Abstract

This study investigates the developmental status and influencing factors of artificial intelligence (AI) literacy and computational thinking (CT) literacy among undergraduates in China‘s “four new” majors. Guided by the Technology Acceptance Model, Social Cognitive Theory, and Constructivist Learning Theory, the research employs a questionnaire survey to assess student’s AI and CT literacy, as well as the impact of subject background and AI tool usage. Statistical analyses (t-test, ANOVA, Pearson correlation) revealed statistically significant positive associations between dimensions of AI literacy and CT; however, effect sizes were uniformly small (|r| < .10), indicating that these associations—while detectable in a large sample—have limited practical magnitude and should be interpreted with caution. Intelligent Thinking exhibited the comparatively strongest association with critical thinking, though the magnitude warrants cautious interpretation. Disciplinary differences are evident: new engineering students excel at algorithmic thinking, while new liberal arts students show strengths in human–machine collaboration. Moreover, group mean differences were observed across usage-frequency categories; however, we did not fit non-linear models, and further research is needed to verify any non-linear patterns. These findings are consistent with the co-development of AIL and CT and may inform the design of discipline-specific, differentiated educational strategies in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, with the rapid development of artificial intelligence technology, its deep application in various fields of society has put forward new requirements for talent training. Artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking ability have gradually become important literacy of citizens in the information age1. The OECD pointed out in the “Education 2030” report that the era of artificial intelligence needs to cultivate talents with computational thinking and artificial intelligence literacy to adapt to the technological changes in the future society2. Governments have successively introduced relevant policies, such as the US ‘National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan’3, the UK‘s ‘ Artificial Intelligence Industry Strategy‘, etc., all of which emphasize the importance of computational thinking and artificial intelligence education. In China, the State Council‘s “New Generation of Artificial Intelligence Development Plan” clearly proposes to strengthen artificial intelligence education and promote the cultivation of artificial intelligence talents4. The Ministry of Education‘s Compulsory Education Information Technology Curriculum Standard’s5 and ‘ Education Informatization 2.0 Action Plan‘s6 also list computational thinking as one of the core literacy, and require the infiltration of artificial intelligence-related content in the curriculum. Nowadays, the development of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking ability of college students has become a hot topic for scholars at home and abroad. Artificial intelligence literacy mainly includes the understanding of the basic knowledge of artificial intelligence, the application ability of artificial intelligence technology and the ethical consciousness of artificial intelligence7; computational thinking involves core elements such as abstraction, algorithmic thinking, pattern recognition and automation8.

The rapid diffusion of artificial intelligence (AI) presents both opportunities and challenges for higher education. Policymakers and scholars increasingly emphasize not only tool access but also the cultivation of literacies and higher-order thinking necessary to use AI responsibly and productively9,10,11. International frameworks such as UNESCO‘s Guidance for Generative AI in Education and Research and the European Digital Competence Framework (DigComp 2.2) have foregrounded AI-related competencies and digital literacy as priorities for curricula and assessment. Nevertheless, empirical evidence on how everyday AI-tool usage maps onto measurable literacy and thinking outcomes in tertiary education remains limited, especially within discipline-differentiated samples.

Recent studies have redefined artificial intelligence literacy (AIL) as a multidimensional construct encompassing Smart Responsibility, Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking, and Human–Machine Collaborative Innovation12,13. These frameworks emphasize that AIL extends beyond technical proficiency to include ethical, cognitive, and collaborative capacities that enable individuals to understand, evaluate, and co-create with AI systems. At the same time, computational thinking (CT) has evolved from a computer-science-centric skillset toward a broader form of meta-cognitive problem solving that integrates algorithmic reasoning, creativity, and critical reflection in the age of AI14,15. Linking AIL and CT provides an opportunity to understand how literacy-oriented capacities can translate into transferable problem-solving competence in digital contexts.

Most prior work has focused on instrument development or adoption intentions, with fewer studies testing mechanism-oriented models that link use → literacy → thinking. Moreover, cross-national frameworks provide useful comparators but rarely translate directly to curriculum decisions at the discipline level. This study aims to fill these gaps by: (1) measuring AIL and CT across four ‘‘new‘‘ disciplinary clusters (new engineering, new agriculture, new medicine, new liberal arts); (2) testing how daily AI-tool usage relates to AIL and CT; and (3) examining whether AIL mediates the relationship between use and CT.

To enhance alignment with international frameworks, we have conceptually mapped the four dimensions of AI literacy from this study to key competency points in UNESCO and DigComp 2.2: ‘Smart Knowledge and Skill’s aligns with UNESCO‘s emphasis on foundational AI concepts and understanding of data and models, as well as DigComp 2.2‘s ‘Information and Data Literacy‘ and ‘Digital Content Creation (including basic coding/automation)‘; ‘Intelligent Thinking‘ corresponds to UNESCO‘s focus on higher-order cognition (critical analysis, problem modelling, metacognitive reflection) and DigComp 2.2‘s ‘Problem Solving‘ and ‘Creative Thinking and Adaptability‘; ‘Human–Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation‘ resonates with UNESCO‘s principles of human-machine co-creation, contextualised application, and ethical boundary management, while mapping to DigComp 2.2‘s ‘Communication and Collaboration‘ and ‘Co-production and Peer Review‘. This point-to-point conceptual alignment ensures the scale‘s international comparability while providing a transferable reference baseline for cross-system curriculum design.

To provide a clear, testable structure and to respond to reviewer suggestions, we reframe the research aims as the following research questions (RQs):

-

(1)

What are the levels of AI literacy and Computational Thinking among Chinese university students, and how do they differ based on gender, grade, discipline, and place of residence?

-

(2)

To what extent is the frequency of AI tool usage associated with student’s AI literacy and Computational Thinking?

-

(3)

What are the relationships between the dimensions of AI literacy and the components of Computational Thinking?

-

(4)

To what degree do the dimensions of AI literacy predict student’s overall Computational Thinking?

-

(5)

Does AI literacy mediate the relationship between AI tool usage and Computational Thinking?

Theoretical foundations and research framework

Theoretical foundations

Based on the three theoretical frameworks of technology acceptance model, social cognitive theory and constructivist learning theory, this study analyzes the development status and influencing factors of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking of Chinese college students.

We integrate three complementary perspectives. TAM explains adoption and perceived usefulness of technologies; SCT emphasizes triadic reciprocity (person–behavior–environment) and the role of practice and self-efficacy in skill acquisition; Constructivist theories foreground active, contextualized learning and scaffolding. Together, these lenses justify examining both behavioral exposure (hours of use) and mediating cognitive/affective mechanisms (AIL) when predicting CT.

Contribution. Methodologically, this paper provides a large-scale, discipline-aware snapshot and a mechanism test of the use→literacy→CT pathway. Practically, it translates statistical findings into curriculum design principles that prioritize reflective, problem-based integration of AI tools over simple accumulation of tool-hours.

Technology acceptance model

The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), originally proposed by Davis (1989), derives from the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). It posits that user’s behavioral intention to adopt a technology is primarily determined by two key beliefs: Perceived Usefulness (PU)—the extent to which users believe that technology can improve their work or learning performance—and Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU)—the extent to which users perceive the technology as effortless to learn or operate. These perceptions jointly influence Behavioral Intention (BI), which in turn predicts actual use behavior.

