 93% for plucking style estimation, and 83% for expression style estimation. Additionally7, explores the classification of electric guitar playing techniques using features from the magnitude spectrum, cepstrum, and phase derivatives. Evaluating 6,580 clips and 11,928 notes, it found that sparse coding of logarithm cepstrum, group-delay function (GDF), and instantaneous frequency deviation (IFD) resulted in the highest average F-score of 71.7%.

Modern advancements have introduced deep learning solutions and architectures for guitar effect classification and parameter estimation. In8, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) were applied to classify and estimate parameters for 13 different guitar effects, including overdrive, distortion, and fuzz. A novel dataset was created, consisting of monophonic and polyphonic samples with discrete or continuous settings, totalling around 250 h of processed samples.

The study achieved over 80% classification accuracy, revealing similarities in timbre and circuit design among effects. Parameter estimation errors were generally below 0.05 for values ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. In another study9, CNNs were employed to generate guitar tabs from audio recordings using the constant-Q transform. This method accurately extracted chord sequences and notes from solo guitar recordings, achieving an 88.7% accuracy. The study introduced GUITARSET, a dataset with detailed annotations of acoustic guitar recordings, including string positions, chords, beats, and playing style in JAMS format.

Further, recent developments in signal processing have seen the emergence of pre-trained models for transfer learning, as demonstrated in10. It presents a comprehensive study comparing the performance of nine widely used pre-trained CNN models and a custom-designed CNN model for crop disease detection. The pre-trained models include EfficientNetB4, EfficientNetB3, InceptionResNetV2, Xception, DenseNet201, ResNet152, ResNet50, MobileNetV2, and VGG16. The results showed that the pre-trained models generally outperformed the custom CNN in terms of accuracy and F1-score, with models like EfficientNetB4, ResNet152, and Xception achieving exceptional results. In summary, various CNN frameworks have been proposed in the literature for guitar play recognition and some of them have been elaborated in Table 1.

Various approaches to feature fusion have also emerged, including early, late, and hybrid fusion techniques. In early fusion, as demonstrated in11, combining raw waveform signals and spectrograms via vector stitching enhances spoofed speech detection by improving classification accuracy while reducing model parameters. This method also emphasizes the importance of analysing high-frequency waveform components and harmonic features in spectrograms using SHAP analysis. Late fusion, as shown in12, applies a multi-modal framework using separate classifiers for different features (such as MFCC and spectrograms) before combining the results, achieving an 86.13% accuracy in depression detection. The model integrates MFCC features with a residual-based deep Spectro-CNN architecture, further refining the classification output. The hybrid approach, as detailed in13, employs both feature-level and decision-level fusion, integrating visible and infrared images with speech features, resulting in a robust automatic emotion recognition (AER) framework with an accuracy of 86.36%. The two-layer architecture combines the strength of different modalities, enabling light-invariant emotion detection in real-world environments.

Additionally, other methods for guitar play recognition have been explored, such as motion capture and note frequency recognition, as described in14. This approach combines finger motion capture with note frequency recognition to provide comprehensive feedback on a guitarist’s performance. After testing a number of classification methods for hand position classification, the random forest algorithm produced the best results, with an average classification accuracy of 97.5% for each finger and 99% accuracy for overall hand movement. For note recognition, the harmonic product spectrum (HPS) method achieved the highest accuracy at 95%. Another study15 introduces a multimodal dataset for recognizing electric guitar playing techniques. This dataset comprises 549 video samples in MP4 format and corresponding audio samples in WAV format, encompassing nine distinct electric guitar techniques. These samples were generated by a recruited guitarist using a smartphone device. This dataset forms the basis for the subsequent analysis in our research.

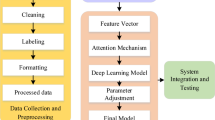

Methodology

Feature extraction using spectrogram analysis

Feature extraction is a crucial step in audio analysis, and spectrograms like Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients, Continuous Wavelet Transform, and Gammatone are specifically chosen for their ability to capture detailed and nuanced representations of audio signals16,17,18. Unlike prosodic or acoustic features, which may not fully encapsulate the intricacy and variability of musical performances, these spectrograms provide comprehensive time-frequency representations. This allows for a more precise analysis of the intricate timbral characteristics and playing techniques of the guitar, leading to enhanced accuracy and reliability in automated recognition systems.

