Abstract

Recent advances in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) resonators have enabled the development of compact devices capable of precise magnetic and electric field sensing. This review focuses on resonant MEMS sensors that employ electrostatic actuation, offering advantages such as low power consumption, fast mechanical response, and CMOS-compatible fabrication. We classify two primary types of resonant MEMS sensors based on their sensing mechanisms, where magnetic field sensors utilize electromagnetic induction and electric field sensors rely on electrostatic induction. For each type, we analyze representative devices in terms of actuation schemes, resonator design strategies, sensitivity enhancement techniques, and directional detection capability. We also address key design considerations and fabrication constraints. The review summarizes current approaches and characteristics of MEMS resonator-based magnetic and electric field sensors with a focus on their structural principles and application contexts. Through this analysis, the review aims to provide insights that support the development of next-generation field sensors for applications in navigation, biomedical diagnostics, vehicle detection, and non-destructive evaluation of electrical systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A microelectromechanical system (MEMS) is a micrometer-scale transducer that integrates microstructures and electrical circuits1,2. MEMS devices offer advantages due to their small size, various energy conversion principles, and integrated circuit (IC) compatibility. The development of durable micromachining tools and packaging technologies has enhanced the recognition of MEMS in the modern electronics industry, enabling their applications across various industrial fields3,4,5,6. Because of the diversity of applicable energy conversion schemes, MEMS sensors are widely employed to detect a range of chemical, mechanical, and electrical properties. Compared to macroscale sensors, MEMS sensors provide reduced size and weight, compatibility with other systems, and low manufacturing cost through batch fabrication. In terms of sensing performance, MEMS sensors offer high reliability, fast response, and high sensing resolution. These characteristics of MEMS devices make them excellent candidates for detecting magnetic and electric fields2,3,4.

MEMS magnetic field sensors based on electromagnetic induction measure the induced voltage generated by changes in the effective area of the induction coil within a magnetic field. MEMS electric field sensors utilizing electrostatic induction measure electric fields by converting current, induced by charge changes in sensing electrodes under electric fields, into voltage. Both magnetic and electric field sensing mechanisms require the movable components of MEMS sensors to generate repeated, large mechanical displacements for effective operation. Therefore, the integration of resonators is crucial for the functionality of these sensors. Typical resonant driving methods for MEMS include electrothermal, electromagnetic, piezoelectric, and electrostatic actuation, each with its own advantages and disadvantages5,6. The selection among these methods depends on the design objectives and operating conditions.

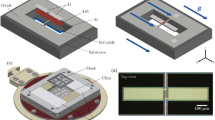

Electrostatic forces arise from attractive or repulsive interactions between charged conductors and are widely exploited as an effective actuation mechanism in MEMS due to their low power consumption, high-speed response, and compatibility with standard microfabrication processes. Electrostatic MEMS actuators are typically classified into two main categories: gap-closing actuators and comb-drive actuators, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Gap-closing actuators generate motion by applying a voltage between two parallel electrodes, generating electrostatic force that draws the electrodes toward each other, as shown in Fig. 1a7,8,9. The resulting actuation is inherently nonlinear, as the electrostatic force increases sharply with decreasing gap distance. This nonlinearity leads to a pull-in instability, which limits the maximum stable displacement and compromises device reliability7. As a result, the operational range of gap-closing actuators is constrained, making them less suitable for applications that require large or precisely controllable displacements.

To address these limitations, comb-drive actuators have been developed10,11,12,13. Comb-drive actuators, as presented schematically in Fig. 1b, consist of interdigitated finger-like electrodes arranged laterally. Unlike gap-closing structures, the electrostatic force in comb drives is largely independent of displacement and is instead governed by the geometry of the comb structure, including finger width, overlap length, and gap spacing. This results in a nearly constant and linear force over the range of motion, which in turn facilitates precise displacement control with high resolution and enhanced operational stability. Moreover, the comb-drive architecture can be efficiently fabricated using standard planar micromachining techniques, offering advantages in scalability and IC-compatibility14. Due to these benefits, comb-drive actuators have been widely adopted in various MEMS applications, including resonators, inertial sensors, micro-mirrors, and optical scanning systems.

Electrostatic MEMS actuators offer key advantages such as low power consumption, fast response time, and compatibility with standard microfabrication processes. Although they often require relatively high driving voltages to achieve large displacement for resonance operation, the absence of current flow across the dielectric gap allows for extremely low power consumption compared to other actuation methods. The simplicity of their structural design also facilitates easy integration with ICs, making them highly attractive for compact and scalable MEMS systems. Given that gap-closing actuators offer compactness but are constrained by pull-in effects, and comb-drive actuators provide broader design flexibility with improved stability and resolution, careful selection between the two is essential depending on specific design goals and operational environments. Building upon these foundational characteristics, this review focuses on MEMS sensors that detect magnetic and electric fields by applying electrostatic resonance actuation. Additionally, we also discuss their potential applications and highlight the challenges that remain to be addressed.

Electrostatic actuation for MEMS resonators

Electrostatic actuation is one of the most prevalent driving schemes for MEMS resonators, offering simplicity, scalability, and compatibility with standard microfabrication processes15. Because the generated electrostatic force depends nonlinearly on both the applied voltage and electrode displacement, such systems inherently exhibit complex dynamic behaviors that govern the resonance stability and sensing performance16,17. Stable and reliable operation requires precise driving and control schemes capable of maintaining consistent resonance amplitude and phase under variations in temperature, humidity, and other environmental disturbances18. In this section, we discuss the nonlinear dynamics governing electrostatically actuated MEMS resonators and introduce the open-loop and closed-loop control schemes including self-oscillation and phase-locked loop (PLL) that ensure long-term frequency and amplitude stability as well as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) enhancement in resonator-based sensors.

Nonlinear dynamics in electrostatic resonators

Electrostatic actuation can induce nonlinear dynamic effects in MEMS resonators, and the extent of these effects depends on actuator geometry and operating conditions19,20. Because the capacitance varies inversely with the electrode gap in parallel-plate configurations, the electrostatic force increases nonlinearly with displacement21. This quadratic voltage dependence leads to electrostatic softening and pull-in instability, while geometric nonlinearities in the mechanical stiffness can counteract this effect, producing either overall softening or hardening behavior depending on the design. In contrast, comb-drive actuators are designed so that the overlap area between interdigitated fingers changes nearly linearly with lateral motion, yielding an approximately constant force for small displacements. However, under torsional oscillation or unintended rotational coupling, even comb-drive resonators can exhibit amplitude-dependent resonance shifts and effective stiffness variations, leading to either softening or hardening behavior depending on structural symmetry and operating conditions22,23. When the applied voltage becomes sufficiently large, the effective stiffness decreases due to electrostatic softening, causing resonance-frequency shifts and potential pull-in collapse when the attractive force exceeds the restoring force24.

In multi-degree-of-freedom MEMS devices such as gyroscopes, accelerometers, magnetometers, and micromirrors, coupling between vibration modes introduces additional nonlinear effects, often resulting in amplitude imbalance, resonance detuning, and degraded dynamic stability25. To mitigate these nonlinearities, various modeling and compensation approaches have been explored. The electrostatic force is often linearized near small-displacement regions to simplify analytical modeling, although this approximation becomes inaccurate at large oscillation amplitudes where nonlinear stiffness effects dominate26. Conventional proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control remains effective for maintaining amplitude stability and suppressing small disturbances within moderate operating ranges27. However, because PID control relies on linear feedback, its ability to compensate for amplitude–phase coupling and parameter drift arising from electrostatic softening is inherently limited, particularly under varying bias voltages or environmental conditions28. Consequently, more advanced compensation strategies and adaptive or learning-based frameworks have been explored to enhance robustness against these nonlinearities29,30,31.

