Abstract

Despite many extensive and fruitful studies, assessing and analysing active citizenship behaviours in various cultural contexts remains a topic of research interest. A significant proportion of citizenship studies rely on evidence from adolescents, with their expected participation as the dependent variable rather than the actual civic engagement of adults. Prior research has also neglected to examine the internal civic self-efficacy of adult citizens, particularly concerning gender differences. Based on new data obtained from 731 Turkish citizens over eighteen, this study examines the effects of political media use, civic knowledge, civic self-efficacy, and gender, along with other demographic variables, on civic engagement and participation. We investigate research evidence that women’s tendency to interest in unconventional activities at a higher rate than men would make a difference and enhance their civic self-efficacy. Findings indicate that, at the empirical level, active citizenship is a multidimensional and interrelated concept with dimensions of civic knowledge, civic self-efficacy, engagement, and participation. Civic self-efficacy was found to be a psychological construct that predicts adult citizens’ active citizenship behaviours. Contrary to our hypothesis, gender differences in civic self-efficacy in community engagement closely related to daily life remain present, although women are expected to prefer greater participation than men. Only education indicated some equalising effect. Based on our findings, we suggest that research on citizenship should consider not only whether society values what women do, but also whether it promotes what they value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Citizenship is a multi-layered concept including legal, political, sociological, cultural, psychological, and educational aspects, and many forms of citizenship have arisen in the literature (Isin and Turner, 2002). Although citizen engagement has been valued since ancient times, particularly in the republican paradigm, and several successful and comprehensive studies have been conducted in the past two decades, research investigating active citizenship behaviours in various cultural contexts is still needed.

The functioning of democracy in a country can be best known by examining its civic behaviours. Advanced democracies require active citizenship through deliberative engagement and participation. Globally, this normative requirement has been validated in practice. Cross-national research indicates that the most established democracies show higher active civic participation (Steenekamp and Loubser, 2016). However, the examination of citizenship behaviours in democracies that are outside of the spectrum of advanced democracies has the potential to enhance our understanding of global civic behaviours.

Active citizenship is a value-laden concept, and its normative ground is based on the idea of a democratic state and society, universal human rights, and civil society. However, the political conception of citizenship would substantially affect the actualisation of citizenship behaviours. Classical liberals have long been criticised by communitarian and republican philosophers for neglecting the importance of civic virtues and education, relying solely on liberal institutions and principles for the sustainability of democracy (Sandel, 1996). To respond to this criticism, some liberals developed “a different, more modest and more instrumental, account of civic virtue” (Kymlicka, 2002, p. 299), arguing that “it is both necessary and possible to carry out civic education in the liberal state” (Galston, 1991, p. 242). Whereas Macedo (1990) identified the political, economic, executive, judicial, and legislative liberal virtues necessary for a healthy democratic society, Galston (1991) provides a more comprehensive list of liberal virtues, which includes general virtues, virtues of liberal society, economy, and politics.

Active citizenship is, therefore, essential to all types of democracy. Though public cynicism and discontent with government and politics have hampered civic engagement in advanced democracies, a new pattern of citizen engagement focuses on issues that directly affect their lives and immediate surroundings. Bennett (1998) refers to this pattern as lifestyle politics. In this pattern,

“people continue to be involved politically with lifestyle issues including environmental politics, health and child care, crime and public order, surveillance and privacy, job security and benefits, the organisation of work, retirement conditions, morality in public and private life, the control and content of education, civil rights in the workplace, the social responsibility of corporations, and personalised views of taxation and government spending” (p. 745).

Several studies provide ample documentation of a number of active citizenship factors (Hoskins and Mascherini, 2008; Zaff et al. 2010). Civic engagement through social media, direct contact with politicians and local government officials, and political talk in family and peer groups significantly affect individuals’ political consistency, efficacy, motivation, knowledge, and civic participation. Some of these variables show a two-way interaction, some others mediating or moderating effects (Manganelli et al. 2015; Klofstad, 2009; Russo and Amnå, 2016). Ethnic differences, political polarisation, and extremity are also likely to affect the level and extent of political participation (Guterbock and London, 1983; Tian, 2011).

A significant proportion of citizenship studies rely on evidence from adolescents, with their expected participation as the dependent variable rather than the actual civic engagement of adults (Cohen and Chaffee, 2012; Myoung and Liou, 2022; Velez and Knowles, 2020). However, the adolescent years are unstable, with the most significant potential for a change in political interest occurring between 13 and 15 years of age. Political interest increases substantially and remains relatively stable after age twenty (Russo and Stattin, 2017). Other studies investigating adults’ citizenship behaviours do not include internal civic self-efficacy measures (Marien et al. 2010; Ballard et al. 2016). Civic self-efficacy has the potential to reveal the strengths and weaknesses of citizenship character. Prior research has neglected to examine the internal civic self-efficacy of adult citizens, particularly concerning gender differences. To address this gap, we investigate the relationship between active citizenship factors, including internal civic self-efficacy items for unconventional participation, a domain in which women are apt to exhibit greater self-efficacy than in other domains.

This research is unique because it investigates the direct and mediating effects of important dimensions of active citizenship behaviours in a non-Western, democratically unstable country. Research examining active citizenship behaviours of Turkish citizens is generally event-specific (Bee and Chrona, 2017) or shows inconsistent results (Kalaycioğlu 1994; 2007); Kentmen-Çin, 2015). Second, examining adult citizens’ internal civic self-efficacy has been neglected in previous research. We investigated this variable’s direct and mediating effect on active citizenship behaviours. Thirdly, scholars have argued and provided empirical evidence that men’s and women’s participation types differ substantially (Hooghe and Stolle, 2004). Men are more likely to be interested in conventional activities, whereas women are more likely to engage in unconventional activities, especially those closely related to daily life (Verba et al. 1997). Does this have an effect on women’s levels of self-efficacy? One of the central questions of this paper, therefore, is to examine whether women’s tendency to engage in unconventional activities at a higher rate than men would make a difference in their level of civic self-efficacy. With new evidence obtained from Turkish adults, we aimed to increase our understanding of the global psychological and personal factors associated with active citizenship factors.

Literature review

Civic knowledge and participation

Active citizenship is not simply participating per se but informed participation. Since our decisions and actions about citizenship behaviours are related to our conceptual schema, knowledgeable decisions and actions are likely to promote both the quality and the level of civic engagement. There is a conceptual and causal relationship between civic knowledge and democratic citizenship. Civic knowledge (1) helps citizens to understand their individual and collective interests, (2) increases the consistency of views, (3) supports political understanding, (4) can cause a perspective change in specific public issues, (5) decreases generalised mistrust or alienation, (6) promotes support for democratic values, and (7) political participation (Galston, 2001, pp. 223-4). Effective citizens are knowledgeable and competent individuals who can analyse and evaluate information and ideas and engage in effective problem-solving and decision-making (NCSS, 2001).

This positive relationship between civic knowledge and actual and future participation has been documented in many studies (Solhaug, 2006). Cohen and Chaffee (2012) found that civic content knowledge, current events knowledge, and civic self-efficacy are all individually significant predictors of future voting. Knowledgeable adolescents are more supportive of equal rights regardless of gender and ethnicity. They are more likely to expect to participate in public elections when they reach the age of eligibility (Lauglo, 2013).

Active citizenship programmes, also known as effective citizenship in many countries, have been implemented in the E.U. and other nations since the late 1990s. There is an abundance of research examining the effectiveness of these programmes. Given the results of these studies, formal education as a source of civic knowledge has generally been identified as effective and crucial for preparing students for civic engagement (Campbell, 2008; Prokschová, 2020). Experience and opportunities for public discussion and debate of critical issues; extracurricular and student government activities; and authentic services that enhance civic participation in and identity with one’s community can provide factual knowledge of history and government and encourage students to participate in active citizenship (Youniss, 2011).

