Abstract

In recent years, many researchers have made a continuous effort to develop new and efficient meta-heuristic algorithms to address complex problems. Hence, in this study, a novel human-based meta-heuristic algorithm, namely, the learning cooking algorithm (LCA), is proposed that mimics the cooking learning activity of humans in order to solve challenging problems. The LCA strategy is primarily motivated by observing how mothers and children prepare food. The fundamental idea of the LCA strategy is mathematically designed in two phases: (i) children learn from their mothers and (ii) children and mothers learn from a chef. The performance of the proposed LCA algorithm is evaluated on 51 different benchmark functions (which includes the first 23 functions of the CEC 2005 benchmark functions) and the CEC 2019 benchmark functions compared with state-of-the-art meta-heuristic algorithms. The simulation results and statistical analysis such as the t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and Friedman test reveal that LCA may effectively address optimization problems by maintaining a proper balance between exploitation and exploration. Furthermore, the LCA algorithm has been employed to solve seven real-world engineering problems, such as the tension/compression spring design, pressure vessel design problem, welded beam design problem, speed reducer design problem, gear train design problem, three-bar truss design, and cantilever beam problem. The results demonstrate the LCA’s superiority and capability over other algorithms in solving complex optimization problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The optimization technique involves finding a scenario that minimises or maximises an objective function while fulfilling a predetermined set of constraints. This case is known as the optimal solution, and it is often explored through an exponential collection of candidate solutions requiring highly expensive execution time. Meta-heuristic approximation techniques have been developed to help with this practical challenge. Even though these problem-solving methods cannot guarantee that the solution is optimal, they are quite capable of providing solutions that are close to optimal1,2,3,4,5,6. Meta-heuristic algorithms use exploitation and exploration, which represent intensity and diversity, as their two methods for determining the optimal solution. The growth of meta-heuristic algorithms has been influenced by a variety of natural phenomena, including animals, insects, wildlife, birds, living things, plants, biomedical laws, chemical reactions, physics laws, human activities, game mechanics, and other natural biological processes. In general, meta-heuristic algorithms may be divided into five categories: evolutionary-based optimization algorithms, swarm-based optimization algorithms, chemistry and physics-based optimization algorithms, game-based optimization algorithms, and human-based optimization algorithms.

The modelling of biological sciences and genetics and the use of evolutionary operators like natural selection are the basis of evolutionary-based optimization algorithms7. One of the first evolutionary-based optimization algorithm, the genetic algorithm (GA)8, has been developed using selection, crossover, and mutation sequence operators and a model of the reproductive process. Another popular evolutionary-based optimization algorithm called differential evolution (DE)9 has been developed as a powerful and quick method to solve problems in continuous spaces and has a strong capacity to optimize non-differentiable nonlinear functions. Some other algorithms in this group, such as cultural algorithms (CAs)10, Biogeography-Based Optimizer (BBO)11, invasive tumor growth (ITGO)12, and learner performance behaviour (LPB)13. The development of swarm-based optimization algorithms is focused on simulating the natural behaviours of creatures such as animals, insects, ocean animals, plants, and other living things. One of the most commonly used swarm-based algorithms is Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)14, which takes its inspiration from the reasonable behaviour of fish and birds. The Grey Wolf optimization (GWO)15,16,17 has been created using hierarchical leadership behaviour modelling as well as grey wolf hunting tactics. Ant colony optimization (ACO)18 was created by modelling the behaviour of ant swarms in order to determine the shortest route between a food source and a nest. The humpback whales use of bubble nets for hunting served as inspiration for the Whale optimization algorithm (WOA)19. Tunicate Swarm algorithm (TSA)20, Crow Search Algorithm (CSA)21, Raccoon optimization algorithm (ROA)22, Tree seed algorithm (TSA)23, Marine predators algorithm (MPA)24, Capuchin search algorithm (CapSA)25, Chameleon Swarm algorithm (CSA)26, and Aquila optimizer (AO)27 are other swarm-based algorithms28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35.

Based on the modelling of several physics phenomena and laws, optimization algorithms with such a physics-based algorithm have been developed. The Simulated Annealing (SA)36, one of the first algorithms in this category, was inspired by the modelling of the annealing process in metallurgical cooling and melting processes. The water cycle algorithm (WCA)37 simulates the evaporation of water from the ocean, cloud formation, rainfall, river creation, and overflow of water from pits, all of which are inspired by the natural water cycle. A gravitational search algorithm (GSA)38 has been developed as a result of simulations of the gravitational force that objects exert on one another at various distances. Other physics-based algorithms are atom search optimization (ASO)39, multi-verse optimizer (MVO)40, Electromagnetic field optimization (EFO)41, nuclear reaction optimization (NRO)42, optics inspired optimization (OIO)43, Equilibrium optimizer (EO)44, Archimedes Optimization Algorithm (AOA)45, and Lichtenberg Algorithm (LA)46. Chemistry-based algorithms have been developed with chemical reactions as inspiration. One of the most famous chemistry-based algorithms is chemical-reaction-inspired meta-heuristic for optimization47. Chemical reaction optimization (CRO)48 is a recently developed meta-heuristic for optimization that takes inspiration from the nature of chemical reactions. A natural process of changing unstable molecules into stable molecules is called a chemical reaction. Another chemistry-based algorithm is artificial chemical reaction optimization algorithm (ACROA)49.

Game-based algorithms have been created using simulations of the rules governing various sports and the actions of players, trainers, and other participants. The Volleyball premier league (VPL)50 algorithm’s major concept has been to create modelling contests for the volleyball league, while the football game-based optimization (FGBO)51 algorithm’s main idea was to create modelling competitions for the football league. The Puzzle Optimization Algorithm (POA)52 was developed mostly as a result of the players’ strategy and talent in creating puzzle components. The primary inspiration for the Tug-of-War Optimization (TWO)53 technique was the players’ collective effort throughout the game. The introduction of human-based algorithms is based on the mathematical simulation of various human activities that follow an evolutionary process. The most well-known human-based algorithm is called teaching-learning-based optimization (TLBO)54, and it has been created by simulating the conversation and interactions between a teacher and students in a classroom. Doctor and patient optimization (DPO)55 algorithm has been made with interactions between doctors and patients, such as preventing illness, getting check-ups, and getting treatment, in mind. Creating Poor and rich optimization (PRO)56 has been primarily motivated by the economic activities of the rich and poor in society. In order to be successful, human mental search (HMS)57 has been created by simulating human behaviour on online auction marketplaces. Other human-based algorithms are Tabu Search (TS)58,59, Imperialist Competitive Algorithm (ICA)60, colliding bodies optimization (CBO)61, Mine Blast Algorithm (MBA)62, seeker optimization algorithm (SOA)63, group counseling optimization (GCO)64,65 algorithm, harmony search (HS)66, League Championship Algorithm (LCA)67, Coronavirus herd immunity optimizer (CHIO)68, and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (AFT)69.

In recent years, meta-heuristic algorithms are applied for solving complex problems in different applications such as optimization of weight and cost of cantilever retaining wall70, multi-response machining processes71, symbiosis organisms search for global optimization and image segmentation72, human social learning intelligence73, nanotubular halloysites in weathered pegmatites74, numerical optimization and real-world applications75, convergence analysis76, higher Dimensional Optimization Problems77, non-dominated sorting advanced78, Lagrange Interpolation79. LCA is quite different from the existing meta-heuristic algorithms although it belongs to the category of human-based meta-heuristics. The major difference between LCA and them is its particular human-based background. LCA is inspired by observing how mothers and children prepare food. Another important difference is exploration and exploitation. The proposed LCA algorithm works in two phases such as (i) children learn from their mothers and (ii) children and mothers learn from a chef. The exploration is established through Phase 1 of the algorithm when the children learn from their mothers. In the same way, the exploitation is established through Phase 2 of the algorithm, when the children and mother learn from the chef. Therefore, considering these mentioned factors, there are significant differences between LCA and the existing meta-heuristic algorithms. Table 1 shows the comparative assessment between the proposed LCA algorithm and other meta-heuristic algorithms that have been analyzed in terms of algorithm search mechanisms.

