Abstract

The question remains how to integrate the core service proposals within a smart tourism platform setting for further facilitating tourist value co-creation behaviours in sustainable ways. This paper investigates the paradigm of smart tourism service (STS) platforms within the context of an ecosystem space. It conceptualizes concepts by laying a reasonable theoretical foundation (service-dominant logic) and proposing a scale for smart services. Applying sequential mixed methods to an exploratory research design, with seven interlocking stages and data from Fuzzy Delphi experts and tourist surveys in Taipei City, a smart city in Taiwan, this paper proposes a second-order scale with six dimensions, comprising smart services of attractions, transportation, accommodation, diet, purchase, and payment. The final 32-item STS scale is thoroughly developed and subsequently validated in different contexts (i.e. travellers in different phases of travel, pre-travel and during the trip, respectively). The scale significantly reveals the tourist-operated technologies for the provision of STS, determining the development of conceptual STS platforms in this paper. Next, the platforms disclose the locus between ICT functions, information-related services, tourist applications and behaviours, and sustainable value co-creation. The potential path of “STS → behaviour → sustainable value co-creation” explored herein is helpful for illustrating the conceptualization of STS platforms. Moreover, predictions from the platforms of tourists’ smart behaviours make it practically relevant in assessing demands about smart services for tourism. In the end, this paper describes the theoretical implications and managerial implications for tourism practitioners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Smart tourism service (hereinafter referred to as STS) derives from “smart system” initiatives with specific applications focusing on the tourism sector or destinations (Xiang et al., 2021). The goal of an STS system is to integrate convenience with accuracy, through an easy-to-access platform in the context of technological advancement (Gretzel et al., 2015b). Thus, an STS platform (e.g., smart travel mobile APPs or websites) has been used to describe a software platform that allows tourists to integrate service proposals in a unified smart environment, with an improved user experience thanks to travel information in relation to routes and their status (Choe and Fesenmaier, 2017). The platform has made it easier for tourists to plan their trips as decision support, and for practitioners, it is extensible to manage additional rental and booking services relevant to tourism. In other words, such a platform combines tourist-oriented services and management, emphasizing the importance of providing information to tourists through a technological application (Li et al., 2017).

A smart system emphasizes the contributions to connect a series of online reservations and preferential services in a destination among sectors such as attractions (Wang et al., 2016), transportation (Gonzalez et al., 2020; Naik et al., 2019), accommodation (Stankova et al., 2019), diet (Okumus et al., 2016, 2018), and purchase (Flavián et al., 2020). In this regard, an STS platform dedicates to developing interactive services which help to interconnect local organizations as well as tourists for access to quick service delivery. The platform should satisfy the personalized needs of tourists through a synergy of tourism administration representatives and service providers (Gretzel et al., 2015c). Tourists can therefore experience a new way of information-searching and enjoy visitor services, and they can even have opportunities to exhibit their value co-creation behaviours through the process of interaction with other stakeholders (i.e. firms, governments, and intermediaries) in the context of a smart tourism ecosystem. During the process, tourists actively participate with service providers and cooperate in co-creating their own involvements and sharing experiences, which directly leads to innovation (Gretzel et al., 2015b). While the sustainability in technology-denominated services has become crucial in tourism research (Wang et al., 2020), emphases on the tourist value co-creation process and behaviours, in terms of economic, sociocultural and environmental sustainability, have also increased (Bhuiyan et al., 2022).

To date, few studies have systematically explored the exact framework of an STS platform, leading its precise composition unclear (Ye et al., 2020). Some studies explain that the delivery of technology-denominated services in an efficient manner can be ensured by creating a chain in the tourism industry (e.g. Bhuiyan et al., 2022; Boes et al., 2016; Gretzel et al., 2015b). However, such specific sector studies cannot be used for an aggregate perspective. Particularly, STS is attributed to the aggregate service from the tourism sector in the groundwork for the integration of information service and technology (Li et al., 2017). The tourism sector studied without comprehensiveness results in the limited proposed measures of STS. Moreover, the feedback relationship between tourist value co-creation behaviours and service providers needs to be further explained. A smart ecosystem is an environment of smart platforms that together achieve a single purpose: to deliver smart service, leading to tourism experience and value co-creation (Gretzel et al., 2015a). Therefore, how to integrate the core service measures so that tourists can realize the functionality and convenience of STS is quite important within a smart tourism platform setting (Choe and Fesenmaier, 2017).

To that end, one needs to recognize the fundamental sectors involved in a smart tourism ecosystem, and a need also exists to unveil the key services of smart tourism through exploring the tourism elements-based measures, before promoting the conceptualization of STS platforms. This paper aims to develop the conceptual framework of an STS platform within an ecosystem by proposing an STS scale from an integrative perspective to holistically measure individual sector settings. The STS scale herein may be unique, due to the scale explored for outlining tourist demands by examining smart service measures across the phase of travel. Based on service-dominant (S-D) logic, a functioning service ecosystem is seen as a major prerequisite for enabling the co-creation of customer experiences (Anttiroiko et al., 2014; Vargo and Lusch, 2016). Thus, tourist value co-creation behaviours can also be observed from service measures applied in the ecosystem.

In this paper, a conceptual framework of an STS platform is developed through exploring emergent and potential smart service measures. Therefore, it is an exploratory attempt to integrate a range of smart service providers and constitute a smart tourism ecosystem. The locus of value co-creation between tourists and service providers is formed based on tourist behaviours in the application of smart services (Edeh et al., 2022). In a literature review, this paper first illustrates the nature of STS and the relationship among S-D logic, a smart tourism ecosystem, and tourist value co-creation behaviours. Secondly, the fundamental service elements of smart tourism are provided through a holistic view of sectors in an ecosystem, and then the conceptual base of an STS platform is proposed. As to the research methods, this paper reports a series of studies to explore the STS scale and assess the new scale’s reliability and validity. In terms of discussions, the conceptual framework of an STS platform is logically deducted from the scale that highly correlates with key technological-based characteristics. The sustainable value co-creation from tourist behaviours is also identified. Finally, in the conclusion section, both theoretical and managerial implications are provided.

The nature of smart tourism services

Smart tourism refers to the provision of STS for tourists through Internet devices on mobile devices combined with the evolution of information and communication technologies (ICTs), as well as timely access to tourism information and the convenient use of various travel methods (Xiao et al., 2019). Focusing on the individual personal experiences of tourists, smart tourism attempts to integrate high-quality services at the industry level and meets the growth of tourists’ needs (Gretzel et al., 2015c). The tourism ecosystem will be able to obtain and use relevant tourist information in a timely manner to realize intelligent service and business management. Therefore, STS is empowered through the connection of smart technology, smart tourism experiences, and smart business ecosystems (Gretzel et al., 2015b). Objectives include consumers (tourists), industry (tourism service providers), and the government (local public tourism agencies).

On one hand, STS refers to Smart Technology, which is a kind of ICT-supported integration of multiple tourism factors through intelligent connectivity (Jovicic, 2019). Within a smart tourism setting, such technologies provide tourists and service providers with actionable data, improved support for decision-makers, and increased mobility, all leading to more enjoyable tourism experiences (Cimbaljević et al., 2019). Moreover, sensors and mobile devices, the core technologies of smart tourism, establish environments full of real-time data that help to anticipate tourists’ needs in ways that enhance their tourism experiences (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015; Gretzel et al., 2015a).