Voting is only one form of active citizenship, and there are many civic engagements that support healthy and sustainable democratic governance. Democratic decision-making procedures require both election decisions and conversation before the decision. Since the post-war period, deliberative or discursive democracy has shifted the conception of democracy from a vote-centric to a talk-centric approach (Kymlicka, 2002). In this approach, citizens are required to share and exchange their views by participating in public debates through civil society, social media, and public and private discussions. Citizens have certain individual rights and responsibilities but are also cooperating members of society. As such, citizens are also expected to be both rational and reasonable, tolerant, respect others as persons, and use public reason in political debates. (Rawls, 1996; Brighouse, 2006). For this reason, a deliberative approach to civic and democratic education has been praised for its potential to equip students with knowledge, skills, and dispositions to engage in democratic deliberation in seeking reasonable and mutually beneficial political solutions (Gibson, 2020).

Political media use as a source of political sophistication

Scholars and education experts have often expressed some concern and anxiety about the negative impact of social media on adolescents’ socialisation and academic success. Putnam (2000) named this impact the “time displacement hypothesis” in citizenship studies, which holds that excessive television viewing results in declining civic involvement and participation. The evidence of a strong causal relationship between political information seeking, online political activities, interpersonal political conversation, and conventional engagement forms (Tian, 2011; Nah and Yamamoto, 2018) diminishes concerns about social media’s deleterious impact on youth.

With this positive observation, social media has long been acknowledged as an essential source of civic and political information (McLeod, 2000), and to play a triggering role for politically oriented communicative talk. Regularly conversing about current events within the context of families and groups of friends is a vital component in forming young people’s civic and political identities. Interpersonal communication in the family and peer groups develops young people’s civic orientation and, in turn, affects both their democratic values and practices (Ekström and Östman, 2013). Therefore, both old and new social media can, directly and indirectly, affect active citizenship by stimulating political discourse and mobilising information.

It is important to note that political interest and the level of news follow-up in the media do not depend only on the individual motivation or interest of the citizens. Similar to how political indifference may result if the government disregards citizens’ opinions and interests, news follow-up in the media may decrease if the media demonstrates indifference to the citizens’ experiences, ideas, and real-world circumstances. These situations may overlap in certain nations or circumstances (Wasserman and Garman, 2014). For this reason, significant efforts within formal education have been made to equip adolescents with social media literacy for effective and meaningful civic engagement to mitigate these adverse effects (Martens and Hobbs, 2015). According to Kim and Yang (2015), adolescents’ civic participation is more strongly correlated with Internet information literacy than with Internet skill literacy. People who can understand and critically analyse social media materials are more likely to become engaged citizens than those who do not have these skills.

Civic self-efficacy

The cognitive theory of self-efficacy holds that there is an “independent contribution of the efficacy beliefs to thought processes, motivation, affect, and action” (Bandura 1997, p. 67). Since belief and motivation are necessary for any intentional human action, one’s belief about his or her efficacy is expected to have a causal or functional effect on his or her action. Bandura claimed that self-efficacy influences various human behaviours, including activity selection, perseverance, and performance. Efficacy beliefs are domain-specific, and global efficacy scales fail to measure a particular trait or behaviour (Bandura, 1997). Nevertheless, collective self-efficacy also plays a similar role in human actions, with similar sources, functions, and processes (Bandura, 1997).

A brief conceptual analysis is necessary for the use of civic self-efficacy in citizenship studies. First, civic self-efficacy is different from political or civic efficacy because the object of the former is an internal state; the latter is about people’s beliefs about their impact on political issues, government policies, and practices. Having the capacity to contribute to a cause in civic affairs does not mean that the person has an actual effect because political or civic efficacy largely depends on political governance, on those who exercise power, authority, and control, and whether the communication channels are open between citizens and their representatives and public administrators. For this reason, recent research highlights the difference between internal and external civic self-efficacy (Eidhof and de Ruyter, 2022). Secondly, some studies have measured citizenship behaviours using political efficacy or political self-efficacy scales (Caprara et al. 2009). However, measures with political self-efficacy are limited to a specific domain of citizenship behaviours and do not include community engagements and participation.

It has been reported that civic self-efficacy can predict citizenship participation and future political engagement (Myoung and Liou, 2022); and play a mediating role between knowledge and participation (Manganelli et al. 2015; Reichert, 2016) between political discussion, school participation, and expected participation in legal protest (Zhu, et al. 2018). Individuals with more deliberative thinking likely have more civic efficacy skills and participation (Chung et al. 2021). Research examining civic self-efficacy in school settings is promising. Civic education programmes, open classroom discussions, and student participation in school activities and opportunities can strengthen students’ civic self-efficacy and participation (Manganelli et al. 2015; Tzankova et al. 2020).

Self-efficacy is not just a cognitive ability; it is also highly context-dependent. Likewise, civic self-efficacy demonstrates the same characteristics. Institutional settings and governments’ conceptions and attitudes regarding citizenship can significantly affect civic self-efficacy. For example, statism limits individual associational activity, notably in associations representing new social movement groups (Schofer and Fourcade-Gourinchas, 2001). Government suppression or deliberate ignorance may decrease external civic self-efficacy. Citizens who believe they have limited influence over civic and political events may have a low actualising orientation. Emotional response to public events or policies can result in deliberative or partisan citizenship, influencing citizens’ information processing and behaviours (MacKuen et al. 2010). Citizens with high internal civic self-efficacy and low anticipated influence on democratic governance may exhibit apathy or violent protest behaviour.

Gender and citizenship

Gender and citizenship intersect because both have aspects that are historically, socio-politically, and culturally created; both presuppose certain equal rights and are conceived to some extent differently across societies and cultures. However, the scholarly enquiry on the relationship between feminism and citizenship began to gain attention in the 1990s. Before that, “feminism was not a topic considered by citizenship theorists, nor was citizenship a topic considered by feminist theorists” (Voet, 1998, p. 5). When discussing gender and citizenship, it is necessary to address issues that profoundly affect women’s relationships with other groups and their position in society. Civil, political, and social rights development has undoubtedly contributed to women’s empowerment in public and private domains. However, as Walby (1994, 291) argues, “[a]ccess to citizenship is a highly gendered and ethnically structured process.” Early research on gender differences in citizenship participation focused on factors such as traditional masculine attitudes towards women, inadequate and unequal participation of women in public life, their economic dependence and weakness, and lack of education, as well as inequalities in exercising civil rights and liberties (Mason and Lu, 1988; Komter, 1989; O’Connor, 1993; Burns et al. 2001).

Some feminists argue that citizenship rights are essential to women’s participation and that exercising these rights should be viewed as a means, rather than an end, to achieving equal citizenship (Lister, 2002). In a study employing data from 18 Western industrialised nations, Bolzendahl and Coffé (2009) provided empirical evidence supporting this view. The authors discovered that whereas men and women held similar opinions regarding the significance of political obligations, women placed a substantially higher value on political rights than men. This structure of the transformation process for women has strongly been addressed in feminist political citizenship (Walby, 1990, 1994).