The existing meta-heuristic algorithms have some flaws, concerns, and issues. For example, the Harris Hawk Optimization (HHO) algorithm83 performs well at solving standard benchmark problems while failing miserably at complex problems such as CEC 2017 and real-world problems. As a result, in order to solve complex problems and functions, the performance of this algorithm needs to be improved. The poor and rich algorithm (PRO)56 was recently developed and configured to perform well on a few simple and old test functions while failing to solve new and complex test functions such as CEC 2017. As a result, in order to solve complex problems and functions, the algorithm has to be improved. The mechanism of well-known algorithms such as the grey wolf optimizer (GWO)15 and the whale optimization algorithm (WOA)19 is very similar, with the main difference being the search range. Here, a critical question arises: What is required to offer and develop new algorithms in the presence of well-known algorithms like those stated above? According to the No Free Lunch (NFL)87 theorem, no optimization algorithm can solve all optimization problems. According to the NFL, an algorithm’s ability to successfully address one or more optimization problems does not guarantee that it will do so with others, and it may even fail. As a result, it is impossible to say that a particular optimization algorithm is the best approach for all problems. New algorithms can always be developed that are more effective than current algorithms at solving difficult optimization problems. The NFL invites researchers to be inspired to create new optimization algorithms that are better able to address difficult optimization problems. The ideas described in the NFL theorem inspired the authors of this paper to propose a new optimization algorithm namely the Learning Cooking Algorithm (LCA).

In every optimization algorithm, exploration and exploitation play the most important role. So, keeping this in mind, this paper proposes a new human-based algorithm namely the LCA algorithm to maintain a proper balance between exploration and exploitation among optimization algorithms. The LCA algorithm mimics two phases: (i) children learn from their mothers and (ii) children and mothers learn from a chef. The exploration is established through Phase 1 of the algorithm when the children learn from their mothers. For each child, the corresponding mother is chosen by the greedy selection mechanism. This phase helps the algorithm explore the large search space. In the same way, the exploitation is established through Phase 2 of the algorithm, when the children and mother learn from the chef. The chef acts as the global best solution and directs the other swarm particles i.e. the children and mothers to move towards it. The 51 different benchmark functions (which include the first 23 functions of the CEC 2005 benchmark functions) and the CEC 2019 benchmark functions are employed to evaluate the LCA’s capability. Seven well-known algorithms, two top-performing algorithms, and eight recently developed algorithms for solving optimization problems are compared to the performance of the proposed LCA algorithm. This algorithm has also been used to solve seven optimal design problems in order to evaluate the LCA for solving real-life engineering problems. The structure of the paper is designed as follows: “Learning cooking algorithm” describes the inspiration for the Learning Cooking Algorithm (LCA) and the mathematical model for the LCA. In “Simulation studies and results”, simulation studies, results, and discussion are presented. The performance of LCA in solving engineering design problems is evaluated in “LCA for engineering optimization problems”. Conclusions and suggestions for further study of this paper are provided in “Conclusion”.

Learning cooking algorithm

In this section, the learning cooking algorithm (LCA) is proposed, followed by a discussion of its mathematical modelling.

Inspiration

Cooking is the process of exposing food to heat. All of the methods constitute cooking, regardless of whether the food is baked, fried, sauteed, boiled, or grilled. According to the evidence, our ancestors began cooking over an open fire some 2 million years ago. Although devices like microwaves, toasters, and stovetops are extensively utilized, some foods are still cooked over an open flame. There are numerous ways to cook, but the majority of them have their origins in the past. These include boiling, steaming, braising, grilling, barbecuing, roasting, and smoking. Steaming is a more recent innovation. Different cooking techniques require varying levels of heat, moisture, and time. First of all, without being cooked, certain foods are not safe to eat. Cooking not only heats food but also has the potential to eliminate dangerous microorganisms. Because they are more likely to carry bacteria while they are raw, meats must be cooked to a specific temperature before eating. Cooking is a learning process in which a beginner (a child) learns to cook from the mother, and then children and mothers learn to cook from the cooking expert by watching television, YouTube, and other social media platforms. This study “Learning Cooking Algorithm,” is divided into two phases: (i) children learn from their mothers and (ii) children and mothers learn from a chef. This idea is similar to meta-heuristic algorithms, in which the problem’s best candidate solution is selected as the algorithm’s final output after multiple initial candidate solutions are improved through an iterative process.

Mathematical model of LCA

LCA is a population-based optimization algorithm that includes cooking learners (children), mothers, and chefs. LCA members are candidate solutions to the problem, as it is modelled by a population matrix in Eq. (1). Equation (2) is used to randomly initialize these members’ positions at the beginning of implementation.

where C is the LCA population, \(C_i\) is the \(i{th}\) candidate solution, \(c_{i,j}\) is the value of the \(j^{th}\) variable determined by the \(i{th}\) candidate solution, the value N represents the size of the LCA population, m is the number of problem variables, the value of rand is chosen at random from the range \(\left[ 0,1\right] \), the upper and lower limits of the \(j{th}\) problem variable are denoted as \({UB}_j\) and \({LB}_j\), respectively. Here, in the LCA algorithm the food items represent the problem variables. The children and mothers try to learn different types of cuisines such as Mexican, Italian, Indian, American cuisines from the chefs around the world.

The objective function values are represented by the vector in Eq. (3).

where the objective functions are represented by the vector F and \(F_i\) represented the of objective function delivered by the \(i{th}\) candidate solution.

The values for the objective function are the most important things used to judge the quality of candidate solutions. On the basis of comparisons of the values of the objective function, the member of the population with the best value is referred to as the “best member of the population (Cbest).” Each iteration improves and updates the candidate solutions, so the best member must also be updated. The methodology used to update candidate solutions is the main difference between meta-heuristic optimization algorithms. In LCA, candidate solutions are updated in two main phases: (i) children learn from their mothers and (ii) children and mothers learn from a chef.

Phase 1: children learn from their mothers (exploration)

The first stage of the LCA update is based on the choice of the mother by the children and then the teaching of cooking by the selected mother to the children (Fig. 1). The selection of mothers is done by choosing a number of the best members from the whole population. The number of mothers is denoted by \(N_{MO}\) which is decided using the formula \(N_{MO} =\lfloor 0.1\cdot N\cdot (1-\frac{t}{T} )\rfloor \). After choosing the mother and trying to learn how to cook, children in the population will move to different places in the search space. This will improve the LCA’s exploration capabilities in the global search for it and the identification of the optimal location. The exploratory capability of this algorithm is therefore demonstrated by this stage of the LCA. Equation (4) says that the \(N_{MO}\) members of the LCA population are chosen as mothers by comparing the values of the objective function at each iteration.

where MO is the matrix of mothers, \({MO}_{i}\) is the \(i{th}\) mothers, \({MO}_{i,j}\) is the \(j{th}\) dimension, and \(N_{MO}\) is the number of mothers, t represents the current iteration and the maximum number of iterations is T.

The new location for each member is first determined by using Eq. (5) in accordance with the mathematical modelling of this LCA phase. Equation (6) shows that the new location takes the place of the old one if the value of the objective function increases.

where \(C_{i}^{P1}\) is the new calculated status for the \(i{th}\) candidate solution based on the first phase of LCA, \(c_{i,j}^{P1}\) is its \(j{th}\) dimension, \(F_{i}^{P1}\) is its objective function value, \(I_{1}\) is a number chosen at random from the range of \(\{1,2\}\), and the value of \(rand_{1}\) is a random number between [0, 1], \(MO_{{k_i}}\), where \(k_i\) is chosen at random from the set \(\{1,2,\cdots ,N_{MO} \}\), represents a randomly selected mother to learn the \(i{th}\) member, \(MO_{{k_i},{j}}\) is its \(j^{th}\) dimension, and \(F_{MO_{k_i}}\) is its objective function value.