MFCC

Mel Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC) spectrograms capture the power spectrum of audio signals by mimicking the human ear’s sensitivity to different frequencies, making them particularly effective for music analysis19,20. This attribute is especially suited for guitar play recognition, as it accurately represents the instrument’s timbral characteristics. MFCCs efficiently distinguish subtle nuances and patterns in guitar playing styles, and their robustness to noise and variations significantly enhances recognition performance. To extract MFCC from an audio signal \(\:x\left(t\right)\), the audio frames are converted into overlapping frames \(\:{x}_{n}\) followed by computing the Fourier transform to obtain the power spectrum for each frame. This spectrum is then passed through a series of Mel-scaled triangular filter banks, which map the frequencies f to the Mel scale \(\:{F}_{Mel}\), to better align with human auditory perception as described in Eq. (1).

Finally, Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) (represented in Eq. (2)) is applied to the log Mel-filtered values \(\:log\left(M\left[m\right]\right),\:\)to decorrelate and reduce dimensionality, producing a compact set of coefficients known as MFCCs.

where n indexes the cepstral coefficients, M is the number of Mel filters and \(\:M\left[m\right]\) is the Mel Spectrum.

CWT

Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT) spectrograms21 depict how audio signals evolve across different frequencies and time intervals, providing a detailed multi-resolution view essential for music analysis. This feature accurately captures the instrument’s varied timbral nuances and transient dynamics, crucial for distinguishing playing techniques and styles. CWT spectrograms excel in identifying subtle variations in pitch, timbre, and dynamics inherent to guitar performances, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of automated recognition systems in diverse audio contexts. In this study, we utilize the Morlet wavelet function for the CWT due to its effective time-frequency localization. The Morlet wavelet \(\:\phi\:\left(t\right)\) described in Eq. (3) is given as,

where \(\:{w}_{0}\) is the central frequency of the wavelet, (typically set to 6 in this work) for a balance between time and frequency resolution. The Continuous Wavelet Transform of an audio signal \(\:x\left(t\right)\) is computed as,

In Eq. (4), a represents the scale parameter, controlling the wavelet’s frequency, b represents translation factor, \(\:{\phi\:}^{*}\left(\frac{t-b}{a}\right)\) is the scaled Morlet transform, and \(\:\frac{1}{\sqrt{a}}\) is a normalization factor.

Gammatone

A Gammatone spectrogram analyses audio signal using a series of bandpass filters that mimic the human auditory system’s response, providing a representation of the signal’s frequency components22.

This approach is ideal as it closely mirrors the ear’s sensitivity to different frequencies and helps in accurately representing the instrument’s timbral characteristics. The Gammatone spectrogram’s ability to analyse signals in a manner akin to human perception enables it to distinguish subtle nuances in guitar playing styles. Gammatone filter bank is employed due to its effectiveness in capturing the intricate details of musical performances, enhancing the accuracy of automated recognition systems. The Gammatone filter in time domain \(\:g\left(t\right),\) is defined in Eq. (5).

where \(\:n\) is the filter order, \(\:b\) is the bandwidth of the filter, \(\:\varnothing\:\) denotes the phase and \(\:\:f\) represents the center frequency of the filter. Figure 1 shows the nine classes of guitar sounds and the corresponding spectrograms. From Fig. 1, it is understood that the spectrograms provide rich detailed information which will be very useful for analysing the key patterns of different guitar sounds.

Baseline model selection

Selecting an appropriate baseline model is crucial for developing an efficient and effective system for recognizing electric guitar playing techniques. The choice of baseline models impacts both the accuracy and the computational efficiency of the system, particularly when considering deployment in real-life applications where resources may be limited. These models were chosen for their balance of speed, accuracy, and efficiency, making them ideal for real-time music applications. Compared to heavier CNN models like VGG16, ImageNet and AlexNet, the chosen models (highlighted in Bold) have significantly fewer trainable parameters, which is illustrated in Table 2. This reduction in parameters not only decreases the computational cost but also enhances the feasibility of deploying these models in practical scenarios, such as mobile or embedded systems.

So, in this study, MobileNetV2, InceptionV3 and ResNet50 are selected as our baseline models due to their lightweight architecture and proven performance in various computer vision and audio analysis tasks.