A Smart Tourism Experience specifically emphasizes a technology-mediated experience that requires service providers to personalize services by integrating context-awareness data from real-time monitoring (Femenia-Serra and Neuhofer, 2018). Thus, technology is an effective instrument to create and reinforce the tourism experience by providing services of information collection, ubiquitous connectedness, and real-time synchronization to facilitate interaction with the environment (Neuhofer et al., 2015). Smart tourists use technologies, such as wearable sensors to help them self-manage their experiences in an active and engaged way that includes both receiving updates and contributing through self-creation (e.g. uploading pictures) (Femenia-Serra and Neuhofer, 2018).

A Smart Business Ecosystem applies ICT with access to communication networks so as to deliver smart services. The business ecosystem of smart tourism consists of a network of interlinked stakeholders that dynamically interact with each other in a destination. Advancement in technology have digitalized the core business process to help the public and the private sectors to compete and collaborate on available resources, co-create, and jointly adapt to external disruptions (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015; Dong et al., 2020). In tourism, the smart business ecosystem creates value through the co-creation process by applying smart tourism tools, such as online platforms, devices, and social media (Bhuiyan et al., 2022; Gretzel et al., 2015b). Artificial intelligence acts as a disruptive technology that service providers cannot ignore. As a result, the smart tourism ecosystem needs to connect with the smart applications of tourism, technology, and destination (Gretzel et al., 2015c).

Thus, STS relies on three phases in processing information and resources: collection, exchange, integration and intelligent use (Neuhofer et al., 2015). Taking advantage of technology, this kind of service creates an interaction field for tourists to obtain information value by experiencing the smart destination (Ingram et al., 2017). In this way, tourist experience customized services can be provided through the ubiquitous flow of information. Value co-creation can also be possible when direct interaction happens between the service provider and the tourist (Zine et al., 2014).

The relationship among service-dominant (S-D) logic, smart tourism ecosystem, and tourist value co-creation behaviours

S-D logic can serve as the theoretical underpinnings for smart tourism firms to develop and manage business models that obtain a competitive advantage over time (Schmidt-Rauch and Schwabe, 2014). Smart tourism’s emphasis on co-creation fits well into S-D logic (Vargo and Lusch, 2017). First, S-D logic proposes that service provision, value co-creation and value realization take place within networks of actors, representing service-for-service exchange and dynamic processes. Second, the connections of network actors help build service provisions while also boosting resource integration. Finally, consumers experience individual well-being through collaborative activities that lead to value co-creation.

Service ecosystem thinking thus implies a firm’s S-D logic. The service ecosystem is made up of systems of resources that integrate actors through institutions and technologies, co-producing and exchanging service offerings and resources and then co-creating value (Vargo and Lusch, 2016). This corresponds to the notion of dynamically interconnected stakeholders in a smart tourism ecosystem (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015). The interconnection is formed for producing tourism experience through human organizations, technology, shared information and services and resources exchange, on the basis of pre-delivery, delivery and post-delivery experiences. Tourism firms have to collaborate with stakeholders beyond their organizational borders in order to source and exchange resources for value co-creation. Moreover, smart technologies and devices enable firms to develop such dynamic connections and networks with others. Firms can open up communication channels for tourism activities and tourists through mobile technology for mutual value creation and network relationship value (Schmidt-Rauch and Schwabe, 2014).

In this vein, a smart tourism ecosystem is a platform for creating, managing and delivering touristic services via technological advancement which leads to information sharing and value creation (Gretzel et al., 2015b). Firms can co-create value and network relationship value through interaction and reciprocity with tourists through tourism activities, thereby forming a cycle of high-quality tourism. Tourists’ value creation process can be ensured through the formation of a smart tourism ecosystem, in which they can have technology-mediated tourism experiences of personalization, context awareness, and real-time monitoring before, during, and after a trip (Bhuiyan et al., 2022; Neuhofer et al., 2015). Further, sustainability can be created in the value co-creation process (Wang et al., 2020), while focusing on technology-denominated services (Dong et al., 2020). Tourist value co-creation behaviours involve three aspects of advantages of sustainability: economy, socio-culture, and the environment. Therefore, a prerequisite to value co-created behaviours is a functioning smart tourism ecosystem (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015), and firms and tourists equally play their roles in the creation of sustainable value (Bhuiyan et al., 2022). In Fig. 1, this paper proposes how STS fits into the broader conceptual domains of the relationship among S-D logic, smart tourism ecosystems, and tourist value co-creation behaviours.

The S-D logic perspective can be applied to illustrate how the service principle is focused on the smart tourism ecosystem. The ecosystem is constituted of six tourism service elements: attraction, transportation, accommodation, diet, and purchase. Based on the collaboration and resource exchange among tourism service providers, they can enhance tourists’ value co-creation behaviours and then sustainability.

Fundamental service elements in a smart tourism ecosystem

The prime service elements of an ecosystem are service providers and the technologies, platforms, NGOs, and companies from other industries that support the services (Gretzel et al., 2015b). In a smart tourism ecosystem, firms provide smart services by adopting open information systems and technological platforms, as they enable firms to manage their business models in a dynamic way. Therefore, the firms seeking to provide tourists with all-rounded innovative service options have to consider the use of intangible resources (data, technology, infrastructure) in a smart tourism environment (Barile et al., 2017), so as to optimize tourist experiences in the travel process. As Fig. 1 shows, to meet the needs of tourists, the prime service elements of smart tourism comprise attraction, transportation, accommodation, and diet and purchase in firm collaboration, and can serve as the potential dimensions of an STS scale (see Table 1).

Smart attraction services imply the interconnections between attractions and multiple stakeholders through dynamic platforms with information-intensive communication flows. These dynamic connections associated with tourism information realize instant services of free information, tour guide, transport, and transactions, and create an actual tourism experience while improving tourism resource management, thus contributing to the decision support system of the stakeholders (Jovicic, 2019; Wang et al., 2016). To that end, the ICTs are integrated into physical infrastructure, thereby deriving environmental conditions such as technological competence, eco-efficiency, and innovation for smart attraction services (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015).

The essence of smart transportation services lies in an integrated application of technology and management in transportation systems. The integration is meant to enable tourists to be better informed and use the transport network in a safer and “smarter” way (Lin et al., 2019). The establishment of smart transportation serves as real-time location-based information, seamless public transport, and the provision of navigation and parking. Tourists can easily acquire route plans, means of transportation, safety, parking, traffic data and fuel consumption (Siuhi and Mwakalonge, 2016), relying on the intelligent transportation network in a city (Gonzalez et al., 2020; Naik et al., 2019).

ICT applications in smart accommodation services (Stankova et al., 2019) enable hotels to (1) possess a set of well-established intelligent systems, which can realize the informatization of hotel management through digitalization and networking; (2) satisfy tourists’ demands, optimize hotel management, and innovate service; (3) materialize the sharing and effective use of the hotels and social resources. ICT will contribute to creating environments where hotels can interact with guests, such as social network reviews (Xiang et al., 2017), communications (Kamboj and Gupta, 2020), and transactions (Neuhofer et al., 2015), and optimize the control of room service (Stankova et al., 2019). It has become a new business opportunity derived from the intellectualization of hotels to make use of smart services to increase sales (Buhalis and Leung, 2018).