Recent developments have applied fuzzy-learning and neural-network-assisted controllers to vibratory gyroscopes, enabling real-time adaptation to time-varying parameters while compensating for modeling uncertainties. Xu et al.32 proposed an intermittently dynamic fuzzy learning-based tracking control (IDFL-TC) that dynamically recruits or prunes neurons and intermittently updates learning weights, effectively balancing tracking precision and computational efficiency. Similarly, asynchronous tracking-control (ATC) schemes have demonstrated amplitude stability under partially unknown mode information through adaptive feedback and fuzzy-learning mechanisms33. These data-driven control frameworks substantially enhance robustness and adaptability, providing precise resonance regulation in electrostatically driven MEMS resonators under nonlinear and uncertain operating conditions.

Electrostatic driving control system

For reliable electrostatic operation, MEMS resonators can be driven in open-loop for characterization and simple readout, but precision sensing typically requires closed-loop control to stabilize frequency, amplitude, and phase24,34. Figure 2 summarizes the control architectures of MEMS electrostatic resonator-based sensors: open-loop and closed-loop scheme. Representative closed-loop strategies include self-oscillation loops and phase-locked loops that mitigate thermal and bias drift over time. In block diagram terms, both open- and closed-loop implementations comprise drive generation, the resonator, sensing electrodes, amplification and phase detection, loop filtering, and bias generation stages.

a In an open-loop system the user modulates the input with no feedback. b The self-oscillation system, one of a closed-loop scheme, uses feedback control to satisfy the Barkhausen condition. c The PLL is a closed-loop system that measures phase error and adjusts the drive frequency to keep quadrature

Open-loop operation

Figure 2a shows a block diagram of open-loop control system of resonant MEMS sensors. In open-loop operation, the resonator is driven with a prescribed tone and its response is read out without feedback. This mode is simple, enables rapid frequency sweeps for modal identification and calibration, and is often used to extract small-signal parameters such as quality factor (Q-factor), motional impedance, and electrostatic gain. The main limitation is sensitivity to drift in both frequency and amplitude. Slow variations in temperature, bias voltage, and ambient pressure, together with intrinsic thermoelastic effects, shift the resonance peak and modify the mechanical gain, which directly perturbs the demodulated output in field-sensing use cases35,36,37.

Closed-loop operation

As mentioned above, in electrostatic MEMS resonators, the resonance frequency and scale factor vary with the ambient environment and the drive conditions. Temperature perturbs the device through thermoelastic mechanisms and through packaging effects such as cavity pressure and gas viscosity that modify damping and effective stiffness36. The apparent spring constant also softens with applied bias, so slow drift in the bias or supply translates into frequency and gain drift. To actively compensate these effects, closed-loop architectures regulate one or more resonator state variables to suppress drift and linearize transduction.

A self-oscillation loop sets phase and gain to satisfy the Barkhausen condition so the device oscillates at its natural resonance without a separate timing reference38, as illustrated in Fig. 2b. As the environment changes, the oscillation frequency follows the resonant shift, which makes implementation simple and power efficient but ties stability to the resonator’s own drift. A PLL system, as shown in Fig. 2c, locks an internal numerically controlled oscillator to the resonator’s phase condition so the drive stays in quadrature39. The sensed phase passes through a loop filter to adjust the drive frequency; proper capture and hold-in ranges, loop bandwidth, and phase margin track slow thermal or bias shifts while rejecting high-frequency noise and avoiding peaking. In high-Q shell resonators, nested digital loops for frequency, amplitude, and quadrature reduce inter-loop coupling and improve long-term stability, and the same structure applies to electrostatically driven field-sensing MEMS40.

In closed-loop operation, amplitude regulation stabilizes the scale factor and keeps motion in the linear range, reducing pull-in or compression risk. Automatic gain control (AGC) alongside self-oscillation or a PLL holds a constant amplitude for linear amplitude-readout sensitivity by comparing the envelope to a setpoint and adjusting drive gain38. The AGC response should be slower than the resonator’s amplitude dynamics and the frequency-tracking bandwidth to avoid amplitude–phase coupling and noise peaking; with proper setpoints it prevents front-end saturation and can improve SNR, while frequency-output sensitivity is primarily set by the frequency-tracking loop. In addition, adding thermal-drift41 and bias-drift42 models on top of AGC and frequency tracking system provides feedforward correction and reduces residual drift beyond what feedback alone can achieve.

Signal-to-noise ratio enhancement for MEMS sensors

In resonator-based MEMS sensors, where the mechanical resonance of microstructures is transduced into electrical signals through various coupling mechanisms, the SNR, defined as the ratio between signal strength and noise level, determines the achievable resolution and minimum detectable signal43. As device dimensions continue to shrink, compliant mechanical structures become more susceptible to both intrinsic and extrinsic disturbances, leading to smaller transduced electrical outputs. Consequently, the signal can be buried beneath the noise floor, and the total noise originating from thermomechanical, electronic, and flicker sources collectively define the ultimate sensitivity limit. The total noise floor originates from multiple physical mechanisms, including intrinsic thermomechanical noise, electronic noise from the readout circuitry, and low-frequency flicker noise44,45. These noise components collectively define the ultimate sensitivity limit of the device, particularly under weak-field conditions in external field sensing or during low-amplitude operation. A detailed understanding of these noise sources is therefore essential for improving the overall detection performance of resonant MEMS sensors.

The noise processes that influence resonant MEMS sensors originate from both mechanical and electrical domains. Thermomechanical noise, originating from the intrinsic energy dissipation and Brownian motion of the resonator, defines the fundamental mechanical limit of sensitivity46. Its magnitude is governed by the damping level and ambient temperature, as described by the fluctuation–dissipation theorem47. Electronic noise, which includes Johnson–Nyquist thermal noise from resistive elements, shot noise in bias circuits, and amplifier input noise, arises from the readout and drive electronics48. These components dominate the high-frequency region of the spectrum and can obscure weak resonant signals, particularly when the electromechanical transduction efficiency is low. Flicker noise (1/f noise) becomes significant in the low-frequency regime49,50. Although primarily associated with semiconductor interfaces, it can also manifest in resonant MEMS devices through slow potential fluctuations along conductive paths such as doped silicon regions, metallic electrodes, and interconnecting wires. These fluctuations lead to baseline drift and offset instability. Since these noise sources originate from both the mechanical and electronic domains, effective noise suppression requires comprehensive optimization of the device structure, transduction scheme, and circuit design to minimize the overall noise floor.

Enhancing the SNR requires concurrent optimization of the mechanical structure, electrical readout, and system-level control. Mechanically, improving the Q-factor through symmetric structural design, low-loss materials, and reduced air damping decreases the equivalent thermal force noise and narrows the resonance bandwidth, thereby reducing the overall displacement noise floor within the sensing bandwidth51,52. Electrically, employing low-noise amplifiers, differential or chopper-stabilized readout architectures, and proper grounding and shielding minimizes the voltage and current noise contributions from the readout chain53,54. At the system level, closed-loop amplitude control maintains constant vibration amplitude under varying environmental conditions, while quadrature compensation suppresses phase errors and mitigates parasitic coupling between drive and sense modes. For example, modeling studies on fully closed-loop resonant systems, such as hemispherical resonator gyroscopes under force-to-rebalance operation, have shown that dynamic coupling analysis of driving and detecting loops can effectively suppress interference-induced output errors and maintain stable amplitude tracking55.

By integrating these strategies, resonant MEMS sensors can approach their fundamental noise limits, achieving enhanced SNR and improved resolution even under ambient or weak-field conditions in field-sensing applications. However, higher resolution does not always imply better performance, as it inherently involves trade-offs among sensitivity, bandwidth, accuracy, and response speed, as well as between performance, power consumption, and circuit complexity56,57. Achieving extremely high resolution often demands low-noise electronics, high-resolution analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), and increased power consumption, which together impose greater system complexity and data processing requirements58. Therefore, an optimal resolution should be determined according to the target application, balancing sensitivity, noise performance, and practical constraints. Maintaining this balance is crucial for realizing reliable, energy-efficient, and scalable MEMS sensing systems that can operate effectively in real-world environments.