Globally, cultural and religious traditions and beliefs are among the significant determinants of women’s civic engagement to varying extents (Ida and Saud, 2020). Joseph (1996) observed that women’s organisations in Middle Eastern countries are generally state-run, elite-led, and family-dominated or extensions of the ruling political parties. In such a cultural context, women participating in such organisations cannot represent themselves accurately. Behl (2014) demonstrates how Sikh women are hindered from fully exercising their democratic citizenship, as they are restricted to the home and marriage in a pattern of naturalising gendered citizenship. Women’s low labour force participation rate is likely to also affect their civic participation. For example, as of 2020, the employment rate of women aged 15 and older in Turkey was less than half that of men, 26.3% and 59.8%, respectively (TUİK, 2021). In many cases, women’s lack of access to resources and participation is the cause of gender differences. According to Verba et al. (1997), “the absence of activity from members of a resource-deprived group may indicate that they cannot participate, rather than that they do not want to” (p. 1053).

Research shows that women are less likely to participate in political activities, trade union movements, and cultural associations. For example, analysing active citizenship behaviours of around 49000 Italians and 19.000 families, Iezzi and Deriu (2013) found that men and women significantly differ in attending political debates (28,79% of men and 19.60% of women), meetings of cultural associations (12.36% of men and 9.18% of women), and activities of voluntary associations (11.16% of men and 9.97% of women), union associations (2.02% of men and 0.75% of women). Similar results were found by Fakih and Sleiman (2022) in 10 Middle Eastern and North African countries (Algeria, Palestine, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, and Yemen). Women’s situated relationships may result in a line separating institutional citizenship from lived citizenship. Civic activities and institutional politics, like gender roles, may have a gendered meaning. Salmenniemi (2005) has convincingly demonstrated how these two dimensions of citizenship create gendered divisions in post-Soviet Russia’s socio-political organisations with distinct civic duties. In this study, civic activities characterised by feminity include self-sacrifice, responsibility, solidarity, society, and the common good. In contrast, institutional politics characterised by masculinity include self-interest, unreliability, aggressiveness, state and administration, and pursuing careers and power.

Men’s and women’s participation attitudes are not stable but rather sensitive to societal issues and movements. Banaszak et al. (2021) demonstrated that girls’ gender attitudes are more egalitarian than those of males and that the difference between males and girls varies according to the level of gender equality in a country. The actions of protesting women in national news positively affect the more equal gender attitudes of younger people. Men and women may react differently to social issues. For example, in the case of perceived widespread corruption, women are more likely to vote, and men are more likely to engage in elite-challenging forms of involvement (Malmberg and Christensen, 2021).

Measuring women’s participation using universal engagement forms may underestimate the diversity of civic actions that women subjectively value. Research indicates that men and women may differ in their interests and benefit types in civic participation (Schlozman et al. 1995). In a comprehensive study of women’s participation in local-level participation mechanisms in Turkey, Çaha and Çaha (2012) found significant differences in organisation type. Women’s organisations typically engage in activities related to social sensitivity, especially education and health issues, while maintaining a distance from politics and political parties in general. Scholars argue that gender differences cease to be statistically significant when specific interests are controlled for (Ferrin et al. 2020). Therefore, women’s civic engagement must be thoroughly investigated and analysed, and citizenship research should equally consider whether society values what women do and promotes what they value.

Some contextual and individual factors related to citizenship participation in Turkey

Given the evidence that contextual factors significantly affect the level and pattern of civic participation (Kitanova, 2019), it is helpful to describe some political and cultural aspects of the country where this research was conducted. Turkey has been identified as having a statist, strong republican, responsibility-based rather than rights-based citizenship (Keyman and Icduyu, 2003; Ince, 2012; Çaymaz, 2019). The political and historical roots of such a conception lie in the national building process of the new state in the 1920s as a nationalist state with a French republican view.

Several scholars argue that citizenship in Turkey has been nationally and politically gendered from the early republican period to the present. According to Kandiyoti (1991), “a uniform citizenry aborted the possibility for autonomous women’s movements” (p. 43). While women did gain significant civil and political rights with the republican revolutions, the prevailing patriarchal understanding of citizenship continued to influence both the public and private domains. Sirman (2005) characterised this form of citizenship as “familial citizenship.” This concept portrays the ideal citizen as a sovereign husband and head of households, while the wife or mother assumes a dependent role rather than emphasising individuality. During this period, women were seen as the symbols of the Kemalist revolution (Göle, 2010) or symbolic pawns (Kandiyoti, 1988).

Fougner and Kurtoğlu (2016) argue that while Turkey’s E.U. integration process has played a relatively significant role in gender policy in the country, “most gender policy changes since the early 2000s have involved a strong instrumental logic” that lacks a commitment to gender equality as a norm. This instrumentalisation, according to Arat (2022), “contributed to the construction of a new political regime and a new gender ideology” (p. 937) that represents a backslide in the advancement of women’s rights in Turkey. Gender debates in the political arena have remained “a key pillar of populist discourse” (Kandiyoti, 2016) in the country since the 2000s. On 20 March 2021, for instance, the ruling party (AKP) decided to withdraw from the İstanbul Convention, whose primary purpose is to protect women from all forms of violence, declaring an unjustified assertion persistently made by conservatives that the Convention is normalising homosexuality.

Turkey has among the highest rates of voter turnout in OECD countries. In 12 parliamentary elections held between 1983 and 2023, the participation rates ranged between 79.14% and 93.38%. The party membership is also relatively high. As of 23 May 2022, of approximately sixty million Turkish citizens over 18 years old, 14.906784 are political party members (Yargıtay, 2022). However, the distribution of party membership between the ruling party and opposite parties appears interesting. Whereas the ruling party (AKP) has 11. 040,139 (74.06%) members, the remaining 3.866.645 (25.94%) is distributed among other parties, the main opposition party (CHP) having 1.339.150 members.

However, Turkey’s election participation and political party membership rates are greater than those of many other democratic nations may be mainly attributable to Turkey’s political structure. First, political polarisation in Turkey has been significantly higher than in most countries (Lindqvist and Östling, 2010; Aydın-Düzgit and Balta, 2018), and individual autonomy was ranked among the lowest-level countries (Bavetta and Navara, 2012). Secondly, people are interested in politics primarily because of their needs and expectations. In Turkey, the central government’s power in the economy, education, public services, and personnel selection and replacement is relatively high, and the change of political power through elections means the transformation of the owner of the powers invested in these institutions and organisations.

More contextual information could be beneficial. Turkey has been among the collectivist countries with a predominantly Muslim population. The gender gap index for the country is extremely low, ranking 124th out of 146 nations for global gender gap and 114th for political empowerment (WEF, 2022). In Turkey, 94.1% of households and 85.0% of individuals aged 18–75 have internet access. (TUİK, 2023).

These structural and contextual factors emerge in research findings on civic behaviour. Kalaycioğlu (1994; 2007) hypothesised that political orientation, religiosity, urbanisation, extremity, age, gender, and education are Turkey’s primary sources of political participation. He reported that education and political interest are positively correlated with unconventional political participation, whereas religiosity reduces protest behaviour and potential. According to Rumelili and Çakmaklı (2017), ethnic, religious, and political factors are significantly related to the forms of civic actions, cognitive and emotional dimensions of citizenship, and the attitudes and voices of actors in Turkey. Research indicates that right-based civil society organisations are more successful than obligations-based organisations in developing active citizenship practices in the country (Çakmaklı, 2016), and participation in political parties and activities is more prevalent among feminism-oriented women’s organisations than others (Çaha and Çaha, 2012). Harris (2011) observed that Turkish citizens’ environmental attitudes and behaviours are significantly more concerned with local issues, such as traffic problems, air pollution, garbage, and a lack of green space, and less concerned with transnational issues. In Turkey, hometown organisations (hemşeri dernekleri) established by those who migrated from rural areas to big cities after the 1960s for fellow compatriots’ solidarity play a vital role in unconventional civic participation (Caymaz, 2005).