Phase 2: children and mother learn from chef (exploitation)

The second stage of the LCA update is based on the children and their mother selecting the chef, followed by watching a YouTube video to learn the chef’s style of cooking (Fig. 2). The selection of chefs is done by choosing a number of the best members from the mother population. The number of chefs is denoted by \(N_{Cf}\) which is decided using the formula \(N_{Cf} =\lfloor 0.1\cdot N_{MO}\cdot (1-\frac{t}{T})\rfloor \). The population members will move to the local search after selecting the chef and learning about their various cooking techniques. The \(N_{Cf}\) members of the LCA population are chosen as chefs in each iteration based on a comparison of the values of the objective function, as given in Eq. (7). This phase demonstrates the power of LCA to exploit global search.

where Cf is the matrix of chefs, \({Cf}_{i}\) is the \(i{th}\) chefs, \({Cf}_{i,j}\) is the \(j{th}\) dimension, t represents the current iteration and the maximum number of iterations is T.

In order to represent this concept mathematically, the new location for each member is determined using Eq. (8). By Eq. (9), this new position replaces the previous one if it enhances the objective function’s value.

where \(C_{i}^{P2}\) is the new calculated status for the \(i^{th}\) candidate solution based on the second phase of LCA, \(c_{i,j}^{P2}\) is its \(j^{th}\) dimension, \(F_{i}^{P2}\) is its objective function value, \(I_{2}\), \(I_{3}\), are a numbers randomly chosen from the set \(\{1,2\}\), the values of \(rand_{2}\), \(rand_{3}\) are a random numbers between [0, 1], \(Cf_{k_i}\), where \(k_i\) is chosen at random from the set \(\{1,2,\cdots ,N_{Cf} \}\), represents a randomly selected chef to learn the \(i^{th}\) member and mother, \({Cf_{{k_i},{j}}}\) is its \(j^{th}\) dimension, and \(F_{Cf_{k_i}}\) is its objective function value.

Repetition procedure, pseudo-Code of LCA and LCA flow chart:

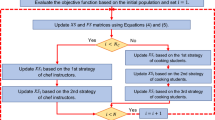

An LCA iteration is completed after the population members have been updated in accordance with the first and second stages. The algorithm entered the following LCA iteration with the updated population. To complete the maximum number of repetitions, the updation procedure is performed in accordance with the first and second phase stages and in accordance with Eqs. (4) to (9). The best candidate solution that has been recorded during the execution of LCA on the given problem is presented as the solution when LCA has been fully implemented. The proposed LCA algorithm pseudocode is shown in Algorithm 1, and Fig. 3 shows its flowchart.

The computational complexity of LCA

The computational complexity of LCA is discussed in this subsection. The computational complexity of the preparation and initialization of LCA for the problem with the number of members equal to N and the problem with the number of decision variables equal to m is equal to \(O(N \times m)\). The LCA members are updated in two stages during each iteration. As a result, the computational complexity of the LCA update processes is \(O(2N\times m\times T)\), where T is the maximum number of algorithm iterations. As a consequence, the total computational complexity of LCA is \(O(N\times m\times (1+2T))\).

Simulation studies and results

This section looks at how well the LCA performs in applications involving optimization and how it provides the most effective solutions to these types of problems. In LCA, fifty-one different Benchmark functions (which includes the first 23 functions of the CEC 2005 benchmark functions)88 and ten CEC 2019 benchmark functions89 are used. The performance of the LCA algorithm is compared with well-known algorithms, top-performance algorithms, modified algorithms, and newly developed algorithms, such as PSO14, TSA20, SSA80, MVO40, GWO15, WOA19, GJO81,90, LSHADE91, CMAES92, IGWO93, MWOA94, TLBO54, MTBO86, BWO82, HHO83, MGO84, and SCSO85 in order to evaluate the efficiency of the LCA results. For each of the optimization algorithms under evaluation, the size of the population, maximum iterations, and the number of function evaluations (NFEs) are set at 30, 1000, and 30,000, respectively, with 20 independent runs for each function. Table 2 lists the parameter values for each algorithm. The details of the 51 test functions and CEC 2019 test functions are described in Tables 3 and 4. For validation, a parametric and non-parametric statistical analysis such as the mean value of the fitness function (average), standard deviation (std), best, worst, median, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, t-test, rank, Friedman test, and convergence curve of algorithms are used. Optimization algorithms base their performance ranking criteria on the t-test value. The NA denotes “Not Applicable” which means that the equivalent algorithm result cannot be compared with other algorithm results. The experiments are performed on Windows 10, Intel Core i3, 2.10GHz, 8.00 GB RAM, and MATLAB R2020b.

Measurements of performance

-

Mean value

The average value represents the mean of the best results obtained by an algorithm over various runs, and it can be determined as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} Mean=\frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^N {A_{i}}, \end{aligned}$$(10)where \(A_{i}\) denotes the best-obtained solution from \(i^{th}\) run and N represents 20 independent runs.

-

Standard deviation (Std)

The standard deviation is determined to examine whether an algorithm can generate the same best value in multiple runs and to examine the repeatability of an algorithm’s outcomes, which can be calculated as follows:

$$\begin{aligned} Std = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum _{i=1}^N (A_i -Mean)^2}, \end{aligned}$$(11) -

Best

The lowest of the results received from different runs:

$$\begin{aligned} Best=Min_{1\le i\le N} {A_{i}^*}. \end{aligned}$$(12) -

Worst

The highest of the results received from different runs:

$$\begin{aligned} Worst=Max_{1\le i\le N} {A_{i}^*}. \end{aligned}$$(13) -

Median

The ordered data’s middle value.

-

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test is used to determine whether two samples come from the same population.

-

Rank

Optimization algorithms base their performance ranking criteria on the t-test value.

-

t-test

A statistical test like a t-test is employed to estimate the significant differences between the proposed method with respect to other meta-heuristics. These are calculated as follows;

$$\begin{aligned} t-value=\frac{Mean_{1}-Mean_{2}}{\sqrt{\frac{Std_{1}^2+Std_{2}^2}{N}}} , \end{aligned}$$(14)where \(Mean_{1}\), \(Mean_{2}\), \(Std_{1}\), and \(Std_{2}\) be the mean and standard deviation for the two algorithms, respectively.

Comparison results of LCA with well-known & top-performing algorithms for 51 benchmark functions

The comparison results of 51 functions are shown in Tables 5, 6 and 7, where LCA delivers the global optimal results of all the algorithms on 38 functions and is competitive on the other functions. In LCA, 44 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. In PSO, 17 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Moreover, LCA and PSO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F27, F35, F36, \(F40-F46\), and F50. In TSA, 6 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Furthermore, LCA and TSA provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F35, F40, F41, and F44. In SSA, 6 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Furthermore, LCA and SSA provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F27, F43, and F46. In MVO, 10 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Moreover, LCA and MVO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F24, F30, F37, F43, F44, and F46. In GWO, 12 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Moreover, LCA and GWO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F24, F27, F35, F37, \(F40-F42\), F44, and F46. In WOA, 14 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Furthermore, LCA and WOA provide the same best average results on some functions such as F9, F11, F16, F18, F24, F27, F28, F35, F37, F40, F41, F43, F44, and F46. In GJO, 13 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Moreover, LCA and GJO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F9, F11, F16, F18, F24, F27, F28, F35, F37, \(F40-F42\), and F44. In LSHADE, 27 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Furthermore, LCA and LSHADE provide the same best average results on some functions F16, F18, \(F22-F24\), F27, F29, F30, \(F34-F37\), \(F40-F42\), \(F44-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). In CMAES, 11 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Furthermore, LCA and CMAES provide the same best average results on some functions F11, F16, \(F21-F24\), F27, F35, F36, and F46. The results of the implementation of LCA and nine competitor algorithms on the functions F1 to F15 are reported in Table 5. The simulation results show that LCA has been able to achieve global optimality in optimizing benchmark functions such as F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, F8, F9, F11, F14, and F15. Furthermore, LCA performed better in optimizing benchmark functions F7, F10, F12, and F13. The optimization results show that LCA is the best of all the optimizers when compared to handling the functions from F1 to F15. The optimization results of the LCA, and nine competitor algorithms on the functions from F16 to F30 are presented in Table 6. The simulation results show that LCA has been able to achieve global optimality in optimizing the benchmark functions \(F16-F18\), \(F21-F25\), and \(F27-F30\). Furthermore, LCA performed worst in optimizing the benchmark functions F19, F20, and F26. According to the simulation results, PSO has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark functions F19, and F26. The global optimal in the function F19 is provided by SSA. And then MVO algorithm provides the global optimal in the functions F19, and F20. The optimization results of the LCA algorithm and nine competitor algorithms on the functions from F31 to F51 are presented in Table 7. The simulation results show that LCA has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark functions \(F31-F37\), \(F40-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). Furthermore, LCA performed worst in optimizing the benchmark functions F38, F39, F47, and F48. According to the simulation results, PSO has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing benchmark functions F34, F36, F47, and F48. Analysis of the simulation results shows that the LCA algorithm has superior and much more competitive performance than the other nine compared algorithms.