Magnetic field sensors

Magnetic field sensors, which measure the strength and direction of an external magnetic field, are used in various industrial fields, including position sensing, archaeology, the automotive industry, the medical industry, space research, brain mapping, navigation, and non-destructive diagnosis, depending on their sensing range and resolution59,60,61,62. Existing technologies for magnetic field detection include Hall sensors, search coils, superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs), fluxgate sensors, anisotropic magnetoresistive (AMR) and giant magnetoresistive (GMR) sensors, as well as MEMS-based magnetic field sensors63,64. MEMS magnetic field sensors offer advantages such as small form factor, fast response, and batch-process compatibility. A widely studied category of MEMS magnetic sensors is based on Lorentz force transduction, where an electrical current flowing through a microstructure interacts with an external magnetic field to generate a Lorentz force65,66. This force induces displacement and a shift in the resonant frequency of the vibrating structure, which are measured using various transduction methods, including piezoelectric67,68,69,70,71, capacitive72,73,74, piezoresistive75,76,77, and optical techniques78,79,80,81.

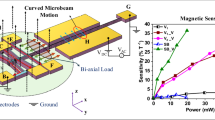

Two representative signal transduction methods in Lorentz-force-based MEMS sensors are amplitude modulation (AM) and frequency modulation (FM). In AM-type sensors, the magnetic field–induced Lorentz force modulates the amplitude of vibration. While straightforward in implementation, this approach often suffers from low SNR under small magnetic fields. In contrast, FM-type sensors rely on resonators driven by comb drives, where the Lorentz force introduces an axial load that shifts the resonant frequency. The external magnetic field strength is inferred from the resulting frequency shift, typically measured by sensing comb capacitors82,83,84,85,86. Techniques such as mechanical leverage can amplify this frequency shift and significantly enhance sensitivity. An improvement of up to 42 times has been reported compared to unamplified designs86.

Despite their utility, Lorentz-force-based MEMS sensors face intrinsic challenges. High excitation currents are typically required to generate measurable displacements or frequency shifts, which increases power consumption and induces Joule heating. This can lead to thermal stress, drift, and mechanical instability in the resonator87. Furthermore, the current-carrying structures require complex electrical routing and readout circuits, which may limit integration density and reliability. To address these limitations, recent studies have explored alternative MEMS magnetic field sensing schemes that decouple actuation and sensing mechanisms. In particular, sensors that combine electrostatic actuation with electromagnetic induction sensing have gained attention as a low-power and thermally stable alternative.

Electrostatically driven MEMS magnetic field sensor using electromagnetic induction

Several recent studies have proposed MEMS magnetic field sensors that use electrostatic actuation and electromagnetic induction sensing87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95. The MEMS sensors driven by electrostatic force have the advantage of low power consumption without self-heating compared with being driven by the Lorentz force. Also, electromagnetic induction sensing provides a direct voltage output, which simplifies the readout circuitry, and inherently exhibits excellent linearity to the applied magnetic field. MEMS magnetic field sensors based on electrostatic force driving and electromagnetic induction sensing have the following advantages over other magnetic field sensing methods. First, a search coil measures only time-varying magnetic fields, whereas electromagnetic induction sensing technology can theoretically detect static and alternating magnetic fields88. Second, unlike magnetoresistive sensors, this technology is free from magnetic hysteresis, as it does not require a unique magnetic material89. Third, the manufacturing processes of MEMS magnetic field sensors are simpler than the complicated production of fluxgate sensors that require the magnetic core and coil to be integrated65. Although the resolution is not higher than that of SQUID, the advantages of MEMS magnetic field sensors are their low power consumption and low cost87.

Figure 3a, b shows schematic diagrams of the sensing mechanism using electrostatic driving and electromagnetic induction sensing for out-of-plane and in-plane magnetic fields, respectively. The area covered by the induction coil within the magnetic field changes by the in-plane87,88,89,90,91 or torsional92,93,94,95 motion of the structure. The structure is moved with electrostatic driving by comb drives or parallel plates. Changes in the induction coil area result in changes in the magnetic flux passing through the induction coil, and an induced electromotive force is generated by the electromagnetic induction principle. Liu et al.87 presented an analytical model of a resonant MEMS magnetic field sensor using electromagnetic induction sensing. The following equation expresses the induced electromotive force (\(\psi\)) of the single induction coil in a static magnetic field.

where \(B\) is the magnetic flux density, \(S\) is the area covered by the induction coil, and \(t\) is the time. As the area covered by the single induction coil changes, the magnetic flux changes, resulting in an induced electromotive force. The following equation expresses the sensitivity (\(U\)) of the magnetic field sensor:

a For in-plane driving, the out-of-plane magnetic field passes through the area enclosed by the coil, which changes due to the lateral motion of the structure. b For torsional driving, the in-plane magnetic field passes through the coil area, which changes as the structure rotates. In both cases, the effective magnetic flux through the coil varies with time, generating an electromotive force via electromagnetic induction

Device modeling can theoretically obtain the sensitivity of an electromagnetic induction-based magnetic field sensor. Because the vibration amplitude of the patterned induction coil on the resonant plate is the same as that of the resonant plate, it can be determined by employing the second-order differential equation of the motion of the resonant plate using the Laplace transform. The induced electromotive force generated in a single induction coil is calculated using the change in the coil area as a function of time from the vibration amplitude of the resonant plate. The induced electromotive force generated in every induction coil is independent, and the total output voltage is obtained by summing the voltages induced in all the coils. Therefore, the sensitivity of the magnetic field sensor can be obtained by dividing the summed induced voltage by the applied magnetic field strength. To enhance sensitivity, it is essential to increase the induced electromotive force, which is proportional to the rate of change of magnetic flux. Because magnetic flux depends on both the area and motion of the coil, sensitivity can be improved by increasing the displacement amplitude and vibration frequency of the resonator. A higher driving voltage strengthens the electrostatic force, resulting in larger resonator displacement and thus greater flux variation. Operating in vacuum reduces air damping, which increases the oscillation amplitude and Q-factor, further increasing the induced voltage. Higher resonant frequency accelerates the flux change rate, leading to stronger output signals. Additionally, increasing the number of coil turns proportionally raises the total induced voltage, thereby enhancing sensitivity. Coil geometry optimization, including turn count and spacing, is also critical to maximize performance while ensuring structural integrity.

Out-of-plane MEMS magnetic field sensing

Wu et al.89 proposed a novel out-of-plane MEMS magnetic field sensor for capacitive driving and electromagnetic induction sensing. Figure 4a shows a schematic of the sensor configuration. The sensor consists of a square plate resonator that contracts and extends symmetrically on four sides, with planar induction coils on its upper surface. The ends of the induction coil were formed outside the resonant plate using the second electrical isolation layer and the second metal layer. The device was fabricated using a cavity-silicon-on-insulator process. In the square extensional (SE) mode, all four sides of the resonant plate contract and extend in phase. The induced electromotive force generated from each part of the induction coil on the resonant plate is summed to detect the output signal.

a Square extensional mode resonator-based magnetic field sensor89. Schematic diagram of a sensor symmetrically resonantly driven by four driving electrodes and its measured frequency response in 60 mT steps (20–320 mT). The induced electromotive force increased linearly with the applied magnetic field. b Dual resonator-based magnetic field sensor90. Schematic diagram of a mechanically coupled dual-micro resonator design and mode shape obtained by finite element method (FEM) simulation. SEM image of a cavity-SOI fabricated sensor and optical image of a vacuum-packaged device. c Double-ended tuning fork (U-shaped) resonator-based magnetic field sensor91. Schematic diagram of a differential readout circuit with a single U-shaped induction coil and measured frequency response at 105 mT under DC voltage actuation (0–10 V, 2 V steps). d 4S beam resonator-based magnetic field sensor88. Schematic diagram showing two S-shaped folded beams and a long beam with symmetrically distributed comb drives. SEM images of the fabricated structure with two-layer coil connection, and frequency response under closed-loop driving