Research model and hypotheses

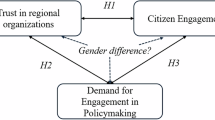

To summarise our research proposal, our primary objective was to identify the factors determining active citizenship. Secondly, given the research evidence regarding gender differences in engagement and participation type, we sought to determine whether this variation would equalise women in the context of the community engagement domain. We developed the following six hypotheses for the research model (Fig. 1) to achieve these objectives.

H1: Political sophistication (civic knowledge and political media use) has a positive effect on civic self-efficacy.

H2: Political sophistication (civic knowledge and political media use) has a positive effect on active citizenship behaviours.

H3: Civic self-efficacy has a positive effect on active citizenship behaviours.

H4: Civic self-efficacy has a mediation effect between political sophistication and active citizenship behaviours.

H5: There is a statistically significant gender difference in civic self-efficacy and active citizenship behaviours.

H6: There are statistically significant correlations between active citizenship and demographic variables such as political orientation, level of education, income, religiosity, and place of residence.

Method

Participants and procedure

The participants consist of 731 Turkish citizens over the age of eighteen. Since our objective was not to represent all Turkish adults but to validate our model and hypotheses, we did not sample the entire population. For this reason, we utilised a random sampling technique for the selection process. Nevertheless, the urban-rural, male-female, large city-small city, and geographical distribution characteristics were considered in selecting participants. Data was taken from nine cities and their surrounding rural areas (Ankara, İstanbul, Çankırı, Kahramanmaraş, Uşak, Trabzon, Diyarbakır, Osmaniye and Bartin) representing six of seven major geographical regions in Turkey. Of the participants, 364 (49.8%) were male, while 365 (49.9%) were female. Two participants (0.3%) did not respond to the gender question. Table 1 provides frequencies and percentages related to gender, age, political orientation, level of education, and monthly income. Except for the first cohort, which accounts for 45% of the present population of Turkey, this distribution approximately represents the current demographics of Turkey’s population. The range of representation for other cohorts is between 75% and 92% (TUİK, 2022).

Data gathering was carried out through in-person surveying by three research members and four graduates hired for this project with sociology master’s degrees and experience in data collection. For this, urban and rural communities, public spaces, private residences, workplaces, educational institutions, and a few associations were in-person visited. The majority of respondents completed the questionnaire themselves. The responses of some participants with literacy and comprehension difficulties, mostly in rural areas, were gathered with the aid of interviewers. Filling the measurement tool required roughly 25 min.

During the informed consent procedure, all participants were informed that their participation and identities would remain anonymous. Anonymity is recognised as a powerful methodological tool for eliminating response biases in Likert scale assessments (Ong and Weiss, 2000). Data were collected between March and September of 2017. Ethics permissions were received from the Ethics Committee at Çankırı Karatekin University.

Measures

Active citizenship is a concept that primarily exists in E.U. policy statements and research agendas (Hoskins et al. 2012). Studies measuring active citizenship often use large-scale international datasets such as the World Values Survey (WVS), the European Social Survey (ESS), The Civic Education Study (CivEd), the European Values Survey (EVS), and the Eurobarometer. However, some of these datasets lack items that measure important aspects of active citizenship. For example, the WVS does not include internal civic self-efficacy, which is among the important aspects of active citizenship; some others limit civic self-efficacy to political self-efficacy. International Social Survey Programme (ISSP, 2014) also does not include civic self-efficacy, while others that do include civic self-efficacy items are designed for adolescents and their expected voting or participation behaviour (CivEd, 2002; ICCS, 2016; Catch-EyoU, 2018) or for some disadvantaged groups such as youth, women, minorities, and migrants (PIDOP). The Active Citizenship Composite Indicator (ACCI) developed by Hoskins et al. (2012) ranks the active citizenship performance of countries rather than individual differences. Because of these limitations, we collected our data using scales validated by the research team in previous studies (Yazıcı et al. 2017; Arslan et al. 2017), and validated items that exist in WVS and ESS. The measuring interval for all items and scales was set at three years. The questionnaire items are presented in the Appendix.

Civic knowledge was measured with four items using a five-point Likert scale from 1 (none) to 5 (very much) in which they were asked to rate how well they know their rights and responsibilities as citizens, the main organs of the state, and the difference between democracy and other forms of government.

Political media use measure consists of three validated items used in WVS. Participants were asked to rate how much time they spent in a day following politics and current affairs by watching television, reading newspapers, and spending on the internet. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (none) to 5 (more than five hours).

The civic self-efficacy scale consists of five items that ask about participants’ ability to participate in community activities, help others, deal with environmental problems, and develop their community. Items were recruited from a previously validated scale by the authors, measuring participants’ self-efficacy in politics, community, and protest and participation. This scale showed good validity and reliability scores (Yazıcı et al. 2017; Arslan et al. 2017), with three factors explaining 57,17% of the total variance and Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.90. For the study, we utilised only items included in the community factor of this scale.

Participation and engagement behaviours were assessed with a total of fourteen validated ESS items. For organisational participation, participants were asked eight items about how often they participate in activities of organisations such as union, cultural, sportive, community, and political organisations (1 = never, 5 = very often). With six items, participants were also asked whether they contacted a politician, government, or local government official, worked in a political party, action group, or another organisation or association, signed a petition, participated in a lawful demonstration, and boycotted certain products within the last 3 years. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (none) to 5 (more than five times).

Demographic variables

Gender was measured as a bivariate 1 female and 2 male, religiosity as a ten-point scale ranging from 0 (not religious at all) to 10 (very religious). Political orientation was asked with two questions. In the first, participants were asked if they were right-, left-, or neither wing. In Turkey, the right-wing and left-wing party system is distinguished by a religious-secular divide rather than a socioeconomic one, unlike in Western societies (Aydogan and Slapin, 2013). However, political studies often employ the terms “left-wing” and “right-wing” to categorise Turkish politics (Çakmaklı, 2016). This classification is also included in the Turkish version of the WVS, and the European Social Survey (ESS). The second question asked to indicate how closely their political beliefs matched those of the major political groups in Turkey, including socialist-communist, social democratic, Kemalist-Ataturk, nationalist, conservative, Islamist, or other. We divided the residential area into five categories: village, small town, town, city, and metropolitan city. Other categories are given in Table 1.

Data analysis

In this study, we employed a quantitative approach to measure the statistical correlation between active citizenship’s determining factors and evaluate the validity of our proposed hypotheses. Our analysis consists of three phases. First, we evaluated the data’s suitability for statistical analysis. The normal distribution assumption was tested by looking at the skewness and kurtosis values of the data. Most statisticians take the values for skewness and kurtosis between −2 and +2 as acceptable for the normal univariate distribution; some others set this criterion to +3 and −3 (George and Mallery, 2016; Sönmez-Çakır, 2020). Given these criteria, the data set showed normal distribution and was suitable for parametric tests.

Secondly, the validity of the research model and hypotheses were tested using partial least square-structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), a licensed feature of the SmartPLS 4 software. Because the study aimed to determine whether the given model was validated, SEM was preferred over simple linear regression.

Thirdly, the effect of gender and other demographic variables on active citizenship factors was analysed using a t test and ANOVA in the SPSS 22 software. The independent samples t test applies when the samples are independent and the average values of the two groups are compared. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) is a statistical method applicable when the samples being compared are independent of each other, and the objective is to compare the mean values of more than two groups. A t test was used to analyse the data for H5, while an ANOVA test was utilised for H6.