TAM has been extensively applied and empirically validated in educational technology research. It provides a solid foundation for understanding how learners and teachers interact with emerging digital tools, including artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced learning environments. Recent studies have progressively extended TAM by integrating contextual and cognitive factors to better capture the complexity of technology use in education. For instance, Wang et al. (2023) integrated TAM with the Task–Technology Fit (TTF) model to analyze college student’s continuance intention toward new e-learning spaces. Their findings showed that the alignment between tasks and technology significantly enhances perceived usefulness and, consequently, sustained learning engagement16. Similarly, Lin and Yu (2024) investigated learner’s acceptance of AI-generated pedagogical agents in language learning videos based on the extended TAM framework. They found that the embodiment and social presence of AI agents positively influenced learner’s perceived usefulness and ease of use, thereby improving their acceptance and learning effectiveness17. These recent advances indicate that TAM remains a robust yet flexible theoretical model that can incorporate new constructs such as task fit, embodiment, and trust when explaining how learners engage with AI-mediated educational technologies.

Building on these empirical insights, continuing to explore TAM in education offers significant value for students, teachers, and institutional stakeholders. For students, TAM-based research reveals the psychological and environmental drivers that shape their motivation and sustained engagement in AI-supported learning. For teachers, it informs the design of learner-centered, technology-enhanced pedagogy by identifying factors that promote ease of integration and perceived instructional effectiveness. For policy and curriculum designers, TAM provides an evidence-based framework for evaluating digital adoption and guiding the development of effective intervention strategies.

However, most TAM-based studies focus primarily on technology acceptance intentions, overlooking deeper outcomes such as literacy acquisition and cognitive skill development. In the context of artificial intelligence education, it becomes necessary to go beyond “whether to use” toward understanding “how technology use cultivates higher-order thinking.” Therefore, this study extends the TAM framework by integrating it with Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) and Constructivist Learning Theory (CLT). This integration allows us to examine how perceived usefulness, self-efficacy, and authentic learning engagement interact to promote student’s AI literacy and computational thinking. Through this perspective, the current study reconceptualizes TAM as not only a model of acceptance but also a mechanism explaining how technology use is transformed into capability development—linking “use,” “literacy,” and “thinking” in a coherent educational process.

Social cognitive theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT) was proposed by Bandura (1986), which emphasizes the interaction between individual behavior, cognition and environment, namely ‘Triadic Reciprocal Determinism‘. The core concepts of SCT include self-efficacy, observational learning, reinforcement mechanism and environmental factors. It emphasizes that individual learning behavior is not only affected by their own cognitive ability, but also regulated by the social environment18. In this study, social cognitive theory provides an important theoretical framework for exploring the formation mechanism of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking ability of college students. Firstly, its ternary interaction perspective provides a systematic explanation path for this study to analyze the synergy of personal characteristics (gender, subject background), behavioral practice (frequency of use of AI tools) and environmental factors (urban-rural differences). Secondly, based on the theory of Vicarious Learning and behavior observation learning point of view, the research pays special attention to the role of technical practice in promoting the development of cognitive ability, and provides a theoretical basis for the study of ‘ the positive correlation between the use of artificial intelligence tools and computational thinking ‘. Finally, the self-efficacy training mechanism emphasized by the theory lays a theoretical foundation for the subsequent development of artificial intelligence education intervention programs based on demonstration teaching and peer learning. Through this theoretical perspective, this study can not only deeply interpret the different performance of different groups in the application ability of artificial intelligence, but also provide theoretical support for the construction of a comprehensive training model integrating individual, behavior and environmental factors, which has important guiding value for promoting the reform of higher education and teaching in the era of artificial intelligence.

Constructivist learning theory

Constructivist learning theory was proposed by Piaget (1950) and Vygotsky (1978). It is believed that knowledge is not passively accepted, but is constructed by learners through active exploration and social interaction on the basis of existing knowledge and experience19. This theory emphasizes Active Construction, Social Interaction, Situated Cognition and Scaffolding20. Piaget ‘s cognitive development theory emphasizes that learners actively construct knowledge through interaction with the environment21, while Vygotsky ‘s sociocultural theory further emphasizes the key role of social interaction and language in learning. In this study, constructivist learning theory provides a framework for analyzing how university students construct AI knowledge through exploration and social collaboration. For instance, in AI education, project-based learning (PjBL) and problem-based learning (PBL) methods create authentic learning situations where students develop deep understanding of AI concepts through peer and teacher interactions22,23. Furthermore, scaffolding instruction-implemented through teacher guidance, AI-assisted teaching tools, or online platform feedback mechanisms-helps students with varying foundational knowledge progressively master computational thinking skills23. This theoretical perspective thus offers crucial guidance for AI education design, emphasizing practical exploration in real problem contexts to foster computational thinking development.

Theoretical discriminants and measurement considerations

While the integration of TAM, SCT, and Constructivism provides a robust framework for understanding the acceptance, self-efficacy, and knowledge-building aspects of AI literacy, we acknowledge the validity of alternative theoretical lenses. For instance, Expectancy-Value Theory could offer a complementary perspective by focusing on how student’s expectations for success and their perceived task value influence their engagement with AI tools. Similarly, developmental models of CT, such as the one proposed by Brennan & Resnick (2012), which tracks the progression from computational concepts to practices and finally to perspectives, provide a nuanced framework that future longitudinal studies could adopt to map the developmental trajectory of CT in the AI context.

Furthermore, the measurement of emerging constructs like AI literacy presents an ongoing challenge for the field. Existing scales, including the one adapted for this study, are continuously evolving. We note that some measures in the literature may conflate foundational knowledge with higher-order thinking skills. In this study, we have sought to achieve discriminant validity between constructs—particularly between the closely related ‘Intelligent Thinking‘ and ‘Computational Thinking‘—through careful item adaptation and theoretical demarcation, positioning ‘Intelligent Thinking‘ as the AI-specific application of cognitive processes that contribute to the broader, domain-general competency of ‘Computational Thinking‘. Future research with larger samples could empirically test this conceptual distinction through advanced psychometric models.

Research framework

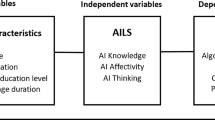

On the basis of the above theoretical basis, this study mainly investigates the development status of college student’s computational thinking (creativity, computational thinking, collaborative ability, critical thinking and problem solving). It examines the relationship between antecedent variables (such as gender, grade, subject category, place of residence and daily use of AI tools) and independent variables (such as Smart Responsibility, Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking and human-machine collaborative hybrid innovation), and has established a research framework for the influencing factors of college student’s computational thinking, as shown in Figure 1.

Antecedent variable

Gender: Gender refers to the biological characteristics of human beings as male or female. In this study, men and women refer to the biological characteristics of the respondents. Grade: refers to the number of years of college students in college. In this study, grades were divided into freshmen (year 1), sophomores (year 2), juniors (year 3) and seniors (year 4), which were used to indicate the current stage of students ‘ learning. Place of residence: This term refers to the geographical location in which a person usually works and lives. In this case, it indicates where students ‘ families live, mainly divided into urban, urban and rural areas. Subject category: refers to the university professional category divided by the Ministry of Education to meet the needs of social development. In this study, the “ four new majors “ classification criteria, new engineering, new agriculture, new medicine, and new liberal arts24. Specifically, the analysis is carried out from the following four colleges: School of Mechanical and Electrical and Intelligent Manufacturing, College of Biological and Agricultural Resources, Li Shizhen Medical College of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Business School. The length of time spent using artificial intelligence tools per day: Measure the time spent by learners using artificial intelligence tools per day. In this study, divided into daily 0-2 hours, 2-4 hours, 4-6 hours and more than 6 hours.