The Q-factor is a physical quantity representing the resonance characteristics. A high Q-factor indicates less energy loss per oscillation cycle relative to the stored energy of the resonator. This resonant characteristic affects the sensitivity and resolution of the sensor by determining the amplitude of vibration at resonance and the sharpness of the frequency response. A higher Q-factor results in larger vibration amplitudes and a narrower bandwidth. In electromagnetic induction sensing, the induced voltage is proportional to the rate of change of magnetic flux through the coil. Since a higher Q-factor yields greater vibrational amplitude at resonance, it produces larger flux variations, thereby enhancing the induced voltage and improving the sensitivity and resolution of the sensor. Compared with the Q-factor of the SE mode resonator without coils, the Q-factor of the coil-integrated magnetic field sensor is reduced from 6000 to 3700 owing to the energy loss caused by the additional mass, such as the oxide layer and the metal layer. The amplitude–frequency response of the sensor was measured in 60 mT steps under ambient atmospheric conditions, over the range of 20–320 mT. The sensor has good linearity and sensitivity of 3 μV/mT. The authors reported analytic modeling to optimize the design of the same structure87. Within design constraints such as the device size and minimum line width resulting from the manufacturing process, the structural parameters such as the length of the resonant plate, length of the driving electrode, width, turn, and spacing of the induction coil were optimized for enhanced sensitivity.

Wu et al.90 presented a method to improve the resonance characteristics such as the Q-factor and sensitivity of magnetic field sensors by utilizing vacuum packaging and mechanically coupled a dual resonator design. Figure 4b presents a schematic of the coupled dual resonator vibrating in the SE mode along with the mode shape obtained by finite element simulation (COMSOL Multiphysics). The dual resonator array increases the induced electromotive force because of the summation of outputs generated from individual resonators and has the effect of boosting the Q-factor. Compared with the previously reported sensor89, the sensitivity of the magnetic field sensor, with a sensitivity of 3 μV/mT in single SE resonating mode, is increased by more than 10 times. Also, vacuum packaging prevents considerable energy dissipation owing to air damping. The SEM image shows the fabricated device before vacuum packaging. The chip-level packaging process entailed eutectic bonding and wire bonding with the magnetic field sensor and ceramic chip. Afterward, the vacuum sealing process was carried out in a high-vacuum furnace with the pressure lowered to 10–6 Torr, and the lid with the getter material was subjected to eutectic bonding. As a result of the vacuum-packaging, the energy dissipation caused by air damping is lowered, thereby increasing the sensitivity and also the Q-factor to 42,000, which is more than 10 times higher than the Q-factor of ~4000 in air. Besides, the vacuum-packaged sensor resonates at a frequency of 4.319 MHz with a sensitivity of 35.92 μV/mT and 47.74 μV/mT, and linearity errors of 0.65% and 1.19% at driving voltages of DC 30 V and 40 V, respectively. As the driving DC bias increased from 30 V to 40 V, the sensitivity increased by more than 1.3 times because of the increased vibration amplitude and velocity of the coil-integrated SE mode resonator.

Zhang et al.91 fabricated an electromagnetic induction-based MEMS magnetic field sensor by using silicon-on-insulator multi-user micro-electromechanical system (MEMS) processes using three photomasks. As shown in Fig. 4c, the sensor is composed of one U-shaped gold induction coil on a pair of clamped-clamped beams using simple fabrication processes without an electrical insulation layer. The U-shaped induction coil resonates with the comb drive attached to both beams. The stiff and bulky SE mode resonator, described in a previous paper89, was fabricated in complex processes requiring six photolithography steps. And, the fabrication method unavoidably requires the deposition and patterning of an insulation oxide interlayer. Although the advantage of the bulk mode is that the influence of air damping on the Q-factor is small, the sensitivity decreases because of the increased stiffness of the resonator. Because the sensor with the structure of a double-ended tuning fork has flexural beams, the excitation voltage was lowered to 5 V, and the sensitivity was increased to 17.7 mV/T. The measured voltage frequency response shows the increase in the induced electromotive force when the DC driving voltage is increased in steps of 2 V in the range 0−10 V at a constant magnetic field strength of 105 mT. The improvement in sensitivity is attributable to the increase in the vibration amplitude as the driving voltage increases. In terms of the sensing accuracy, parasitic feed-through and capacitive motional currents, which cause undesirable offsets in the output, were effectively removed using a differential readout scheme.

As shown in Fig. 4d, Liu et al.88 proposed an out-of-plane magnetic field sensor featuring a 4S beam resonator with 12 turns of two-layer induction coils. The 4S beam resonator has four oscillation elements consisting of two S-shaped folded beams and a long beam. Their magnetic field sensor has a large displacement due to the flexure spring and a large size of 4000 × 4000 μm2. This design improvement increased the sensitivity (1306 mV/μT) of the magnetic field sensor by more than 73 times compared to that of Zhang et al.91. The driving and sensing combs are distributed symmetrically on both sides of the long beam. With the comb drive excited by an electrostatic force, the 4S beam structure vibrates in the contractive-extensional mode at the resonance frequency. An induced electromotive force is generated by the induction coil laid on the structure. An interface circuit with closed-loop self-oscillation was also constructed using the motional current detected from the sensing comb. The mechanical resonance frequency of the resonator is affected by variations in temperature. Therefore, a slight deviation from the drive frequency and a change in the air viscosity caused by the temperature dramatically decrease the sensitivity of the sensor, which is composed of a resonator. Temperature-independent sensitivity would require an interface circuit to be connected to the sensor. The two-layer coils are electrically connected through a common port, insulated by an electrical isolation layer between them, and placed in the same winding direction. This sensor operates at a resonant frequency of 37.63 kHz in air. The sensor has excellent linearity, a linearity error of 0.08%, a Q-factor of 517, and a resolution of 2.57 μT at AC 1.5 Vp and DC 25 V.

In-plane MEMS magnetic field sensing

Detection of the total magnetic field strength and direction requires accurate magnetic field component measurement. Therefore, it is necessary to measure the in-plane as well as the out-of-plane magnetic field. Liu et al.92 proposed an electromagnetic induction-based MEMS magnetic field sensor in a torsional mode for in-plane magnetic field sensing. As shown in Fig. 5a, the seesaw plate (2000 × 2000 × 50 μm3) fabricated by the standard silicon-on-glass process consists of two torsional beams and two layers of aluminum induction coils. Two equivalent parallel-plate driving electrodes electrostatically vibrate torsional motion at a distance of 2.4 μm. When an in-plane magnetic field is applied, the induction coils on the torsionally driven seesaw plate cut the magnetic induction line. The principle of electromagnetic induction generates an induced voltage. The SEM image shows induction coils and the damping holes formed on the seesaw plate. The damping holes (100 × 10 × 52.4 μm3) increase the sensitivity because they reduce the vibrational degradation caused by air damping. Operation of this sensor in air resulted in a sensitivity of 100 mV/mT, a linearity error of less than 0.3%, a high resolution of 25 μT, and low power consumption of less than one microwatt. As the pressure in the experiment decreases, the sensitivity increases rapidly. At 500 Pa pressure, the sensitivity and resolution increased by 41 times and 0.6 μT, respectively, compared with air conditions.

a Torsional plate resonator-based sensor actuated by parallel-plate electrodes92. SEM images show the fabricated structure with damping holes and an integrated induction coil. b Torsional frame resonator-based sensor using vertically interlaced comb drives that enlarge the actuation area and reduce air damping, thereby improving sensitivity and Q-factor. Measured output responses confirm low cross-axis interference and good linearity93. c Two-axis MEMS magnetometer employing an eccentric resonator with a two-layer inductor95. By switching the driving frequency, torsional resonance is excited along either the X- or Y-axis and enables vector detection of in-plane magnetic fields

