Abstract

This study presents a novel methodology that integrates piezoelectric actuation and sensing with regression models and neural networks for high-accuracy detection and localization of multiple delamination and crack defects in composite laminates. An eight-layer graphite/epoxy composite plate, instrumented with piezoelectric patches, is excited using random voltage stimuli, generating structural responses captured by sensors. The proposed framework employs six regression techniques and artificial neural networks, achieving localization accuracy with \(R^2\) values exceeding 99.6%. Additionally, combining five signal decomposition methods with four classifiers enables defect type identification with up to 98.26% accuracy. The methodology demonstrates exceptional precision in detecting previously unseen delamination and crack defects down to the lamina level, optimized through grid search cross-validation. A comparative analysis highlights that piezoelectric sensor voltage signals outperform acceleration signals for defect characterization. This integrated piezoelectric-regression/neural network framework establishes a robust foundation for non-destructive evaluation, offering significant potential for real-time structural health monitoring applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The remarkable mechanical and thermal properties of multi-layer composites have led to their increasing popularity across various industries, including construction, automotive, and aviation. Identifying and localizing structural defects in these composite materials can help prevent irreversible accidents and ease maintenance efforts. Therefore, it is essential to effectively detect, identify, and localize defects in composite structures to enhance accuracy and expedite the identification process1. Due to their outstanding mechanical and thermal characteristics, multi-layer composites are widely accepted in numerous sectors, particularly in automotive, construction, and aviation. Composite laminated plates are commonly utilized in contemporary aerospace structures2. The use of composite materials in passenger aircraft is evidently on the rise3. In the automotive industry, composite materials are gaining traction as traditional materials often prove to be too costly and inadequate4. Gheorghe et al.5 advocate for the use of composite materials in manufacturing doors and other components of the vehicle’s body structure.

Using a Laser Doppler Vibrometer with a mirror-tilting device, Jeon et al.6 were able to get the whole steady-state wavefield using a single, fixed frequency stimulation from a mounted piezoelectric transducer. The depiction of damaged areas is then accomplished by mapping procedures based on local wavenumber filtering. Several tests are conducted on composite structures with various forms of damage, such as debonding and delamination on composite plates, in order to illustrate the suggested methodologies. The findings show that the methods can quickly check a range of composite structural components and are very successful at locating damage. A damage diagnosis method based on a genetic algorithm-based finite element model update is presented by Ashory et al.7, who also offer an assessment method with increased sensitivity for quantitative parameter detection. In order to do this, a suitable objective function based on weighted strain energy has been created, which has the maximum degree of sensitivity when compared to the other damage detection techniques. It is shown that the accuracy of damage location and intensity identification is increased utilizing the suggested strategy.

Boyina et al.8 studied the nonlinear mechanical behavior of laminated composite structures through a numerical model grounded in damage mechanics. Their progressive damage analysis employs a numerical technique to model the accumulation of damage and the resulting failure behavior in composite structures under service loads. This model is capable of predicting the remaining strength and stiffness of laminates, regardless of their lay-up and geometry. The advanced progressive damage model uses stress-based Hashin-type criteria along with appropriate ply discount degradation rules. The proposed model encompasses stress analysis, failure analysis, and the degradation of material properties. This project involves a detailed examination of a quasi-isotropic elliptical hole specimen to develop a failure model. Ghazali et al.9 conducted an extensive study on identifying and localizing various defects in 16-layer laminated composite plate structures. Their model effectively predicted both the type and location of defects, including delamination and cracks. To induce excitation in the composite structure, a random force is applied, with displacement responses on the free side serving as input for machine learning algorithms. The input for regression and neural network methods is derived from collecting the time signal for the free side displacement of a clamped laminated composite plate with different combinations of delamination and crack damage positions. The goal is to use the regression approach to accurately predict the location and characteristics of unknown damages that the machine has not previously encountered. The difference between their work and the present article is the lack of use of piezoelectric patches and the use of a composite with 16 layers.

Yang et al.10 proposed a vibration-based technique for detecting damage in delaminated plate-like structures using the modal frequency surface (MFS). This baseline-free method relies solely on the modal frequencies of the damaged structures. The analysis indicates that the detectability of delamination is more significantly affected by its through-the-thickness position than by its size. As the delamination moves from the detection surface toward the central plane, there is a quasi-exponential decrease in the level of modal frequency deviation. The amplitude of the signals received from both healthy and damaged structures over time plays a critical role in defect detection. It’s important to consider sensitivity to noise, and techniques like denoising or digital filtering can help reduce noise, particularly when the changes in signals due to damage are subtle. Hosni et al.11 employed a combination of piezoelectric accelerometers and strain gauge sensors for damage detection in steel frames. A numerical study using finite element modeling confirmed the method’s accuracy across various damage scenarios, including the loosening of bolts and nuts that lead to cracks.

Oliver et al.12 focused on delamination damage, which is a significant factor in the failure of multilayer composites due to tension and interlayer shear. They proposed a method that utilizes artificial neural networks along with modal data obtained from finite element analysis to detect and identify such damage. Their results showed that they could accurately pinpoint real damage locations and estimate severity, even in the presence of high measurement noise, achieving an accuracy rate of up to 95%. Soni et al.13 presented a novel approach for detecting damage in urban structures by employing a long short-term memory (LSTM) network. This LSTM-based method surpassed one-dimensional convolutional neural networks in multi-class damage identification and localization based on structural vibration responses. Chaupal et al.14 implemented five different convolutional neural network models to differentiate between damaged and undamaged states in glass fiber composite sheets. They used microscopic examination and data augmentation techniques to provide input for models such as VGG-16, ResNet-101, NasNetMobile, MobileNet-V2, and DenseNet-201. The findings indicated that MobileNet-V2 was the most effective model in terms of accuracy, parameters, and computation time.

Khan et al.15 proposed a supervised machine learning framework aimed at classifying and predicting structural defects in smart composite sheets, focusing on issues like delamination (which accounted for 4.5% of the total area) and partial detachment of sensors. They explored a dynamic model for multilayer composites that included piezoelectric components, utilizing low-frequency structural vibration responses. The research examined four scenarios involving a healthy structure and 18 scenarios involving a damaged structure, all stimulated by random harmonic inputs from a piezoelectric actuator. Supervised machine learning methods, including linear discriminant analysis, achieved a remarkable 100% classification accuracy. However, to tackle the problem of overfitting, principal component analysis was employed, which reduced the accuracy in the transformed feature space to 95.9%, while still ensuring 100% predictive performance.

Khan et al.16 introduced a convolutional neural network (CNN) approach for assessing delamination defects in smart composite sheets, both globally and locally. By leveraging low-frequency structural vibration outputs along with short-time Fourier transform, their study achieved an impressive overall classification accuracy of 90.1%. This CNN-based method eliminated the need for the lengthy process of selecting distinctive features, enhancing both efficiency and adaptability. Yessouf et al.17 developed a model for detecting damage in bridges using vibration data while accounting for temperature variations. Their hierarchical model, which combined a CNN-LSTM configuration with a traditional CNN model, achieved field accuracies exceeding 98% and 99%. Although the CNN-LSTM configuration converged more quickly and provided better matching, it required double the training time compared to the conventional CNN model. The CNN-LSTM model surpassed traditional CNN models and other machine learning techniques in bridge damage detection, achieving \(R^2\) values of 99.0% and 99.6% for simulation and experimental datasets, respectively.

Nirandaisabieh et al.18 conducted a comparison of different machine learning algorithms aimed at predicting road pavement damage. The gradient boosting regression algorithm showed impressive results, with \(MAE=0.02\), \(RMSE=0.03\), and \(R^2=99\%\), which suggests it can predict pavement damage with high accuracy. In another study, Viotti et al.19 explored a comprehensive machine learning strategy for detecting damage (specifically delamination) in sandwich composite structures. They utilized modal data from finite element analysis to train models for both damage localization and sizing, proving to be effective across a wide variety of damage scenarios in both regression and classification methods.