Smart diet services also derive from a high-end system design that incorporates ICT and restaurant management to provide automatic operation for catering organizations. Smart diet services provide tourists with timely, correct and valuable information through mobile technologies (Okumus et al., 2018), which help them make more sensible decisions when ordering food. This also has a positive impact on their ordering behaviours (Sarcona et al., 2017). Moreover, low labor status can be achieved in the process of diet services through smart systems, thereby slashing the labor cost and improving the efficiency of meal delivery while saving customers’ dining time (Okumus et al., 2016).

The backdrop of smart purchase services is related to the consumption environment of e-commerce and extended to that of m-commerce credited to ICT development (Alqatan et al., 2011). Due to their use of mobile devices, consumers can place orders instantly; what they have to think about is whether and what to buy and how to pay instead of when and where to buy (Flavián et al., 2020). Tourists are provided with asynchronous or one-to-many information exchange platforms which influence their purchase decisions (Xiang et al., 2017). To put it in another way, ICT realizes more frequent interactions between tourists and social networks, which not only facilitates information searching but also changes tourists’ buying habits.

The conceptual base of smart tourism service platforms

A smart tourism ecosystem helps to build a platform that provides service data and infrastructure to tourists (Gretzel et al., 2015a). The platform, therefore, must be able to cater to functions not only for tourists but also for managers, in order to provide extensive and customizable tourism services while management efficiency is increased. The STS platform in the ecosystem is ICT-integrated, with the Internet of Things (IoT) running on cloud computing services employing artificial intelligence all working together to forecast demand, increase efficiency, implement process automation, and improve value co-creation (Cimbaljević et al., 2019; Jovicic, 2019).

With a focus on tourists as the users of an STS platform, the platform aims to support tourists by (1) collecting and anticipating tourist demands, and making recommendations toward travel consumption decisions (Choe and Fesenmaier, 2017); (2) formulating tourists’ on-site experiences by integrating technological and information resources to offer real-time data for context awareness and personalization (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015; Neuhofer et al., 2015); (3) offering accurate information to conveniently grasp and process and accessing service plans (Li et al., 2017); (4) co-creating the value of smartness by delivering intelligent touristic services through smart technology interactions and a wider smart ecosystem (Gretzel et al., 2015c).

As a result, STS platforms emphasize meeting tourist needs through inclusive information that is promptly and conveniently collected and processed (Gretzel et al., 2015c). Tourists can access tourism information through the platform and promptly arrange and adjust their travel plans. Moreover, this enables tourists to upload feedback to the system and share their travel experiences (Choe and Fesenmaier, 2017). Thus, the span of online information services is across the phases of before, during, and after the travel (Li et al., 2017).

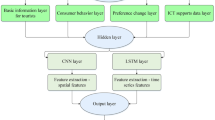

Tourists can apply a full range of information services to conduct the reservation and transaction of tourist elements as well as other sales options, all of which have played prominent roles in the safety, convenience and mobile search of tourism (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015). The STS platform integrates a wide range of tourist-operated technologies and systems that create augmented realities in direct support of tourism so that it helps tourists in their decision-making behaviours (Lamsfus et al., 2014). In this respect, this paper proposes that a meaningful platform is seen as information delivered, function catered, context applied, and tourist behaviour supported (Fig. 2).

A meaningful smart service platform must support tourists firstly through information collection and delivery. Subsequently, functions catered by the platform can offer tourists to have customized services, and tourists can experience and apply the service contexts created. Finally, the platform can help tourists in their decision-making behaviours.

Methods

Research design

Based on the purpose of this paper, it was necessary to go through the processes of developing a new validated scale before constructing the conceptual framework of an STS platform. Thus, an exploratory sequential mixed-method design was employed to develop and validate a survey instrument. This paper employed a multi-stage recursive psychometric process with three studies made up of seven stages.

Study 1—qualitative study

Stage 1: Item generation

The established scale development procedures included item generation, adjustment, and purification (Table 2). The generation of items followed two steps, reviewing literature and qualitative data collection and analysis. Saturation was reached, with data from two sources repeating previous data.

Systematic literature review

A review of related studies formed a collection of possible items. This data collection was repeated twice to assure any related smart tourism published papers were included. First, this paper collected peer-reviewed articles in Scopus, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science. This determined three search criteria common to the topic that was next used to search for relevant items. First, the term “smart service” was combined with “technology,” “tourism,” “tourist,” “travel,” “transportation,” “hotel,” “restaurant,” “purchase” to formulate keywords. Second, published manuscripts included in the search were determined by review of the title, abstract, or executive summary. Published papers were from the time frame of 2000–2020. Third, this paper included only English full-length papers appearing in the Science Citation or Social Science Citation Indexes.

Next, the collection results and applied the same criteria within the mentioned smart tourism distribution journals in Mehraliyev, Choi, and Köseoglu (2019) and Ye et al. (2020) to check for missing articles. Researchers reviewed the articles independently and then together with the exclusion of duplicate articles or papers not directly related to STS.

Expert qualitative interviews

The Fuzzy Delphi Method for expert-based data collection was adapted to guide the measurement of item identification. The expert comments came from a two-round Delphi questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed semi-structurally and it asked experts to subjectively assess the items according to the foregoing tourist elements. The first round of questionnaire design was made up of two sections. Section A addressed the smart service items in each tourist element. Section B addressed questions about the demographic characteristics of the experts (i.e. gender, age, education, institution, title, and seniority). The questionnaire’s content validity was reviewed by two additional faculty members with expertise in qualitative research.

At the end of each item in section A, the experts were given space to make supplementary explanations or add new items, expecting to make up for the incompleteness of the initial item list. Particularly, each item was followed by noun explanations and case references to ensure the consistency of meanings of all experts to each item, thereby obtaining the most appropriate results. Each item was assessed on its importance on a five-point Likert-type scale with anchors that ranged from 1 (not very important) to 5 (very important). The second round of questionnaire design was similar with the prior one, but it included the first-round statistical analyses for the experts’ reference in order to converge the still divergent views.

A purposive sampling of two groups (i.e. 11 tourist experts and 6 Internet and e-commerce experts) provided opinions related to the topic. Respondents’ verbal consent was sought for scheduled interviews. The interviews were mostly held online, lasting from 30 to 50 min. Respondent demographics can be seen in Table 3.

Stage 2: Item purification

This stage comprised expert review and exploratory factor analysis of the measurement items to purify the pool of questions. The details of expert reviews are explained in this section.

Expert review

Experts in the field reviewed the draft items, checking content validity. The items were rated by clarity, readability, redundancy, representativeness, and suitability. The items were next compared to and combined with other items derived earlier in the first round. A consensus was reached among the experts.

Study 2—Quantitative study

Stage 3: Dimensionality determination of the scale

Data collection instruments and procedures

The survey data was collected to explore the dimensional structure of the STS scale. Taipei City, an internationally awarded smart city, has taken the lead among other major cities in the Asia-Pacific region. Given that smart tourism and smart city complement each other (Hunter et al., 2015), Taipei City was selected as the survey site of smart-city destination in this paper, with the subjects being the tourists in various tourist attractions of Taipei.