As shown in Fig. 5b, Liang et al.93 proposed a torsional MEMS magnetic field sensor based on electromagnetic induction using vertically interlaced combs for in-plane magnetic field sensing. The vertically interlaced comb drive, in which fixed and movable comb fingers are alternately arranged on different vertical layers rather than in a single plane, increases the effective actuation area without enlarging the footprint. This configuration also significantly reduces air damping by enabling more efficient airflow between the comb fingers under atmospheric pressure. As a result, both the sensitivity and Q-factor are greatly enhanced. Compared with the performance of the in-plane magnetic field sensor equipped with a parallel-plate electrostatic drive92, the sensitivity of the sensor with the comb-shaped drive increased by 4.9 times and the Q-factor by 81 times at atmospheric pressure. The sensitivity and Q-factor of the former is 100 mV/mT and ~5.3, respectively, whereas the corresponding properties of the latter are 491 mV/mT and ~430, respectively. For accurate three-axis magnetic field sensing, it is essential to minimize cross-interference. The sensor exhibited an X-axis sensitivity of 491 mV/mT, while the sensitivities along the Y- and Z-axes were 4 mV/mT and 7 mV/mT, respectively. The significant difference in the sensitivity of each of these axes indicates low cross-interference. The magnetic field sensor operating at atmospheric pressure shows a linearity error of less than 0.4%, high resolution of 6 μT, and ultralow consumption of 75 nW.

The resonance characteristics of the MEMS magnetic field sensor were also evaluated using electrostatic detection, but this method introduced errors in the resonance frequency and Q-factor measurements due to feed-through effects. A Lorentz fit was therefore applied to obtain the amplitude-frequency response without the appearance of an anti-resonant peak. By contrast, electromagnetic detection allowed the amplitude-frequency response to be measured without feed-through, enabling a more accurate determination of the resonance characteristics. Since the electromagnetic induction-type magnetic field sensor operates in amplitude modulation, the voltage output is directly related to the resonator’s movement in the magnetic field. Differential output measurement further suppressed feed-through crosstalk, providing a clearer observation of the true resonance behavior.

Jung et al.95 developed a two-axis MEMS magnetometer utilizing an electrostatically driven eccentric resonator (1000 × 1000 × 50 μm3) and an electromagnetic inductor, which consists of 52 turns of a two-layer induction coil. Figure 5c illustrates the schematic configuration of the magnetometer, where the eccentric resonator consists of an outer mass and an inner mass. The inner mass is designed with an unbalanced mass, resulting in an eccentric displacement of the center of mass relative to each torsional axis. By switching the resonant frequency, the magnetometer achieves torsional resonance along either the X-axis or the Y-axis using a single-axis comb driver. Consequently, each resonant mode is selectively utilized for detecting the magnetic field along the X- or Y-axis. This monolithic MEMS magnetometer exhibits sensitivities of 21.91 and 57.92 μV/mT in the X- and Y-axis sensing modes, respectively. The output voltage increases with both the applied driving voltage and the magnetic field strength. A higher driving voltage leads to larger vibration amplitudes, which induce greater variation in magnetic flux through the induction coil. The sensor exhibits the in-plane magnetic field sensing characteristics under a driving voltage of 160 V in an atmospheric air environment. By analyzing the measured output voltage, the MEMS magnetometer determines the in-plane magnetic field vector, including both its magnitude and direction.

Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of resonant MEMS magnetic field sensors based on electromagnetic induction published until recently. From this comparison, it is evident that out-of-plane magnetic field sensors primarily focus on single-axis sensing and have demonstrated significant improvements in sensitivity. However, for broader industrial and technological applications, three-axis magnetic field sensing with an extended sensing range is essential. Future research directions can be categorized into three primary areas: enhancing sensitivity, improving resolution, and achieving multi-directional sensing. For in-plane sensing, sensitivity and resolution can be further optimized through analytical modeling of torsional magnetic field sensors, refinement of design parameters, and the implementation of mechanical amplification via multiple mass-spring structures. Multi-directional sensing can be realized either by systematically integrating multiple single-axis magnetic field sensors or by designing sensors with distinct resonance modes that correspond to different sensing directions.

In practice, the required resolution and corresponding sensing range vary widely depending on the target application. For example, geomagnetic navigation and vehicle detection typically demand resolutions in the microtesla range, while biomedical and brain–heart magnetic monitoring require sub-nanotesla or even femtotesla sensitivity. However, the wide gap in reported resolutions among recent MEMS-based magnetic and electric field sensors mainly reflects the varying maturity levels of the underlying device technologies rather than differences in application requirements. In other words, achieving sufficiently high sensitivity and resolution at the sensor level remains one of the key challenges to enabling MEMS devices to be effectively tailored for diverse field-sensing applications.

Addressing these challenges requires improvements at the sensor-design level, particularly for electromagnetic induction-based resonant MEMS magnetic field sensors. In such devices, the induced voltage generated by the dynamic motion of the conductive structure under an external magnetic field is inherently limited by the magnetic flux coupling efficiency, structural vibration amplitude, and coil geometry. Sensitivity can therefore be enhanced by increasing the effective coil turns, optimizing conductor layout for stronger magnetic linkage, and maximizing the mechanical Q-factor through symmetric design and vacuum encapsulation. Meanwhile, thermomechanical and electronic noise can be reduced by employing optimized transduction schemes, differential readout configurations, and low-noise amplification circuits. Additionally, the resonant frequency, device size, and dynamic response speed introduce inherent trade-offs between sensitivity and bandwidth, which must be carefully balanced according to the intended application. Continuous advances in electromagnetic coupling efficiency, low-noise design, and circuit integration are essential to bridge the current resolution gap and expand the applicability of resonant MEMS magnetic field sensors across broader field-sensing domains.

Potential applications

An electrostatically actuated MEMS resonator for magnetic field sensing with electromagnetic induction has the advantages of a small device size and complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor compatibility. The effects of replacing the Lorentz force-based MEMS magnetic field sensor include low power consumption and excellent linearity. The sensing resolution of the MEMS magnetic field sensor of this type is several microtesla, and the sensing range can be expanded by using vacuum packaging94. Applications of this range of magnetic field sensors include rotation and position sensing, navigation, detection and guidance of vehicles, and portable electronics59,60.

In contrast, wearable and implantable magnetic sensors for biomedical monitoring require sub-nanotesla or even femtotesla sensitivity to detect biomagnetic signals such as cardiograms or encephalograms, which currently remain beyond the practical reach of resonant MEMS sensors. Therefore, at the present stage of technological maturity, MEMS-based magnetic sensors are more suitable for external field monitoring (e.g., motion tracking, navigation) rather than direct in vivo biomagnetic detection. Nevertheless, with continuous progress in flux-coupling efficiency, mechanical Q-factor enhancement, and low-noise readout integration, resonant MEMS magnetic sensors are expected to evolve toward sensing platforms capable of capturing biomagnetic signals, thus bridging the gap between external field monitoring and biomedical magnetic sensing. Such development would also open opportunities for cross-domain integration with MEMS electric field sensors, enabling compact, low-power, and multifunctional devices for advanced biomedical and environmental monitoring. From an application perspective, resonant MEMS magnetic sensors also require careful consideration of packaging and mechanical robustness. Mechanical shocks or vibrations can perturb the resonance frequency or degrade the Q-factor, leading to performance drift96. Since these devices are fabricated on rigid substrates and lack structural flexibility, ensuring mechanical isolation and robust packaging is essential for stable operation in wearable or mobile systems.