MobileNetV2

MobileNetV223 is a lightweight and efficient CNN architecture specifically designed for mobile and embedded vision applications. It incorporates an inverted residual structure and linear bottlenecks, along with depth-wise separable convolutions, which together optimize both speed and accuracy (displayed in Fig. 2). As a result, this architecture is particularly well-suited for real-time processing of audio features extracted from guitar sounds. Let \(\:X\:\left(i,j,m\right)\) represents the input spectrogram in the \(\:m\)-th channel having pixel coordinates at \(\:\left(i,j\right)\:\)and\(\:{\:F}_{p}\left(m,n\right)\) denotes the \(\:1\times\:1\) point wise filter\(\:.\:\) Then, the output feature map \(\:{Y}_{p}\left(i,j,n\right)\)for the \(\:m\)-th channel by performing point-wise convolution is defined as,

Now, the depth wise convolution \(\:{Y}_{d}\left(i,j,m\right)\:\)which is another critical component is defined by Eq. (6).

where \(\:N\) denotes the size of the filter. In this paper, \(\:N\) is fixed to 3. To preserve the rich feature information with reduced information loss, inverted residual block with linear bottleneck is used. It is described by,

where \(\:T\) is the expansion factor, \(\:PW\) is pointwise convolution, and \(\:DS\) is depth-wise convolution Finally, the extracted features are mapped using the fully connected layer with the final class predictions as given in Eq. (8).

where \(\:C1\) is the initial convolution layer.

InceptionV3

InceptionV3 is a deep CNN architecture (shown in Fig. 3) notorious for its high performance and efficiency. It employs a combination of factorized convolutions and aggressive regularization to achieve high accuracy with fewer parameters24. InceptionV3 can be utilized to analyse and classify complex audio features extracted from guitar sounds. Its depth and architectural innovations allow it to capture intricate patterns in the audio data, making it well-suited for tasks such as recognizing chords, notes, and playing styles with high precision. Inception Module (\(\:IM\)), a core component of InceptionV3 architecture applies various convolution filters and pooling operations in parallel on the input spectrogram \(\:X\) to capture the information at multiple scales.

In Eq. (9), each branch applies different convolution operations (\(\:1\times\:1,\:3\times\:3,\:5\times\:5,\:etc.\)) and pooling operations. An Auxiliary Classifier, used to improve training with an auxiliary loss is given in Eq. (10).

where \(\:GAP\) is global average pooling, and \(\:FC\) is the fully connected layer. Finally, the overall architecture of InceptionV3, integrating multiple Inception modules, is described in Eq. (11).

This design makes InceptionV3 a valuable tool for precise, real-time music analysis and interactive applications.

ResNet50

ResNet50, a deep CNN model shown in Fig. 4 applies the concept of residual learning to mitigate the effect of vanishing gradient problem25. To enhance the feature extraction capability, this model stacks 50 layers with the residual blocks to learn residual mappings. Each residual block (\(\:RB\)) consists of convolution layers (\(\:1\times\:1,\:3\times\:3)\) and shortcut connections to extract the deeper details at various scales. The final classification output \(\:ResNet50\left(X\right)\:\)is described by,

where \(\:GAP\) is global average pooling reduces the feature dimensions and \(\:FC\) is the fully connected layer used in combination with \(\:Softmax\) for final classification.

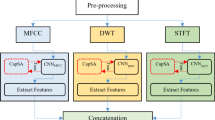

Proposed spectrofusionnet

The flow diagram of the SpectroFusionNet is shown in Fig. 5. Firstly, the raw audio signal \(\:x\left(t\right)\) is processed to obtain different type of spectrograms-MFCC, Continuous Wavelet Transform (CWT), and Gammatone which serves as input to the CNN models.

Let the spectrograms be denoted as \(\:{S}_{M},{S}_{C},\:{S}_{G}.\:\)Now, two types of fusion strategies are introduced, one is Early fusion \(\:{F}_{early}\) and the other one is late fusion \(\:{F}_{late}.\:\:\)In the first approach, the spectrograms are initially pairwise combined {\(\:{S}_{M}+{S}_{C},{S}_{C}+{S}_{G},\:{S}_{G}+{S}_{M}\}\) to produce a fused spectrogram \(\:{S}_{fused,p}\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}\text{e}\:p\in\:\left\{\text{1,2},3\right\}\) represents the three pairwise combinations. Each pair of spectrograms \(\:{S}_{fused,p}\) is processed through lightweight models \(\:{M}_{j}\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}\text{e}\:j\in\:\){MobileNetV2, InceptionV3, ResNet50} to obtain the feature vectors as described in Eq. (13).