Using supervised machine learning techniques, such as regression and classification, Ghazali et al.20 precisely locate and identify local thickness reduction defects in cantilever beams. Five different mode decomposition techniques are applied in signal processing to break down each signal into its intrinsic mode functions (IMFs). To predict where defects will be found, they assess the effectiveness of ten regression techniques and five classification techniques. According to their findings, multi-class classification accuracies of up to 99.55% can be achieved by combining particular feature extraction and dimensionality reduction techniques with classification methods. Regression analysis is used by Avarzamani et al.21 to detect damage in sandwich composite structures with a lattice core. This technique can locate and identify multiple cracks and delaminations, as well as concurrent defects in the structure. They train different machine learning models using acceleration responses under random forces that were acquired using the finite element method. Regression (LGBM), k-Nearest neighborhood, and decision tree regression (DTR) were the most effective functions, according to the results. The damage classification models achieved an accuracy rate of roughly 98.8% in correctly identifying the damage and its location in the composite structure.

Ji et al.22 introduced the spatial gradient, a unique damage indicator that reflects the interplay between the wavefield and delamination. In order to drastically cut down on measurement time, they created a neural network that could immediately reconstruct the spatial gradient using high-sparsity Lamb wavefield data acquired at a very low spatial sampling rate. Comparing the presented method to the prior state-of-the-art methodologies, the reconstruction accuracy increases significantly, rising from 70% to 92% in the single-damage scenario and from 14% to 72% in the multi-damage situation. Using the reconstructed spatial gradient field for damage imaging using spatial covariance analysis, the method shows its viability and generalizability across different damage sites. In order to enhance repair planning, maintenance, and performance, Azad et al.23 introduced an interpretable deep learning model for the SHM of composites that is based on an explainable vision transformer (X-ViT). Multiple health states of carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites have been used to validate the suggested methodology. Comparing the X-ViT model to other widely used techniques, the former demonstrated superior damage detection ability. Furthermore, by using the patch attention aggregation technique to anticipate each health state in composites, the X-ViT approach successfully highlighted the area of interest and emphasized their impact on the decision-making process.

The topic of identifying structural damages has received considerable attention in the studies mentioned earlier, resulting in the use of various machine learning techniques for accurate damage detection and localization. However, there remains a significant gap in tackling the specific challenges related to identifying the type of defect and accurately locating multiple defect types within structures at the same time. In this study, we aim to address these gaps by utilizing and comparing six regression and neural network methods: Random Forest Regression (RFR), Light Gradient Boosted Machine (LGBM), Bayesian Ridge Regression (BRR), Decision Tree Regressor (DTR), Feed Forward Neural Networks (FNN) and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) for precise localization.

To tackle defect type detection, we integrate five mode decomposition methods: Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD), Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD), Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise (CEEMDAN), Empirical Wavelet Transform (EWT), and Variational Mode Decomposition (VMD). Additionally, we employ four classification methods-Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest, and Logistic Regression-on a laminated composite plate that includes delamination and cracks.

Input data for regression and classification methods consist of voltage readings from the surface of the piezoelectric patch attached to the composite laminate plate, which are collected from various combinations of delamination and crack damage positions. To assess performance, four distinct metrics are used: coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)), mean absolute error (MAE), root mean squared error (RMSE) for regression methods, and accuracy for classification methods. In addition to identifying regression methods with the best \(R^2\), MAE, and RMSE, and finding the most accurate combination of mode decomposition and classification techniques, the main goals of the study include the intelligent identification and localization of local delamination and crack defects. Another objective is to utilize and compare regression and artificial neural network methods to accurately predict the location and type of new damages that the machine has not been trained on yet.

Summary of data extraction steps, data analysis methods, and results of the present study. The schematic is created in Abaqus/CAE 2022 (Dassault Systémes Simulia Corp., https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/) and refined using Inkscape 1.3).

The study shows through evaluation metrics that acceleration signals from accelerometer sensors perform less accurately and have a higher error rate in identifying and localizing defects compared to those from piezoelectric sensors. What makes this study unique is its innovative use of regression methods for detecting multiple types of damage and accurately locating them. Key contributions of this research include the ability to predict the precise locations of two types of unseen defects: cracks and delamination. It also compares the accuracy and efficiency of various regression methods in pinpointing defect locations using evaluation parameters. Additionally, it assesses the classification accuracy of defects to determine the best classification method for composite plates that exhibit both crack and delamination defects simultaneously. This integrated piezoelectric-machine learning approach is applicable to other composite materials for detecting delamination and crack defects.

Methodology

In this study, an 8-layer composite laminated structure is excited and sensed using piezoelectric patches, and its temporal data is used for defect identification and localization purposes using machine learning methods. A summary of the study is shown in Fig. 1

Mathematical modeling

This section discusses the development of a dynamic mathematical model that is electromechanically coupled for both intact and delaminated smart composite laminates. The models for the displacement and electric potential fields are founded on higher-order electric potential fields24 and an enhanced layerwise theory25. The governing equations of motion for these two fields are derived through variational principles and implemented using the finite element method.

Displacement field with delamination and crack

The displacement of a point with coordinates (x, y, z) in an N-layered laminated composite is represented by combining first-order shear deformation theory with layerwise functions as referenced in25,26.

Using the 4N constraint equations related to displacement and shear stress continuity conditions, the layerwise functions \(A_i^k(z), B_i^k(z), C_i^k(z), D_i^k(z), {\bar{E}}_i^k(z), \bar{F}_i^k(z)\) for \((i = 1,2)\) are defined based on the material and geometric properties of the N-layered laminate24. In the presence of transverse cracks in the \(x-y\) plane, the displacement of additional degrees of freedom can be represented by Eq. (4).

In this context, let \(s = 1,...,N_E^P\) represent the number of enriched nodes within the plane that are affected by internal cracks, while \(m = 1,...,{N_E}\) denotes the finite element nodes located on the plane. The enriched nodes at the crack tips are indicated by \(h = 1,...,N_E^Q\), and the enriched nodes at the transverse crack tips are represented by \(b = 1,...,{N^F}\). The nodal values for the in-plane finite element nodes, along with the additional freedoms introduced by the tips of the matrix cracks and the in-plane matrix cracks, are denoted as \({{\tilde{U}}_{\alpha \zeta km}}(t)\), \({{\bar{U}}_{\alpha \zeta ks}}(t)\), and \({{\hat{U}}_{\alpha \zeta khb}}(t)\), respectively. The standard function, enriched function, and crack tip are represented by the symbols \({\Psi _m},{\Lambda _s},{\Pi _h}\), respectively27.

Electric potential field

It is assumed that a cubic distribution of the electric potential filed along the thickness of piezoelectric patches will satisfy the charge conservation law and the surface boundary conditions of the applied voltages25. Equation (5) provides the higher-order potential field for the qth piezoelectric layer.

The electric potential and electric field at the mid-plane of the qth piezoelectric patch are represented by the symbols \(\phi _0^q\) and \(E_z^q\), respectively. The mid-plane position and thickness of the piezoelectric transducer are denoted by the terms \(z_0^q\) and \({h^q}\), respectively. The potential difference between the top and bottom electrodes of the piezoelectric patches is indicated by the symbol \({{\bar{\phi }} ^q}.\)

Finite element implementation

Equations (1–3) states that the variables \(u_1\) , \(u_2\),w, \({w_y}\), \({w_x}\), \({\phi _1}\), \({\phi _2}\) can be used to express the displacement field of a healthy laminated composite with N layers. On the other hand, the variables \(u_1\) , \(u_2\),w, \({w_y}\), \({w_x}\), \({\phi _1}\), \({\phi _2}\) , \({{\bar{u}}_1^j}\) , \({{\bar{u}}_2^j}\) , \({{\bar{w}}^j}\), \({{\bar{w}}_x}^j\) , \({{\bar{w}}_y}^j\) can be used to express the displacement field of a delaminated composite. Alternatively, the variables \(\phi _0^q,E_z^q\) can be used to express the higher order electric potential field of piezoelectric patches. The finite element method is utilized to implement the two fields of Eqs. (1–5) for a plate element with four nodes. While the out-of-plane structural unknowns (w,\({{\bar{w}}^j}\) ) are interpolated using the Hermite cubic interpolation function (\({H_{m}}\),\({H_{xm}}\),\({H_{ym}}\)), the in-plane structural unknowns (\(u_1\) , \(u_2\), \({\phi _1}\), \({\phi _2}\), \({{\bar{u}}_1^j}\) , \({{\bar{u}}_2^j}\) ) and electrical unknowns (\(\phi _0^q\),\(E_z^q\) ) are interpolated using the linear Lagrange interpolation function (Nm). The structural and electrical unknowns can thus be expressed in terms of nodal values and interpolation functions as

and

Equation of motion

The variational principles can be used to derive the governing equation of motion based on finite elements in the following way:

In the context of the mechanical and electrical fields, \(\delta {\pi _u}\) and \(\delta {\pi _\phi }\) represent their respective energy functionals. The mass density is denoted by the symbol \(\rho\), while the material damping constant is represented by \(\gamma\). The charge density and traction vector components are indicated by \(t_i\) and \(q_e\), respectively. The equations of motion are derived by substituting Eqs. (6–9) into Eqs. (10–11), with Eq. (12) presenting the results in matrix form.

where the terms \({d_u}\), \({d_\phi }\) stand for the displacement and electrical unknowns, respectively. The smart structure’s mass, damping, and stiffness matrices are denoted by the terms \(M_{uu}\) , \(C_{uu}\) , \(K_{uu}\) , \(K_{\phi \phi }\) , in that order. The stiffness matrices of the electromechanical coupling are indicated by \(K_{u\phi }\), \(K_{\phi u}\).

Analysis of composite plate with delamination and crack defects

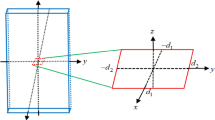

The structure discussed in this section features a multilayer plate composed of 8 composite layers, which are linked to two piezoelectric (PZT-5H) patches are located near the clamped end of the structure for both actuation and sensing purposes. The schematic representation of the structure is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Schematic of the laminated composite and two piezoelectric patches connected to the structure created in Abaqus/CAE 2022 (Dassault Systémes Simulia Corp., https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/) and refined using Inkscape 1.3).

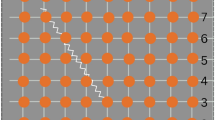

In order to simulate finite elements, Abaqus software (version 2022) has been used. The placement of the layers is 0–90 degrees as shown in the Fig. 3.

Schematic of 0-90 angle of placing the layers in the laminated composite created in Abaqus/CAE 2022 (Dassault Systémes Simulia Corp., https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/) and refined using Inkscape 1.3 (https://inkscape.org/).

The number of mesh elements used is 13227 quadrilateral meshes with 8 nodes. The schematic of the meshed structure is shown in the Fig.4.

Schematic of the mesh applied to the laminated composite created in Abaqus/CAE 2022 (Dassault Systémes Simulia Corp., https://www.3ds.com/products-services/simulia/products/abaqus/) and refined using Inkscape 1.3).

In order to check the convergence of the mesh, the first five natural frequencies of the structure have been used. Fig. 5 shows the convergence check results. As the mesh size decreases to 3.5 mm, the first five natural frequencies undergo very small changes of 1% or less, so from this mesh size the convergence process of the natural frequencies begins. However, for mesh sizes larger than 3.5 mm, the percentage of changes in natural frequencies with changing mesh size is greater than 1%. Therefore, this study adopts a mesh element size of 3.5 mm. To connect the layers of the composite plate and the piezoelectric patches to the composite plate, a tie connection is employed. The unbonded layer method28 has been utilized to model the delamination defect in the finite element approach.

In order to validate the finite element model used in this study, the first three natural frequencies of the cantilever 8-layer laminated composite plates expressed in 3 studies, including29,30,31, have been examined in Table 1.

According to the results mentioned in Table 1, the natural frequencies obtained in the present study are very close to the values of previous studies, indicating the high reliability of the finite element method used.

The structure is clamped on one side as part of the boundary condition. Figure 6 illustrates the dimensions of the various components of the structure and the locations of the defects. The sizes of all cracks and delaminations are specified in Fig. 6, While their position relative to the clamped side is considered variable to allow for different scenarios of occurrence of these two defects. It is worth noting that the thickness of the piezoelectric patches is assumed to be 1 mm and their position is assumed to be in the middle of the plate width.

To create a vibration data bank that includes time series data and to analyze the time domain responses of both healthy and damaged composites, we first modeled the composite plate structure along with the piezoelectric sensors attached to it using Abaqus software (version 2022). The voltage-time response from the piezoelectric sensor was recorded over a duration of 1 second, with a time increment of 0.001 seconds, resulting in 1001 data points for each time series. The data dimensions are \((405*1001)\), encompassing 404 damaged states, which include two types of cracks and delamination defects, as well as instances of only crack defects and only delamination defects, similar to the research conducted by Chaupal et al.14. Additionally, one state is designated as a healthy structure.

Piezoelectric elements are a promising choice for data collection from structures due to their ability to generate electric voltage in response to strain. They are cost-effective and eliminate the need for a shaker or accelerometer sensor for both stimulation and data acquisition. Initially, a piezoelectric actuator applies mechanical stimulation by introducing random voltage to its upper surface. This voltage creates strain in the piezoelectric structure, resulting in oscillating vibrations within the composite structure. The piezoelectric sensor then converts these vibrations into voltage signals, which reflect the vibration response of the structure.

To enhance the dataset for machine learning, 10 Gaussian white noise signals with signal-to-noise ratios of \(82 , \text {dB}, 84 , \text {dB}, 86 , \text {dB}, 88 , \text {dB}, 90 , \text {dB}, 92 , \text {dB}, 94 , \text {dB}, 96 , \text {dB}, 98 , \text {dB}, 100 , \text {dB}\) are added to the time signals. The application of Gaussian noise to improve machine learning datasets is supported by studies such as32 and33. As a result, with the addition of 10 Gaussian white noise signals to each original signal, the data dimensions expand to (4050*1001). A normalization method is employed to scale the features to a specified range, and this scaling transformation is then applied to the input data. The scaled features are stored in a new variable for use in machine learning methods. The normalization method is ‘Min Max Scaler’ and target range is [0,100].

To excite the piezoelectric (PZT-5H) structure, a band-limited Gaussian random white noise with frequency content of 0–400 Hz and sampling frequency of 1000 Hz was used due to the focus of the study on low-frequency vibrations of the composite plate. The actuator and sensor do not experience coupling interference because the excitation takes place at a frequency (0–400 Hz), which is less sensitive to the sensor, and the piezoelectric patch’s thickness is 1 mm, meaning that its resonant frequency range is around 1–10 MHz. The voltage waveform and power spectrum density shown in Fig. 7. It is important to note that the same random signal was applied to both healthy and defective states to effectively reveal the effects of different defects at various positions comparatively.

The mechanical properties of a single lamina of the composite laminate and piezoelectric properties are detailed in Tables 2 and 3.

For easy identification of various defects in the structure, a six-digit code is used to represent different states. The first two digits indicate the position of the delamination defect, the next two digits specify the delamination layer position, and the final two digits denote the crack fault position. For example, the code 23-05-18 indicates a delamination defect located 23 cm from the clamped side, with a delamination layer at 5, and a crack defect 18 cm from the clamped side, as shown in Fig. 6. Another example, the code 25-02-00, represents a delamination defect at 25 cm with a delamination layer at 2 and no crack. Additionally, the code 00-00-17.5 signifies no delamination defect, with only a crack defect present at a distance of 17.5 cm.

The voltage detected by the piezoelectric sensor is also random, as illustrated along with its power spectrum density in Fig. 8. Since the first and third mode shapes are aligned solely with the direction of the piezoelectric patch excitation, peaks are only observed around these two frequencies in Fig. 8b, while other modes remain unexcited. The Fig. 8b primary objective is to precisely illustrate the existence of variations in PSD diagrams (differences in amplitude and frequency at the peak points) of various flaws, which result from variations in the position, layer, and severity of the faults.