Findings

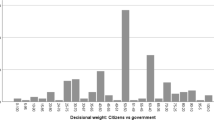

Using confirmatory factor analysis results, we first determined whether the scale’s data were suitable for the model. Table 2 displays the obtained factor loading, t statistics, AVE, CR, and R Square values Fig. 2.

The political media use variable had an outer loading value of 0.65–0.75. the civic knowledge dimension had a value of 0.58–0.83, the civic self-efficacy dimension had a value of 0.54–0.92, the organisational participation dimension had a value of 0.63–0.82, and the demonstration and protest dimension had a value of 0.62–0.75. The t statistic values are greater than 1.96 at the 0.05 significance level, indicating a significant association between the items and their factors. The p values for each of these values were found to be less than 0.05. The confidence interval values, which are not to be expected to be zero between 2.5% and 97.5%, indicate an item’s significance. average variance extracted (AVE) values are expected to be above 0.50, and Cronbach Alpha values and Composite Reliability values, representing reliability values, are expected to be above 0.70 (Hair et al. 2017; Wong, 2019). All obtained AVE values were observed to have a value of 0.50 or greater. Based on the AVE, CR, and Cronbach Alpha values, these results suggest that the scale has adequate reliability. The model’s standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) value was calculated to be 0.06, <0.08, as predicted (Hooper et al. 2008).

The outer model is given in Fig. 2. In this model, political media use and civic knowledge variables were designed as exogenous variables, whereas the remaining variables were designed as endogenous. Figure 2 also shows the t values of the outer loading values of each variable with their items (written in arrows), the path coefficients and t values between the variables (written in arrows), and the Cronbach Alpha values of each variable (written in the round).

In order to verify the model, the data’s validity values must also be examined. For this purpose, the values of the Fornell-Larcker Criterion and Heterotrait Monotrait (HTMT) were interpreted. The values obtained are given in Table 3.

In Table 3, Fornell-Larcker values are calculated by taking the square root of the AVE values, shown in bold and underlined. Discriminant validity is satisfied when these are the highest values in the row and column (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). The remaining numbers in the columns represent correlation values.

If HTMT values exceed 0.85, Discriminant Validity is not achieved (Kline, 2011). MSV is the square of the highest correlation coefficient between latent variables. ASV is the mean of the squared correlation coefficients between latent variables. The MSV and ASV are expected to be less than the AVE value for discriminant validity. According to our data, this criterion has been met.

Table 4 contains the results of hypotheses H1 through H3. In the analysis, the bootstrapping size was determined to be 10,000. Table 4 also provides the path coefficient values derived from the original data (O), the path coefficient values obtained via bootstrapping (M), and the standard deviation values.

The path coefficients are significant if t statistics values are greater than 1.96. Asterisks next to t values indicate that p values are less than 0.05. Only for the H1b hypothesis, the t values are less than 1.96, meaning that the p value is <0.05. This path used in the model was not significant. Other hypotheses were accepted at the 0.05 significance level.

The specific indirect effects values obtained for hypothesis H4 are provided in Table 5. Two of these specific indirect effect values are significant (t statistic value > 1.96), while the others are not. Consequently, the CSE variable mediates the relationship between CK and OP and CK and DP Hypotheses H4a and H4b, therefore, are accepted. Hypotheses H4c and H4d were rejected because the indirect effect pathways were insignificant.

Since the specific indirect effects are insufficient for the mediation effect, the size of this effect must be calculated. The variance accounted for (VAF) value was calculated and interpreted for this purpose. According to Hair et al. (2021), a VAF value >80% indicates full mediation, between 20% and 80% partial mediation, and less than 20% no mediation effect. The VAF Value is found by dividing the indirect effect by the total effect (Sarstedt et al. 2014). The results are presented in Table 6.

The coefficient between the gender variable and other variables varies significantly and negatively. The calculated path coefficients are CK: −0.43 (5.59), DP: −0.32 (4.62), OP −0.21 (2.68), and PMU: −0.29 (3.36). These results are also evident from the SPSS t test analysis.

The t test results indicated a significant difference between the average scores of male and female participants. More specifically, the t test values in the political media use (t: 3.131; Sig: 0.000), civic knowledge (t: 4.495; Sig: 0.000), participation (t: 3.922; Sig: 0.000), the demonstration and protest dimension (t: 6.659; Sig: 0.000) and civic self-efficacy (t: 2.552; Sig: 0.011) were found significant at the 0.05 level. As seen in Table 7, male participants showed higher active citizenship scores than females.

The ANOVA test results in Table 8 of the Appendix revealed a significant difference between the place of residence and the participation dimension (F: 2.622; Sig.: 0.034). The mean scores of those living in villages and those living in cities and metropolises were statistically different (LSD Sig.: 0.004 for Village-City; LSD Sig.: 0.014 for Village-Metropolitan). Those living in villages have a significantly lower mean score than those living in cities and metropolises. Similarly, for the demonstration and protest dimension, a significant difference was found between the place of residence and the average scores of the demonstration and protest dimension (F: 3.457; Sig.: 0.008). Those living in the villages have significantly lower mean scores of demonstrations and protests than those living in large cities.

Discussion

Despite numerous successful and exhaustive studies, measuring determinants of active citizenship behaviours is still in its infancy. The findings of this study revealed that, at the empirical level, active citizenship is a multidimensional and interrelated concept with dimensions of political sophistication, civic self-efficacy, civic engagement, and participation. Accordingly, our research model is supported.

This study provides evidence that individuals with higher levels of political knowledge and social media use are more likely to report participating in civic activities such as contacting officials and participating in political campaigns, volunteering, and community organisations. There are several potential explanations for this relationship. Individuals with higher levels of political sophistication may be more aware of their communities’ issues and problems. They may feel a greater sense of responsibility to take action to address these issues. They may also have greater access to information about getting involved and feel more confident in making a difference. The relationship between political sophistication and active citizenship may be reciprocal. Engaging in active citizenship behaviours may increase an individual’s political knowledge and understanding, encouraging them to become more politically sophisticated. Promoting political education and engagement among individuals, particularly young people, may be an effective way to encourage more active citizenship and increase civic participation.

Previous studies that include civic self-efficacy as a direct and mediating effect to predict citizenship behaviours have drawn evidence from adolescent students (Manganelli et al. 2015; Ballard et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2018; Velez and Knowles, 2020). This study highlights that civic self-efficacy is a psychological construct that predicts adult citizens’ active citizenship behaviours. The meditation analysis in our study suggests that civic self-efficacy mediates between civic knowledge, political media use, and active citizenship behaviours. This direct and mediating influence of civic self-efficacy on active citizenship behaviour is significant for civic education policies and strategies.

We considered it essential to examine whether women’s tendency to engage in unconventional activities at a higher rate than men would make a difference and enhance their civic self-efficacy. However, contrary to our hypothesis and previous evidence that women are likely to engage in unconventional activities at a higher rate, it did not indicate a positive effect on their civic self-efficacy level in a community engagement setting. In the Turkish context, women are fewer participants and engaged individuals in all forms of participation with lower-level civic self-efficacy. In our study, women also declared a higher level of apolitical orientation. Of the 249 who declared their political view as ‘None’, 142 were women.

In general, the gender differences in political interests and citizenship participation are likely to be a function of socialisation and women’s lower rates of higher education graduates (Sherkat and Blocker, 1994). Additionally, the absence of resources and cognitive abilities among citizens with lower levels of education undermines their participation (Marien et al. 2010). Our findings are consistent with research that the gap between gender differences is narrowing as education levels rise (Castro and Díaz-García, 2020). For example, while the average organisational participation scores of men (1.88, 1.65) and women (1.31, 1.38) were significantly lower for primary and secondary school graduates, they were significantly higher for university and master’s degree graduates of men (1.82, 1.87) and women (1.71, 2.12).