Independent variable

Influencing factors refer to a set of variables or conditions that have a direct or indirect effect on a phenomenon or result. In scientific research, it refers to the independent variables or regulatory variables that can significantly affect the changes of observation indicators, and its mechanism of action may be manifested in different forms of effects such as promotion, inhibition or regulation. In this study, these factors represent the factors or reasons for the development of college student’s computational thinking, and are understood through indicators such as Smart Responsibility, Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking and human-machine collaborative innovation. Smart Responsibility refers to the sense of responsibility, critical thinking and moral concepts that college students should have when using artificial intelligence, and understanding the ethical impact of AI25. In this study, it is the first indicator of influencing factors, which is measured by factors such as intelligent consciousness, intelligent attitude and intelligent ethics. Intelligent knowledge and skills refer to the mastery of AI basic knowledge and practical application by college students. In the AI education guide, the importance of AI basic knowledge is emphasized26. In this study, it is measured by intelligent knowledge, intelligent skills and applications. Intelligent Thinking refers to the way of thinking that uses AI to solve problems. Intelligent Thinking is an important goal of AI education26. In this study, it is measured by computational thinking, data thinking, critical thinking and programming thinking. Human-machine collaborative hybrid innovation refers to how to cooperate with AI to complete tasks and innovate. In an intelligent education environment, human-machine collaboration can improve learning efficiency and promote innovation27. In this study, it is measured by teamwork and intelligent innovation.

Dependent variable

Wing pointed out that computational thinking involves using the basic concepts of computer science to solve problems, design systems, and understand human behavior8. Since Wing proposed computational thinking, the international academic community has systematically explained its essential attributes (abstraction and automation) and core methods (decomposition, abstraction, modeling, recursion, iteration, fault tolerance, divide and conquer, etc.), and demonstrated the interdisciplinary status of CT from the interdisciplinary perspective of computer science, mathematics, engineering and scientific methodology. Rambally emphasizes that computational thinking includes key skills such as creativity, algorithmic thinking, collaboration, critical thinking, and problem solving28. In this study, it is understood through creativity, algorithmic thinking, collaborative ability, critical thinking and problem solving. Creativity refers to the ability to use innovative methods to solve problems. In this study, it is determined by self-cognition of innovation, adaptability and intuitive judgment. The ability of algorithmic thinking to transform problems into computable steps7, in this study, is determined by the proficiency of using mathematical tools to abstract problems. The ability of collaboration to cooperate efficiently in a human-machine collaborative environment is determined by the attitude of knowledge sharing and outcome output in group work in this study. Critical thinking is a kind of self-directed and self-constrained thinking, which aims to make high-quality reasoning in a fair way. In this study, it is determined by the structural analysis and questioning ability of complex problems. Problem solving is generally defined as the ability to understand the environment, identify complex problems, and review relevant information to develop and implement solutions. In this study, it was determined by operational shortcomings and thinking limitations in dealing with difficulties.

Research hypotheses

Guided by the integrated theoretical framework and the research model presented in Fig. 1, the following hypotheses are proposed to be tested:

H1.Higher frequency of AI-tool use is positively associated with student’s AI literacy and computational thinking.

H2.AI literacy mediates the relationship between AI-tool use and computational thinking (i.e., the effect of use on CT is primarily indirect via AIL).

H3.Within AI literacy dimensions, Intelligent Thinking and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation will be stronger positive predictors of CT than Smart Knowledge and Skills alone.

Definition of core concepts

Computational thinking (CT)

In the past few years, research on computational thinking (CT) has entered a stage of continuous expansion and contextualization. With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and emerging digital technologies, CT is increasingly regarded as a key cognitive and problem-solving competency that extends beyond computer science education. Empirical research has progressively shifted its focus from isolated programming skills toward the cultivation of higher-order thinking abilities, including abstraction, decomposition, and algorithmic reasoning, in authentic learning environments.

In the AI era, many studies have explored how CT can be integrated into diverse educational contexts such as data science, intelligent systems, and interdisciplinary project-based learning. These efforts highlight that the development of CT is closely linked to student’s capacity to interact with AI tools, analyze data, and design solutions collaboratively with intelligent systems. The application of AI-supported learning environments has also created new opportunities to promote adaptive feedback, personalized learning, and cognitive scaffolding for CT development.

At the same time, the research focus has gradually expanded from skill acquisition to the broader formation of cognitive and metacognitive competencies. Learners are expected not only to apply computational methods to solve problems but also to reflect on their strategies, monitor their progress, and evaluate the ethical and social implications of technology use. In this sense, the development of CT in the AI era reflects an integrated process combining technical proficiency, critical awareness, and reflective learning.

Overall, recent empirical work suggests that CT should be understood as a multidimensional construct shaped by cognitive, metacognitive, and socio-technical factors. Exploring how AI-related competencies, learning experiences, and cognitive mechanisms jointly influence CT has therefore become a key issue for contemporary educational research.

AI tool use

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools refer to digital applications or platforms that integrate machine learning, natural language processing, and other AI techniques to support tasks such as information retrieval, knowledge generation, language translation, data analysis, and intelligent interaction. In this study, AI tool use specifically refers to Chinese university student’s engagement with AI-powered platforms (e.g., ChatGPT, Baidu, Wenxin, Yiyan, iFLYTEK Spark, Tencent Hunyuan) to assist with learning activities, academic writing, programming exercises, and coursework. Unlike general entertainment use, our focus is on the academic and cognitive application of AI tools, which provides a meaningful context to examine how the frequency and purpose of AI tool use may influence student’s AI literacy and computational thinking.

Research questions

Based on the integrated theoretical framework of TAM, SCT, and Constructivism, this study aims to investigate the development of AI literacy and Computational Thinking among Chinese university students and the relationships between key variables. The following research questions (RQs) guide the inquiry:

-

(1)

What are the levels of AI literacy and Computational Thinking among Chinese university students, and how do they differ based on gender, grade, discipline, and place of residence?

-

(2)

To what extent is the frequency of AI tool usage associated with student’s AI literacy and Computational Thinking?

-

(3)

What are the relationships between the dimensions of AI literacy and the components of Computational Thinking?

-

(4)

To what degree do the dimensions of AI literacy predict student’s overall Computational Thinking?

-

(5)

Does AI literacy mediate the relationship between AI tool usage and Computational Thinking?

Research design

Participants and sampling

This study investigates the current status, influencing factors, and optimization strategies related to artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking among Chinese university students. The participants were undergraduates from H University, a provincial full-time institution in central China, selected based on its representative positioning, student composition, and program structure within the national higher education system. A total of 1,537 questionnaires were distributed between February 5 and March 10, 2025, with 1,466 valid responses retained after excluding incomplete or patterned answers, resulting in an effective recovery rate of 95.38%. The sample included students from four “new disciplines”: new engineering (31%, 454 students), new agriculture (19%, 273 students), new medicine (4%, 58 students), and new liberal arts (47%, 681 students). In terms of gender distribution, 566 participants (39%) were male and 900 (61%) were female. A convenience sampling approach was employed to ensure broad coverage across disciplines and demographic backgrounds. This representative sample offers valuable insights into the AI and computational thinking competencies of students at non-elite Chinese universities, thereby supporting the development of widely applicable educational strategies. Informed consent was secured from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by the Academic Theory Committee of the School of Computer Science at Huanggang Normal University. This sample originates from a provincially-affiliated, non-elite (non-Double First-Class/non-top research-intensive) local comprehensive university, thereby helping to illustrate the baseline and universal landscape of AI literacy and critical thinking at the undergraduate level in China. However, non-elite university and convenience sampling; limited generalizability, small N for New Medicine (n=58).