Comparison results of LCA with recent algorithms for 51 benchmark functions

The comparison results of 51 functions are shown in Tables 8, 9 and 10, where LCA delivers the global optimal results of all the algorithms on 38 functions and is competitive on the other functions. In LCA, 44 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. In IGWO, 22 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Moreover, LCA and IGWO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F23, F24, F27, F31, \(F35-F37\), \(F40-F42\), \(F44-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). In MWOA, 7 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Furthermore, LCA and MWOA provide the same best average results on some functions such as F9, F24, F28, F35, F40, F41, and F44. In TLBO, 20 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Furthermore, LCA and TLBO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F10, F11, F16, F18, F24, F26, F27, F31, \(F35-F37\), \(F40-F42\), \(F44-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). In MTBO, 17 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Moreover, LCA and MTBO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F16, F18, F24, F26, F27, \(F35-F37\), \(F40-F42\), \(F44-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). In BWO, 18 out of 51 benchmark function’s average results are the best. Moreover, LCA and BWO provide the same best average results on some functions such as F1, F3, \(F8-F11\), F16, F18, F24, F25, F28, F32, F33, F35, F37, \(F40-F42\), and F44. In HHO, 15 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Furthermore, LCA and HHO provide the same best average results on some functions such as \(F8-F11\), F24, F35, \(F40-F42\), \(F44-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). In MGO, 27 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Moreover, LCA and MGO provide the same best average results on some functions such as \(F8-F11\), F16, F18, F23, F24, F27, F28, F30, F31, \(F34-F37\), \(F40-F47\), and \(F49-F51\). In SCSO, 11 out of 51 benchmark functions provide the best average results. Furthermore, LCA and SCSO provide the same best average results on some functions \(F9-F11\), F24, F28, F31, F35, \(F40-F42\), and F44. The results of the implementation of LCA and eight competitor algorithms on the functions F1 to F15 are reported in Table 8. The simulation results show that LCA has been able to achieve global optimality in optimizing benchmark functions such as \(F1-F6\), F8, F9, F11, F14, and F15. Furthermore, LCA performed better in optimizing benchmark functions F7, F10, F12, and F13. The optimization results show that LCA is the best of all the optimizers when compared to handling the functions from F1 to F15. The optimization results of the LCA, and eight competitor algorithms on the functions from F16 to F30 are presented in Table 9. The simulation results show that LCA has been able to achieve global optimality in optimizing the benchmark functions \(F16-F18\), \(F21-F25\), and \(F27-F30\). Furthermore, LCA performed worst in optimizing the benchmark functions F19, F20, and F26. According to the simulation results, the TLBO has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark function F19 and F26. The MTBO has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark function F26. Then the SCSO has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark function F19. The optimization results of the LCA algorithm and eight competitor algorithms on the functions from F31 to F51 are presented in Table 10. The simulation results show that LCA has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark functions \(F31-F37\), \(F40-F46\), and \(F49-F51\). Furthermore, LCA performed worst in optimizing the benchmark functions F38, F39, F47, and F48. According to the simulation results, IGWO has been able to provide the global optimal in optimizing the benchmark functions F38, F39, F47, and F48. Analysis of the simulation results shows that the LCA algorithm has superior and much more competitive performance than the other eight compared algorithms.

Convergence analysis for 51 benchmark functions

The convergence curve represents a relation between the fitness function value and the number of iterations. The search agent explores the search area and deviates rapidly in the beginning stage of the optimization process. The main objective behind the convergence analysis is to understand the behaviour and graphical representation of the proposed method. Figure 4 shows the convergence curves of LCA with well-known algorithms for different test functions. From Fig. 4 it is observed that the proposed method LCA converges faster among the benchmark functions except for F14, F17, F18, F26, and F36. Moreover, the LCA technique has a larger effect on the convergence of the other algorithms, especially compared with the PSO, TSA, SSA, MVO, GWO, WOA, and GJO. Figure 5 shows the convergence curves of LCA with recent algorithms for different test functions. From Fig. 5 it is observed that the proposed method LCA converges faster among the benchmark functions except for F14, \(F17-F20\), F27, F30, F31, F37, F43, and F46. Moreover, the LCA technique has a larger effect on the convergence of the other algorithms, especially compared with the IGWO, MWOA, TLBO, MTBO, BWO, HHO, MGO, and SCSO. Thus, it is proven with the improvements that the proposed LCA can achieve a higher search accuracy and faster convergence.

Comparison results of LCA with well-known & top-performing algorithms for CEC 2019 test functions

In this subsection, we discuss the efficiency of the proposed LCA and compare it with well-known algorithms and top-performing algorithms. Table 11 demonstrates the evaluation results of competitive algorithms. In comparison to PSO, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1, and CEC19-2 . In comparison to TSA, LCA produces better results in 5 functions, such as CEC19-1, CEC19-2, CEC19-3, CEC19-6, and CEC19-8. In comparison to SSA, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1 and CEC19-3. In comparison to MVO, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1 and CEC19-2. In comparison to GWO, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1 and CEC19-6. In comparison to WOA, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1 and CEC19-7. In comparison to GJO, LCA produces better results in 3 functions, such as CEC19-1, CEC19-3, and CEC19-6. In comparison to LSHADE, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1 and CEC19-3. In comparison to CMAES, LCA produces better results in 4 functions, such as CEC19-1, CEC19-2, CEC19-3, and CEC19-6. Hence, the proposed LCA algorithm has a good exploitation ability and a good spatial exploration ability, which makes it possible for it to handle optimization problems successfully.

Comparison results of LCA with recent algorithms for CEC 2019 test functions

In this subsection, we discuss the efficiency of the proposed LCA and compare it with recent algorithms. Table 12 demonstrates the evaluation results of competitive algorithms. In comparison to IGWO, LCA produces better results in 3 functions, such as CEC19-1, CEC19-3, and CEC19-6 . In comparison to MGWO, LCA produces better results in 2 functions, such as CEC19-1 and CEC19-3. In comparison to TLBO, LCA produces better results in 3 functions, such as CEC19-1, CEC19-3, and CEC19-6. In comparison to MTBO, LCA produces better results in 3 functions, such as CEC19-1, CEC19-3, and CEC19-6. In comparison to BWO, LCA produces better results in 5 functions, such as CEC19-2, CEC19-3, CEC19-6, CEC19-7, and CEC19-8. In comparison to HHO, LCA produces better results in 1 function, such as CEC19-3. In comparison to MGO, LCA produces better results in 1 function, such as CEC19-3. In comparison to SCSO, LCA produces better results in 1 function, such as CEC19-3. Hence, the proposed LCA algorithm has a good exploitation ability and a good spatial exploration ability, which makes it possible for it to handle optimization problems successfully.