The survey was structured into six sections. Sections A–E contained views on elements of STS in attractions, transportation, accommodation, diet, and purchase. These sections sought to measure the tourists’ demands on each element of smart services on a Likert’s 5-point scale, where 1 meant not agree at all and 5 represented very agree. As to specific services, respondents were asked to rate their demands using the measurement items drawn from Study 1. Section F measured the respondents’ socio-demographic and travel characteristics.

In this pre-test of the survey questionnaire, 90 tourists to Taipei took part. Useful data were collected, using the convenience sampling technique. The respondents were approached conveniently at the visitor recreation areas of the most visited attractions. For those who visited the attractions in groups, two people on average were chosen to participate in the study. This approach guarded against potential group bias. To ensure the respondents fill in information accurately, the research assistants checked the returned questionnaires on-site for sample validity, and this resulted in the collection of 379 valid questionnaires. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was then conducted via SPSS 22.0 to explore the dimensional structure of the measure and to remove poorly fitted items.

Study 3—Quantitative study

Stage 4: Scale validation

Data collection

The second set of 815 completed questionnaires was used to confirm and refine the structural validity of the six-factor solution extracted in the EFA, using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS. The data collection procedure in this stage was similar to that for Stage 2 described earlier, except that the data were disproportionately collected from Taipei City and online. This means that a pre-traveller sample was included in this stage.

Collecting part of the validation data was meant to minimize the biases that characterize data from the same destination. Moreover, pre-traveller data was included in order to lower bias from respondents who were already travelling. The sample frame of pre-travellers is an unclear population that is challenging to recruit. Thus, snowball sampling was used. Travel agencies assisted in distributing the survey invitation with a link to the online questionnaire to clients who were planning their trips for the year (in Taipei). These contacts were then asked to forward invitations to their friends and relatives.

The observations randomly comprised two sample groups: calibration (n = 410) and validation sample (n = 405). As a rule of thumb, at the very least, an item should correspond to 10 sample cases. Thus, for a minimum response requested for 32 items based on EFA, the respondents in each group were a satisfactorily conservative sample size for the analysis. The characteristics of the sample in this stage were compared with those of Study 2 (Table 6).

Stage 5: Common method biases

Both pre and post-techniques were employed to minimize and check the presence of common method biases in the models. Experts reviewed potential items. Harman’s single-factor test was next used with items constrained to loading one factor at a time across EFA and CFA stages.

Stage 6: Model invariance test

A test of measurement model invariance was used in testing six dimensions of the STS scale in different phases of travel, pre-travel and during the trip. This was to assess the representativeness and generalizability of the scale across various travel phases.

Stage 7: Nomological and construct validity

Testing nomological and construct validity, a second-order structural equation was used. This approach tested the predictive power of the STS scale dimensions.

Results

Study 1—Qualitative study

Stage 1: Item generation

Systematic literature reviews

83 STS articles were confirmed (Table 4). Relevant items were collected in a Microsoft Excel sheet with a pool of 68.

Expert qualitative interviews

Ultimately, the consensus of the expert group on the dimensions of STS was reached, including the fitness assessment between dimensions and items and the representativeness of items for dimensions.

In the first round, this paper used geometric mean (G) and quartile deviation (Q) to determine the consensus of expert opinions on the initial 68 items, as well as the overall assessment of the importance of the items. The results were adopted to determine which items should be investigated again in the next round. This resulted in 8 items reaching a high consensus (Q ≤ 0.5) with 60 remaining items to proceed to the second-round expert reviews.

In the second round, a failure to meet the standard of “important” occurred when (1) the G value was lower than the threshold value of S = 3.5 (G < 3.5) and (2) if first quartile (Q1) < 3 and third quartile (Q3) < 4, the item was removed. Additionally, Kruskal–Wallis Chi-Square Tests were carried out via SPSS 22.0 to test the importance of the remaining items. The significant level of the item test suggested to reject H, indicating a wide gap in the cognitive outcomes of the two groups of experts for the item. Then, such an item was removed. The results of this round came with the consensus of all experts, which means that there is no need to carry out the third round, and 10 items were removed from the second analysis.

Stage 2: Item purification

Expert reviews

According to the review results, 10 items were removed, and 12 items were combined into 6 due to similarities. Furthermore, 2 items were added. By doing so, 54 items were identified. The items were then re-worded with the help of topic words/phrases (Table 5) to match the context of STS. According to the two-round Fuzzy Delphi, the initial pool of 68 items was trimmed to 44 and they were retained for questionnaire design in the quantitative stage.

Study 2—Quantitative study

Stage 3: Dimensionality determination of the scale

Data analysis

In the pre-test phase, Chrobach’s α values (internal consistency criterion) of all items were >0.9. However, one item’s critical ratio value (reliability analysis) was not significant, and the values for corrected item-to-total correlations of 4 items were <0.3. Therefore, 5 items must be deleted, and 39 items were retained for the formal test stage.

Detailed characteristics of the 379 respondents are found in Table 6. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO = 0.95) measure of sampling adequacy (≥ 0.80) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ2 = 8692.21; P < 0.001) showed that the 379 observations were suitable for EFA. The principal components analysis was adopted to calculate the communalities of the items, and the rotation method used was varimax employing the orthogonal rotation. Eigenvalue >1 was the criteria used for determining the number of factors extracted. The additional rule was that each dimension must have at least three items. Finally, 7 items were dropped for having item-to-dimension loadings <0.50 and inter-dimension cross-loading >0.5.

In all, six unique dimensions with 32 well-fitted underlying items were extracted from the EFA, which explained approximately 70 percent of the variance in STS. The Cronbach’s alpha score for each factor was higher than 0.70, suggesting a satisfactory inter-item-dimension convergent validity. Given each dimension’s item content, they were labelled smart attraction services, smart transportation services, smart accommodation services, smart diet services, smart purchase services, and smart payment services (a new dimension extracted). Details of the percentage of variance explained by each dimension and corresponding Eigenvalue are presented in Table 7.

Study 3—Quantitative study

Stage 4: Scale validation

Data analysis

Results from CFA showed all items exhibited statistically significant (p < 0.001) coefficients for calibration and validation models, exhibiting unidimensionality across all dimensions. Composite reliability scores exceeded 0.80 for all dimensions, evidencing good internal consistency (Table 8). The overall model fits indices for both the calibration (\(\chi ^{{{\mathrm{2}}}}/{\rm {d}}f\) = 2.67, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05) and validation models (\(\chi ^{{{\mathrm{2}}}}/{\rm {d}}f\)=2.97, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05) indicated that they were optimally fitted. Moreover, both second-order models have proved to well-replace the first-order models (\(\chi _{{{\mathrm{1}}}}^{{{\mathrm{2}}}}/\chi _2^2\) = 0.97; 0.96) as the framework for the STS scale (Table 9). Table 10 shows good discriminant validity with each latent dimension sharing more variance with its observed items than with other dimensions.

Stage 5: Common method biases

Results showed any single factor did not well capture the covariance of the items. The percentage of variance explained was 44% and 43%, respectively. Thus, method bias was determined to be minimal and would not risk the conclusions drawn from the study.

Stage 6: Model invariance test

Table 11 shows that both constrained and unconstrained models for the two phases of travel do not significantly vary. This result supports model validity to assess tourists’ demands of STS, and the phase of the trip made no difference.