Measures

The questionnaire was adapted from established scales with proven reliability and validity, consisting of three parts. The first part collected demographic information, including gender, grade, place of residence, discipline, and frequency of AI tool use. The second part assessed artificial intelligence (AI) literacy across four dimensions: Smart Responsibility, Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking, and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation29. The third part measured computational thinking (CT), including creativity, algorithmic thinking, cooperativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving30. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

To ensure psychometric robustness, reliability and validity tests were conducted. As shown in Table 1, Cronbach‘s α for all subscales exceeded 0.80, indicating high internal consistency. The KMO values were above 0.90, and Bartlett‘s test of sphericity was significant (p < .001), suggesting the data were suitable for factor analysis. The cumulative variance contribution rate of each scale dimension is more than 60%, indicating that the scale has good structural validity. Each dimension can effectively explain the main variation of the corresponding construct, which meets the basic requirements of the measurement theory31.

Data collection and processing

Data were collected via the Questionnaire Star online platform. To ensure data quality, responses with excessive missing values, straight-line answers, or abnormal completion times were excluded. After data cleaning, 1,466 valid questionnaires were retained for subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 26.0 and the PROCESS macro (v4.0) for mediation analysis. The analytical procedure included the following steps:

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the distribution of AI literacy and CT.

Reliability and validity analyses (Cronbach‘s α, KMO, Bartlett‘s test, exploratory factor analysis) confirmed the robustness of the scales.

Group difference tests (independent-sample t-tests, one-way ANOVA) examined variations in AI literacy and CT by demographic factors.

Pearson correlation analysis assessed the relationships between AI literacy dimensions and CT.

Multiple regression analysis tested the predictive effects of AI literacy dimensions on CT and its sub-dimensions.

Mediation analysis (bootstrapping, 5,000 resamples) examined whether AI literacy mediated the relationship between AI tool usage and CT. Both direct and indirect effects were estimated with 95% confidence intervals.

In this study, all inferential statistical methods (including t-tests and analysis of variance) were applied based on the fulfillment of their underlying assumptions. First, because normality tests can be overly sensitive in large samples, we additionally inspected histograms and Q–Q plots and found no severe deviations; thus, parametric analyses were considered appropriate. Second, for analysis of variance, we rigorously examined homogeneity of variance across groups using Levene‘s test. All subsequently reported ANOVA results satisfied the assumption of homogeneity of variance (all Levene‘s test *p* > .05). Building upon the fulfillment of these assumptions, we employed parametric tests to ensure statistical power. The significance threshold was set at p <0.05 for all statistical tests.

Considerations on methodology and measurement

This study employs a cross-sectional, self-report design, which is an efficient and established approach for initial, large-scale exploration of the relationships between AIL and CT across diverse disciplinary contexts. Limitations include cross-sectional self-report data (which raise the possibility of common method variance). Although we conducted procedural safeguards in questionnaire design and excluded low-quality responses, we did not report a formal Harman’s single-factor or marker variable test in the present manuscript — future analyses should explicitly test CMV and incorporate objective performance measures or multi-informant data where feasible. The convenience sampling from a single university, while providing a rich, context-specific snapshot, limits the generalizability of our findings, and the small cell size for the ‘New Medicine‘ group (n=58) necessitates caution in interpreting disciplinary comparisons involving this cohort.

A particular conceptual and methodological challenge lies in distinguishing the closely related constructs of ‘Intelligent Thinking‘ (a dimension of AIL) and ‘Computational Thinking‘ (the outcome variable). While our factor analysis confirmed the empirical separation of these scales within our dataset, we recognize the theoretical and semantic overlap. This overlap, however, may reflect the intrinsic conceptual linkage whereby AI literacy acts as a catalyst and concrete instantiation of computational thinking in the AI domain. Therefore, the strong correlation observed is not merely a measurement artifact but is theoretically plausible and central to our research hypotheses.

Ethical considerations

This study adhered to the ethical standards of the Chinese Ministry of Education and the Helsinki Declaration. Ethical approval was obtained from the Academic Theory Committee of the School of Computer Science, Huanggang Normal University (approval number: HGNU-CS-20250110). All participants were informed of the study‘s purpose, assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Results analysis and discussion

Basic characteristics of students

As shown in Table 2, this survey collected valid data from 1,466 college students. The participants were mainly women (900, 61%) and men (566, 39%). This gender distribution is consistent with the trend of the increasing proportion of women in higher education in China. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, in 2025, women will account for more than men in all types of higher education, with 1.963 million female graduate students, accounting for 50.6% of all graduate students; ordinary undergraduate and vocational undergraduate. There are 18.872 million and 5.643 million female students in adult undergraduate colleges, accounting for 50.0% and 56.0% respectively32. In terms of family residence, rural students account for the highest proportion (715 people, 49%), urban and urban students account for 29% (428 people) and 22% (323 people) respectively, reflecting the policy effect of China ‘s higher education coverage extending to counties33. The grade distribution shows a typical pyramid structure: the proportion of freshmen is the highest (626,43%), and the proportion decreases with the increase of grade, and the proportion of senior students is only 6% (93), which is related to the high participation of basic courses in the middle and lower grades and the diversion of internships in the upper grades. According to the professional distribution, the proportion of new liberal arts students is prominent (681, 47%), followed by new engineering (454, 31%), new agriculture (273, 19%) and new medicine (58, 4%), which is consistent with the current trend of interdisciplinary expansion under the background of high ‘ new liberal arts ‘ construction33. In terms of the duration of artificial intelligence use, 48% of respondents (704people) used 0-2 hours a day, and 24% (347people) used 2-4 hours a day, showing a clear right-skewed distribution. Studies have shown that more than 60% of college students use artificial intelligence tools no more than 3 hours a week, and less than 30% of students use artificial intelligence tools for more than 3 hours a week34. This shows that the penetration of artificial intelligence in college education scenes is still in its infancy, and the improvement of college students ‘ artificial intelligence literacy still needs to be strengthened from the breadth and depth of tool use, especially the application density in teaching practice and learning tasks needs to be further expanded. Daily AI-use duration was collected as an ordinal variable (1=0-2h, 2=2-4h, 3=4-6h, 4=>6h). For primary analyses we treated it as approximately continuous to examine linear trends; to verify robustness we also ran categorical ANOVA/post-hoc tests — results were consistent in direction. We acknowledge that treating ordinal categories as interval may obscure non-linear effects; future analyses should test non-linear models or use finer-grained time measures. This approach is widely accepted in social science and educational research. Its rationale lies in two key points: First, the four categories of this variable exhibit a clear temporal sequence and approximately equidistant numerical intervals. Second, treating it as a continuous variable allows for more comprehensive utilization of data information, enabling a more precise revelation of the dose-response relationship between usage duration and literacy levels, thereby avoiding the loss of trend information due to overly coarse categorization. As a robustness check, we also conducted an analysis using analysis of variance (treating it as a categorical variable). The results were fully consistent in direction with those obtained when treating it as a continuous variable, further supporting the validity of our approach.