To illustrate how the position of defects affects the natural frequencies of the plate, Table 4, obtained using simulation in Abaqus, is provided. It is worth noting that modes 1, 3, and 5 are bending, but modes 2 and 4 are torsional. Table 4 shows that as the distance of the delamination from the clamped side increases, the first, second, and fifth natural frequencies also rise. Similarly, when the crack is positioned farther from the clamped side, the first and second natural frequencies increase as well. Notably, the impact of the crack defect on the increase of natural frequencies is more significant than that of the delamination defect. Furthermore, when both crack and delamination defects are present, having the crack closer to the free side and the delamination nearer to the clamped side results in higher first, second, and fifth natural frequencies compared to scenarios where the delamination is close to the free side and the crack is near the clamped side. However, this trend is reversed for the third and fourth natural frequencies.

In order to investigate the effect of crack length on the natural frequencies of the structure, we analyzed three crack lengths, 0.5 cm (10% of beam width), 1.5 cm (30%), and 3 cm (60%) and presented the results in Table 5. As expected, increasing crack length results in decreased natural frequencies due to reduced structural stiffness.

Machine learning methods

GridsearchCV

In this research, various machine learning models have been applied to the training dataset, raising the question of whether the parameter values chosen for each method yield the best results. This is where Grid search cross-validation becomes essential. The aim is to enhance the model’s accuracy and efficiency in every possible way. The hyperparameters of these models are crucial to their performance; selecting the right values can lead to significant improvements. By using parameters that demonstrated better cross-validation performance, a new model was automatically fitted to the entire training dataset. This approach aids in achieving a more precise estimation of performance. In this method, part of the data is utilized in K-fold cross-validation to evaluate the model, while another part is used for fitting. The prediction error is then estimated from Eq. (13) using cross-validation as follows:

where k is the number of subsets, n is the dataset size, T is the loss function, and \({{f^{-k(i)}}}\) is the fitting function36. The grid search cross-validation method used in this study for model training and meta-parameter selection is shown in Fig. 9.

Tuning meta-parameters using five-category cross-validation36.

Regression methods

Regression is a statistical technique that identifies patterns in the relationship between a set of independent factors and a dependent variable. This method allows for the correlation of a dependent variable with one or more independent (explanatory) variables. The process involves selecting the best-fitting line, fitting the data to it, and observing its dispersion. The two main types of regression are multiple linear regression and simple linear regression. Multiple linear regression uses two or more independent variables to predict or explain the outcome of the dependent variable. In this study, the three independent variables used for prediction in the composite plate structure are the crack position, the delamination position, and the layer location of delamination occurrence37.

Decision tree regressor

Selective Regression Analysis is a widely used regression technique that employs a categorization strategy for data sets. The main components of decision trees are leaf, branch, and root functions. One of the most straightforward ways to understand the relationship between variables and identify the most significant one is through the decision tree model, which is easy to interpret and visualize. The decision tree divides nodes into subnodes based on all variables, choosing the split that creates the most uniform subnodes. At the end of each path, the leaf provides the prediction result of the tree. To determine the best combination of effective parameters for the performance of the DTR method, the GridSearchCV function from scikit-learn (version 1.6.1) has been utilized. After applying the GridSearchCV method, the optimal values for the parameters included \(\max \_depth\) (the maximum depth of the tree) = [None, 10, 20, 30], \(min \_samples \_leaf\) (the minimum number of samples required at a leaf node) = [1, 2, 4], and \(min \_samples \_split\) (the minimum number of samples needed to split an internal node) = [2, 5, 10], resulting in values of 20, 1, and 2, respectively.

Random forest regressor

Machine learning techniques such as Random Forest Regressors (RFRs) are employed to tackle both regression and classification problems. They can be trained quickly using test data and help prevent overfitting38. RFRs consist of two main parameters: the number of variables used to build each tree and the total number of trees in the forest. They were developed to address limitations found in traditional decision tree methods. RFRs aim to reduce overfitting and enhance the speed of performance predictions38. The Random Forest algorithm utilizes bootstrapping and bagging to divide the training dataset into smaller subsets for training; it selects the optimal split rather than considering every variable. In this study, the RFR prediction method involved several steps: selecting a bootstrap sample from the training dataset, constructing a tree, and determining the best split from the subset for each bootstrap sample. By repeating the first two processes, multiple trees will be generated. The procedure for creating a Random Forest includes: for b trees in the forest, each tree receives a bootstrap sample of size n from the training set (row subsampling); m predictors are randomly chosen as candidates for splitting from p predictors in the training set (column subsampling); then, the best variable and split point are selected from the m predictors, dividing each node into two sub-nodes; finally, new data is forecasted by averaging the predictions from each tree. A structure Fig. 10 displays diagrams from the RFR model used in this investigation. In order to find the best combination of effective parameters in the performance of the RFR method, GridSearchCV36 function from scikit-learn (version 1.6.1) has been used, so after using the GridSearchCV method, parameters included \(max\_depth\)(The maximum depth of the tree):[None, 10, 20], \(n \_estimators\)(The number of trees in the forest):[100, 150, 200] , \(min \_samples \_split\)(The minimum number of samples required to split an internal node):[1,2,3] , \(min \_samples \_leaf\)(The minimum number of samples required to be at a leaf node):[1,2,3] have optimum values of None, 100 , 2 ,1 respectively.

Light gradient boosted machine regressor

The LGBM is a gradient boosting framework that employs a tree-based learning algorithm and a leaf-wise approach to build trees vertically39. Before creating the LGBM dataset, categorical features are converted to integer types. LGBM then calculates the split value for these categorical features using a distinctive method. Thanks to the robust capabilities of LGBM, it is now possible to predict quantiles. The loss function, known as quantile loss or pinball loss, is what sets quantile regression apart from general regression. This article includes equations from Eqs. (14–15) and provides a clear explanation of pinball loss. To identify the optimal combination of effective parameters for the performance of the LGBM method, the GridSearchCV36 function from scikit-learn (version 1.6.1) has been utilized. So after using the GridSearchCV method, \(learning \_rate\)(Learning rate shrinks the contribution of each tree)= [0.01, 0.05, 0.1],\(max \_depth\)(Maximum depth of the individual regression estimators)=[2, 5, 10],\(num \_leaves\) (number of leaves in full tree)=[50, 100, 150], \(n \_estimators\)(The number of boosting stages to perform)=[100, 150, 200] , \(boosting \_type\)([’gbdt’, ’dart’, ’goss’, ’rf’] ) have optimum values of 0.1 , 10 , 200 ,100 , goss respectively.

where z is the expected value, y is the actual value, and \(\tau\) is the intended quantile.

Bayesian ridge regressor

The Bayesian ridge technique is employed to estimate a probabilistic model for the regression problem, incorporating regularization parameters. The goal is to determine \({y_k}\) based on observations. The training sequence is denoted as \(({x_i},{y_i}), i = 1,...,m\), and during the initial k-fold split, \(({x_j}\) of length k is utilized as the test fold. In practical applications, given the training sequence \(({x_i},{y_i})\), where \(i = 1,...,n - 1\), the aim is to accurately predict \({y_n}\) for \({x_n}\). According to the model, the number of objects and labels, represented by \(({x_i},{y_i})\), is established by the rule40.

The distribution of \(\omega\) is represented as a random vector with a Gaussian parameterization characterized by its mean, covariance matrix, and \(N(0,({\sigma ^2}/a)I)\); meanwhile, the distribution of \(\beta\) follows a \(N(0,{\sigma ^2})\) pattern. Equation (17) provides the conditional distribution of the test label for the test object \({x_n}.\)

This is \({g_n}: = {x_n}^\prime {(X'X + aI)^{ - 1}}{x_n}\), where X is the design matrix of the training sequence. At this point, the Bayesian prediction range is:

In order to find the best combination of effective parameters in the performance of the BRR method, GridSearchCV36 function has been used, so after using the GridSearchCV method, \(compute \_score\)(compute the log marginal likelihood at each iteration of the optimization) , \(fit \_intercept\)(Whether to calculate the intercept for this model) , Maximum number of iterations:[True, False] , tol(Stop the algorithm if w has converged):[True, False] have optimum values of True , True, 200 , 0.0001 respectively.