Stage 7: Nomological and construct validity

All indices exhibited second-order factor structure with the data fitting the model well, see Table 8. The dimensions demonstrate the structural validity of the hierarchical CFA. Squared multiple correlations revealing each dimension explained nearly more than 50 percent of the variance, see Fig. 3. Results suggest all dimensions are indeed important to tourists.

Discussion

The seven stages conducted converge with evidence of a six-dimensional STS scale, suggesting that these dimensions are the core of the STS that tourists experience. The tourism sectors represented here are attractions, transportation, accommodation, diet and retail, and the service providers include travel agents and tour operators, hotels, restaurants, local communities and organizations, and the government agencies that cooperate with these sectors. The service providers in the constituted smart tourism ecosystem can benefit themselves and each other with economic, socio-cultural, and environmental sustainability through the process of co-creating value of experience with tourists (Bhuiyan et al., 2022). The STS scale provides the applications of smart service measures that will influence tourists’ behaviours in each stage of travel (before, during, and after a trip), which is conducive to sustainable value co-creation. The findings of tourist value co-creation behaviours respond to Bhuiyan et al.’s (2022) exposition on sustainability. In addition, the STS scale constructs a more comprehensive smart tourism ecosystem and more specific, relevant measures. It provides a well underpinning for the establishment of the conceptual framework of the STS platform. The platform can therefore propose the locus of the value co-creation process between tourists and service providers. The findings from the STS scale are discussed as the followings.

The first dimension, smart attraction services, verify that intelligent service perspectives are applicable across all phases of travel (Xiang et al., 2015). It proves that ICTs combined with the infrastructure (software and hardware) of scenic spots are conducive to creating and meeting tourists’ needs for tourism experiences, as well as linking with the service environment of other tourism elements. (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015). Specifically, before a trip real-time information access means that tourists would like to use free attraction information to identify problems and develop potential solutions to address them (Jovicic 2019), mainly involving reservations, the weather, tourist flows, and queuing time. During trips, an effective smart guide system is required and location-based services (e.g. near-field communications, beacons or augmented reality) are helpful for providing dynamic guidance of attractions. Moreover, tourists expect to establish a personalized itinerary planning system based on tourism information databases, and they share their plans via mobile devices for others to download them. Interactive multimedia systems (e.g. augmented/virtual reality somatosensory facilities) are also mentioned as useful for creating smart experiences that tourists would like to share after the trip.

The second dimension, smart transportation services, denotes two situations of tourists’ demands to find necessary transportation services and/or related information. For self-transport travel, three measurement items support Lin et al.’s (2019) findings that a location-based service scheme should include navigation systems and real-time information on traffic and parking. For non-self-transport travel, two items also reflect the necessity of public transport information and intelligent transport scheduling systems (e.g. shuttle buses, electric scooters). Intelligent transportation systems (e.g. telematics) can help tourists make better use of the transportation network. However, the items also reinforce Gonzalez et al. (2020) and Naik et al.’s (2019) argument that access to smart transportation remains a significant challenge with regard to infrastructure in a city.

Both the third and fourth dimensions, smart accommodation and diet services, are associated with a perceived service of hospitality during a trip, with a focus on intelligent management. The findings support Cimbaljević et al.’s (2019) assertion that businesses must respond to the respondents’ request to establish an automatic operation system to substantially improve operational efficiency and reduce mistakes. First, self-service counters for instant registration and self-service ordering systems are applied as an integrated tools for practitioners’ marketing and operation. Second, mobile booking and ordering systems emphasize mobility and convenience. Tourists can make room/meal reservations that match the arrival time and location through the systems in advance.

Third, smart room access control and cabinet systems are installed to satisfy tourists’ safety demands. Guest room privacy and security is a long-standing issue but more palpable today, which calls for the active practitioner-tourist co-creation of solutions for tourists (Stankova et al., 2019). Four, the practitioners may provide and optimize the entire service process to meeting tourists’ meal demands. Such include efficient tourist guidance, pre-order and queue services before arrival, service request systems during dining, and cloud service systems (platforms/software/infrastructure/technologies) for tourists to share their opinions after their meals. The measurement items herein prompt practitioners to connect with smart tourism networks, sensors and extractors in the smart hospitality ecosystem, in order to collect and analyse the big data from tourist reservation information and thereby enhancing revenue management performances (Buhalis and Leung, 2018).

While the above four dimensions of the scale are conceptually unique, the facets of the smart purchase and payment service dimensions share some commonalities with the general m-commerce-related concepts (i.e. electron, convenience, and mobility) facilitating tourists to choose tourism services (Alqatan et al., 2011). Despite that, the differences in the measurement items between these two dimensions can still be clearly identified. The items of smart purchase services are measured from a utility perspective, while those of smart payment services are mainly based on the payment method.

Seven measurement items of smart purchase services involve tourist engagement in information gathering, planning, comparison, and purchase experiences. From a utility perspective, tourists are willing to invest time and effort in searching for and using promotion-related information to save costs. Tourists emphasize smart and transactional value because they can achieve time and/or effort savings by conveniently using online systems, or because they feel pleasure that they are making the right purchases (Flavián et al., 2020). Therefore, the findings comply with those of Xiang et al. (2017) who believe that tourists would like to engage in smart purchases only when the products purchased on the Internet can match their demands and provide good value for the money spent.

Smart payment systems are those that allow consumers to pay their bills via smart platforms rather than cash, check, or debit card. With this technology, payment services operating under financial regulations are performed via mobile devices, and the type of payment includes mobile wallets, credit cards, carrier billing, etc. (Banerjee and Wigginton, 2015). Tourists can therefore enjoy the benefits of convenience, lower payments, and safe and secure payments. However, the current literature provides few explanations for smart payment services by tourists. Four measurement items of smart payment services preliminarily respond to Gretzel et al.’s (2015b) findings that tourists can pay for a range of services using smart devices as a viable payment option.

Essentially, the proposed STS scale integrates the fundamental tourism elements in a smart tourism ecosystem, lays a reasonable theoretical foundation (S-D logic), and provides a practical assessment tool for smart services. Moreover, the measurement items have explained the sustainability for tourists in terms of economy (i.e., reducing travelling costs, increasing decision-making efficiency, and avoiding unnecessary time wasting), socio-culture (i.e., instant access to information and public facilities, comfort in travelling, and memorable experiences), and the environment (i.e., reducing energy consumption, receiving proper guidance of environmental challenges, and receiving information about the destination’s ecology). The findings imply how tourists create sustainable value-co-created behaviours by experiencing smart service measures.

On the other hand, the scale highlights the complete experience of travel processes, resulting in findings that have relevance for tourism practitioners on several functions regarding smart tourism services. These functions include a collection of tourist demands, pre-travel planning programs, experience creation, convenience and access plans, and value enhancement strategies. By logical deduction, a conceptual framework of the STS platform is constructed (Fig. 4). The broad nature of the platform not only calls for the co-creation of tourist experiences but also represents a comprehensive assessment tool for practitioners in assessing demands about smart tourism services.

On the supply side, a comprehensive structure is represented for practitioners in meeting demands about STS, including the connection of tourist-operated technologies, functions revealed by the ecosystem integrated supply, and information services generated. On the demand side, tourists can create sustainable value-co-created behaviours by experiencing smart service measures. The STS platform discloses the locus of “STS → behaviour → sustainable value co-creation”.