Analysis of the influence of student’s characteristics on artificial intelligence literacy

Using analysis of variance (ANOVA), the relationships between student’s demographic and learning characteristics—including gender, grade level, discipline category, place of residence, and daily usage time of artificial intelligence (AI) tools—and their AI literacy were examined. The detailed statistical results are presented in Table 3 (gender differences) and Table 4 (differences across other characteristics).

As shown in Table 3, the independent-samples t-test results indicate no statistically significant differences between male and female students in any dimension of AI literacy (AI Responsibility: t=1.519, p=0.129; AI Knowledge and Skills: t=0.734, p=0.463; AI Thinking: t=1.704, p=0.089; Human–Machine Collaborative Innovation: t=0.329, p=0.742, all p>0.05). This suggests that gender does not exert a key influence on overall AI literacy, which is consistent with the findings of Diao et al. (2023) showing minimal gender impact on AI acceptance intention35.

Further analysis using Table 4 revealed that grade level significantly affects certain dimensions of AI literacy. “AI Thinking” (F=2.956, p=0.031) and “Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation” (F=3.346, p=0.019) show significant differences, with sophomores and juniors scoring higher than freshmen (all p<0.05). However, senior students did not continue to show significant improvement, possibly due to factors such as graduation internships, as similarly noted by Chan and Hu36.

Regarding place of residence, a clear gradient effect is observed (see Table 4). Urban students outperform township and rural students in AI Responsibility (F=6.314, p=0.002), AI Knowledge and Skills (F=6.798, p=0.001), and AI Thinking (F=3.948, p=0.020), showing a distinct “city > town > rural” pattern. This result indicates that the technological environment plays a crucial role in enhancing AI literacy37, echoing Sublime and Renna‘s findings that frequent exposure to AI tools contributes to higher competence development among urban students38. However, the Human–Machine Collaboration dimension shows no significant geographical differences (F=1.743, p=0.175).

Differences across disciplinary backgrounds are also evident in Table 4. Significant variations appear in AI Thinking (F=3.461, p=0.016) and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation (F=3.242, p=0.021), where students majoring in new engineering and new liberal arts score higher than those in new agriculture. New medical students, however, perform near the intermediate level, suggesting that AI integration in medical curricula still needs to be strengthened. These findings align with Zhang Chi‘s research, which notes that disciplinary contexts influence the depth and breadth of AI application39.

Finally, daily usage duration of artificial intelligence tools exhibits a significant positive impact across multiple dimensions of AI literacy (see Table 4). AI Responsibility (F=3.958, p=0.008) is significantly higher among students using AI tools for more than six hours per day compared with those using them for 0–2 hours. Similarly, increased daily usage significantly enhances AI Knowledge and Skills (F=4.485, p=0.004) and AI Thinking (F=3.061, p=0.027). Notably, even moderate use (2–4 hours per day) yields meaningful improvements, providing empirical support for rational AI tool integration in higher education39. Human–Machine Collaboration, however, does not show a statistically significant relationship (F=2.027, p=0.108).

In summary, both residence background and daily AI tool usage time emerge as key influencing factors of AI literacy, whereas gender and discipline exert comparatively weaker effects. These results collectively underscore the role of environmental exposure and practical engagement in fostering student’s comprehensive AI literacy.

To strictly control the potential inflation of Type I errors from multiple comparisons, this study applied Bonferroni correction to all pairwise post-hoc comparisons following one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results reveal the specific groups responsible for differences in student’s AI literacy.

Impact of AI Tool Usage Duration: Among the four dimensions of AI literacy, both AI Responsibility and AI Knowledge & Skills exhibited significant usage duration effects. Post-hoc comparisons after Bonferroni correction indicated that students using AI tools for over 6 hours daily scored significantly higher on AI Responsibility than those using 0–2 hours (corrected *p* = 0.034). Regarding AI Knowledge and Skills, both the 2–4 hours per day (corrected *p* = 0.016) and over 6 hours per day (corrected *p* = 0.029) groups scored significantly higher than the 0–2 hours group. However, no significant differences were found across usage duration groups in the dimensions of AI-driven thinking and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation (all corrected p > 0.05). This suggests that moderate-to-high AI tool usage correlates with improvements in foundational competencies like ethical responsibility and knowledge/skills, but simply extending usage time may not be a key factor for developing higher-order thinking patterns and collaborative innovation capabilities.

Grade-level differences analysis: Univariate ANOVA revealed no significant differences across grade levels in any AI literacy dimension (all *p* > 0.05). Post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected comparisons further confirmed that pairwise comparisons between any two grade levels failed to reach statistical significance (all corrected *p* > 0.05). This result suggests that AI literacy levels among university students in this sample remain relatively stable across undergraduate grades, potentially reflecting overall consistency in AI-related learning opportunities during university education.

Differences by Discipline Category: Bonferroni-corrected interdisciplinary comparisons revealed significant disciplinary characteristics. Regarding Intelligent Thinking, students in new engineering disciplines significantly outperformed those in new agricultural disciplines (corrected *p* = 0.024), while students in new liberal arts disciplines also significantly outperformed those in new agricultural disciplines (corrected *p* = 0.03). A similar pattern emerged in the Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation dimension, where both new engineering (corrected *p* = 0.045) and new liberal arts (corrected *p* = 0.018) students significantly outperformed new agricultural science students. All other pairwise comparisons between disciplines were not significant after correction. These findings highlight differing emphases across disciplines in cultivating advanced AI literacy. New Agricultural Science students lag relatively in intelligent thinking and collaborative innovation, warranting attention in future interdisciplinary educational design.

Based on the results of Pearson‘s correlation analysis, as shown in Table 5, the relationships between demographic variables such as gender, grade level, place of residence, and academic discipline and the dimensions of AI literacy (Smart Responsibility, Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking, and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation) were systematically examined. Effect sizes were reported alongside p-values. For correlation analyses we report Pearson‘s r and the proportion of variance explained (r2). For regression analyses we report standardized regression coefficients (β) and, where relevant, estimate local effect sizes using Cohen‘s f2 (f2 = R2/(1−R2)). Following Cohen (1988)39, f2 values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 are interpreted as small, medium and large effects, respectively. We also interpret statistical significance in light of effect sizes and sample size, avoiding over-interpretation of effects that are statistically significant but negligible in magnitude.

The analysis of grade level showed that only the Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation dimension showed a weak positive correlation (r=0.063, p=0.016<0.05). Furthermore, when discussing the influence of the residence factor on AI literacy, residence showed a relatively significant effect. Urban sources significantly outperformed rural sources in the dimensions of Smart Responsibility (r=-0.091, p=0.001), Smart Knowledge and Skills (r=-0.095, p<0.001), and Intelligent Thinking (r=-0.073, p=0.005), and the effect sizes, although small (|r|<0.1), were statistically significant. Multiple comparisons showed a gradient difference of city>town>rural (p<0.05), a result that may reflect the ongoing impact of the urban-rural digital divide on AI literacy development, consistent with the findings of existing research on geographic differences in digital literacy40. The correlation between disciplinary background and AI literacy was not significant overall, and despite the highest percentage of new liberal arts students in the sample (47%), the disciplinary differences did not create a significant differentiation in literacy levels, which may be related to the interdisciplinary penetration of AI education. However, the most important finding was that daily time spent using AI tools was significantly and positively correlated with all dimensions of literacy, e.g., Smart Responsibility: r=0.084(p=0.001); Smart Knowledge and Skills: r=0.079(p=0.003); Intelligent Thinking: r=0.06(p=0.01); and Human-Computer Collaboration: r=0.054(p=0.037). Although the effect sizes were small (r<0.1), the pattern of consistently significant associations suggests that increasing the frequency of AI tool use may have a cumulative effect on literacy development, consistent with the results of existing research41. This finding provides empirical support for the theoretical hypothesis that practice promotes literacy development.