Convergence analysis for CEC 2019 benchmark functions

The main objective behind the convergence analysis is to understand the behaviour and graphical representation of the proposed method. Figure 6 shows the convergence curves of LCA with well-known algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. From the Fig. 6, it is observed that the proposed method LCA converges faster among CEC 2019 benchmark functions except for \(CEC19-2\), \(CEC19-3\), \(CEC19-4\), \(CEC19-5\), \(CEC19-5\), \(CEC19-5\), \(CEC19-6\), \(CEC19-7\), \(CEC19-8\), \(CEC19-9\), and \(CEC19-19\). Moreover, the LCA technique has a larger effect on the convergence of the other algorithms, especially compared with the PSO, TSA, SSA, MVO, GWO, WOA, and GJO. Figure 7 shows the convergence curves of LCA with recent algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. From the Fig. 7 it is observed that the proposed method LCA converges faster among CEC 2019 benchmark functions except for \(CEC19-2\), \(CEC19-3\), \(CEC19-4\), \(CEC19-5\), \(CEC19-5\), \(CEC19-5\), \(CEC19-6\), \(CEC19-7\), \(CEC19-8\), \(CEC19-9\), and \(CEC19-19\). Moreover, the LCA technique has a larger effect on the convergence of the other algorithms, especially compared with the IGWO, MWOA, TLBO, MTBO, BWO, HHO, MGO, and SCSO.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test95 is used to provide statistical analysis of LCA performance in comparison to competing algorithms. Based on a statistic known as the p value, The Wilcoxon rank-sum test evaluates if the superiority of one approach over another is statistically significant. The results of performing the Wilcoxon rank-sum test to LCA are compared to each of the competing algorithms. The results show that LCA is statistically better than a similar competitor algorithm in any case where the p value is estimated to be less than 0.05. The symbol P denotes the hypothesis. Two-tailed t-tests have been used to compare different statistical results at a significance level of 0.05. The t values are provided with the help of mean values and standard deviations. A negative t value indicates that the statistical outcomes of the LCA optimization errors are significantly less, and vice versa. The corresponding t value is highlighted if the difference is a statistically significant error. The symbols w/t/l denote that LCA wins in w functions, ties in t functions, and loses in l functions. Table 13 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test results for LCA versus well-known and top-performing algorithms for 51 benchmark functions. Table 14 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test results for LCA versus recent algorithms for 51 benchmark functions. Table 15 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test results for LCA versus well-known and top-performing algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. Table 16 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test results for LCA versus recent algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. Table 17 shows the average run time of algorithms for the 23 benchmark functions. Table 18 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test validation for LCA versus well-known and top-performing algorithms for 51 benchmark functions. Table 19 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test validation for LCA versus recent algorithms for 51 benchmark functions. Table 20 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test validation for LCA versus well-known and top-performing algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. Table 21 shows the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and t-test validation for LCA versus recent algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. The statistical results of the optimization errors demonstrate that LCA has a much superior overall performance when compared with the other algorithms.

In this experiment, the Friedman test96,97 is used to rank the performance of the algorithms under evaluation. This test ranks the value of each algorithm from lowest to greatest and evaluates if there is a significant difference between LCA and the comparative optimization algorithms. Table 22 shows the over-rank report of LCA with well-known and top-performing algorithms for 51 benchmark functions. Table 23 shows the over-rank report of LCA with recent algorithms for 51 benchmark functions. Table 24 shows the over-rank report of LCA with well-known and top-performing algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. Table 25 shows the over-rank report of LCA with recent algorithms for CEC 2019 benchmark functions. According to Table 22, LCA has the greatest overall capacity to solve these challenging problems, with a mean rank of 2.1372. According to Table 23, LCA has the greatest overall capacity to solve these challenging problems, with a mean rank of 1.9019. The results of the Friedman test again prove the superiority of LCA over the other considered optimizers.

Informed consent

I confirm that all these pictures belong to ourselves (the authors), and the people pictured have provided their consent for their likeness to be used in an online, open-access scientific journal. In the case of those under 16 years of age, consent has been provided by the parent/legal guardian.

LCA for engineering optimization problems

The capability of LCA to provide the best solution for real optimization applications is discussed in this section. For this purpose, LCA and competing algorithms have been employed in seven real-life problems, such as tension/compression spring design, pressure vessel design problem, welded beam design problem, speed reducer design problem, gear train design problem, three-bar truss design, and cantilever beam problem. The performance of the LCA algorithm is compared with well-known and most recent algorithms such as PSO14, TSA20, SSA80, MVO40, GWO15, WOA19, GJO81, IGWO93, MWOA94, TLBO6, MTBO86, BWO82, HHO83, MGO84, and SCSO85 in order to evaluate the efficiency of the LCA results.

Tension/compression spring design problem

The tension/compression spring design problem is explained in98, and the goal is to reduce the weight of a tension/compression spring. This problem is constrained by minimum deflection, shear stress, surge frequency, outer diameter limits, and design factors. The design factors are the mean coil diameter D, the wire diameter d, and the number of active coils N. Figure 8 illustrates the spring and its properties. The mathematical formulation of this design problem is as follows,

Table 26 show the comparison results of the tension/compression spring design problem. Table 27 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the tension/compression spring design problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results shows that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables of (5.566E-02, 4.591E-01, 7.194E+00) and an optimal solution of 1.250E-02. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Pressure vessel design problem

The idea is to produce a pressure vessel design with the least cost. Figure 9 illustrates the pressure vessel and the design parameters. This problem has four variables: shell thickness (\(T_s\)), head thickness (\(T_h\)), inner radius (R), and length of the cylindrical section excluding the head (L). This design problem is mathematically deposited as follows:

Table 28 show comparison results of the pressure vessel problem. Table 29 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the pressure vessel problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results show that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables of (1.406E+00, 2.712E+00, 6.178E+0, and 2.609E+01) and an optimal solution of 5.886E+03. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Welded beam design problem

A popular welded beam design99 is given in Fig. 10 to examine the demonstration of LCA in the engineering area. The goal is to discover the optimal design factors for reducing the total manufacturing cost of a welded beam exposed to bending stress (\(\sigma \)), shear stress (\(\tau \)), beam end deflection (\(\delta \)), the bar’s buckling load (\(P_c\)) and other constraints. This problem has four variables: weld thickness (h), bar length (l), height (t), and thickness (b). This design problem is mathematically deposited as follows:

Table 30 show the comparison results of the pressure vessel problem. Table 31 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the pressure vessel problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results show that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables of (1.922E-01, 6.087E+00, 9.008E+00, and 2.087E-01) and an optimal solution of 1.715E+00. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Speed reducer design problem

The speed reducer100, is a crucial component of the gearbox in mechanical systems and has a wide range of uses. In this optimisation problem, the weight of the speed reducer has to be lowered with 11 constraints (Fig. 11). Seven variables make up this problem, such as b, m, x, \(l_1\), \(l_2\), \(d_1\), and \(d_2\). This design problem is mathematically deposited as follows:

Table 32 show the comparison results of the speed reducer design problem. Table 33 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the speed reducer design problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results show that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables of (3.502E+00, 7.000E-01, 2.517E+01, 8.230E+00, 8.300E+00, 3.811E+00, and 5.457E+00) and an optimal solution of 2.990E+03. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Gear train design problem

Sandgren proposed the gear train design issue as an unconstrained discrete design problem in mechanical engineering101. The purpose of this benchmark task is to reduce the gear ratio, which is defined as the ratio of the output shaft’s angular velocity to the input shaft’s angular velocity. The design variables are the number of teeth of the gears \(\eta _{A} (z_{1})\), \(\eta _{B} (z_{2})\), \(\eta _{C} (z_{3})\),and \(\eta _{D} (z_{4})\), and Fig. 12 illustrates the 3D model of this problem. The mathematical formulation of the gear train design problem is as follows,