Limited studies that examined individual factors regarding citizenship behaviours in Turkey reported mixed results. Using data from the 2008 European Values Survey, Kentmen-Çin (2015) found that unconventional political activism is statistically unrelated to gender, income, extreme political orientation, lack of partisanship, and the size of the living town. The author reported a positive correlation between unconventional political activism and education level and democratic satisfaction level. Kalaycioğlu discovered a negative correlation between religiosity and unconventional participation. Our findings contradict Kentmen-Çin’s and Kalaycioğlu’s findings in several variables. Unlike the former, we found statistical differences in gender, income, educational level, and political orientation. Unlike the latter, no statistical differences were observed between active citizenship behaviours and religiosity. One possible explanation for these inconsistent results is that our questionnaire includes conventional and unconventional participation behaviours, including community engagement. Both Kalaycioğlu’s and Kentmen-Çin’s studies represent a limited aspect of unconventional political participation behaviours covering only protest behaviours and potential with five items, some of which (i.e., ‘occupation of buildings or offices’) are not included in active citizenship behaviours in recent literature. Studies in Western countries show that religiosity is positively correlated with religious and non-religious citizenship engagement (Strom, 2015). Kalaycioğlu (1994; 2007) and Chrona and Capelos (2016) reported contrary evidence for Turkish participants. In their studies, whereas religious people are more likely to use formal channels, non-religious people are more likely to resist the barriers of formal participation. Our results align with those of Erdoğan and Uyan-Semerci (2017), who discovered that age, gender, economic position, and urban or rural residence have a more significant influence on active civic participation in Turkey. While no statistically significant difference between the rightist and the leftist participants was found, there was a significant difference between those who declared their political view as “none” and those who declared rightist and leftist.

We measured the direct and mediating effects of internal self-efficacy in this study. Incorporating both internal self-efficacy and external self-efficacy in future research can shed light on governmental policies and practices about active citizenship. Examining the rationales and motivations that prompt individuals to engage in civic engagement may also provide valuable insights into the strengths and weaknesses of civic virtues within a society. Additional investigation might be conducted to explore this subject using in-depth interviews in the Turkish context.

Limitations of the study

Although the purpose of this study is to evaluate active citizenship behaviours in the setting of Turkey, the scope of the research does not involve a direct examination of contextual factors. Contextual factors make civic behaviour challenging to measure and interpret protest behaviours and attitudinal motivations because they are related to specific circumstances, issues, political actors, mobilisation processes, and cultural frames around the protest event (Norris et al. 2005). Chrona’s and Capelos’ analysis (2016) indicated that whereas a simple model can explain conventional participation in Turkey, political decision-making of unconventional participation appears to rest on a complex psychological cognition. Secondly, while this study’s sample size is suitable for testing hypotheses, it does not adequately reflect the nation’s regions. A bigger sample size may be used to test these hypotheses and variables in future studies.

Lastly, the conclusions drawn in this research were derived from data that was gathered in the year 2017. Since then, there have been some changes to the political atmosphere in Turkey. For example, according to Freedom House reports, the country’s global freedom status deteriorated from partially free in 2017 to not free in 2023. In this context, it is essential to acknowledge that our findings include some limitations in precisely describing current civic behaviours prevalent in Turkey.

Conclusion

This study is unique in examining civic self-efficacy with adult participants in community engagement, where women are apt to demonstrate a higher efficacy level than men. Previous research indicated that active citizenship behaviours are not evenly distributed among all members of society. Some individuals and groups may face barriers to participating in these behaviours, such as lack of time, resources, social capital, skills, and social or cultural barriers. The findings of this study are consistent with previous research that individuals who are more engaged in their communities and the greater society tend to have higher levels of political orientation, civic knowledge, democratic values, education, and wealth and are more likely to be male. Promoting active citizenship behaviours is essential to building strong and vibrant communities. Given its direct and mediating effect, enhancing civic self-efficacy through instructional practices, school socialisation, participation in civic action projects, and supportive adult relationships is vital. This study highlights that the difference in participation type at a higher level without actual participation does not empower women’s civic self-efficacy. Based on our findings, we suggest that research on citizenship should consider not only whether society values what women do, but also whether it promotes what they value. Communities and governments must work towards creating more inclusive and accessible opportunities for active citizenship.

Data availability

The data and materials reported here are available in supplementary files.

References

Arat Y (2022) Democratic backsliding and the instrumentalisation of women’s rights in Turkey. Politics Gend 18:911–941

Arslan H, Dil K, Çetin E, Yazıcı S (2017) Active citizenship self-efficacy scale: a reliability and validity study. Int J Hum Sci 14:2797–2809

Aydın-Düzgit S, Balta E (2018) When elites polarise over polarisation: framing the polarisation debate in Turkey. New Perspect Turk 60:153–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/npt.2018.15

Aydogan A, Slapin JB (2013) Left–right reversed. Party Politics 21:615–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068813487280

Ballard PJ, Cohen AK, Littenberg-Tobias J (2016) Action civics for promoting civic development: main effects of program participation and differences by project characteristics. Am J Commun Psychol 58:377–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12103

Banaszak LA, Liu S-JS, Tamer NB (2021) Learning gender equality: how women’s protest influences youth gender attitudes. Polit Groups Identities 11:74–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2021.1926296

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co, New York

Bavetta, S, Navara, P (2012) The economics of freedom: theory, measurement, and policy implications, Cambridge University Press

Bee C, Chrona S (2017) Youth activists and occupygezi: patterns of social change in public policy and in civic and political activism in Turkey. Turkish Stud 18:157–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2016.1271722

Behl N (2014) Situated citizenship: understanding Sikh citizenship through women’s exclusion. Polit Groups Identities 2(3):386–401

Bennett WL (1998) The uncivic culture: communication, identity, and the rise of “lifestyle politics”. PS Political Sci Politics 31:41–61

Bolzendahl C, Coffé H (2009) Citizenship beyond politics: the importance of political, civil and social rights and responsibilities among women and men1. Br J Sociol 60:763–791. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01274.x

Brighouse, H (2006) On education. Routledge, London

Burns N, Schlozman, KL, Verba S (2001). The private roots of public action: Gender, equality, and political participation. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Çaha Ö, Çaha, H (2012) Yerelde tango: Kadın örgütleri ve yerel demokrasi (Tango at the local: Women’s organizations and local democracy). Orion Kitapevi, Ankara

Çakmaklı D (2016) Rights and obligations in civil society organisations: learning active citizenship in Turkey. Southeast Eur Black Sea Stud 17:113–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1244236

Campbell DE (2008) Voice in the classroom: how an open classroom climate fosters political engagement among adolescents. Polit Behav 30:437–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-008-9063-z

Caprara GV, Vecchione M, Capanna C, Mebane M (2009) Perceived political self-efficacy: theory, assessment, and applications. Eur J Soc Psychol 39:1002–1020. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.604

Castro PFD, Díaz-García O (2020) Active citizenship and political participation of women in Spain. Rev de Cienc Soc 15:501–530. https://doi.org/10.14198/OBETS2020.15.2.05

Catch-EyoU (2018) Political identification and engagement among European youth: Findings from the longitudinal. study https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5bbde210c&appId=PPGMS

Caymaz B (2005) İstanbul’da Niğdeli Hemşehri Dernekleri. Eur J Turkish stud. https://doi.org/10.4000/ejts.410