Navigation and positioning

In the navigation field, MEMS-based inertial measurement units (IMUs) with nine degrees of freedom (DOFs) are used as a personal inertial navigation system (PINS) in which a 3-axis accelerometer, 3-axis gyroscope, and 3-axis magnetic field sensor are integrated into one chip. Location information is obtained by using the 9-DOF IMUs in restricted environments, such as inside buildings and in mountain valleys, where a global navigation satellite system is not available. However, IMUs are generally problematic in that a sudden position error occurs because of low accuracy, offset, and drift. Technology to compensate for this error is shown in Fig. 6a. This technology enables accurate location information to be obtained by using a ground reaction sensor array (GRSA) attached to the shoe97, zero velocity update (ZUPT), and information that was previously mapped98.

a PINS (personal inertial navigation system) using shoes with integrated MEMS-based 9-DOF (degree-of-freedom) IMUs (inertial measurement units) and GRSA (ground reaction sensor array)97. b Smart parking management system (SPMS) architecture provides roadside parking space information using a 3-axis magnetic field sensor99. c Robotic arm with six attitude-measurement MEMS sensors101. d Real-time gesture capture by configuring a data glove system102. e A portable sensor system that uses magnets and magnetic field sensors to monitor the driver’s unbalanced head posture in driving situations103. f Concept and prototype of a wearable intra-oral magnetic sensing system for continuous jaw-motion tracking using small permanent magnets and IMUs with three-axis magnetometers. g Three-dimensional schematic showing the spatial arrangement of the high-voltage direct-current (HVDC) transmission lines and magnetic field sensors104

Vehicle detection and smart parking

In the field of vehicle detection, wireless vehicle detection was used for smart parking management systems (SPMS)99. Measurement of changes in the strength of the magnetic field according to the distance from a ferromagnetic object by using the magnetic field sensor made it possible to classify the arrival time, occupation time, and departure time of the vehicle100. Figure 6b shows that the SPMS architecture on the roadside identifies the presence of a vehicle and uses a magnetic field sensor to provide parking space information via a cloud server.

Motion tracking and posture monitoring

Figure 6c shows the robotic arm and the six attitude-measurement units (AMUs) mounted on each link. In the field of position sensing, the multi-joint angle of the revolute serial manipulator can be estimated using a low-cost MEMS magnetic, angular rate, and gravity sensor101. As shown in Fig. 6d, motion is captured using a data glove attached to 18 inertial and magnetic measurement units (IMMUs) worn on the hand. The motion is demonstrated immediately via a virtual model on a PC102. The micro-control unit attached to the data glove samples, collects, and calculates the raw data measured by the IMMUs and transmits the data to an external device via Bluetooth. The PC determines the gestures in real time based on the transmitted results and can remotely control the target to pick up, move, lift, and drop bottles using the hand of the robotic arm. Figure 6e shows an experimental system that monitors the driver’s posture in a driving practice situation. A magnetic field sensor attached to the driver’s neck and a small magnet detects when the posture of the head becomes unbalanced to prevent potential car accidents103. The magnetic field sensor measures the magnetic field along each axis according to the driver’s posture in various driving situations, such as checking the road conditions to the left and right, checking the side mirrors on the left and right, and driving straight ahead. Considering the various available machine-learning methods, an algorithm was used to train a neural network to more accurately recognize the driver’s current head posture based on the measured magnetic field data. Figure 6f illustrates a wearable intra-oral magnetic sensing system developed for continuous jaw-motion tracking in bruxism monitoring. The system integrates small permanent magnets with IMUs that include three-axis magnetometers to continuously register jaw position and motion trajectories. A dual-magnetometer configuration compensates for background magnetic fields, and trigonometric modeling enables the reconstruction of both translational and rotational motion. This approach demonstrates the feasibility of compact, low-power, wearable intra-oral devices capable of precise and continuous jaw-motion monitoring.

Voltage monitoring for high-voltage direct-current transmission lines

Figure 6g illustrates a non-contact voltage monitoring concept for high-voltage direct-current (HVDC) transmission lines based on hybrid electric and magnetic coupling. In this method, the voltage induced by the external electric field is correlated with the actual line voltage through magnetic-field-assisted calibration and optimization104. Such a sensing concept demonstrates the feasibility of DC voltage monitoring without direct electrical contact, providing a safe and scalable solution for large-area power networks. Although the reported implementation utilizes magnetoresistive sensors, similar voltage-monitoring functionality could be realized using electrostatically actuated MEMS magnetometers with electromagnetic-induction sensing. Replacing the discrete magnetoresistive components with an integrated MEMS platform would enable further miniaturization, lower power consumption, and seamless CMOS compatibility, making it suitable for array-based distributed monitoring in HVDC systems.

Electric field sensors

Electric field sensors are devices capable of detecting a wide range of electric fields, from those in the atmosphere and around the human body to those generated by electronic devices and high-voltage systems. With their versatility, these sensors have been utilized in diverse applications, including non-destructive diagnosis of electronic devices, biomedical fields, and motion sensing. From this perspective, MEMS electric field sensors have also been developed for a number of years. Methods for electric field detection using micromachined devices are based on various techniques, including electro-optical methods105,106,107,108, steered electron detection109, piezoelectric resonance110, and measurements of capacitance changes resulting from electrostatic driving induced by an external field111,112. However, these methods often require additional power sources, which inevitably compromise the inherent miniaturization advantage of MEMS sensors. Moreover, the measured signals obtained through some of these methods are unstable and inaccurate with a low SNR. Moreover, these electric field sensors face structural and material limitations, making monolithic integration with other electronic systems difficult. In an effort to address the aforementioned issues, MEMS electric field sensors have been developed that offer a stable and linear response using simple fabrication processes. Incorporating these aspects, Wang et al. have previously provided an overview of resonant MEMS electric field sensors113. Instead, this paper classifies electrostatically driven resonant electric field sensors based on their target sensing dimensions and presents a structured overview of their capabilities.

Design and deployment of MEMS electric field sensors should consider the target application. For atmospheric monitoring, fair-weather fields are on the order of 100 V/m114. For diagnostics around HVDC or high-voltage alternating current (HVAC) assets, where events such as icing and corona onset occur, prioritize a wide dynamic range of 0–50 kV/m115,116. While advancing resolution and sensitivity remains important, broader utility also calls for on-chip multi-dimensional sensing that resolves unknown vector fields in hardware, together with structural cross-axis suppression.

Electrostatically driven MEMS electric field sensor using electrostatic induction

Electrostatically driven MEMS resonators for electric field sensing adopt the principle of “field mills.” The field mill is a device used to sense electric fields at macroscale level, and it operates on the principle of electrostatic induction117,118. As shown in Fig. 7, the field mill consists of a grounded shield (or shutter) that is connected to a rotating motor, with sensing electrodes positioned beneath the shutter. Upon exposure to an electric field, a surface charge forms on the sensing electrodes, and the area exposed to the electric field is changed by rotating the grounded shield. The induced current is generated by changes in the surface charge. The surface charge density, total surface charge, and induced current on the sensing electrode are expressed by the following equations:

As the grounded shutter (or shield) rotates at a constant speed, the charge on the A and B electrodes change in opposite directions. The currents induced by these charges are generated in opposite directions. The field mill detects electric fields with high sensitivity by sensing the potential difference between the A and B electrode sets

where \(E\) is the applied external electric field, and \(A\) is the area of the surface exposed to the electric field. The rotating shield is grounded to prevent distortion of the electric field that needs to be detected, and a pair of sensing electrodes (denoted A and B in Fig. 7) are separately designed on the same plane and are exposed to the electric field in opposite directions. This design simultaneously induces positive and negative changes in the charge of electrodes A and B, respectively. At this time, currents in the opposite direction are induced in the two sensing electrodes according to Eq. (5). By converting the currents to voltages using current-to-voltage converters, the field mill achieves higher sensitivity in measuring the electrical potential difference through differential sensing. This electric field detection method, utilizing electrostatic induction, offers the advantages of a highly linear response and a wide detection range.