Artificial neural networks

A neural network is made up of many neurons, which are basic processing units. Generally speaking, an artificial neural network (ANN) is a mathematical model or system made up of several parallel nonlinear artificial neurons that can be constructed as a single layer or several layers. Most ANNs consist of three layers: input, output, and hidden layers41. The literature has documented a wide variety of additional artificial neural network (ANN) types, including generalized regression neural networks (GRNNs), feed forward neural networks (FFNNs), and regression basis neural networks (RBNNs).

Feed forward neural networks (FNN)

The input, output, and hidden layers make up the FFNN’s minimum number of layers. Figure 11 displays the schematic diagram for an FFNN. After receiving weighted inputs from a layer below, neurons in the layer above exchange outputs with one another. Equation (19) calculates the sum of the weighted input signals, and Eq. (20) transfers this accumulation to produce a nonlinear activation function. Equation (21) is used to estimate the network error by comparing the network results with the actual observation findings42. Training is repeated until the error is within acceptable limits.

Neuron input is represented by \({X_i}\), weight coefficient by \({w_i}\), bias by \({w_0}\), error between observed value and network response by \({J_r}\), and neuron i’s observed value by \({O_i}\).Neuron i’s response is \({Y_i}.\)

Furthermore, N (number of input variables) in Fig. 11 is equal to 1001, M (number of hidden neurons in the hidden layer) is equal to 100, and 3 (number of output layers) is indicated. In order to find the best combination of effective parameters in the performance of the ANN method, GridSearchCV36 function has been used, so after using the GridSearchCV method, parameters \(learning \_rate\):[0.001, 0.01, 0.1] , \(model \_units\)(representing how many neurons in a particular layer):[(50, 50), (100, 100), (50, 100)] , \(model \_epochs\):[50, 100, 150] (the entire cycle of the algorithm’s interaction with the training data as it processes)have optimum values of 0.001 ,(100, 100) , 150 respectively.

Multilayer perceptron (MLP)

A feedforward neural network for function approximation (MLP) is the multilayer perceptron. According to43, the MLP outperformed the support vector machine and radial basis function network in estimating energy consumption for Canadian industrial industries. The input layer, hidden layers, and output layer make up the MLP. Figure 12 depicts the node i, or neuron, in an MLP network. Its activation function, g, is both nonlinear and summer.

The MLP network’s output, \({y_i}\), \(i = 1,2\) , becomes

The set of input \({x_k}\) in the input layer is passed through neurons or nodes and multiplied by weights \({w_k}\) after being known from (22). The neurons \({n_j}\) are then activated by adding it to bias j and activating functions \({g_1}\) in the hidden layer and \({g_2}\) in the output layer. We identified \({g_1}\) as a ’tansig’ and \({g_2}\) as a purelinear model in this work43. We used the Levenberg-Marquardt training technique and gradient descent optimization to determine and estimate the weights and biases of the final outputs, \({y_1}\) and \({y_2}\). In order to find the best combination of effective parameters in the performance of the MLP method, GridSearchCV36 function has been used, so after using the GridSearchCV method, parameters alpha:[0.001, 0.01] ,\(batch \_size\) (Size of minibatches for optimizers):[16, 32, 64],\(hidden \_layer \_sizes\)(The ith element represents the number of neurons in the ith hidden layer):[(100, 50),(50, 50)] , \(learning \_rate \_init\)(The initial learning rate used):[0.001, 0.01], \(max \_iter\)(Maximum number of iterations):[300, 400], \(validation \_fraction\) (The proportion of training data to set aside as validation set for early stopping):[0.1, 0.2]have optimum values of 0.001, 16, (50, 50), 0.001, 300, 0.1 respectively.

Evaluation metrics

While there are many evaluation metrics available today, only a select few can effectively assess the performance of regression-based algorithms. This study illustrates the application of MAE, RMSE, and \({R^2}\). A variety of evaluation criteria were taken into account. In this research, the MAE function is utilized to compute the mean absolute error, which serves as a risk indicator reflecting the expected level of absolute error loss44. The coefficient of determination, commonly known as \({R^2}\), is derived using the \({R^2}\) score function. This function reveals the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (y) that can be explained by the model’s independent variables. The percentage of explained variance is a measure of the model’s goodness of fit and indicates how well it can predict future, unseen data44. As the R-squared value increases, the model’s predictive power and sensitivity to changes in data quantity and weighting improve, as noted by Pearson’s correlation coefficient. According to44, RMSE provides results that are comparable to the best likelihood method. It is important to note that outliers can significantly influence RMSE. A lower RMSE signifies a better model. Metrics based on percentages offer clear insights into the accuracy of predictions and quantify the extent of errors in percentage terms. These metrics are defined in Eqs. (23–26)39.

In this case, the predicted variable is denoted by \({y_i}\), the actual variable by \({y'_i}\), the mean value of the actual variable by y, and the total amount of data collected by n. Additionally, \({R^2}\) should fall between 0 and 1, where positive and negative values indicate direct and inverse correlations, respectively. The range of \(\left[ {0, + \infty } \right]\) also includes RMSE and MAE. When \({R^2}\) is high and both RMSE and MAE are low, it suggests that the model is effectively capturing real-world values and is accurate45.

Classification methods

In summary, signals are decomposed into N modes, or IMFs, through methods like VMD, EEMD, CEEMDAN, EMD, or EWT. Features from each mode are extracted, followed by the selection of specific features that form a set of inputs for the selected classifiers. This allows for the evaluation of each adaptive decomposition technique in terms of damage detection and classification by calculating performance metrics for every classifier.

Empirical mode decomposition (EMD)

The EMD’s flexibility makes it an attractive method since it doesn’t depend on assumptions like linearity or stationarity. This technique breaks down the analyzed signal into several intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), each of which must satisfy two fundamental criteria:

-

(I)

The number of extrema and zero crossings should be equal or differ by at most one.

-

(II)

The envelope value must have a zero mean, determined by the local maxima and minima.

The sifting procedure outlined in Huang et al.’s46 algorithm for extracting IMFs consists of the following steps: Given a temporal series input f(t),

-

(1)

Identify the local maxima and minima of the temporal series.

-

(2)

Apply cubic spline interpolation to construct the envelopes (\({e_{\max }}\), \({e_{\min }}\)) from the identified maxima and minima.

-

(3)

Use the formula \({m_i}(t) = {{({e_{\max }}(t) + {e_{\min }}(t))}/ 2}\) to find the envelope mean.

-

(4)

Remove the value from the previously identified signal: \(h(t) = f(t) - {m_i}(t)\).

-

(5)

Check that the extracted signal h(t) meets the two IMF criteria (the number of maxima and minima and a zero mean). An \(IMF{c_i}(t) = h(t)\) is established if this condition is satisfied. If not, repeat steps 1 through 5 on the extracted signal.

-

(6)

This results in a new residue, \(r(t) = f(t) - {c_i}(t)\). To identify the other IMFs, apply steps 1 through 5 again to the residue r.

The process concludes when it is no longer possible to derive an IMF from a residue, which is then referred to as the final residue \({r_M}\). As shown in (27), the signal is thus decomposed into a specified number of \(IMF{c_i}(t)\) along with the final residue \({r_M}.\)

where N represents the total number of IMFs discovered. The first IMFs isolated by EMD correspond to high frequencies of the signal, and slower components are gradually extracted by the sifting process.

Ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD)

Averaging the decomposition results over a collection of noisy versions of the original signal produces the modes in the noise-assisted data analysis (NADA) method known as EEMD46. This approach aims to address the mode mixing problem while maintaining the physical uniqueness of the signals being decomposed. The procedure can be summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Increase the white noise level of the targeted input series.

-

(2)

Separate the output signal and noise from step 1 into distinct modulations.

-

(3)

Repeat steps 1 and 2 sequentially using different white noise signals.

-

(4)

Finally, calculate the ensemble means of the corresponding IMFs from the decompositions.

The CEEMDAN method was proposed to tackle these challenges46.