Çaymaz B (2019) Türkiye’de vatandaşlığın inşası. Yeniinsan Yayınevi, İstanbul

Chrona S, Capelos T (2016) The political psychology of participation in Turkey: civic engagement, basic values, political sophistication and the young. Southeast Eur Black Sea Stud 17:77–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2016.1235002

Chung M-L, Fung KK, Chiu EM, Liu C-L (2021) Toward a rational civil society: deliberative thinking, civic participation, and self-efficacy among taiwanese young adults. Polit Stud Rev 20:608–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/14789299211024440

CivEd (2002) Civic knowledge and engagement. The international association for the evaluation of educational achievement: Amsterdam, https://www.iea.nl/sites/default/files/2019-04/CIVED_Phase2_Upper_Secondary.pdf

Cohen AK, Chaffee BW (2012) The relationship between adolescents’ civic knowledge, civic attitude, and civic behavior and their self-reported future likelihood of voting. Educ Citizsh Soc Justice 8:43–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197912456339

Eidhof B, de Ruyter D (2022) Citizenship, self-efficacy and education: a conceptual review. Theory Res Educ 20:64–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/14778785221093313

Ekström M, Östman J (2013) Family talk, peer talk and young people’s civic orientation. Eur J Commun 28:294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323113475410

Erdoğan E, Uyan-Semerci P (2017) Understanding young citizens’ political participation in Turkey: does ‘being young’ matter? Southeast Eur Black Sea Stud 17:57–75

Fakih A, Sleiman Y (2022) The gender gap in political participation: evidence from the MENA region. Rev Polit Econ 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09538259.2022.2030586

Ferrin M, Fraile M, Garcia-Albacete GM, Gomez R (2020) The gender gap in political interest revisited. International Political Science Review 41(4):473–489

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Market Res 18:382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

Fougner T, Kurtoğlu A (2016) Gender policy: a case of instrumental Europeanization? In: Güney A, Tekin A (Eds.) Europeanization of Turkish public policies: a scorecard. Routledge. New York

Galston WA (1991) Liberal purposes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Galston WA (2001) Political knowledge, political engagement, and civic education. Annu Rev Polit Sci 4:217–234. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.217

George, D., & Mallery, P. 2016. IBM SPSS statistics 23 step by step: a simple guide and reference. Routledge, London

Gibson M (2020) From deliberation to counter-narration: Toward a critical pedagogy for democratic citizenship. Theory Res Soc Educ 48:431–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2020.1747034

Göle, N. (2010). Modernleşme bağlamında İslami kimlik arayısı (The struggle for Islamic identity in the context of modernization). In: eds. Bozdoğan S, Kasaba R (Eds.) Türkiye’de Modernleşme ve Ulusal Kimlik (Modernization and national identity in Turkey), Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, İstanbul

Guterbock TM, London B (1983) Race, political orientation, and participation: an empirical test of four competing theories. Am Soc Rev 48:439. https://doi.org/10.2307/2117713

Hair JF, Hollingsworth CL, Randolph AB, Chong AYL (2017) An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind Manag Data Syst 117:442–458

Hair JR, Hult JF, MG Tomas, Ringle C M, Sarstedt M (2021) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications, London

Harris LM (2011) Neo(liberal) citizens of Europe: politics, scales, and visibilities of environmental citizenship in contemporary Turkey. Citizsh Stud 15:837–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2011.600095

Hooghe M, Stolle D (2004) Good girls go to the polling booth, bad boys go everywhere. Women Polit 26:1–23

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M (2008) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods 6:53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

Hoskins B, Villalba CMH, Saisana M (2012) The 2011 civic competence composite indicator. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Hoskins BL, Mascherini M (2008) Measuring Active Citizenship through the Development of a Composite Indicator. Social Indicators Research 90:459–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9271-2

ICCS (2016). Becoming Citizens in a Changing World: IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2016 International Report, file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/978-3-319-73963-2.pdf

Ida R, Saud M (2020) The narratives of shia madurese displaced women on their religious identity and gender citizenship: a study of women and Shi’as in Indonesia. J Relig Health 60:1952–1968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01001-y

Iezzi DF, Deriu F (2013) Women active citizenship and wellbeing: the Italian case. Qual Quant 48:845–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-012-9806-0

Ince B (2012) Citizenship and Identity in Turkey: From Atatürk’s Republic to the Present Day. I.B. Tauris

Isin EF, Turner BS (2002) Citizenship studies: an introduction. In: Isin E F, Turner BS (Eds.) Handbook of citizenship. Sage Publication Ltd, London

ISSP (2014) “Citizenship II” - No. 6670, https://www.gesis.org/en/issp/modules/issp-modules-by-topic/citizenship/2014

Joseph S (1996) Gender and citizenship in Middle Eastern States. Middle East Report 4. https://doi.org/10.2307/3012867

Kalaycioğlu E (1994) Unconventional political participation in Turkey and Europe: comparative perspectives. Il Politico 59(3):503–524

Kalaycıoğlu E (2007) Religiosity and protest behaviour: the case of Turkey in comparative perspective. J Southern Europe Balkans 9:275–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613190701689977

Kandiyoti D (1991) End of empire: Islam, nationalism and women in Turkey. In: D Kandiyoti (Ed) Women, Islam and the State. Macmillan London

Kandiyoti D (1988) Bargaining with patriarchy. Gender Soc 2:274–290

Kandiyoti D (2016) Locating the politics of gender: Patriarchy, neo-liberal governance and violence in Turkey. Res Policy Turkey 1:103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/23760818.2016.1201242

Kentmen-Çin Ç (2015) Participation in social protests: comparing Turkey with E.U. patterns. Southeast Eur Black Sea Stud 15:223–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683857.2015.1015314

Keyman EF, Icduyu A (2003) Globalization, Civil Society and Citizenship in Turkey: actors, boundaries and discourses. Citizsh Stud 7:219–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362102032000065982

Kim E, Yang S (2015) Internet literacy and digital natives’ civic engagement: Internet skill literacy or Internet information literacy? J Youth Stud 19:438–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1083961

Kitanova M (2019) Youth political participation in the E.U.: evidence from a cross-national analysis. J Youth Stud 23:819–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1636951

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). Guilford Press, New York

Klofstad CA (2009) Civic talk and civic participation. Am Polit Res 37:856–878. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673x09333960

Komter A (1989) Hidden power in marriage. Gender Soc 3:187–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124389003002003

Kymlicka W (2002) Contemporary political philosophy: an introduction. Second edition, Oxford University Press, New York

Lauglo J (2013) Do more knowledgeable adolescents have more rationally based civic attitudes? Analysis of 38 countries. Educ Psychol 33:262–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.772773

Lindqvist E, Östling R (2010) Political polarisation and the size of government. Am Polit Sci Rev 104:543–565. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055410000262

Lister R (2002) Sexual citizenship. In: Isin E F, Turner BS (Eds.) Handbook of citizenship. Sage Publication Ltd, London

Macedo S (1990) Liberal virtues. Clarendon Press, Oxford

MacKuen M, Wolak J, Keele L, Marcus GE (2010) Civic engagements: resolute partisanship or reflective deliberation. American J Polit Sci 54:440–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00440.x

Malmberg FG, Christensen HS (2021) Voting women, protesting men: a multilevel analysis of corruption, gender, and political participation. Polit Policy 49:126–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12393

Manganelli S, Lucidi F, Alivernini F (2015) Italian adolescents’ civic engagement and open classroom climate: the mediating role of self-efficacy. J Appl Dev Psychol 41:8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.07.001

Marien S, Hooghe M, Quintelier E (2010) Inequalities in non-institutionalised forms of political participation: a multi-level analysis of 25 countries. Polit Stud 58:187–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