Based on the cooperation between ICTs, the technological-based characteristics of smart service platforms, such as connection between tourism and ICT (Choe and Fesenmaier, 2017), tandem and co-marketing of the tourism industry chain (Li et al., 2017), and tourist data collection and analysis (Gretzel et al., 2015c) will lead a constructed STS platform to create a holistic smart tourism ecosystem. The ecosystem reveals the progress and functions of ICT, which not only strengthens the service capability of information generation but also highlights the service process of information transmission and processing (Gretzel et al., 2015a). The ways of information service systems can better facilitate tourists to apply the STS.

From the system, tourists learn and apply information including weather, queuing time, tourist flow, traffic, parking lots, public transportation, e-maps, hotels, catering and purchase prices. As a result, itinerary planning, reservation, purchasing, payment, and experience sharing will obviously change along with tourist behaviours across the stages of travel. Based on the functions of ICT in STS platforms, the locus between services and behaviours is consistent with Li and Zhang’s (2022) system layers; that is, services, applications, and then users. When customers’ skills and behaviours are transformed into the company’s value creation, the mechanism of co-creation is formulated (Wang et al., 2016). Thus, tourist behaviours can be seen as a supplementary resource to the service provider’s internal value-creating procedures. Tourist-service provider interactions have thus become the locus of value creation (Edeh et al., 2022).

Moreover, with the help of tourist-operated technologies, service providers can obtain and use the information on tourist behaviours, which will support their sustainability in a smart tourism ecosystem. For example, in terms of finances, firms can decrease overlapping tasks, lower marketing costs, and disperse information. In the socio-cultural aspect, they will be able to gain instant access to tourist information and maintain long-lasting customer relationships. As to the environment, firms can save energy and receive proper guidance and information against environmental challenges. In this regard, as active actors of the ecosystem, tourist behaviours contribute to sustainable value co-creation. Finally, the findings respond to Xiang et al.’s (2015) service perspectives that tourist behaviours in the role of creating sustainable value co-creation come across three phases of travel, i.e., pre, during, and post-trips, in particular technology-denominated services.

Conclusion

Academia representatives said that the construction of the STS platform not only has to focus on the investment of information network technology and infrastructure but also needs to consider tourists’ needs from the perspective of tourists and constantly innovate the provision of STS (Li and Zhang, 2022). In this respect, this paper investigates the paradigm of STS platforms within the context of an ecosystem. It conceptualizes the concept by laying a reasonable theoretical foundation (service-dominant logic) and proposes a scale for STS. The scale explores a system’s functional framework in a smart tourism ecosystem for fundamental sectors such as attractions, transportation, accommodation, diet, purchase, and payment. Each of the sectors includes smart service measures preferred by tourists to meet their needs. Based on the scale, the STS platform conceptualized here illustrates how to integrate the core service measures so that tourists can realize the functionality and convenience of STS. Moreover, it explains the value of co-creation feedback to service providers from tourist behviours after applying STS measures and then resulting in sustainability for tourists and service providers. In the end, this paper describes the theoretical implications as well as the managerial implications for tourism practitioners.

Theoretical implications and contributions

More systematic research is still absent from the framework development of STS platforms for smart cities (Ye et al., 2020). This paper bridges the gap by proposing the STS scale from an integrative perspective and further presents the relationship between sustainable value co-creation between tourists and tourism firms. To that end, this paper conducts exploratory sequential mixed methods that include a multi-stage recursive psychometric process with three studies. The findings, from the perspectives of both experts and tourists toward Taipei City, validate the STS scale and realize the contextualization of illustrating the STS platforms. Consequently, this study proposes the theoretical implications and contributions on three aspects of scale construction, sustainable value co-creation, and platform frameworks.

First, the STS scale summarizes the ecosystem of smart tourism in six elements of the industrial chain and also integrates various STS measures, which provided specific theoretical support and scientific basis for the overall development of smart tourism. It is a comprehensive scale proposed for measuring tourists’ demands for smart services in the travel processes, which hitherto was not available in the smart tourism literature. Six tourism elements are revealed which manifest in the form of attractions, transport, housing, food and consumption about travel outcomes, information access, and feeling about service experiences. A series of studies suggests that the scale exhibits satisfactory measurement quality in terms of reliability, construct and nomological validity, and hierarchical factor structure. The primary contribution of the scale lies in an initial attempt to develop an integrative multidimensional hierarchical scale, which is either psychometric, experiential, or combined and should be studied as such. It fills an important gap in the existing literature related to an STS platform.

Second, the provision of STS emphasizes the connection between tourists and service providers and the co-creation of tourist experiences in the smart tourism ecosystem (Gretzel et al., 2015b). Past studies have contributed to the foundation of smart tourism tools used for the connectivity of different tourism stakeholders. This study further provides an overview of STS measures and tourist behaviours in the smart tourism ecosystem and how that facilitates the sustainable co-creation of value. In other words, this study offers insights into the corresponding service items that influence tourist behaviours when the value is co-created, and somehow enhances sustainability for stakeholders. The findings contribute to the integrative approach of sustainable value co-creation through tourist behaviours in different phases of travel. Particularly, the potential path of “STS → behaviour → sustainable value co-creation” explored herein will help researchers and practitioners understand the conceptualization of the STS platform.

Third, the STS platform conceptualized by this paper reliably predicts tourists’ smart service applications of specific sectors and reflects their common behaviours in travel processes. Findings imply that increased demand for smart service is associated with under-experience. This reinforces earlier conclusions that need significantly predict applications and behaviours toward smart tourism. Therefore, the STS platform could be used as an effective medium for identifying inexperienced tourists and their underlying demands. This paper suggests that the STS platform concept has the advantage of being applicable to a wide range of travel-related typologies. Such an approach to STS can better help in identifying tourism antecedents, moderators, and implications.

Managerial implications

This paper proposes an empirical exploration of service platforms for smart tourism that has been usually overlooked. As Fig. 4 shown, the STS platform has a technological base in that firms in a tourism service ecosystem are collaborated through information aggregation, ubiquitous connectedness and real-time synchronization (Neuhofer et al., 2015). Given the functions of this platform, several practical lessons are learned. First, strategies for satisfying needs quantified by the STS scale are more useful if they have a wide scope and cover the six elements, which is useful for tourists to adopt smart tourism behaviours. The practitioners should develop a dedicated smart system, potentially similar to the STS platform, for continuous collection of tourists’ smart service demands for swift satisfaction given that preferences change with time.

Second, the STS platform provides managers with institute-tailored travel planning for tourists during pre-travel consultations. The platforms for tourist preference, accessible, and transparent travel-based information on service designs could be useful in minimizing the gap between expectations and experiences. The demands have to be surrounded with the appropriate tourism information, in support of STS. Ubiquitous web channels, including practitioner’s official or government websites, tourism comparison websites and travel social media, could be leveraged for mass campaigns. The establishment of the STS platform capitalizing on web channels’ ubiquity could be useful in listening to and tactically satisfying tourist demands.