For each model, three sets of fused vectors will be obtained. Now, the feature vectors \(\:{F}_{early,p\:}\)are passed to various machine learning classifiers \(\:{C}_{k},\:\text{w}\text{h}\text{e}\text{r}\text{e}\:k\:\)is one of the classifiers (as described in Sect. 3.3) for final classification of guitar sounds.

In the late fusion approach, initially the feature vectors \(\:{F}_{j,M},{F}_{j,C},\:{F}_{j,G}\) of each spectrogram \(\:{S}_{M},{S}_{C},\:{S}_{G}\) is obtained and then the features are fused via three strategies, Weighted Averaging, Max-voting and Simple concatenation26. These strategies are described in Eq. (15)-Eq. (17).

Equation (15) linearly combines each spectrogram with predefined weights while ensuring the sum of weights is equal to 1 (\(\:\sum\:{w}_{i}=1).\) To extract the dominant features, the maximum value from corresponding dimensions of each feature vector across the spectrograms is selected via the maximum voting strategy. It is given as,

In order to create a comprehensive feature vector, the third fusion strategy (as given in Eq. (17)) simply concatenates the features of all spectrograms before the final classification.

Once the fused features are obtained, these features are subsequently fed into machine learning classifiers for classification of guitar play sounds.

ML classifiers

For classifying guitar playing techniques, this paper employs a diverse set of machine learning classifiers, each with unique strengths27,28,29. Random Forest leverages an ensemble of decision trees to improve prediction accuracy and control overfitting by averaging multiple trees. Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Linear SVM are powerful for their ability to find the optimal hyperplane in high-dimensional space for classification. k-Nearest Neighbours (k-NN) is a straightforward algorithm that classifies samples based on the majority vote of their k-nearest neighbours, making it intuitive for multi-class classification. Logistic Regression models the probability of a discrete outcome and is particularly effective for binary and multi-class classification problems. Naive Bayes applies Bayes theorem with robust independence assumptions between features, often used for its simplicity and efficiency. Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP), a type of artificial neural network, excels in learning intricate patterns through its layered architecture. Logistic Model Trees (LMT) combine logistic regression and decision trees to capture both linear and non-linear patterns. Decision Tree classifiers provide a tree-like model for decision making by dividing the data into subsets according to feature values.

Gradient Booster builds an ensemble of weak learners, typically decision trees, to optimize performance by minimizing loss in a sequential manner. AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting) improves accuracy by focusing on misclassified instances, adjusting the weights iteratively to create a strong classifier from weak learners. This combination of classifiers allows for robust and flexible analysis, capturing both linear and complex relationships in the feature space for accurate recognition of guitar techniques. To ensure optimal performance for each classifier, extensive hyperparameter tuning was conducted. Hyperparameter tuning is crucial as it involves selecting the set of parameters that provides the best model performance on the validation set. For this purpose, a grid search strategy was employed, where a predefined set of hyperparameters was systematically evaluated to identify the combination that maximizes model performance. The comprehensive set of hyperparameters trained and tested for each classifier can be found in Table 3, which details the possible settings and best settings, along with their corresponding values for each hyperparameter.

Experiments

About the dataset

This study was conducted on a guitar style dataset, which contains 549 audio files across 9 different classes such as Alternate Picking, Bend, Hammer-on, Legato, Pull-off, Slide, Sweep Picking, Tapping, and Vibrato. These classes were carefully curated to ensure diversity in terms of playing styles, guitar tones, and recording conditions, making the dataset closely aligned with real-world guitar performances. The split ratio used in this work is 80% for training and 20% for testing. The class-wise split ratio for the guitar sounds is detailed in Table 4. All models of SpectroFusionNet were trained on Google Colab using the PyTorch and Tensorflow library. The Google Colab specifications adopted here include a 16GB Tesla T4 GPU and 16GB of high RAM.

Performance evaluation

To investigate the performance of the proposed work, the following objective metrics such as precision, recall/sensitivity, F1-score and Accuracy were considered30. The supporting equations for the above metrics are given in Eq. (18) - Eq. (21). Let us assume \(\:\alpha\:\) denotes the number of true positive samples, \(\:\beta\:\) denotes the number of true negative samples, \(\:\gamma\:\:\)denotes the number of false positive samples and \(\:\delta\:\) denotes the number of false negative samples. To understand the number of misclassifications predicted by the model, precision (\(\:P\)) measure the ratio of precisely predicted positive samples out of all predictions made for the positive class. It is given by,

Recall (\(\:R\)) measures the correctly identified true positive samples out of the total samples available for that class. It is described as,

F1-score is another statistical metric that combines precision and recall. This metric will be particularly useful when there is a class imbalanced dataset. It is defined in Eq. (20) as,

Finally, Accuracy (\(\:A\)) measures the proportion of true samples out of total number of samples available.