Complete ensemble empirical mode decomposition with adaptive noise (CEEMDAN)

The enhanced version of CEEMDAN is presented in this work46. Let \({w^{(i)}}\) represent a realization of unit variance and zero mean Gaussian white noise, \(IM{F_k}\) denote the extracted decomposition modes, \({E_k}(.)\) be the operator that decomposes a signal into its k-th mode using EMD, and M(.) be the operator that calculates the signal mean. Below is a description of the algorithm for an input temporal series f(t):

-

(1)

Decompose the noise-added signal realizations using EMD I: \({f^i}(t) = f(t) + {\beta _0}{E_1}({w^i})\). Next, compute the first residue as \({r_1}(t) = \left\langle {M({f^i}(t))} \right\rangle .{\beta _k} = {\varepsilon _k}std({r_k})\).

-

(2)

Compute \(IM{F_1}(t) = f(t) - {r_1}(t)\), which represents the first mode.

-

(3)

The second mode is derived as \({r_1}(t) = \left\langle {M({f^i}(t))} \right\rangle .{\beta _k} = {\varepsilon _k}std({r_k})\). The second residue is calculated by averaging the local means of the realizations \({r_1}(t) + {\beta _1}{E_2}({w^i})\).

-

(4)

For k = 3,..., K, determine the k-th residue: \({r_k}(t) = \left\langle {M({r_{k - 1}}(t) + {\beta _{k - 1}}{E_k}({w^i}))} \right\rangle\).

-

(5)

Identify the k-th mode: \(IM{F_k}(t) = {r_{k - 1}}(t) - {r_k}(t)\).

-

(6)

For the next k, revert to step 4. Continue this process until the residues, which can only contain one extreme at a time, can no longer be decomposed.

The pyEMD Python (version 3.10.7) package47 was used in this study to implement CEEMDAN, EEMD, and EMD.

Empirical wavelet transform (EWT)

The EWT approach, similar to EMD, focuses on the oscillatory amplitude (AM) and frequency (FM) components of a signal, aiming to extract them while ensuring compact Fourier support. It addresses some limitations of EMD, particularly the lack of a solid mathematical foundation. Before starting the analysis, a few important factors must be considered: (1) the signal must be real-valued to maintain symmetry; and (2) a normalized frequency axis with \(2\pi\) periodicity is utilized, although Shannon’s sampling criterion restricts the analysis to the range \([0,\pi ].\)

1) Identify N distinct empirical modes.

2) Analyze the signal spectrum.

3) Find the local spectral maxima \(N-1\).

4) Define the boundaries \(\omega _n\) as the midpoints between two successive maxima.

5) Establish the EWT filter bank based on the defined \(\omega _n\) limits.

6) Apply this to extract N empirical modes from the input signal.

The limits \({\omega _n}\) are established. Each segment’s boundaries are marked by a transition period with a width of \(2{\tau _n}\), centered at the corresponding \({\omega _n}\). The construction of the filters for each segment is linked to Littlewood-Paley and Meyer wavelets (lowpass for \({\omega _0}\) and bandpass for the other segments)46. As a result, the approximate coefficients (for lower frequencies) and detailed coefficients (for higher frequencies) are defined by an empirical wavelet \({\psi _n}(\omega )\) and an empirical scale function \({\phi _n}(\omega )\).

Variational mode decomposition (VMD)

The VMD approach addresses the limitations of EMD, such as its lack of a solid mathematical foundation and the somewhat inflexible filter bank boundaries of EWT. Tests focused on tone separation and detection indicated that VMD surpassed EMD46. The method begins by assuming that each mode k in the Fourier spectrum has a central frequency \({\omega _k}\) and a defined bandwidth. The following steps outline the process briefly.

1) Generate a single-side band analytic signal using the Hilbert transform of the original signal.

2) Complex harmonic mixing: this step involves multiplying the frequency spectrum of each mode by an exponential function, which is adjusted to the estimated center frequency of that mode, effectively shifting it into the baseband.

3) Determine the bandwidth by calculating the squared \(L^2\) norm of the gradient, or the \(H^1\) norm Gaussian smoothness of the demodulated signal.

The resulting constrained variational problem is expressed as \(\min \{ {u_k}\}, \{ {\omega _k}\}.\)

\({\omega _k}\) represents the corresponding center frequency, while \({u_k}\) denotes the kth mode of the signal (ranging from 1 to K). The complete set of modes and their associated center frequencies are indicated by \({u_k}\) and \({\omega _k}\), respectively. The Dirac function is denoted by \(\delta\), and the input signal that needs to be decomposed is represented by f. Equation (28) can be transformed into an unconstrained problem by incorporating Lagrangian multipliers along with a quadratic penalty term. The following gives the augmented Lagrangian:

All estimated modes in the frequency domain \({{\hat{u}}_k}\) for each iteration n are obtained by applying ADMM to solve (29).

Equation (30) illustrates that modes are updated using a simple Wiener filter. The center of gravity for each mode’s spectrum can be utilized to determine the center frequencies.

The complete breakdown of the initial signal, f(t), is represented by the resulting modes in the time domain, \({u_k}\). Reference48 includes the entire constrained variational optimization problem, offering a more detailed explanation of the method.

In Fig. 13 six first IMF for (a) EMD, (b) EEMD, (c) CEEMDAN, (d) EWT, (e) VMD are plotted.

Feature extraction

The five methods mentioned earlier (EMD, EEMD, CEEMDAN, EWT, and VMD) can be seen as amplitude and frequency modulated signals used for feature extraction. Consequently, the spectral properties of each mode are leveraged to identify the extracted features. The initial feature extracted is the spectral power (SPow), as defined by Eq. (32).

The mode PSD, calculated using Welch’s method46, is represented by \({P_{XX}}\), while N denotes the total number of spectral coefficients. Equation (33) illustrates the Spectral Entropy (SEnt), which serves as the second feature.

The normalized PSD is denoted as \({{{{\bar{P}}}_{XX}}}\). The main frequency component of each mode links to the next three features. After identifying the global maximum of the \({P_{XX}}\), the spectral peak (SP) and its associated frequency (f), which represent the third and fourth features, are utilized to compute the corresponding magnitude. The spectral centroid (SC) for the relevant mode, as outlined in Eq. (34), is the next feature.

where f is the frequency bin and \({\omega (f)}\) and M(f) represent the PSD of the central frequency and magnitude of f, respectively. The AM and FM bandwidths are defined by Eqs. (35–36)46.

where, according to Eq. (37) , A is the analytic signal’s amplitude, E is its energy, and \({\left\langle \omega \right\rangle }\) is the current mode’s center frequency.

In addition, time-domain features like statistical moments and Hjorth parameters46 are extracted. Hjorth complexity (Comp) provides an estimate of the signal’s bandwidth, while Hjorth mobility (Mob) relates to the variance of the signal’s spectrum and is associated with the mean frequency of the signal46. These are defined in Eqs. (38–39):

where Var() is the variance and f(t) is the current signal component.

The skewness is calculated using the following equation and is related to the asymmetry of the signal distribution46:

The symbols \(\sigma\) and \(\mu\) represent the standard deviation and mean, respectively, of the function f(t). The kurtosis, as given by (41), relates to the tails of the distribution produced by the signal.

The mass and stiffness of the structure are affected differently by different kinds of defects, such as cracks and delamination. The shapes of the vibration modes can be changed by various defects, which can also change the way energy is distributed throughout the structure when it oscillates. Spectral Power (SPow) and spectral Centroid (SC) features can be directly impacted by changes in defect type, which can move energy to different frequency bands or change the dominant frequencies. Spectral entropy (SEnt), particularly for more severe or complex damage types, will reflect increased randomness or disorder in the signal as defects alter the complexity and distribution of frequencies. Amplitude and frequency modulation (AM,FM) bandwidths may be widened by nonlinear or evolving defects, signifying more intricate or non-stationary vibration behavior. The type and progression of damage have an impact on both Hjorth Mobility and Complexity, which are sensitive to variations in the signal’s frequency content and complexity. Asymmetry or heavy tails are introduced into the vibration signal’s amplitude distribution by localized or impulsive defects (like abrupt cracks or impacts), which causes discernible changes in skewness and kurtosis.