Third, mobility and convenience are positively related to smart service experiences, which denotes that those two are significant incentives for those experiences among the majority of tourists (Buhalis and Amaranggana, 2015). Tourists can rely on the STS platform to solve the concerns that often occur in the travel process, such as difficulty in itinerary planning, lack of local guides, incorrect tourism information, difficulty in booking hotels and restaurants, inconvenience in purchasing and payment, etc. The information service and the mobile reservation and payment via the STS platform that enables tourists to appreciate the necessary service could increase their perceived convenience and stimulate experience before, during and after the travel.

In addition, the STS of the platform should be offered for free (e.g. information sharing) or at discounted rates (e.g. booking fees). Discounted services could be a determinant of smart tourism engagement for tourists as they are often constrained by personal budgets. Travellers like backpackers, for example, place a strong emphasis on travel budgets. For such travellers, reduced costs are very useful. Tourism managers can educate tourists and encourage an emphasis on smart services as one of the components of their travel budgets.

Although tourists may perceive time loss in accessing services, opportunities are provided for recasting the re(design) of practical situations, service processes, and experience creation (Pearce, 2020). These concerns can be thought of by practitioners to manage tourists’ frustration that it is time-wasting to access STS. Applying ICTs to assist practitioners in rapid service integration and innovation and providing joint business consulting and big data analysis would be useful.

Fourth, access services that consumers are unaware they may want, can be communicated through smart service finder pop-ups (or shortcuts). These can direct tourists to appropriate locations. Such a system would enable tourists to explore and identify practitioners that provide all needed services and compare prices for the best deals. More importantly, STS is readily available and accessible in the platforms by improving the forecasting accuracy of services’ demand and supply to minimize or, at best, eliminate errors (Anttiroiko et al., 2014). For example, hotels through their booking data could help travel agencies plan their itineraries by signaling how many travellers from each originating region are likely to be served and for which demands.

Fifth, the more tourists believe that the products, services and information provided by ICTs are reliable and trustworthy, the more value they will create through interactions and service experiences with a destination (Ingram et al., 2017). The strategic implications can be employed by tourism practitioners to enhance service values as those being reliable for tourists to access STS and create their experiences. The STS platform could be useful to introduce managers whose smart services are embraced by tourists and can aid them in selecting tourists to facilitate sustainable value co-creation behaviours. For instance, managers may use the platforms for market segmentation and tourist profiling to gain useful information for maximizing value co-creation behaviours. Tourism practitioners thus are kindly reminded to install and provide focused services by developing cloud technologies, networks, and various tourism application service systems in the current smart tourism trend.

Finally, smart tourism technology is the key factor affecting tourists’ experiences, satisfaction, and revisit intentions (Jeong and Shin, 2020), affecting the development of the tourism economy and society. A real-time tourism service of STS platforms and tourists’ responsiveness to the same give opportunities to tourists to influence other tourists and potential tourists, especially through social connections in an online setting. Tourism practitioners can provide venues for “tourists to share views, preferences, and experiences with others,” as well as allowing for eWOM activity among tourists. Experienced tourists are a more credible voice of the STS. They not only help other tourists recognize their underlying needs but also make others see how the STS can meet those needs, thus blurring the boundaries between a service provider’s role and a tourist’s role.

Limitations and directions for future research

Some limitations are worth acknowledging and should motivate future research into these issues. Though the study took into consideration matters toward a wide range of specific tourism elements, its attempt to propose a generic scale for gauging STS could be an over-universalization of reality. Further smart-service-specific studies are required to validate various aspects of the scale, given that perceptions vary significantly with different smart cities and respondents’ characteristics (Ye et al., 2020).

Future research could also explore the utility of the STS platform among different typologies of tourists, such as backpackers, volunteer tourists, or other tourist groups. This will shape further insights into the antecedents of the platform and especially how it relates to group normative. The platform could also be investigated by utilizing different smart technologies, such as smartphones or other mobile device applications while seeking to identify its moderators (i.e. smart experiences, information exposure, and smart tourism literacy) and outcomes. Besides, it is essential to study how to facilitate sustainable value co-creative services and behaviours through increased interactions between tourists and the STS platform by further utilizing innovative smart technologies. Exploring how the platforms play out during the construction of a smart city, especially its implication for the reception of a potential STS among tourists, would be another exciting avenue of research.

It is essential to note that the stage of travel will likely change tourists’ service demands. Especially, the COVID-19 pandemic-induced health threats have changed tourist behaviour (Abdullah et al., 2020). Future research into the competing STS alternatives to different stages of travel for tourists could provide insights into the potential cross-sectorial integration of STS.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JHJQJD.

References

Abdullah M, Dias C, Muley D, Shahin M (2020) Exploring the impacts of COVID-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Transp Res Interdiscip Perspect 8:100255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2020.100255

Alqatan S, Singh D, Ahmad K (2011) A theoretic discussion of tourism m-commerce. Res J Appl Sci 6(6):366–372. https://doi.org/10.3923/rjasci.2011.366.372

Anttiroiko AV, Valkama P, Bailey SJ (2014) Smart cities in the new service economy: building platforms for smart services. AI Soc 29(3):323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-013-0464-0

Banerjee P, Wigginton C (2015) Smart device, smart pay: taking mobile payments from coffee shops to retail stores. Deloitte University Press

Barile S, Ciasullo MV, Troisi O, Sarno D (2017) The role of technology and institutions in tourism service ecosystems: findings from a case study. TQM J 29(6):811–833. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-06-2017-0068

Bhuiyan KH, Jahan I, Zayed NM, Islam KMA, Suyaiya S, Tkachenko O, Nitsenko V (2022) Smart tourism ecosystem: a new dimension toward sustainable value co-creation. Sustain 14(22):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215043

Boes K, Buhalis D, Inversini A (2016) Smart tourism destinations: ecosystems for tourism destination competitiveness. Int J Tour Cities 2:108–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-12-2015-0032

Buhalis D, Amaranggana A (2015) Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience through personalization of services. In: Tussyadiah I, Inversini A (eds) Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015. Springer, Cham, pp. 377–389

Buhalis D, Foerste M (2015) SoCoMo marketing for travel and tourism: empowering co-creation of value. J Destin Mark Manage 4(3):151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.04.001

Buhalis D, Amaranggana A (2014) Smart tourism destinations. In: Xiang Z, Tussyadiah I (eds) Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014. Springer, Heidelberg, pp. 553–564

Buhalis D, Leung R (2018) Smart hospitality interconnectivity and interoperability towards an ecosystem. Int J Hosp Manag 71:41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.11.011

Choe Y, Fesenmaier DR (2017) The quantified traveler: Implications for smart tourism development. In: Xiang Z, Fesenmaier DR (eds) Analytics in smart tourism design, tourism on the verge. Spring International Publishing, Switzerland, pp. 65–77

Cimbaljević M, Stankov U, Pavluković V (2019) Going beyond the traditional destination competitiveness—reflections on a smart destination in the current research. Curr Issues Tour 22(20):2472–2477. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1529149

Dong X, Liu S, Li H, Yang Z, Liang S, Deng N (2020) Love of nature as a mediator between connectedness to nature and sustainable consumption behavior. J Clean Prod 242:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118451

Edeh FO, Zayed NM, Perevozova I, Kryshtal H, Nitsenko V (2022) Talent management in the hospitality sector: predicting discretionary work behaviour. Adm Sci 12(4):122. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040122