Simulation results and discussions

In the first phase of the proposed work, the spectrograms are individually processed by lightweight models and then classified using various machine learning classifiers to analyze the contribution of spectrograms and deep learning models to guitar play recognition. Table 5 lists the accuracy scores for the above context. Based on Table 5, the following interpretations are made.

-

ResNet50 outperforms MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3 (values are highlighted in italics) for all spectrogram types.

-

Compared to CWT and Gammatone, MFCC achieves better accuracy scores.

-

Among the machine learning classifiers, LMT (highlighted in bold) performs better than the others.

To further analyze performance, a confusion matrix illustrating class-wise performance for different guitar sounds is shown in Fig. 6. From Fig. 6, it is evident that all three spectrograms provide comparable performance for the alternate picking and bend classes. For hammer-on and pull-off, MFCC performs best, while for legato and tapping, CWT shows superior performance. Finally, for vibrato and sweep picking, both MFCC and Gammatone demonstrate comparable effectiveness. These findings suggest that each spectrogram excels in recognizing specific guitar sound classes. If these spectrograms are integrated effectively, the class-wise performance can be enhanced, ultimately improving the overall recognition accuracy. Therefore, in the second phase of the proposed work, early spectrogram fusion and late spectrogram fusion strategies with ResNet50 model are employed.

Tables 6 and 7 details the accuracy scores and F1-scores of early fusion and late fusion strategies for pairwise spectrogram combinations. From Tables 6 and 7, it is evident that late fusion strategies outperform early fusion (highlighted in bold). Specifically, the pairwise combination of MFCC and Gammatone achieves the highest accuracy (highlighted in italics) across most classifiers. Furthermore, late fusion approaches using max voting and weighted averaging perform significantly better compared to the simple concatenation method.

Among the classifiers, Logistic Regression and Linear SVM consistently demonstrate superior performance. To further evaluate the effectiveness of individual classes for the \(\:S\_M+S\_G\) combination, \(\:P\), \(\:R\), and F1-score metrics are presented in Table 8. Table 8 clearly shows that late fusion using the max voting strategy achieves the highest objective scores in terms of precision, recall, and F1-score for all nine classes of guitar sounds. This demonstrates the excellent performance of the proposed SpectroFusionNet approach. To further validate these findings, K-fold cross-validation (K=5) is applied to the feature extraction and classification pipeline31. Table 9 presents the performance of the proposed late fusion approach across various ML classifiers using 5-fold cross-validation. The mean accuracy and mean F1-scores across the five folds are highlighted in italics, while the highest accuracy and F1-score of 98.79% (highlighted in bold) are achieved by both Logistic Regression and SVM classifiers using the max voting fusion strategy. Random Forest is another alternative that provides competitive results. On the other hand, Naïve Bayes and AdaBoost perform poorly, indicating that these classifiers struggle to handle the fused features effectively.

Real time testing

To evaluate the efficacy of proposed approach, real-time datasets were tested for all the classes of guitar sounds. For real-time testing, we used audio clips extracted from YouTube videos of guitar performances. The audio clips are pre-processed by adjusting their playback speed. For samples shorter than 10 s, we slowed them down to 0.5x speed, and for those longer than 10 s, we sped them up to 2x speed (without changing the natural characteristics of the audio) before testing them using our proposed method. The overall accuracy scores for all the classifiers with late fusion strategy is shown in Fig. 7. From Fig. 7, it is evident that the late fusion via max voting attains the highest accuracy score of 70. 9% with Linear SVM classifier and the second-best score of 65. 49% by LMT classifier for the \(\:S\_M+S\_G\) combination. To analyze class-wise performance, each class contained nine real-time samples, and the corresponding statistical scores are displayed in Table 10. The results from Table 10 illustrate that, certain classes, such as Bend, Sweep Picking, and Slide, exhibit high precision and F1-scores, confirming that the majority of the samples are correctly classified. However, other classes, including pull off and Vibrato, show lower F1-scores due to their overlapping spectral characteristics, leading to misclassification errors. This suggests that guitar techniques relying on temporal variations32 pose a greater challenge for the model.