The optimization technique involves finding a scenario that minimises or maximises an objective function while fulfilling a predetermined set of constraints. This case is known as the optimal solution, and it is often explored through an exponential collection of candidate solutions requiring highly expensive execution time. Meta–heuristic approximation techniques have been developed to help with this practical challenge. Even though these problem–solving methods cannot guarantee that the solution is optimal, they are quite capable of providing solutions that are close to optimal1,2,3,4,5,6. Meta–heuristic algorithms use exploitation and exploration, which represent intensity and diversity, as their two methods for determining the optimal solution. The growth of meta–heuristic algorithms has been influenced by a variety of natural phenomena, including animals, insects, wildlife, birds, living things, plants, biomedical laws, chemical reactions, physics laws, human activities, game mechanics, and other natural biological processes. In general, meta–heuristic algorithms may be divided into five categories: evolutionary–based optimization algorithms, swarm–based optimization algorithms, chemistry and physics–based optimization algorithms, game–based optimization algorithms, and human–based optimization algorithmTable 34 show the comparison results of the gear train design problem. Table 35 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the gear train design problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results show that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables (5.593E+01, 1.435E+01, 3.146E+01, and 5.593E+01) and an optimal solution of 0.000E+00. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Three-bar truss design problem

Figure 13 illustrates a three-bar planar truss construction in this scenario. The volume of a statically loaded 3-bar truss must be reduced while stress (\(\sigma \)) constraints on each truss member are maintained. The aim is to find the best cross-sectional areas, \(A_{1} (z_{1})\) and \(A_{2} (z_{2})\). The mathematical formulation of this design problem is as follows,

Table 36 show the three-bar truss design problem comparison results. Table 37 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the three-bar truss design problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results show that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables of (0.792680179 and 0.397975679) and an optimal solution of 263.86. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Cantilever beam design problem

This problem belongs to the category of concrete engineering problems102. By maximizing the hollow square cross-section specifications, the overall weight of a cantilever beam is minimized. Figure 14 illustrates how the cantilever’s free node is subjected to a vertical force while the beam is tightly supported at one end. Five hollow square blocks of constant thickness make up the beam; their heights (or widths) are the decision variables, while the thickness remains constant (in this case, 2/3). The mathematical formulation of this design problem is as follows:

Table 38 show the cantilever beam problem comparison results. Table 39 shows the statistical results of optimization algorithms for the cantilever beam problem compared with different algorithms in terms of the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median. The results show that LCA has provided the solution to this problem with optimal values for variables of (5.627E+00, 5.392E+00, 4.439E+00, 3.433E+00, and 3.204E+00) and an optimal solution of 1.3289. The simulation results show that the LCA is superior when compared with other competitor algorithms by providing a better solution and better statistical indicators.

Conclusion

This study has introduced a novel human-based meta-heuristic algorithm, namely the Learning Cooking Algorithm, to mimic the food preparation style in our daily lives. The strategies of LCA were mathematically designed in two phases: (i) children learn from their mothers, and (ii) children and mothers learn from a chef. These phases act like the exploration and exploitation mechanisms, which are vital for any meta-heuristic algorithm. The efficiency of the proposed LCA has been tested on 51 benchmark functions and CEC 2019 benchmark functions, and the results have been compared with eminent and top-performing algorithms. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed algorithm LCA provides a better outcome to an optimization problem by preserving the proper balance between exploration and exploitation. The execution of the LCA algorithm to address seven real-world engineering problems reveals the superior performance of the proposed algorithm. Although LCA has delivered satisfactory results in solving the problems addressed in this paper, there are certain limitations to this approach in solving some multi-modal separable and multi-modal non-separable functions from the 51 benchmark functions and some functions from the CEC 2019 benchmark functions. In future work, this paper suggests several modifications, such as the inclusion of adaptive inertia factors and levy flight distribution, to improve the performance of the proposed LCA algorithm. It also recommends future research on developing a binary and multi-objective version of the LCA algorithm.

Data availability

Data and MATLAB code used during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

References

Yang, X.-S. Nature-inspired Metaheuristic Algorithms (Luniver press, 2010).

Abbasian, R., Mouhoub, M. & Jula, A. Solving graph coloring problems using cultural algorithms. In FLAIRS Conference (2011).

Shil, S. K., Mouhoub, M. & Sadaoui, S. An approach to solve winner determination in combinatorial reverse auctions using genetic algorithms. In Proc. of the 15th annual conference companion on Genetic and evolutionary computation, 75–76, https://doi.org/10.1145/2464576.2464611 (2013).

Mohapatra, P., Das, K. N. & Roy, S. An improvised competitive swarm optimizer for large-scale optimization. Soft Comput. Probl. Solv. SocProS 2017(2), 591–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1595-4_47 (2018).

Mohapatra, P., Das, K. N., Roy, S., Kumar, R. & Dey, N. A novel multi-objective competitive swarm optimization algorithm. Int. J. Appl. Metaheur. Comput. (IJAMC) 11, 114–129. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJAMC.2020100106 (2020).

Gopi, S. & Mohapatra, P. Fast random opposition-based learning aquila optimization algorithm. Heliyonhttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e26187 (2024).

Mohapatra, P., Roy, S., Das, K. N., Dutta, S. & Raju, M. S. S. A review of evolutionary algorithms in solving large scale benchmark optimisation problems. Int. J. Math. Oper. Res. 21, 104–126. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMOR.2022.120340 (2022).

Mirjalili, S. & Mirjalili, S. Genetic algorithm. Evolut. Algorithms Neural Netw. Theory Appl.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93025-1_4 (2019).

Price, K., Storn, R. M. & Lampinen, J. A. Differential Evolution: A Practical Approach to Global Optimization (Springer Science & Business Media, 2006).

Maheri, A., Jalili, S., Hosseinzadeh, Y., Khani, R. & Miryahyavi, M. A comprehensive survey on cultural algorithms. Swarm Evolut. Comput.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2021.100846 (2021).

Simon, D. Biogeography-based optimization. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput.https://doi.org/10.1109/TEVC.2008.919004 (2008).

Tang, D., Dong, S., Jiang, Y., Li, H. & Huang, Y. Itgo: Invasive tumor growth optimization algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2015.07.045 (2015).

Rahman, C. M. & Rashid, T. A. A new evolutionary algorithm: Learner performance based behavior algorithm. Egypt. Inform. J.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eij.2020.08.003 (2021).

Kennedy, J. & Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proc. of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks, vol. 4, 1942–1948, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNN.1995.488968 (1995).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Adv. Eng. Softw. 69, 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2013.12.007 (2014).

Chandran, V. & Mohapatra, P. Enhanced opposition-based grey wolf optimizer for global optimization and engineering design problems. Alex. Eng. J. 76, 429–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2023.06.048 (2023).

Sarangi, P. & Mohapatra, P. Modified hybrid gwo-sca algorithm for solving optimization problems. Int. Conf. Data Anal. Comput.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-3432-4_10 (2022).

Dorigo, M., Maniezzo, V. & Colorni, A. Ant system: Optimization by a colony of cooperating agents. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. B (Cybern.) 26, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1109/3477.484436 (1996).

Mirjalili, S. & Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 95, 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2016.01.008 (2016).

Kaur, S., Awasthi, L. K., Sangal, A. & Dhiman, G. Tunicate swarm algorithm: A new bio-inspired based metaheuristic paradigm for global optimization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 90, 103541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103541 (2020).

Hussien, A. G. et al. Crow search algorithm: Theory, recent advances, and applications. IEEE Access 8, 173548–173565. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3024108 (2020).

Koohi, S. Z., Hamid, N. A. W. A., Othman, M. & Ibragimov, G. Raccoon optimization algorithm. IEEE Access 7, 5383–5399. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2882568 (2018).

Gharehchopogh, F. S. Advances in tree seed algorithm: A comprehensive survey. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 29, 3281–3304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-021-09698-0 (2022).