Based on intuitive sensing principles and linear response, electrostatic induction using MEMS electric field sensors has been widely studied. However, unlike macroscale systems, achieving fully rotating motion in MEMS devices is challenging for field mill applications. To address this limitation, linear and torsional resonant driving have been applied to MEMS electric field sensors. Through lateral resonant driving of the grounded shield, the exposure area of the sensing electrodes to the electric field continuously changes, generating electrostatically induced current in the sensing electrodes.

Various alternative driving schemes in MEMS, such as electrothermal119,120,121,122 and piezoelectric123 methods, have been explored to achieve resonant actuation of the grounded shield. However, these methods present certain challenges, including high power consumption, complex fabrication processes, and structural limitations that result in non-IC compatible devices. Consequently, electrostatic driving, with its advantages of low power consumption and IC-compatibility, is the most commonly employed method for MEMS electric field sensors based on electrostatic induction.

One-dimensional MEMS electric field sensing

Horenstein et al.124 designed and fabricated the first MEMS electric field sensors based on electrostatic resonance driving and electrostatic induction. This study focused on the design of a MEMS electric field sensor featuring a micro-aperture within the grounded shield. As shown in Fig. 8a, the grounded shield and the sensing electrode at the bottom face each other in a vertically parallel arrangement. The movable shuttle mass, acting as a grounded shield, has a micro-aperture (5 × 10 µm2) positioned within it and is anchored with folded spring structures. This grounded shield is driven with a resonant frequency of 7.6 kHz using electrostatic comb-drive actuators on both sides. The principle of electric field detection is illustrated in Fig. 8b. As the area of the sensing electrode exposed to the electric field changes, charge is induced via electrostatic induction. Despite a high driving voltage of 60 V, the device exhibits low sensitivity of 35 µV/(kV/m) due to the small change in the exposed area.

a Schematic representation of the MEMS electric field sensor with a micro-aperture in the movable shuttle mass (grounded shield)124. b Diagram depicting electrostatic induction caused by the relative motion between the micro-aperture and the sensing electrode. The grounded shield with an aperture is electrostatically driven by the comb drive. The electric field density passing through the micro-aperture repeatedly changes, generating induced charge on the sensing electrode. The current induced by the charge variance is converted into voltage, and the sensor measures the electric field by reading the voltage. c Schematic of the MEMS electric field sensor based on electrostatic driving and electrostatic induction126. Grounded shield with slits and sensing electrodes facing each other in the vertical direction. d At sensing electrode set 1, the charge increases, and positive output current is induced as the area exposed to the electric field is expanded. The opposite occurs at sensing electrode set 2. The sensitivity of the sensor is doubled by obtaining the differential outputs of sensing electrodes set 1 and 2

Peng et al.125,126 proposed the sensor design illustrated in Fig. 8c to enhance sensitivity by increasing the area exposed to the electric field and introducing differential sensing127. In this design, the grounded shield and sensing electrodes are positioned parallel to each other. The grounded shield contains multiple slits spaced apart, and comb drives resonantly actuate the shield. These slits in the shield maximize the change in the area exposed to the electric field. As shown in Fig. 8d, two large area sensing interdigital electrodes (IDEs) are placed on the bottom layer, referred to as sensing electrodes 1 and 2, and a shield with slits is actuated on the left and right in linear resonant mode by comb drives. The charge on sensing electrode 1 increases as the exposed area increases, generating a positive current. Conversely, the charge on sensing electrode 2 decreases at the same time. This arrangement enables an increase in both the SNR and sensitivity by applying differential sensing of these opposite electrical potentials.

This design, in which the sensing electrodes and the grounded shield are vertically aligned, facing each other, requires complex fabrication processes. In several studies, the sensing electrodes and the shield were integrated into the same layer in a lateral arrangement to simplify the fabrication of MEMS electric field sensors. To reduce the number of fabrication steps, Lee et al.128, Zhu et al.129, and Peng et al.130 developed MEMS electric field sensors using bulk micromachining techniques with silicon-on-insulator (SOI) wafers. Figure 9a–c, respectively, presents the structural arrangement of the laterally aligned sensing electrodes and shield in an isometric view, a side view, and top-view SEM images. The sensing electrodes, grounded shield, and comb drive are incorporated into the device layer of an SOI wafer. The two sensing electrodes were arranged in opposite directions. The electric field distribution formed around the sensing electrodes changed according to the movement of the grounded shield, thereby generating charge variation. As shown in Fig. 9d, the sensing electrodes generate opposite currents based on the direction of the charge. The sensor detects the output voltage differentially by reading the voltage-converted signal between the two sensing electrodes. Peng et al.130 implemented a self-oscillating closed-loop control scheme with AGC to automatically track the resonance frequency and secure high detection resolution and SNR, achieving a Q-factor of 31034 and resolution of 50 V/m. To further probe this sensing principle, Fang et al.131 conducted a numerical analysis of the electric field distribution on the surface of the sensing electrodes when the grounded shield and sensing electrodes were placed laterally. The same structure was used to measure the synthetic electric field from atmospheric ion flow and a high-voltage system132,133 as well as to demodulate AC/DC hybrid fields in a power system134.

a Schematic representation of an electric field sensor structure in which the shield and sensing electrodes are arranged laterally on the same device layer130. b Cross-sectional view of an electric field sensor fabricated by a bulk-micromachined SOI wafer. c SEM images of the sensor. d Increasing the electric field density on the sensing electrode induces a positive current and vice versa. e Schematic of a MEMS electric field sensor using electrostatic induction135. The sensitivity of the sensor increases by extending the amount of charge variation with the addition of coplanar combs. f SEM images of the fabricated MEMS electric field sensor

Using the same fabrication process and similar lateral structure, Yang et al.135 improved sensitivity by increasing the capacitance between the grounded shield and sensing electrodes. In this study, coplanar comb electrodes were implemented by incorporating an offshoot structure. Figure 9e presents a schematic of the MEMS electric field sensor with coplanar comb electrodes, and Fig. 9f shows an SEM image of the device. This coplanar comb design enhances electrostatic induction, resulting in greater charge formation compared to that of a purely lateral comb. Consequently, a stronger induced current, higher sensitivity, and a resolution of 40 V/m were achieved. They also demonstrated through computational simulations that the coplanar comb structure increases charge formation.

The electric field sensors mentioned above show that integrating the sensing and shield electrodes on the same layer128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135 has the advantage of simplifying the fabrication process. However, these sensors suffer from their relatively low sensitivity. To address this issue, Wang et al.136 tried to increase the sensitivity of the MEMS electric field sensor by employing out-of-plane torsional resonance for the grounded shield. Figure 10 illustrates the structure and sensing principle of this sensor. Unlike previously developed MEMS electric field sensors driven by lateral comb drives, this design uses torsional resonant actuation through electrostatic forces between a pair of large-area electrodes (1900 × 500 µm2) on the bottom and the shield, as shown in Fig. 10a, b. Figure 10c illustrates the sensing mechanism of the sensor. Vertical displacement between the shield and sensing electrodes, caused by resonant electrostatic driving, generates both charge and induced current. Makihata et al.137 demonstrated that the efficiency of the induced current increases when the shield undergoes vertical angular movement rather than lateral movement using a multi-resonance mode MEMS device. This improved induced current efficiency enhances the sensitivity of this MEMS electric field sensor achieving 4.82 mV/(kV/m) as shown in the plot of Fig. 10d136. For applying the sensitivity enhancement mechanism based on torsional driving of grounded shield while simplifying the sensor structure and fabrication process, Jung et al.138 introduced a MEMS electric field sensor in which the comb-drive actuator with starting electrode, shield, and sensing electrodes were laterally arranged. Figure 10e, f shows schematic and an SEM image of this MEMS electric field sensor. The sensor places the driving electrodes, sensing electrodes, and a torsional shutter on the same layer, while designing the sensing electrodes with a high aspect ratio to maximize the area exposed to the electric field during resonant driving. With this design, as depicted in Fig. 10g, the MEMS sensor achieved a response of 3.219 mV/(kV/m).

a Structure of the electric field sensor with out-of-plane torsional driving via an electrostatic force between the driving electrode at the bottom and the grounded shield136. b SEM images of the MEMS electric field sensor with a torsion-driven shield. c Movement of the grounded shield results in vertical displacement between the shield and the sensing electrode. At this time, the distribution of the electric field reaching the sensing electrode changes. This generates an induced current on the basis of changes in the charge. d Response plot of the MEMS electric field sensor. e A schematic illustration of the MEMS electric field sensor with torsional comb driving138. f A SEM image of the sensor showing lateral integration of sensing and driving electrodes. g Sensor responses under different driving voltages

Multi-dimensional MEMS electric field sensing

In the previously described MEMS electric field sensors, the electric field was measured by applying it in a single direction. However, in many scenarios, such as in autonomous driving, the direction of the electric field measurement is unknown. Thus, a need has arisen to measure a multi-dimensional electric field. To address this challenge, MEMS sensors capable of detecting multi-directional electric fields have been developed.