Table 11 compares state-of-the-art methods with the proposed work. Publicly available datasets were simulated using the proposed method, and the results are displayed in Table 11. It is evident from Table 11 that the proposed study statistically outperforms existing approaches, implying that SpectroFusionNet is adaptable to any dataset of interest. Among the evaluated fusion strategies, max voting achieved the highest performance by retaining the most discriminative spectrograms features. Additionally, max voting mitigates individual model biases by leveraging multiple decision boundaries, effectively enhancing the robustness of the classification process.

Conclusion

In summary, this research focuses on developing a spectrogram-based fusion approach for a multiclass guitar play sound recognition system using a hybrid combination of deep learning and machine learning classifiers. When processing individual spectrograms, the ResNet50 model outperforms MobileNetV2 and InceptionV3, according to the experimental results. Additionally, different spectrograms perform better for specific classes; some classes are better recognized by one spectrogram, while others benefit from another. To address this, spectrograms are combined pairwise using early fusion and late fusion strategies. The results reveal that late fusion strategies significantly outperform early fusion, achieving evaluation scores of 100% across all nine classes. Additionally, the proposed method was validated on other datasets to evaluate its efficacy in recognizing guitar play sounds. Once again, the method demonstrated superior performance, highlighting its robustness and generalization capability. To further assess the proposed method’s applicability in real-time scenarios, audio files representing all nine classes were tested. The proposed system achieved an accuracy of 70.9%, demonstrating its potential for real-time applications. To further enhance the performance, future work can incorporate temporal modeling approaches like LSTMs or transformers to capture sequential dependencies. Additionally, adaptive fusion strategies tailored for challenging classes could further improve model robustness in real-world scenarios.

Data availability

The Guitar style dataset analysed in this study are available in https://zenodo.org/records/10075352.

References

Schäfer, T. & Peter, S. Städtler Christine and Huron David, the psychological functions of music listening. Front. Psychol., 4, (2013).

Xi, Q., Bittner, R. M., Pauwels, J., Ye, X. & Bello, J. P. GuitarSet: A Dataset for Guitar Transcription, International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference, (2018).

Benetos, E., Dixon, S., Giannoulis, D., Kirchhoff, H. & Klapuri, A. Automatic music transcription: challenges and future directions. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 41, 407–434 (2013).

Chen, Y. P. & Yang, Y. H. Li Su and Electric Guitar Playing Technique Detection in Real-World Recording Based on F0 Sequence Pattern Recognition, International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference, (2015).

Wu, Y. T., Chen, B. & Su, L. Multi-Instrument Automatic Music Transcription with Self-Attention-Based Instance Segmentation, IEEE/ACM Transactions on Audio, Speech, and Language Processing, vol. 28, pp. 2796–2809, (2020).

Kehling, C., Abeßer, J., Dittmar, C. & Schuller, G. Automatic Tablature Transcription of Electric Guitar Recordings by Estimation of Score- and Instrument-Related Parameters, International Conference on Digital Audio Effects, (2014).

Su, Li, L. F. Y. & Yang, Y. H. Sparse Cepstral, Phase Codes for Guitar Playing Technique Classification, International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference, (2014).

Marco Comunità, D., Stowell & Reiss, J. D. Guitar effects recognition and parameter Estimation with convolutional neural networks. J. Audio Eng. Soc. 69, 594–604 (2021).

Yogesh Jadhav, A., Patel, R. H., Jhaveri & Raut, R. Transfer learning for audio waveform to guitar chord spectrograms using the Convolution neural network. Mob. Inform. Syst., (2022).

Alam, T. S., Jowthi, C. B. & Pathak, A. Comparing pre-trained models for efficient leaf disease detection: a study on custom CNN. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 11 (12), 1–26 (2024).

Ning Yu, L., Chen, T., Leng, Z., Chen & Yi, X. An explainable deepfake of speech detection method with spectrograms and waveforms. J. Inform. Secur. Appl., 81, (2024).

Arnab Kumar Das and & Naskar, R. A deep learning model for depression detection based on MFCC and CNN generated spectrogram features. Biomed. Signal Process. Control, 90, (2024).

Siddiqui, M. F. H. & Javaid, A. Y. A multimodal facial emotion recognition framework through the fusion of speech with visible and infrared images. Multimodal Technol. Interact., 4, 3, (2020).