Although several correlations reached statistical significance, their magnitudes were very small. For example, observed Pearson correlations ranged from r = 0.054 to r = 0.084; these correspond to r2 = 0.0029–0.0071, i.e. 0.29%–0.71% of the variance explained. Converted to regression local effect sizes, these values correspond to Cohen‘s f2 ≈ 0.0029–0.0071, which is far below the conventional “small” threshold of f2 = 0.02. Therefore, while some associations are detectable in our (relatively large) sample, their practical or educational impact at the individual level is likely negligible.

Analysis of the influence of student’s characteristics on computational thinking

As shown in Tables 6 and 7, firstly, from the perspective of gender, the data analysis shows that boys are significantly better than girls in the dimensions of algorithmic thinking (t=3.875, p<0.001), collaborative thinking (t=2.114, p=0.035), and critical thinking (t=2.836, p=0.005), which may reflect the influence of gender stereotypes on specific thinking dimensions in STEM education. This result may reflect the influence of gender stereotypes in STEM education on specific dimensions of thinking, and is partially consistent with the findings of existing research on the “boy’s advantage in logical reasoning tasks”. For example, Notably, the gender differences effect sizes were small (Cohen‘s d<0.3) and the actual educational significance was limited. In addition, the grade difference analysis showed that sophomore and junior students were significantly better than freshmen students in creativity (F=3.255, p=0.021) and algorithmic thinking (F=3.617, p=0.013), a progressive developmental feature consistent with the theory of cognitive developmental stages, suggesting that after 1-2 years of higher education, students may gain systematic in their abstract thinking and creative abilities enhancement. In terms of place of residence, the data showed that the factor of place of residence only had a marginal effect on creativity (F=2.95, p=0.053), and the other dimensions did not show any significant difference, which is different from the results of the analysis of Artificial Intelligence Literacy, and that the urban-rural difference in Computational Thinking is not obvious, which may reflect the universality of logical thinking training in the basic education stage.The analysis of disciplines found that there are significant disciplinary differences in algorithmic thinking (F=5.352, p=0.001), and the new engineering students (M=21.57) significantly outperform the new agricultural students (M=20.26), while the other dimensions do not show any significant differences (p>0.05), which is closely related to the professional curriculum, and the intensive training of algorithmic and logical thinking in engineering disciplines may have a cumulative effect. It is worth noting that the length of daily use of AI tools was significantly positively correlated with all dimensions of computational thinking (p<0.05), a result that is highly consistent with the theory of technology-enhanced learning, suggesting that there is a dose-effect relationship between the frequency of use of AI tools and the development of computational thinking. It is important to emphasize that although there are statistically significant differences in some dimensions, the effect sizes of these differences are small and the actual educational significance may be limited. Therefore, in educational practice, attention should be paid to how to provide equal resources and opportunities for all students, especially in eliminating gender stereotypes and promoting interdisciplinary collaboration. In addition, rationally guiding students to use AI tools may help to improve their computational thinking skills.

As shown in Table 8, the Pearson correlation coefficient analysis led to the following observations: firstly, Grade level was significantly and positively associated with creativity (r=0.068, p=0.01) and algorithmic thinking (r=0.071, p=0.007), reflecting the cumulative fostering effect of higher education on higher-order thinking. This finding is consistent with Piaget‘s theory of stages of cognitive development, which emphasizes that student’s thinking skills develop and deepen as their educational level increases42. The analysis of academic disciplines showed that the new engineering students were significantly better than the students of other disciplines in algorithmic thinking (r=-0.061, p=0.019), highlighting the key role of the specialized curriculum in the development of computational thinking. This result is closely related to the intensive training of algorithmic and logical thinking in engineering disciplines. Place of residence was only weakly negatively correlated with creativity (r=-0.063, p=0.015), with a small effect size, suggesting a limited effect of urban-rural differences, which may reflect the prevalence of logical thinking training at the basic education level, making urban-rural differences in computational thinking insignificant. Notably, the length of daily AI use was significantly and positively correlated with all dimensions of computational thinking (p<0.05), yet the effect sizes were small (r ≈ .05–.08; r2 < 1%), indicating limited practical impact at the individual level. These findings have important implications for educational practices in the AI era: first, gender-inclusive teaching strategies should be designed, with special attention to the cultivation of female students in dimensions such as algorithmic thinking; second, a spiraling curriculum needs to be constructed, with a focus on strengthening the development of competencies during the sophomore transition period; and finally, it is recommended that AI tools be deeply integrated into the curriculum. and that a project-based hands-on teaching model be established. The results of this study not only expand the understanding of the influencing factors of computational thinking, but also provide empirical evidence for the education of AI literacy in colleges and universities, but the limitations of cross-sectional studies need to be noted, and it is recommended that the causal relationship be further verified by combining with a longitudinal tracking design in the future.

Correlation analysis of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking

As shown in Table 9, the analysis results show that multiple dimensions of AI literacy and computational thinking show significant positive correlations (p<0.001), indicating that there is a close connection between the two. Specifically, the correlation between Intelligent Thinking and computational thinking is the most significant, with a correlation coefficient of 0.708 (p<0.001), indicating that Intelligent Thinking (e.g., logical reasoning, pattern recognition, etc.) has an important impact on the cultivation of computational thinking. Secondly, Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation (r=0.681, p<0.001), creativity (r=0.719, p<0.001), and critical thinking (r=0.760, p<0.001) also showed strong correlation with computational thinking. This suggests that in the era of artificial intelligence, the ability to innovate and analyze critically are important contributors to the development of computational thinking. In addition, the significant correlation between collaborative ability (r=0.750, p<0.001) and algorithmic thinking (r=0.494, p<0.001) further corroborates the critical role of teamwork and structured problem solving in computational thinking. It is important to note that despite the relatively weak correlation between Smart Responsibility (r=0.458, p<0.001) and Smart Knowledge and Skills (r=0.526, p<0.001) and Computational Thinking, the correlation still reached a significant level. This may be due to the fact that the effects of ethical awareness and basic knowledge on computational thinking are more indirectly realized through other higher-order competencies (e.g., Intelligent Thinking or creativity). Therefore, in educational practices, attention should be paid to how to provide equal resources and opportunities for all students, especially in eliminating gender stereotypes and promoting interdisciplinary cooperation. In addition, rationally guiding students to use AI tools may help improve their computational thinking skills.

Multiple regression analysis of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking

In order to further test the predictive effect of artificial intelligence literacy (AIL) on computational thinking (CT), this study constructed a multiple linear regression model using the total CT score as the dependent variable and the four dimensions of AIL—Intelligent Responsibility, Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking, and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation—as independent variables. The results are presented in Table 10.