Faramarzi, A., Heidarinejad, M., Mirjalili, S. & Gandomi, A. H. Marine predators algorithm: A nature-inspired metaheuristic. Expert Syst. Appl. 152, 113377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113377 (2020).

Braik, M., Sheta, A. & Al-Hiary, H. A novel meta-heuristic search algorithm for solving optimization problems: Capuchin search algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05145-6 (2021).

Braik, M. S. Chameleon swarm algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for solving engineering design problems. Expert Syst. Appl.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2021.114685 (2021).

Abualigah, L. et al. Aquila optimizer: A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2021.107250 (2021).

Mohapatra, P., Das, K. N. & Roy, S. A modified competitive swarm optimizer for large scale optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 59, 340–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2017.05.060 (2017).

Sarangi, P. & Mohapatra, P. A novel cosine swarm algorithm for solving optimization problems. In Proc. of 7th International Conference on Harmony Search, Soft Computing and Applications: ICHSA 2022, 427–434, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2948-9_41 (2022).

Mohapatra, S. & Mohapatra, P. American zebra optimization algorithm for global optimization problems. Sci. Rep. 13, 5211. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-31876-2 (2023).

Sarangi, P. & Mohapatra, P. Evolved opposition-based mountain gazelle optimizer to solve optimization problems. J. King Saud Univ.-Comput. Inf. Sci.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101812 (2023).

Mohapatra, S., Sarangi, P. & Mohapatra, P. An improvised grey wolf optimiser for global optimisation problems. Int. J. Math. Oper. Res. 26, 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMOR.2023.134490 (2023).

Gopi, S. & Mohapatra, P. Opposition-based learning cooking algorithm (olca) for solving global optimization and engineering problems. Int. J. Mod. Phys. Chttps://doi.org/10.1142/S0129183124500517 (2023).

Mohapatra, S. & Mohapatra, P. An improved golden jackal optimization algorithm using opposition-based learning for global optimization and engineering problems. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 16, 147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44196-023-00320-8 (2023).

Kumar, N., Kumar, R., Mohapatra, P. & Kumar, R. Modified competitive swarm technique for solving the economic load dispatch problem. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 41, 173–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02522667.2020.1714184 (2020).

Huang, Z., Lin, Z., Zhu, Z. & Chen, J. An improved simulated annealing algorithm with excessive length penalty for fixed-outline floorplanning. IEEE Access 8, 50911–50920. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2980135 (2020).

Eskandar, H., Sadollah, A., Bahreininejad, A. & Hamdi, M. Water cycle algorithm-a novel metaheuristic optimization method for solving constrained engineering optimization problems. Comput. Struct. 110, 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2012.07.010 (2012).

Rashedi, E., Nezamabadi-Pour, H. & Saryazdi, S. Gsa: A gravitational search algorithm. Inf. Sci. 179, 2232–2248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2009.03.004 (2009).

Zhao, W., Wang, L. & Zhang, Z. Atom search optimization and its application to solve a hydrogeologic parameter estimation problem. Knowl.-Based Syst. 163, 283–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2018.08.030 (2019).

Mirjalili, S., Mirjalili, S. M. & Hatamlou, A. Multi-verse optimizer: A nature-inspired algorithm for global optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 27, 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-015-1870-7 (2016).

Abedinpourshotorban, H., Shamsuddin, S. M., Beheshti, Z. & Jawawi, D. N. Electromagnetic field optimization: A physics-inspired metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Swarm Evolut. Comput. 26, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2015.07.002 (2016).

Wei, Z., Huang, C., Wang, X., Han, T. & Li, Y. Nuclear reaction optimization: A novel and powerful physics-based algorithm for global optimization. IEEE Access 7, 66084–66109. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2918406 (2019).

Kashan, A. H. A new metaheuristic for optimization: Optics inspired optimization (oio). Comput. Oper. Res. 55, 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2014.10.011 (2015).

Faramarzi, A., Heidarinejad, M., Stephens, B. & Mirjalili, S. Equilibrium optimizer: A novel optimization algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 191, 105190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105190 (2020).

Hashim, F. A., Hussain, K., Houssein, E. H., Mabrouk, M. S. & Al-Atabany, W. Archimedes optimization algorithm: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Appl. Intell.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-020-01893-z (2021).

Pereira, J. L. J. et al. Lichtenberg algorithm: A novel hybrid physics-based meta-heuristic for global optimization. Expert Syst. Appl.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114522 (2021).

Lam, A. Y. & Li, V. O. Chemical-reaction-inspired metaheuristic for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 14, 381–399 (2009).

Islam, M. R., Saifullah, C. K. & Mahmud, M. R. Chemical reaction optimization: Survey on variants. Evolut. Intell. 12, 395–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12065-019-00246-1 (2019).

Alatas, B. Acroa: Artificial chemical reaction optimization algorithm for global optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 38, 13170–13180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2011.04.126 (2011).

Moghdani, R. & Salimifard, K. Volleyball premier league algorithm. Appl. Soft Comput. 64, 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2017.11.043 (2018).

Dehghani, M., Mardaneh, M., Guerrero, J. M., Malik, O. & Kumar, V. Football game based optimization: An application to solve energy commitment problem. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 13, 514–523. https://doi.org/10.22266/ijies2020.1031.45 (2020).

Dehghani, M., Trojovská, E. & Trojovskỳ, P. A new human-based metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems on the base of simulation of driving training process. Sci. Rep. 12, 9924. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14225-7 (2022).

Kaveh, A. & Kaveh, A. Tug of war optimization. Adv. Metaheur. Algorithms Opt. Des. Struct.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59392-6_15 (2021).

Rao, R. V., Savsani, V. J. & Vakharia, D. Teaching-learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput.-aided Des. 43, 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cad.2010.12.015 (2011).

Dehghani, M. et al. A new “doctor and patient’’ optimization algorithm: An application to energy commitment problem. Appl. Sci. 10, 5791. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10175791 (2020).

Moosavi, S. H. S. & Bardsiri, V. K. Poor and rich optimization algorithm: A new human-based and multi populations algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 86, 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2019.08.025 (2019).

Mousavirad, S. J. & Ebrahimpour-Komleh, H. Human mental search: A new population-based metaheuristic optimization algorithm. Appl. Intell. 47, 850–887. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10489-017-0903-6 (2017).

Glover, F. Tabu search-part I. ORSA J. Comput. 1, 190–206. https://doi.org/10.1287/ijoc.1.3.190 (1989).

Glover, F. Tabu search-part II. ORSA J. Comput. 2, 4–32. https://doi.org/10.1287/ijoc.2.1.4 (1990).

Atashpaz-Gargari, E. & Lucas, C. Imperialist competitive algorithm: an algorithm for optimization inspired by imperialistic competition. In 2007 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, 4661–4667, https://doi.org/10.1109/CEC.2007.4425083 (2007).

Kaveh, A. & Mahdavi, V. R. Colliding bodies optimization: A novel meta-heuristic method. Comput. Struct. 139, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2014.04.005 (2014).

Sadollah, A., Bahreininejad, A., Eskandar, H. & Hamdi, M. Mine blast algorithm: A new population based algorithm for solving constrained engineering optimization problems. Appl. Soft Comput. 13, 2592–2612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2012.11.026 (2013).

Dai, C., Zhu, Y. & Chen, W. Seeker optimization algorithm. In Computational Intelligence and Security: International Conference, CIS. Guangzhou, China, November 3–6, 2006. Revised Selected Papers, 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-74377-4_18 (2006).

Eita, M. & Fahmy, M. Group counseling optimization: A novel approach. In Research and Development in Intelligent Systems XXVI: Incorporating Applications and Innovations in Intelligent Systems XVII (eds Eita, M. & Fahmy, M.) 195–208 (Springer, 2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84882-983-1_14.

Eita, M. & Fahmy, M. Group counseling optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 22, 585–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2014.03.043 (2014).