Wang et al.139 developed a two-dimensional electric field sensor on a single chip driven by a single electrostatic actuation, as shown in Fig. 11a–d. This electric field sensor features a symmetrical structure on all four sides. Each side consists of a central rotary comb drive, an external sensing element, and a grounded shield-sensing electrode pair. The grounded shield is rotationally driven by the four comb drives. The sensing element pairs labeled 1–3 and 2–4 in Fig. 11a detect electric fields in the X- and Y-directions, respectively. In addition, as shown in Fig. 11c, two sensing elements in a directional pair produce signals of equal amplitude with opposite phase, enhancing sensitivity through differential sensing. The magnitude and direction of the two-dimensional electric field can be determined by the vector summation of the X-axis electric field (EX) and Y-axis electric field (EY). With this mechanism, sensitivities of 0.675 mV/(kV/m) and 0.689 mV/(kV/m) were achieved on the X- and Y-axes, respectively. To perform 2D sensing with only a single actuation, electrostatic rotary comb driving is used instead of linear movement along the X- and Y-axes. In this situation, cross-interference from the electric fields along the other axis inevitably appears (the red line connecting the dots on the left and black line connecting the squares on the right in Fig. 11d).

a Schematic illustration of a MEMS 2D electric field sensor consisting of four pairs of driving and sensing parts139. b SEM images of the fabricated electric field sensor. c Simulated induced charge for the four sensing elements versus the incident angle of an external electric field. d Results of the X-axis (left) and Y-axis (right) electric field measurement. The black squares and red dots are the responses of the X- and Y-axis sensors, respectively. Both of these results are affected by cross-interference with other axes, requiring additional calibration. e Structure of the MEMS 3D electric field sensor with single driving input consisting of rotary comb drives in four directions140. The sensor has X- and Y-sensing components on the outside and Z-axis sensing components at the center. f SEM images of the sensing and driving parts of the sensor. g Measured output voltage as a function of the electrostatic field: X-axis (left), Y-axis (middle), and Z-axis (right). As seen above, cross-interference also occurs when the electric field of all axes is detected

Ling et al.140 developed a MEMS sensor for three-dimensional (3D) electric field sensing driven by single electrostatic resonance. A Z-axis sensing function was added by placing a pair of grounded shield-sensing electrodes at the center. This sensor, depicted schematically in Fig. 11e, has four side symmetrical rotary comb drives and external sensing comb electrodes and a central component for Z-axis sensing. Figure 11f presents SEM images of the fabricated sensor’s sensing and driving parts. Figure 11g shows the sensing characteristics of the electric field along each axis. This MEMS 3D electric field sensor has a relatively large footprint area (1100 × 1100 µm2) and volume. Therefore, the sensor requires high-voltage electrostatic driving of DC 80 V and AC 3.5 V to drive its large mass. Its sensitivities are 0.136, 0.121, and 0.101 mV/(kV/m) for the X-, Y-, and Z-axes, respectively. However, undesirable cross-interference inevitably occurs among the axes as it is a 3D electric field sensor driven by single rotary resonance.

This interference results in signals from other axes reaching half the intensity of those from the target axis139,140. Within these single chip architectures, traditional mathematical decoupling calibration methods can be applied to separate axis components and compensate cross-interference141,142. To further exclude cross-axis interference, statistical estimators such as recursive least-squares and maximum-likelihood can be used to identify bias, scale, and misalignment parameters143. Beyond these statistical model-based approaches, data-driven algorithm based decoupling has also been explored: for example, genetic-algorithm (GA) optimization can identify decoupling parameters that minimize cross-axis error across the operating envelope142, and multi-output support vector machine (SVM) regression can map measured vectors directly to the true 2D and 3D field with improved robustness144. Together, these algorithmic pathways offer a practical route to compact multi-axis electric field sensors while avoiding footprint growth and complex post-fabrication processes.

To address cross-axis interference inherent to on-chip electric field sensors, Ling et al.145 designed a new electric field sensing device utilizing physical integration of three separate electric field sensors to minimize cross-interference with the other axes. In this study, one-dimensional (1D) MEMS electric field sensors were fabricated to measure the lateral electric field, as shown in Fig. 12a. The three 1D electric field sensors were then attached to a printed circuit board (PCB, 3 × 3 cm2), and they were manually combined in an orthogonal arrangement like Fig. 12b. The driving voltage was DC 20 V and AC 1 V, and three sensors were designed to operate at same resonant frequencies. All three sensors are driven by a single input with the same voltage and frequency. The 3D electric field sensor manufactured in this way detects 3D electric fields with very low cross-interference, as shown in Fig. 12c.

a Schematic of the 1D MEMS electric field sensor for use as a 3D electric field sensor145. These 1D sensors are physically integrated perpendicularly. b Optical image of the 3D electric field sensing device with three 1D sensors combined on a PCB and placed perpendicularly to each other. c Electric field detection results. Cross-interference with the detection results of other axes is significantly reduced compared to the multi-dimensional electric field sensors based on single driving input. d Schematic of the 3D electric field sensor folded to combine three 1D electric field sensors after combination146. e Process of bonding three 1D sensors using polymer hinge bonding after on-wafer fabrication. f As a result of electric field detection, cross-interference on the Z-axis detection increased owing to structural limitations

However, this manually combined electric field sensor is bulky and requires a laborious assembly process with low reliability. Ling et al.146 therefore developed a MEMS electric field sensor by fabricating three 1D electric field sensors simultaneously on a wafer-scale to facilitate simple assembly. As seen in Fig. 12d, three electric field sensors are connected by micro-hinges made from a photosensitive polyimide (PSPI) film. These hinges enable precise manufacturing without assembly misalignment. The resonant frequencies of the three sensors were intentionally designed to be similar, resulting in 2270, 2245, and 2210 Hz for the X-, Y-, and Z-axes, respectively. This sensor has three 1D electric field sensors arranged in a self-assembled isosceles right triangle configuration for 3D electric field detection (Fig. 12e). However, as shown in Fig. 12f, the electric field in the Z-axis causes cross-interference during sensing in the X- and Y-axes directions.

Table 2 summarizes the electrostatic induction utilized by the electrostatically driven MEMS electric field sensors discussed above. The summary includes the driving conditions and sensing performance of these sensors. Due to the linearity of their sensing mechanism, they exhibit linear measurement characteristics with a linearity error of less than 5.5%. In addition, multi-dimensional electric field detection with MEMS sensors has been attempted over time. However, from a sensing performance perspective, the overall sensitivities of these multi-dimensional electric field sensors are low. As a result, electric field sensing circuits require voltage amplifiers. The minimum reported sensing resolution is 40 V/m, indicating that further improvement in sensitivity and resolution is necessary for reliable electric field detection and broader applications.

Electrostatically driven MEMS electric field sensor using mode localization