To detect potential multicollinearity, tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values were examined. In the initial model, Intelligent Thinking had a VIF of 5.765, indicating moderate multicollinearity. To address this issue, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed on the three highly correlated dimensions—Smart Knowledge and Skills, Intelligent Thinking, and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation—and the first principal component was extracted as the Intelligent Literacy Factor to reduce redundancy among predictors. Subsequently, all continuous predictors were mean-centered, and an interaction term (centered Intelligent Responsibility × centered Intelligent Literacy Factor) was created. The corrected model exhibited tolerances greater than 0.45, with a maximum VIF of 2.209, suggesting that multicollinearity was effectively mitigated. The regression coefficients, standard errors, standardized betas, t values, and significance levels of the corrected model are reported in Table 11.

To further verify the robustness of the corrected model, a ridge regression was conducted with a ridge parameter k=1. The ridge model yielded R=0.968, R2=0.937, adjusted R2=0.875, and F=14.999, p=0.026. The standardized coefficients of the three predictors (≈ 0.25 each) retained the same direction as in the OLS model, indicating that the ridge penalty stabilized the coefficients without altering their interpretive meaning. These results confirm that the statistical estimates of the corrected model are robust under regularization, ensuring the overall consistency and validity of the regression results (see Appendix S1 for detailed ridge regression output).

Specifically, the corrected regression results show that Intelligent Responsibility has a significant positive predictive effect on CT (β = 0.094, t = 3.933, p < 0.001), indicating that the enhancement of student’s ethical awareness and critical consciousness in AI contributes to the improvement of their overall CT level. In contrast, Smart Knowledge and Skills exhibits a negative regression coefficient (β = −0.096, t = −3.003, p = 0.003). This significant negative relationship, despite a positive zero-order correlation (r = 0.526, p < 0.001), suggests a potential statistical suppression effect [1, 2]. One interpretation is that within the multivariate model, Smart Knowledge and Skills shares overlapping variance with other predictors (e.g., Intelligent Thinking) not directly related to CT; when this shared variance is controlled, its unique contribution becomes negative. This implies that instruction emphasizing discrete AI knowledge and procedural skills, if not integrated with higher-order cognitive engagement, may not uniquely promote CT development.

Among the predictors, Intelligent Thinking (β = 0.451, t = 12.875, p < 0.001) and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation (β = 0.422, t = 14.259, p < 0.001) are the most influential positive factors. These findings suggest that abstract, digital, and programming-oriented thinking processes, as well as innovative collaboration with AI systems, play core roles in promoting student’s problem-solving and computational abilities. Collectively, these results are consistent with the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), underscoring that deep cognitive engagement and human–AI interaction experiences contribute more to CT development than the mere mastery of factual knowledge or procedural skills.

In summary, through the correction and verification procedures (PCA, centering, and ridge regression), this section ensures statistical consistency and robustness in the analysis of AIL‘s predictive effect on CT. These results provide a reliable empirical foundation for subsequent mediation analyses exploring the internal mechanism linking AI literacy and computational thinking.

Robustness checks for the negative coefficient of “Smart Knowledge and Skills”

To further examine whether the negative regression coefficient of Smart Knowledge and Skills was a statistical artifact or a theoretically meaningful suppression effect, two additional analyses were conducted.

Partial correlation analysis

When controlling for Intelligent Responsibility, Intelligent Thinking, and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation, the partial correlation between IKS and Computational Thinking (CT) remained weakly negative (r = −0.078, p = .003). This suggests that after removing the shared variance contributed by higher-order cognitive and collaborative dimensions, the unique component of IKS—primarily factual and procedural knowledge—shows a small inverse association with CT. The negative unique association likely reflects shared variance with higher-order dimensions rather than a detrimental effect of knowledge per se. This supports the interpretation of a suppression effect, rather than a simple negative causal relation (i.e., “more knowledge leads to lower CT”).

Collinearity sensitivity analysis

To test the sensitivity of this result, the regression model was re-estimated by removing or combining the IKS dimension using the PCA-derived composite factor (Intelligent Literacy Factor). The overall explanatory power of the model (R2 = 0.937) and the coefficients of other predictors (Intelligent Thinking and Human–Machine Collaboration) remained stable, indicating that the negative sign of IKS is driven by shared variance among highly correlated cognitive dimensions rather than by model instability.

Visual inspection

A partial regression plot (see Appendix S2) further illustrates the residual relationship between IKS and CT, showing a slight downward slope when the effects of other predictors are statistically controlled. This pattern confirms that the negative coefficient reflects a conditional suppression phenomenon rather than a genuine negative educational outcome.These robustness analyses confirm that the negative coefficient of IKS represents a statistical suppression effect rather than a paradoxical or spurious finding. In pedagogical terms, this result reflects a potential knowledge–application gap: the isolated acquisition of AI-related factual or procedural knowledge may not automatically enhance computational thinking unless such knowledge is actively integrated into reflective and application-oriented learning contexts.

This finding echoes prior educational research suggesting that “knowledge without cognitive engagement” can even constrain higher-order thinking development by promoting rote or fragmented learning approaches. Therefore, future AI literacy education should align knowledge instruction with applied reasoning, problem-solving, and reflective learning—ensuring that technical proficiency co-evolves with conceptual and metacognitive growth.

Mediation analysis of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking

To examine the mediating path “AI tool usage time (X) → AI literacy (M) → computational thinking (Y),” we employed Haye’s PROCESS macro (Model 4) for guided mediational analysis, using 5,000 bootstrap samples to estimate 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects. Results indicate: The total effect of AI tool usage time on CT is significant (c = 1.263, Boot SE = 0.414, 95% CI [0.450, 2.075]). After including AI literacy as a mediator, the indirect effect remains significant (ab = 0.985, Boot SE = 0.334, 95% CI [0.316, 1.645]), while the direct effect became non-significant after controlling for mediation (c‘ = 0.277, Boot SE = 0.263, 95% CI [−0.234, 0.794]), as shown in Table 12. This result aligns with the “indirect-only mediation” pattern (i.e., effects primarily transmitted through M), indicating that the impact of AI tool usage on CT is mainly achieved by enhancing student’s AI literacy (the mediating effect accounts for approximately 78% of the total effect), as shown in Table 13.

Educational enlightenment: Taking ‘use-literacy-thinking’ as the main line of design: through project-based, contextualized and assessable AI ethics and data / algorithm units, the use of tools is explicitly transformed into literacy construction, so as to enhance computational thinking. The course emphasizes 2-4 hours and other ‘effective use’ scene design, focusing on ‘quality’ rather than ‘quantity’.

Limitations and robustness: Cross-sectional design support’s evidence consistent with the causal model ‘, and longitudinal / quasi-experiments (such as cross-lagged, randomized item strength) are still needed to verify causality. The effect of mediation robustness and sub-dimension parallel mediation (Intelligent Thinking, human-machine collaboration) can be compared to enhance persuasion after adding control variables in the appendix.

Conclusion: The length of AI use does not directly improve computational thinking. It mainly plays a role by improving artificial intelligence literacy (especially Intelligent Thinking and human-machine collaboration as the hub), which provides empirical support for the higher education teaching design of “ promoting literacy by use and thinking by literacy,” and strengthens the hierarchy of full-text evidence in method.

Testing of research hypotheses

The findings of this study provide comprehensive evidence to evaluate the proposed research hypotheses. Overall, the data largely support our theoretical model, confirming the significant role of AI tool usage and AI literacy, particularly its higher-order dimensions, in fostering computational thinking.