Feature selection and classification

Feature selection and classification algorithms were carried out using functions from the scikit-learn package49. A feature selection or ranking method is necessary since each signal has a relatively high number of extracted features, and not all of these features are relevant for distinguishing between classes. In this study, recursive feature elimination (RFE)50 was employed to select features using the radial basis function (RBF) support vector machine (SVM) classifier. After that, various classification techniques were evaluated:

-

(1)

Stochastic gradient descent (SGD)51,

-

(2)

support Vector Machine(SVM)52,

-

(3)

Random forest53,

-

(4)

Logistic Regression54.

Five-fold cross-validation was employed to confirm the performance of the classification algorithms. Accuracy (ACC) was used to evaluate performance.

Cross validation

Cross-validation is a statistical method used to compare and evaluate learning algorithms by dividing the data into two parts: one for training the model and the other for validating it. The simplest form of cross-validation is known as k-fold cross-validation. In this method, the data is divided into k segments or folds of equal (or nearly equal) size. Then, k iterations of training and validation are performed, where k-1 folds are used for training and one fold is set aside for validation. During each iteration, one or more learning algorithms create models based on the k-1 folds of data. After the models are trained, they are tested on the validation fold to make predictions. The performance of each learning algorithm on each fold is measured using a specific performance metric, such as accuracy. Once the process is complete, each algorithm will have k samples of the performance metric. The evaluation metrics mentioned in section “Evaluation metrics” represent the average of each performance parameter, and in this study, 5-fold cross-validation was applied to each method.

Result and discussion

This section presents the findings and observations, along with a part that illustrates dataset modeling and model outputs. It includes a comparison of the performances of the generated models and validates the best prediction model. Here, we describe how all regression techniques were implemented using Python (version 3.10.7), showcasing the results in both numerical and graphical formats.

Modeling of datasets and model results

To evaluate the performance of the algorithms, the dataset was randomly split into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) sets. The proposed method utilizes an integrated model with several important parameters that require adjustment. To fine-tune these parameters and improve the accuracy of the results, a thorough grid search cross-validation (GridSearchCV) is employed55. The goodness-of-fit statistics for each model are detailed in the following sections, along with other relevant metrics for assessing performance and robustness, such as RMSE and MAE1. Key variables and regression fit statistics for the training and testing datasets are illustrated in Fig. 14.

In regression methods, a model that is underfitting will exhibit both high training error and high testing error. Conversely, an overfitted model will show low training error but high testing error. As illustrated in Fig. 14, the training and testing errors for the LGBM, BRR, DTR, RFR, FNN and MLP methods are both low and closely aligned, indicating that there is neither overfitting nor underfitting present.

To understand the relationships between variables and the data distribution, two widely used visualization techniques in data analysis and machine learning are the scatter plot and distribution plot. In this study, these plots were employed to illustrate the relationship between actual and predicted defect positions. Scatter plots depict the correlation between two actual defect positions (ground truth) and the predicted defect positions. By examining the data, one can visually assess how closely the actual and predicted defect positions align. Ideally, the points should cluster around a diagonal line, representing the line of perfect prediction, which indicates a strong predictive relationship.

Distribution plots, often referred to as density plots, illustrate the values of a single variable in a distributed format. To analyze the distributions in this context, individual distribution plots are created for both the actual and predicted defect positions. These plots can aid in interpreting the differences between the actual and predicted delamination and crack positions regarding their shape, spread, and central tendency. Changes in these distributions can provide insights into the model’s performance and highlight any systematic biases.

The scatter plot and distribution plot for 4 regression methods with the highest coefficient of determination (\({R^2}\)) are as follows.

Figures 15, 16, 17, 18 show scatter plot and distribution plot for RFR , LGBM , DTR and BRR methods respectively.

Scatter plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions: (a) delamination positions (mm), (b) delamination layer positions, (c) crack positions (mm) and distribution plot of actual and prediction for three defect types positions: (d) delamination positions (mm), (e) delamination layer positions, (f) Crack positions (mm) for RFR.

Scatter plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions: (a) Delamination positions (mm), (b) delamination layer positions, (c) crack positions (mm) and distribution plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions: (d) delamination positions (mm), (e) delamination layer positions, (f) crack positions (mm) for LGBM.

Scatter plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions: (a) delamination positions (mm), (b) delamination layer positions, (c) crack positions (mm) and distribution plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions: (d) delamination positions (mm), (e) delamination layer positions, (f) crack positions (mm) for DTR.

Scatter plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions: (a) delamination positions (mm), (b) delamination layer positions, (c) crack positions (mm) and distribution plot of Actual and Prediction for three defect types positions : (d) delamination positions (mm), (e) delamination layer positions, (f) crack positions (mm) for BRR.

Comparative performance of the models

To evaluate the accuracy of each algorithm in predicting pavement degradation, various machine learning methods are compared using several performance metrics. Lower values of RMSE and MAE, along with a coefficient of determination (\({R^2}\)) approaching 1, indicate better model performance. In fact, \({R^2}\) ranges from 0 to 1, making it essential to choose the model with the highest \({R^2}\) (i.e., closest to 1) when determining the best option. An ideal model not only has a high \({R^2}\) but also exhibits low RMSE and MAE values. To assess the performance of the different regression models tailored for the various techniques, common performance criteria based on their average statistics were established. Additionally, to compare the coefficient of determination (\({R^2}\)) and the errors of each regression method in predicting the testing dataset, reference is made to Figs. 19 and 20.

As shown in Figs. 19 and 20, the random forest regressor, LGBM, and decision tree regressor achieve the highest \({R^2}\) values of 99.80, 99.68, and 99.64, respectively. Moreover, the decision tree regressor, random forest regressor, and LGBM also have the lowest MAE values at 0.02, 0.04, and 0.09, respectively. In addition, the random forest regressor, LGBM, and decision tree regressor show the lowest RMSE values of 0.37, 0.47, and 0.51, respectively.

Prediction of unseen scenarios of known defect types’ position

Given that the model used in this study was developed with limited datasets, it is essential to extend the methods discussed to predict new states that were not part of the training process. To achieve this, 12 untrained multiple defects were introduced to assess the model’s prediction accuracy, utilizing the LGBM method to determine the type and location of these defects. It is important to highlight that the data concerning these 12 defect types were not included in the training, validation, or testing datasets, making them completely unseen. The term “unseen” refers to defects absent from the training, validation, and test datasets, indicating that these cases were not represented in any of these datasets. Khan et al.56 similarly used a convolutional neural network (CNN) to predict unseen delamination cases. It is important to note that the primary distinction between unseen cases and those in the test dataset lies in the fact that the test dataset constitutes a portion (e.g., 15% in this study) of the input dataset, which may overlap with the training and validation datasets. In contrast, unseen cases, being absent from the input dataset, were not included in the training set used for machine learning model training. The prediction results for each of these unseen scenarios of known defect types position are presented in Table 6.

According to Table 6, when the predicted delamination layer is a non-integer, it is rounded to accurately reflect the layer number. Most predicted positions closely match the actual defect locations, with the lowest prediction error at 0% and the highest at 13.34%.

Readers may wonder why a piezoelectric patch is used to excite the structure. The reason is that using a shaker for excitation and an accelerometer to measure the free side acceleration of the structure signal was not cost-effective. To assess the accuracy of the regression models using the structure’s acceleration signals, simulations were conducted without piezoelectric patches. The plate’s free side, or 30 cm from the clamped side, is where the accelerometer is situated. It is worth noting that the accelerometer measures vibrations solely in the Z direction and employs the same sampling strategy as the piezoelectric sensor. The results in Table 7 indicate that the coefficient of determination (\({R^2}\)) and the metrics (MAE, RMSE) demonstrate greater accuracy and lower error in the voltage signals from the piezoelectric sensors compared to the free side acceleration of the structure signals. This highlights the advantages of piezoelectric patches for sensing in composite structures over accelerometer sensors.