Geem, Z. W., Kim, J. H. & Loganathan, G. V. A new heuristic optimization algorithm: Harmony search. Simulation 76, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/003754970107600201 (2001).

Kashan, A. H. League championship algorithm (LCA): An algorithm for global optimization inspired by sport championships. Appl. Soft Comput.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2013.12.005 (2014).

Al-Betar, M. A., Alyasseri, Z. A. A., Awadallah, M. A. & Abu Doush, I. Coronavirus herd immunity optimizer (chio). Neural Comput. Appl. 33, 5011–5042. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-020-05296-6 (2021).

Braik, M., Ryalat, M. H. & Al-Zoubi, H. A novel meta-heuristic algorithm for solving numerical optimization problems: Ali baba and the forty thieves. Neural Comput. Appl.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-06392-x (2022).

Sharma, S., Saha, A. K. & Lohar, G. Optimization of weight and cost of cantilever retaining wall by a hybrid metaheuristic algorithm. Eng. Comput.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-021-01294-x (2021).

Ang, K. M. et al. Modified teaching-learning-based optimization and applications in multi-response machining processes. Comput. Ind. Eng. 174, 108719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2022.108719 (2022).

Sharma, S., Saha, A. K., Majumder, A. & Nama, S. Mpboa-a novel hybrid butterfly optimization algorithm with symbiosis organisms search for global optimization and image segmentation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80, 12035–12076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-10053-x (2021).

Jiyue, E., Liu, J. & Wan, Z. A novel adaptive algorithm of particle swarm optimization based on the human social learning intelligence. Swarm Evolut. Comput. 80, 101336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2023.101336 (2023).

Bac, B. H. et al. Performance evaluation of nanotubular halloysites from weathered pegmatites in removing heavy metals from water through novel artificial intelligence-based models and human-based optimization algorithm. Chemosphere 282, 131012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131012 (2021).

Chakraborty, S., Sharma, S., Saha, A. K. & Saha, A. A novel improved whale optimization algorithm to solve numerical optimization and real-world applications. Artif. Intell. Rev.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-10114-z (2022).

Chakraborty, P., Sharma, S. & Saha, A. K. Convergence analysis of butterfly optimization algorithm. Soft Comput. 27, 7245–7257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00500-023-07920-8 (2023).

Sahoo, S. K., Sharma, S. & Saha, A. K. A novel variant of moth flame optimizer for higher dimensional optimization problems. J. Bionic Eng.https://doi.org/10.1007/s42235-023-00357-7 (2023).

Sharma, S., Khodadadi, N., Saha, A. K., Gharehchopogh, F. S. & Mirjalili, S. Non-dominated sorting advanced butterfly optimization algorithm for multi-objective problems. J. Bionic Eng. 20, 819–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42235-022-00288-9 (2023).

Sharma, S., Chakraborty, S., Saha, A. K., Nama, S. & Sahoo, S. K. mlboa: A modified butterfly optimization algorithm with Lagrange interpolation for global optimization. J. Bionic Eng. 19, 1161–1176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42235-022-00175-3 (2022).

Mirjalili, S. et al. Salp swarm algorithm: A bio-inspired optimizer for engineering design problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 114, 163–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2017.07.002 (2017).

Chopra, N. & Ansari, M. M. Golden jackal optimization: A novel nature-inspired optimizer for engineering applications. Expert Syst. Appl. 198, 116924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2022.116924 (2022).

Zhong, C., Li, G. & Meng, Z. Beluga whale optimization: A novel nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 251, 109215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2022.109215 (2022).

Heidari, A. A. et al. Harris hawks optimization: Algorithm and applications. Future Gen. Comput. Syst. 97, 849–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.future.2019.02.028 (2019).

Abdollahzadeh, B., Gharehchopogh, F. S., Khodadadi, N. & Mirjalili, S. Mountain gazelle optimizer: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic algorithm for global optimization problems. Adv. Eng. Softw. 174, 103282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2022.103282 (2022).

Seyyedabbasi, A. & Kiani, F. Sand cat swarm optimization: A nature-inspired algorithm to solve global optimization problems. Eng. Comput.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-022-01604-x (2022).

Faridmehr, I., Nehdi, M. L., Davoudkhani, I. F. & Poolad, A. Mountaineering team-based optimization: A novel human-based metaheuristic algorithm. Mathematics 11, 1273. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11051273 (2023).

Wolpert, D. H. & Macready, W. G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 1, 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.585893 (1997).

Zhao, W., Wang, L. & Mirjalili, S. Artificial hummingbird algorithm: A new bio-inspired optimizer with its engineering applications. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 388, 114194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cma.2021.114194 (2022).

Viktorin, A., Senkerik, R., Pluhacek, M., Kadavy, T. & Zamuda, A. Dish algorithm solving the CEC 2019 100-digit challenge. In 2019 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC) (eds Viktorin, A. et al.) 1–6 (IEEE, 2019).

Mohapatra, S. & Mohapatra, P. Fast random opposition-based learning golden jackal optimization algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2023.110679 (2023).

Wang, X., Li, C., Zhu, J. & Meng, Q. L-shade-e: Ensemble of two differential evolution algorithms originating from l-shade. Inf. Sci. 552, 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2020.11.055 (2021).

Hansen, N., Müller, S. D. & Koumoutsakos, P. Reducing the time complexity of the derandomized evolution strategy with covariance matrix adaptation (CMA-ES). Evolut. Comput. 11, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1162/106365603321828970 (2003).

Nadimi-Shahraki, M. H., Taghian, S. & Mirjalili, S. An improved grey wolf optimizer for solving engineering problems. Expert Syst. Appl. 166, 113917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.113917 (2021).

Gopi, S. & Mohapatra, P. A modified whale optimisation algorithm to solve global optimisation problems. In Proc. of 7th International Conference on Harmony Search, Soft Computing and Applications: ICHSA 2022, 465–477, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-2948-9_45 (2022).

Wilcoxon, F. Individual comparisons by ranking methods. In Breakthroughs in Statistics: Methodology and Distribution (ed. Wilcoxon, F.) 196–202 (Springer, 1992).

Friedman, M. The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 32, 675–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1937.10503522 (1937).

Hodges, J. L. Jr. & Lehmann, E. L. Rank methods for combination of independent experiments in analysis of variance. In Selected Works of EL Lehmann (eds Hodges, J. L., Jr. & Lehmann, E. L.) 403–418 (Springer, 2011).

Arora, J. S. Introduction to Optimum Design (Elsevier, 2004).

Coello, C. A. C. Use of a self-adaptive penalty approach for engineering optimization problems. Comput. Ind. 41, 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-3615(99)00046-9 (2000).

Sattar, D. & Salim, R. A smart metaheuristic algorithm for solving engineering problems. Eng. Comput. 37, 2389–2417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-020-00951-x (2021).

Sandgren, E. Nonlinear integer and discrete programming in mechanical design. Int. Des. Eng. Tech. Conf. Comput. Inf. Eng. Conf. 26584, 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC1988-0012 (1988).

Chickermane, H. & Gea, H. C. Structural optimization using a new local approximation method. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 39, 829–846. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0207(19960315)39:5/3C829::AID-NME884/3E3.0.CO;2-U (1996).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gopi S: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing-original draft. Prabhujit Mohapatra: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gopi, S., Mohapatra, P. Learning cooking algorithm for solving global optimization problems. Sci Rep 14, 13359 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60821-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60821-0

This article is cited by

-

Parameter extraction of PV models under varying meteorological conditions using a modified electric eel foraging optimization algorithm

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Parameter estimation of PEM fuel cell by using Enhanced Arctic Puffin Optimization algorithm

Ionics (2025)

-

Metaheuristic Algorithms Since 2020: Development, Taxonomy, Analysis, and Applications

Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering (2025)

-

A novel Q-learning-inspired Mountain Gazelle Optimizer for solving global optimization problems

International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics (2025)