Walaa, H. et al. A novel approach for improving guitarists’ performance using motion capture and note frequency recognition, Applied Sciences, 13, 10, (2023).

Alexandros Mitsou, A., Petrogianni, E. A., Vakalaki, C., Nikou, T. & Giannakopoulos, T. Psallidas and A multimodal dataset for electric guitar playing technique recognition, Data in Brief, vol. 52, (2024).

Kumaran, U., Radha Rammohan, S., Nagarajan, S. M. & Prathik, A. Fusion of mel and Gammatone frequency cepstral coefficients for speech emotion recognition using deep C-RNN. Int. J. Speech Technol. 24, 303–314 (2021).

Laurent Navarro, G., Courbebaisse & Jourlin, M. Chapter Two - Logarithmic wavelets. Adv. Imaging Electron. Phys. 183, 41–98 (2014).

Arun Venkitaraman, A., Adiga & Seelamantula, C. S. Auditory-motivated Gammatone wavelet transform. Sig. Process. 94, 608–619 (2014).

Vincent Lostanlen, J., Andén & Lagrange, M. Extended playing techniques: The next milestone in musical instrument recognition, DLfM’18: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Digital Libraries for Musicology, pp. 1–10, (2018).

Mannem, K. R., Mengiste, E. & Hasan, S. Borja García de Soto and Rafael sacks, smart audio signal classification for tracking of construction tasks. Autom. Constr., 165, (2024).

Ali, A., Xinhua, W. & Razzaq, I. Optimizing acoustic signal processing for localization of precise pipeline leakage using acoustic signal decomposition and wavelet analysis. Digit. Signal Proc., 157, (2025).

Gupta, S. S., Hossain, S. & Kim, K. D. Recognize the surrounding: development and evaluation of convolutional deep networks using Gammatone spectrograms and Raw audio signals. Expert Syst. Appl., 200, (2022).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L. C. MobileNetV2: Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks, IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 4510–4520, 2018. (2018).

Szegedy, C., Vanhoucke, V., Ioffe, S., Shlens, J. & Wojna, Z. Rethinking the Inception Architecture for Computer Vision, IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 2818–2826, 2016. (2016).

Demmese, F. A., Shajarian, S. & Khorsandroo, S. Transfer learning with ResNet50 for malicious domains classification using image visualization, Discover Artificial Intelligence, vol. 4, no. 52, (2024).

Mohammed, A. & Kora, R. A comprehensive review on ensemble deep learning: opportunities and challenges. J. King Saud Univ. - Comput. Inform. Sci. 35 (2), 757–774 (2023).

Aishwarya, N., Kaur, K. & Seemakurthy, K. A computationally efficient speech emotion recognition system employing machine learning classifiers and ensemble learning. Int. J. Speech Technol. 27, 239–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10772-024-10095-8 (2024).

Balakrishnan, S. A., Sundarsingh, E. F., Ramalingam, V. S. & N, A. Conformal Microwave Sensor for Enhanced Driving Posture Monitoring and Thermal Comfort in Automotive Sector, in IEEE Journal of Electromagnetics, RF and Microwaves in Medicine and Biology, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 355–362, Dec. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/JERM.2024.3405185

Sheth, V., Tripathi, U. & Sharma, A. A comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for classification purpose. Procedia Comput. Sci. 215, 422–431 (2022).

Rajasekar, E., Chandra, H., Pears, N., Vairavasundaram, S. & Kotecha, K. Lung image quality assessment and diagnosis using generative autoencoders in unsupervised ensemble learning. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 102, 107268 (2025).

Mahesh, T. R., Geman, O., Margala, M. & Guduri, M. The stratified K-folds cross-validation and class-balancing methods with high-performance ensemble classifiers for breast cancer classification. Healthc. Analytics. 4, 100247 (2023).

Kumarappan, J., Rajasekar, E., Vairavasundaram, S., Kulkarni, A. & Ketan Kotecha, and Siamese graph convolutional Split-Attention network with NLP based social sentimental data for enhanced stock price predictions. J. Big Data. 11 (1), 154 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kanwaljeet and Aishwarya conceptualized the idea, Chandhana and Ganesh Kumar performed the simulation. Ganesh Kumar and Aishwarya wrote the main manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chellamani, G.K., N, A., C, C. et al. SpectroFusionNet a CNN approach utilizing spectrogram fusion for electric guitar play recognition. Sci Rep 15, 16842 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00287-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-00287-w