Classification using decomposition methods

The multi-class classification accuracy results, which pertain to various mode decomposition methods, feature extraction techniques, and classification methods, are illustrated in Figs. 21, 22, 23, and 24, as discussed in the ’Classification methods’ section of the description covering 5 mode decomposition methods, 8 statistical feature extraction methods, and 4 classification methods. Feature-decomposition/classifier combinations that achieved an accuracy below 50% (e.g., EMD and CEEMDAN with certain classifiers) were excluded from the results. This omission was made to enhance clarity and facilitate a meaningful comparison among methods with accuracies exceeding 50%.

By analyzing the results of the 4 figures above, it is understood that the combination of VMD , Logistic regression then VMD , SVM have 98.26% , 98.14% classification accuracy are the most accurate among the combination of different methods.

Conclusion

In this study, we introduced and validated a novel non-destructive evaluation method for detecting, classifying, and localizing defects in laminated composite structures. An eight-layer graphite/epoxy composite plate with delamination and crack defects served as the test specimen. Piezoelectric actuators applied random voltage stimuli to induce stress responses, which were captured by a network of embedded piezoelectric sensors. We systematically evaluated four regression techniques alongside artificial neural networks, as well as four classification methods, in conjunction with five mode decomposition techniques, to analyze the voltage signatures. Among the regression methods, random forest regression, light gradient boosted machine, and decision tree regression achieved the highest localization accuracy, with \(R^2\) values of 99.8%, 99.68%, and 99.64%, respectively. Additionally, the feedforward neural network attained an \(R^2\) of 99.08%.

Variational mode decomposition, when combined with logistic regression and support vector machine classification, effectively identified defect types with classification accuracies of 98.26% and 98.14%, respectively, based on piezoelectric sensor data. Furthermore, the evaluation metrics demonstrated that regression analyses of piezoelectric sensor signals outperformed those based on structural acceleration responses collected from accelerometers. This methodology enables highly accurate defect localization down to the lamina level and distinguishes between delamination and crack defects with exceptional precision. The results highlight the significant potential of this approach for real-time structural health monitoring and condition-based maintenance.

With further optimization and validation across different composite materials and defect scenarios, this non-destructive evaluation technique could enhance the safety and reliability of load-bearing composite structures. Future research will focus on extending this methodology to a wider range of composite materials and damage conditions to further improve its robustness and applicability.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request

References

Hyndman, R. J. & Koehler, A. B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. Int. J. Forecast. 22(4), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.03.001 (2006).

Bennaceur, M. A. & Xu, Y. Application of the natural element method for the analysis of composite laminated plates. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 87, 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ast.2019.02.038 (2019).

Trzepieciński, T. et al. New advances and future possibilities in forming technology of hybrid metal-polymer composites used in aerospace applications. J. Compos. Sci. 5, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs5080217 (2021).

Vlase, S., Gheorghe, V., Marin, M. & Öchsner, A. Study of structures made of composite materials used in automotive industry. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L: J. Mater. Design Appl. 235(11), 2574–2587. https://doi.org/10.1177/14644207211019767 (2021).

Gheorghe, V., Scutaru, M., Ungureanu, V., Eliza, C. & Ulea, M. New design of composite structures used in automotive engineering. Symmetry 13, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13030383 (2021).

Jeon, J. Y., Gang, S., Park, G., Flynn, E. & Kang, T. Damage detection on composite structures with standing wave excitation and wavenumber analysis. Adv. Compos. Mater 26(sup1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243046.2017.1313577 (2017).

Mohammad-Reza Ashory, A.G.-G. & Kokabi, M.-J. An efficient modal strain energy-based damage detection for laminated composite plates. Adv. Compos. Mater 27(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243046.2017.1301069 (2018).

Gangadhara, Rao T., Boyina, V. K. R. & S.R.V., V. Continuum damage mechanics based failure prediction and damage assessment in laminated composite structures. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 52(4), 2255–2283. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2023.2177860 (2024).

Ghazali, M. & Mahdiabadi, M. K. Delamination and crack detection and localization of a laminated composite plate structure using regression and regression-based neural network methods. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2024.2347504 (2024).

Yang, C. & Oyadiji, S. O. Delamination detection in composite laminate plates using 2d wavelet analysis of modal frequency surface. Comput. Struct. 179, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2016.10.019 (2017).

Hasni, H., Jiao, P., Alavi, A., Lajnef, N. & Masri, S. Structural health monitoring of steel frames using a network of self-powered strain and acceleration sensors: A numerical study. Autom. Constr. 85, 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.10.022 (2017).

Oliver, G., Ancelotti, A. & Gomes, G. Neural network-based damage identification in composite laminated plates using frequency shifts. Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05180-3 (2021).

Sony, S., Gamage, S., Sadhu, A. & Samarabandu, J. Vibration-based multiclass damage detection and localization using long short-term memory networks. Structures 35, 9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2021.10.088 (2021).

Chaupal, P., Rohit, S. & Rajendran, P. Matrix cracking and delamination detection in gfrp laminates using pre-trained cnn models. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 45(3), 136 (2023).

Khan, A. & Kim, H. S. Classification and prediction of multidamages in smart composite laminates using discriminant analysis. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 29(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15376494.2020.1759164 (2022).

Khan, A., Ko, D.-K., Lim, S. C. & Kim, H. S. Structural vibration-based classification and prediction of delamination in smart composite laminates using deep learning neural network. Compos. B Eng. 161, 586–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compositesb.2018.12.118 (2019).

Yessoufou, F. & Zhu, J. Classification and regression-based convolutional neural network and long short-term memory configuration for bridge damage identification using long-term monitoring vibration data. Struct. Health Monit. 22(6), 4027–4054. https://doi.org/10.1177/14759217231161811 (2023).

Nyirandayisabye, R., Li, H., Dong, Q., Hakuzweyezu, T. & Nkinahamira, F. Automatic pavement damage predictions using various machine learning algorithms: evaluation and comparison. Results Eng. 16, 100657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100657 (2022).

Viotti, I. D. & Gomes, G. F. Delamination identification in sandwich composite structures using machine learning techniques. Comput. Struct. 280, 106990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2023.106990 (2023).

Ghazali, M. & Mahdiabadi, M. K. Damage detection and localization in a cantilever beam structure via regression-and-classification-based machine learning. Int. J. Comput. Methods 2025, 2450070. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219876224500701 (2025).

Avarzamani, M., Ghazali, M., Karamooz Mahdiabadi, M. & Farrokhabadi, A. Multiple damage detection in sandwich composite structures with lattice core using regression-based machine learning techniques. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 1–25 (2024).

Ji, D., Lin, J., Gao, F., Hua, J. & Li, W. A deep learning-based spatial gradient reconstruction method for efficient damage identification in composite with high-sparsity lamb wavefield. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 224, 112018 (2025).

Azad, M. M. & Kim, H. S. An explainable artificial intelligence-based approach for reliable damage detection in polymer composite structures using deep learning. Polym. Compos. 46(2), 1536–1551. https://doi.org/10.1002/pc.29055 (2025).

Kim, H. S., Chattopadhyay, A. & Ghoshal, A. Characterization of delamination effect on composite laminates using a new generalized layerwise approach. Comput. Struct. 81(15), 1555–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7949(03)00150-0 (2003).

Kim, H. S., Zhou, X. & Chattopadhyay, A. Interlaminar stress analysis of shell structures with piezoelectric patch including thermal loading. AIAA J. 40(12), 2517–2525. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.1596 (2002).

Kim, H. S., Chattopadhyay, A. & Ghoshal, A. Dynamic analysis of composite laminates with multiple delamination using improved layerwise theory. AIAA J. 41(9), 1771–1779. https://doi.org/10.2514/2.7295 (2003).

Li, D., Liu, Y. & Zhang, X. An extended layerwise method for composite laminated beams with multiple delaminations and matrix cracks. Int. J. Numer. Meth. Eng. 101(6), 407–434 (2015).

Leckey, C. A., Wheeler, K. R., Hafiychuk, V. N., Hafiychuk, H. & Timuçin, D. A. Simulation of guided-wave ultrasound propagation in composite laminates: Benchmark comparisons of numerical codes and experiment. Ultrasonics 84, 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultras.2017.11.002 (2018).