Support for H1

Hypothesis 1 postulated a positive association between AI tool usage frequency and both AI literacy and computational thinking. Our results offer partial support for this hypothesis. A significant, albeit weak, positive correlation was observed between usage time and all dimensions of AI literacy (Table 5) and most components of computational thinking (Table 8). Furthermore, ANOVA results indicated that students with higher daily usage (e.g., 2-4 hours and >6 hours) scored significantly higher on several AI literacy dimensions and CT components compared to the low-usage group (0-2 hours) (Tables 4 & 7). This aligns with the Technology Acceptance Model and Social Cognitive Theory, suggesting that behavioral engagement with AI tools forms a foundation for competency development. However, the small effect sizes indicate that mere frequency of use is a necessary but insufficient condition, underscoring the importance of quality and context of use.

Support for H2

Hypothesis 2 proposed that AI literacy mediates the relationship between AI tool usage and computational thinking. The mediation analysis (Section "Mediation analysis of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking", Tables 11 & 12) strongly supports this hypothesis. The significant total effect of usage on CT (c = 1.263) became non-significant (c‘ = 0.277) after introducing AI literacy as a mediator, while the indirect effect was significant (ab = 0.985). This “indirect-only” mediation pattern indicates that the impact of AI tool usage on computational thinking is almost entirely transmitted through the enhancement of student’s AI literacy, which accounts for approximately 78% of the total effect. These results provide tentative empirical support for the proposed use→literacy→CT pathway, indicating that AI tool exposure is associated with higher AIL which, in turn, relates to CT. However, given effect sizes and design limits, these findings should be viewed as preliminary and hypothesis-generating rather than definitive.

Support for H3

Hypothesis 3 predicted that among the AI literacy dimensions, Intelligent Thinking and Human-Machine Collaboration Hybrid Innovation would be more potent predictors of CT than Smart Knowledge and Skills. The multiple regression results (Section "Multiple regression analysis of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking", Table 10) provide robust support for H3. As anticipated, Intelligent Thinking (β = 0.451, p < 0.001) and Human–Machine Collaboration (β = 0.422, p < 0.001) emerged as the strongest positive predictors of overall computational thinking. Conversely, Smart Knowledge and Skills exhibited a significant negative unique contribution (β = -0.096, p = 0.003) in the multivariate model, despite a positive zero-order correlation. This suppression effect reinforces H3, suggesting that when the variance shared with higher-order cognitive and collaborative capacities is controlled, a focus on isolated knowledge and procedural skills does not confer a unique advantage for CT development and may even be inversely related if not well-integrated. This underscores the paramount importance of fostering deep cognitive strategies and collaborative innovation abilities over the mere accumulation of factual knowledge in AI education.

Optimization strategies and suggestions

Curriculum design

Interdisciplinary integration

The development of AI literacy and computational thinking requires breaking down disciplinary boundaries and promoting student’s understanding of the integration of multidisciplinary knowledge through interdisciplinary integration. Students from different disciplinary backgrounds, such as New Engineering and New Liberal Arts, have different learning strengths and challenges. Xie et al. emphasized the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in AI education by collaborating with high school teachers in the humanities and STEM fields to co-design an AI education curriculum 43. Therefore, when designing curricula, we should combine the core content of computational thinking and AI according to the characteristics of different disciplines and design curricular modules that meet the needs of the disciplines. Especially for students of new liberal arts and new medical sciences, course contents related to human-computer collaboration and intelligent innovation should be increased to cultivate their innovative thinking and interdisciplinary problem solving ability. Through interdisciplinary project-based learning and practical teaching, it can improve student’s comprehensive quality and promote their collaborative ability and critical thinking development in the application of AI technology.Because the sample derives from a single provincial comprehensive university and used convenience sampling (and because the New-Medicine subgroup was small, n=58), recommendations for broad curricular reform should be considered provisional until replicated in nationally representative or multi-institutional samples.

Layered teaching

Considering the differences in the foundations and developmental stages of students in higher education, the curriculum should be designed to enable tiered instruction. Studies have shown that sophomores and juniors perform better on certain dimensions of computational thinking and AI literacy, while the performance of juniors may not consistently improve, possibly limited by time allocation during the graduation season. Chiu et al. created and evaluated an AI curriculum in secondary schools in Hong Kong, emphasizing the importance of designing AI curricula for students at different educational stages44. Therefore, individualized instruction should be implemented according to student’s grade level, professional background, and ability level, and curriculum content should be designed in a hierarchical manner, progressing gradually from basic to advanced levels to ensure that all students can build on their foundation. For example, beginners can start with basic programming languages and algorithms, while students with a certain level of foundation can improve their comprehensive abilities through more complex AI applications and innovative projects.

Resource balance

Urban-rural linkage

There is a gap between urban and rural students in artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking ability, especially in terms of Smart Responsibility and Intelligent Thinking. This difference may be related to the urban-rural digital divide and the unbalanced distribution of educational resources. Therefore, colleges and universities should strengthen the resource linkage between urban and rural areas, with the help of online education platform, virtual laboratory and remote teaching technology, break the geographical restrictions, and ensure that rural students can enjoy the same educational resources as urban students. In addition, the government and education departments should increase investment in education in rural areas, especially in artificial intelligence education and digital literacy training, to enhance the technical contact opportunities and learning support of rural students.

Gender inclusion

Although this study did not find significant gender differences in AI literacy, male students were more prominent in some thinking dimensions (such as algorithmic thinking and critical thinking). This may be related to traditional gender stereotypes and gender differences in STEM education. A meta-analysis study found that K-12 students have gender differences in computational thinking ability, emphasizing the need to promote gender equality in curriculum design45. Therefore, in curriculum design and teaching practice, gender inclusion should be advocated and gender bias should be eliminated, especially in the fields of computer science and artificial intelligence. By setting up gender equality case analysis and cooperation projects, we can encourage girls to actively participate in the study of technical courses, provide more opportunities for display and exercise, and help girls improve their self-confidence in logical thinking and algorithm application.

Evaluation system

Multidimensional evaluation

The cultivation of artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking involves the improvement of multi-dimensional ability. Therefore, when evaluating student’s learning effects, multi-dimensional evaluation methods should be adopted, covering multiple dimensions such as behavior, cognition, emotion and interaction. We should not only pay attention to student’s mastery of technical skills, but also evaluate their high-level abilities such as innovative thinking, teamwork ability and understanding of artificial intelligence ethics. Through comprehensive evaluation, it can fully reflect student’s learning effectiveness, provide more accurate feedback for educators, and help them adjust teaching strategies and contents.

Dynamic tracking

In order to better monitor student’s progress in artificial intelligence literacy and computational thinking training, it is recommended to establish a dynamic tracking mechanism. Through regular learning assessments, project reports and practical activities, we can keep abreast of student’s learning status and ability improvement. In addition, big data analysis and AI tools can be used to accurately track student’s learning trajectories, identify weak links in the learning process, and conduct targeted interventions. This dynamic tracking not only helps to adjust the teaching plan in time, but also effectively motivates students to maintain continuous interest and motivation in the learning process.

Discussion

This study set out to investigate the complex interrelationships between AI tool usage, AI literacy, and computational thinking among Chinese university students from diverse disciplinary backgrounds. Guided by an integrated theoretical framework and a set of specific research questions, the findings offer nuanced insights into how these competencies develop and interact. The following discussion directly addresses each research question in sequence, synthesizing key results, interpreting their significance in light of existing literature and effect sizes, acknowledging limitations, and deriving targeted educational implications.

Addressing research question 1: Levels and group differences in AIL and CT