Femenia-Serra F, Neuhofer B (2018) Smart tourism experiences: conceptualisation, key dimensions and research agenda. J Reg Res 42:129–150. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ris:invreg:0386

Flavián C, Gurrea R, Orús C (2020) Combining channels to make smart purchases: the role of webrooming and showrooming. J Retail Consum Serv 52:101923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101923

Gonzalez RA, Ferro RE, Liberona D (2020) Government and governance in intelligent cities, smart transportation study case in Bogotá Colombia. Ain Shams Eng J 11(1):25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2019.05.002

Gretzel U, Koo C, Sigala M, Xiang Z (2015a) Special issue on smart tourism: convergence of information technologies, experiences, and theories. Electron Mark 25(3):175–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0194-x

Gretzel U, Sigala M, Xiang Z, Koo C (2015b) Smart tourism: foundations and developments. Electron Mark 25:179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0196-8

Gretzel U, Werthner H, Koo C, Lamsfus C (2015c) Conceptual foundations for understanding smart tourism ecosystems. Comput Hum Behav 50:558–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.03.043

Ho CI, Lin YC, Yuan YL, Chen MC (2016) Pre-trip tourism information search by smartphones and use of alternative information channels: a conceptual model. Cogent Soc Sci 2(1):1136100. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2015.1136100

Hunter WC, Chung N, Gretzel U, Koo C (2015) Constructivist research in smart tourism. Asia Pac J Inf Syst 25(1):105–120. https://doi.org/10.14329/apjis.2015.25.1.105

Ingram C, Caruana R, McCabe S (2017) PARTicipative inquiry for tourist experience. Ann Tour Res 65:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.04.008

Jeong M, Shin HH (2020) Tourists’ experiences with smart tourism technology at smart destinations and their behavior intentions. J Travel Res 59(8):1464–1477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519883034

Jovicic DZ (2019) From the traditional understanding of tourism destination to the smart tourism destination. Curr Issues Tour 22(3):276–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1313203

Kamboj S, Gupta S (2020) Use of smart phone apps in co-creative hotel service innovation: an evidence from India. Curr Issues Tour 23(3):323–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1513459

Kwok LC, Yu B (2013) Spreading social media messages on Facebook: an analysis of restaurant business-to-consumer communications. Cornell Hosp Q 54(1): 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965512458360

Lamsfus C, Wang D, Alzua-Sorzabal A, Xiang Z (2014) Going mobile defining context for on-the-go travelers. J Travel Res 54(6):691–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514538839

Li Q, Zhang Y (2022) Design and implementation of smart tourism service platform from the perspective of artificial intelligence. Wirel Commun Mob Comput 2022(20):3501003. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3501003

Li Y, Hu C, Huang C, Duan L (2017) The concept of smart tourism in the context of tourism information services. Tour Manag 58:293–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.03.014

Lin J, Niu J, Li H, Atiquzzaman M (2019) A secure and efficient location-based service scheme for smart transportation. Future Gener Comput Syst 92:694–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2017.11.030

Mehraliyev F, Choi Y, Köseoglu MA (2019) Progress on smart tourism research. J Hosp Tour Technol 10(4):522–538. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-08-2018-0076

Melián-González S, Bulchand-Gidumal J, López-Valcárcel BG (2013) Online customer reviews of hotels: as participation increases, better evaluation is obtained. Cornell Hosp Q 54(3):274–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965513481498

Naik MB, Kumar P, Majhi S (2019) Smart public transportation network expansion and its interaction with the grid. Int J Electr Power Energy Syst 105:365–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijepes.2018.08.009

Neuhofer B, Buhalis D, Ladkin A (2015) Smart technologies for personalized experiences: a case study in the hospitality domain. Electron Mark 25(3):243–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0182-1

Okumus B, Ali F, Bilgihan A, Ozturk AB (2016) Factors affecting the acceptance of smartphone diet applications. J Hosp Mark Manag 25(6):726–747. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2016.1082454

Okumus B, Ali F, Bilgihan A, Ozturk AB (2018) Psychological factors influencing customers’ acceptance of smartphone diet apps when ordering food at restaurant. Int J Hosp Manag 72:67–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.01.001

Pearce PL (2020) Tourists’ perception of time: directions for design. Ann Tour Res 83:102932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102932

Sarcona A, Kovacs L, Wright J, Williams C (2017) Differences in eating behavior, physical activity, and health-related lifestyle choices between users and nonusers of mobile health apps. Am J Health Educ 48(5):298–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2017.1335630

Schmidt-Rauch S, Schwabe G (2014) Designing for mobile value co-creation—the case of travel counselling. Electron Mark 24(1):5–17

Sarmah B, Kamboj S, Rahman Z (2017) Co-creation in hotel service innovation using smart phone apps: an empirical study. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 29(10):2647–2667. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2015-0681

Siuhi S, Mwakalonge J (2016) Opportunities and challenges of smart mobile applications in transportation. J Traffic Transp Eng 3(6):582–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2016.11.001

Stankova U, Filimonaub V, Slivarc I (2019) Calm ICT design in hotels: a critical review of applications and implications. Int J Hosp Manag 82:298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.012

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2016) Institutions and axioms: an extension and update of service-dominant logic. J Acad Mark Sci 44(1):5–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-015-0456-3

Vargo SL, Lusch RF (2017) Service-dominant logic 2025. Int J Res Mark 34(1):46–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.11.001

Wang S, Wang J, Li J, Yang F (2020) Do motivations contribute to local residents’ engagement in pro-environmental behaviors? Resident-destination relationship and pro-environmental climate perspective. J Sustain Tour 28:834–852. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1707215

Wang Y, Li H, Li C, Zhang D (2016) Factors affecting hotels’ adoption of mobile reservation systems: a technology-organization environment framework. Tour Manag 53:163–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.09.021

Wang X, Li X, Zhen F, Zhang J (2016) How smart is your tourist attraction?: measuring tourist preferences of smart tourism attractions via a FCEM-AHP and IPA approach. Tour Manag 54:309–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.12.003

Xiang Z, Du Q, Ma Y, Fan W (2017) A comparative analysis of major online review platforms: implications for social media analytics in hospitality and tourism. Tour Manag 58:51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.001

Xiang Z, Stienmetz J, Fesenmaier DR (2021) Smart tourism design: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on designing tourism places. Ann Tour Res 86:103154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103154

Xiang Z, Wang D, O’Leary J, Fesenmaier D (2015) Adapting to the Internet: trends in travelers’ use of the Web for trip planning. J Travel Res 54(4):511–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514522883

Xiao G, Cheng Q, Zhang C(2019) Detecting travel modes using rule-based classification system and Gaussian process classifier IEEE Access 7:116741–116752. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2936443

Ye BH, Ye H, Law R (2020) Systematic review of smart tourism research. Sustain 12(8):3401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083401

Zine P, Kulkarni M, Chawla R, Ray AA (2014) Framework for value co-creation through customization and personalization in the context of machine tool PSS. Procedia CIRP 16:32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2014.01.005

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council under Grant NSTC 109-2410-H-153-031-SSS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C-MC is the single author of this research. He has made substantial contributions to all the works in the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chuang, CM. The conceptualization of smart tourism service platforms on tourist value co-creation behaviours: an integrative perspective of smart tourism services. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 367 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01867-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01867-9