Martens H, Hobbs R (2015) How media literacy supports civic engagement in a digital age. Atlantic J Commun 23:120–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2014.961636

Mason KO, Lu Y-H (1988) Attitudes towrds women’s familial roles. Gend Soc 2:39–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124388002001004

McLeod JM (2000) Media and civic socialisation of youth. J Adolesc Health 27:45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00131-2

Myoung E, Liou P-Y (2022) Adolescents’ political socialization at school, citizenship self-efficacy, and expected electoral participation. J Youth Adolesc 51:1305–1316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01581-w

Nah S, Yamamoto M (2018) The integrated media effect: rethinking the effect of media use on civic participation in the networked digital media environment. Am Behav Sci 62:1061–1078. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218764240

NCSS (2001) Creating effective citizens. NCSS position statement. http://www.socialstudies.org/positions/effectivecitizens

Norris P, Walgrave S, Van Aelst P (2005) Who demonstrates? antistate rebels, conventional participants, or everyone? Comp Polit 37:189. https://doi.org/10.2307/20072882

O’Connor JS (1993) Gender, class and citizenship in the comparative analysis of welfare state regimes: theoretical and methodological issues. Br J Sociol 44:501. https://doi.org/10.2307/591814

Ong AD, Weiss DJ (2000) The impact of anonymity on responses to sensitive questions1. J Appl Soc Psychol 30:1691–1708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02462.x

Prokschová D (2020) Schools for democracy: a waste of time? roles, mechanisms and perceptions of civic education in Czech and German contexts. Sociológia - Slovak Sociol Rev 52:300–320. https://doi.org/10.31577/sociologia.2020.52.3.13

Putnam R (2000) Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York

Rawls J (1996) Political Liberalism. Colombia University Press, New York

Reichert F (2016) How internal political efficacy translates political knowledge into political participation: evidence from Germany. Eur J Psychol 12:221–241. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v12i2.1095

Rumelili B, Çakmaklı D (2017) Civic participation and citizenship in turkey: a comparative study of five cities. South European Soc Polit 22:365–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2017.1354420

Russo S, Amnå E (2016) When political talk translates into political action: the role of personality traits. Pers Individ Differ 100:126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.009

Russo S, Stattin H (2017) Stability and change in youths’ political interest. Soc Indic Res 132:643–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1302-9

Salmenniemi S (2005) Civic activity – feminine activity? Sociology 39:735–753. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038505056030

Sandel M (1996) Democracy’s discontent: America in search of a public philosophy. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Smith D, Reams R, Hair JRJF (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J Family Bus Strategy 5:105–115

Schlozman KL, Burns N, Verba S, Donahue J (1995) Gender and citizen participation: is there a different voice? Am J Polit Sci 39:267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111613

Schofer E, Fourcade-Gourinchas M (2001) The structural contexts of civic engagement: voluntary association membership in comparative perspective. Am Soc Rev 66:806. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088874

Sherkat DE, Blocker TJ (1994) The political development of sixties’ activists: identifying the influence of class, gender, and socialization on protest participation. Social Forces 72:821. https://doi.org/10.2307/2579782

Sirman N (2005). The making of familial citizenship in Turkey. In: Keyman F, İçduygu A (eds.) Challenges to Citizenship in a Globalising World: European Questions and Turkish Experiences, Routledge, London

Solhaug T (2006) Knowledge and self-efficacy as predictors of political participation and civic attitudes: with relevance for educational practice. Policy Futures Educ 4:265–278. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2006.4.3.265

Sönmez-Çakır F (2020) Sosyal Bilimler için parametrik veri analizi. Gazi Kitabevi, Ankara

Steenekamp C, Loubser R (2016) Active citizenship: a comparative study of selected young and established democracies. Politikon 43:117–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589346.2016.1155141

Strom I (2015) Civic engagement in Britain: the role of religion and inclusive values. Eur Sociol Rev 31:14–29

Tian Y (2011) Communication behaviors as mediators: examining links between political orientation, political communication, and political participation. Commun Qtly 59:380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2011.583503

TUİK (2021). İstatistiklerle Kadın, https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Istatistiklerle-Kadin-2021-45635

TUİK (2022) The results of address based population registration system. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=49685

TUİK (2023). Household Information Technologies (I.T.) Usage Survey, 2022. https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Hanehalki-Bilisim-Teknolojileri-(BT)-Kullanim-Arastirmasi.-2022

Tzankova I, Prati G, Eckstein K et al. (2020) Adolescents’ patterns of citizenship orientations and correlated contextual variables: results from a two-wave study in five European countries. Youth & Society 53:1311–1334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118x20942256

Velez GM, Knowles RT (2020) Trust, civic self-efficacy, and acceptance of corruption among Colombian adolescents: shifting attitudes between 2009-2016. Compare 52:1205–1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2020.1854084

Verba S, Burns N, Schlozman KL (1997) Knowing and caring about politics: gender and political engagement. J Politics 59:1051–1072. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998592

Voet R (1998) Feminism and Citizenship. Sage Publication, London

Walby S (1990) Theorizing Patriarch. Blackwell, Oxford

Walby S (1994) Is citizenship gendered? Sociology 28:379–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038594028002002

Wasserman H, Garman A (2014) The meanings of citizenship: media use and democracy in South Africa. Soc Dyn 40:392–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2014.929304

WEF (2022). Global Gender Gap Report 2022. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf?_gl=1*1ndymng*_up*MQ..&gclid=CjwKCAjw_aemBhBLEiwAT98FMmiNBs54_W4iwLw0W4yyKYshmm8ZRPc1XB6YAJsaHeGKCCn8RrJzFRoCKScQAvD_BwE

Wong KKK (2019) Mastering partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) with Smartpls in 38 hours, Bloomington: iUniverse

Yargıtay, (2022). Siyasi parti genel bilgileri, https://www.yargitaycb.gov.tr/kategori/109/siyasi-parti-genel-bilgileri

Yazıcı S, Arslan H, Çetin E, Dil K (2017) A study on the development of active citizen questionnaire. Turkish Stud 12:251–271,. https://doi.org/10.7827/TurkishStudies.11645

Youniss J (2011) Civic education: what schools can do to encourage civic identity and action. App Dev Sci 15:98–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2011.560814

Zaff J, Boyd M, Li Y et al. (2010) Active and engaged citizenship: multi-group and longitudinal factorial analysis of an integrated construct of civic engagement. J Youth Adolesc 39:736–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9541-6

Zhu J, Kuang X, Kennedy KJ, Mok MMC (2018) Previous civic experience and Asian adolescents’ expected participation in legal protest: mediating role of self-efficacy and interest. Asia Pac J Educ 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2018.1493980

Parissa J., Ballard Alison K., Cohen Joshua, Littenberg‐Tobias (2016) Action Civics for Promoting Civic Development: Main Effects of Program Participation and Differences by Project Characteristics Abstract American Journal of Community Psychology 58(3-4) 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12103

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit of Çankırı Karatekin University (Grant number: EF90316B12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the design and development of data collection instruments and discussion section. H-A, K-D and E-Ç directed and participated in data collection and funding acquisition. S-Y and H-A contributed to the methodology, the literature review, writing, and reviewing, and F-SÇ contributed to the methodology and statistical analysis. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from Çankırı Karatekin University Ethics Committee (Approval number: 01.09.2014-07).

Informed consent

This research was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to the interviews, all participants were required to sign a permission form stating their willingness to participate and complete the study’s questionnaire in order to provide their informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arslan, H., Yazıcı, S., Çetin, E. et al. Political media use, civic knowledge, civic self-efficacy, and gender: measuring active citizenship in Turkey. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 791 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02281-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record: