Abstract

Spared regions of the damaged central nervous system undergo dynamic remodelling and exhibit a remarkable potential for therapeutic exploitation1. Lesion-remote astrocytes (LRAs), which interact with viable neurons and glia, undergo reactive transformations whose molecular and functional properties are poorly understood2. Here, using multiple transcriptional profiling methods, we investigated LRAs from spared regions of mouse spinal cord following traumatic spinal cord injury. We show that LRAs acquire a spectrum of molecularly distinct, neuroanatomically restricted reactivity states that evolve after spinal cord injury. We identify transcriptionally unique reactive LRAs in degenerating white matter that direct the specification and function of local microglia that clear lipid-rich myelin debris to promote tissue repair. Fuelling this LRA functional adaptation is the secreted matricellular protein CCN1. Loss of astrocyte-derived CCN1 results in excessive, aberrant activation of local microglia, characterized by abnormal molecular specification, impaired debris processing reflected by the intracellular accumulation of myelin and axon debris, and dysregulated lipid metabolism with distinctive attenuation in lipid droplet accumulation. Mechanistically, we find that CCN1 binds microglial SDC4 to augment lipid storage, linking this signalling axis to a vital repair-associated lipid buffering response in debris-clearing microglia. Accordingly, microglial deficits resulting from astrocyte CCN1 depletion culminate in blunted clearance of white matter debris and impaired neurological recovery from spinal cord injury. Ccn1-expressing white matter astrocytes are induced by local myelin damage and are generated in diverse demyelinating disorders in mice and humans, pointing to their fundamental, evolutionarily conserved role in white matter repair. Our findings show that context-specific cues shape regionally distinct LRA reactivity states with functional adaptations that orchestrate multicellular processes underlying neural repair and influence disease outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Astrocytes tile the central nervous system (CNS), where they serve vital roles that uphold healthy nervous system function, including regulation of synapse development, buffering of neurotransmitters and ions, and provision of metabolic substrates3. In response to diverse CNS insults, astrocytes exhibit context-specific transformations that are collectively referred to as reactivity4,5,6,7,8,9. The characteristics of regionally and molecularly distinct reactivity states are incompletely understood. The mechanisms through which different reactivity states arise, how they evolve or resolve over time, and their consequences for local cell function and CNS disorder progression remain unknown.

Immediately adjacent to CNS lesions, border-forming astrocytes (BFAs) undergo transcriptional reprogramming and proliferation to form a neuroprotective barrier that restricts inflammation and supports axon regeneration10,11. Beyond the lesion, spared but dynamic regions of the injured CNS exhibit varying degrees of synaptic circuit remodelling and progressive cellular responses to secondary damage that have profound consequences for neural repair and recovery2,12. Throughout these cytoarchitecturally intact, but injury-reactive regions, LRAs intermingle with neurons and glia, undergo little to no proliferation, and exhibit varying degrees of cellular hypertrophy13,14. The molecular and functional properties of LRAs remain undefined, and whether regionally restricted microenvironments impose discrete astrocyte reactivity states is not understood. Therapeutically harnessing spared regions of the injured CNS will require a clearer understanding of the accompanying cellular and molecular landscape.

Here, we leveraged integrative transcriptional profiling methodologies to identify multiple spatiotemporally resolved, molecularly distinct states of LRA reactivity within the injured spinal cord. We show that LRAs exhibit a transcriptional identity that is distinct from that of BFAs and astrocytes associated with non-traumatic spinal cord insults and disorders. We used computational modelling of LRA-mediated heterotypic cell interactions, astrocyte-specific gene deletion, and multiple mouse models of acute and chronic CNS white matter degeneration to reveal and probe a previously unrecognized white matter LRA reactivity state. We show that this state (1) is induced by local myelin damage; (2) serves to govern the molecular, metabolic and functional specification of debris-clearing microglia; and (3) supports neurological recovery after injury. Our findings further suggest that CCN1 secreted by white matter LRAs may bind SDC4 on microglia to augment their lipid storage activity. Astrocyte-specific CCN1 depletion attenuates white matter debris clearance and impairs neurological recovery after spinal cord injury (SCI), linking LRA-mediated CCN1 signalling to vital repair-associated lipid buffering responses in debris-clearing microglia. These findings position LRAs as key orchestrators of multicellular neural repair processes that promote functional recovery after CNS injury.

Molecular dissection of LRAs after SCI

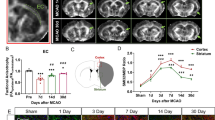

LRAs exhibit varying degrees of hypertrophy and intermingle with viable neurons, glia and neural circuitry throughout cytoarchitecturally intact regions of the injured CNS13 (Fig. 1a). Whether LRA reactivity evolves or resolves over time and how this form of reactivity differs from BFAs is unclear. We addressed these questions first by broadly examining injury-reactive gene expression dynamics of LRAs in a mouse model of anatomically and functionally incomplete SCI (iSCI). After iSCI, spared regions of the injured spinal cord rostral and caudal to the lesion undergo synaptic circuit reorganization that re-establishes brain–cord communication and gives rise to recovery of locomotor behaviour1,12,15 (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Concurrently, discrete spared white matter regions undergo widespread Wallerian axon degeneration, which gives rise to chronic gliosis and inflammation16. We performed bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of astrocyte-specific ribosome-associated mRNA (RiboTag) and whole-tissue mRNA from spared tissue regions rostral and caudal to the lesion epicentre at multiple post-injury time points. These time points reflect distinct phases of functionally meaningful neuroplasticity and locomotor recovery after iSCI1 (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Thus, we could investigate LRA transcriptional dynamics associated with post-traumatic neuroplasticity, inflammation and neurological recovery.

a, Comparison of BFAs and hypertrophic reactive LRAs after iSCI. b, RNA-seq of LRAs. HA, haemagglutinin. c, DEGS in bulk RNA-seq of LRAs (false discovery rate (FDR) P ≤ 0.05) at 3 (n = 5), 7 (n = 4), 14 (n = 6), and 28 (n = 6) dpi versus healthy LRAs (n = 5). Rostral and caudal data are combined. d, BFA expression of LRA DEGs across acute (3 dpi), subacute (7 and 14 dpi), and chronic (28 dpi) post-injury phases. On average, 46% of LRA DEGs are either not regulated in BFAs or are regulated in the opposite direction across these phases. e, Principal component analysis of astrocyte DEGs from SCI LRAs and BFAs, EAE, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-reactive spinal cord astrocytes relative to healthy spinal cord astrocytes. LRAs acquire a separable reactivity state with a distinct trajectory relative to SCI and non-traumatic CNS insults. f, Schematic of combined snRNA-seq and spatial transcriptomics approach for investigating SCI-reactive LRAs and neighbouring cell types. g, Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) of cell types identified by snRNA-seq in healthy and all post-injury (all time points) spinal cord (230,570 cells). Tissue collected from uninjured thoracic (n = 5), uninjured lumbar (n = 4), 3 dpi thoracic (n = 4), 3 dpi lumbar (n = 4), 7 dpi thoracic (n = 4), 7 dpi lumbar (n = 4), 28 dpi thoracic (n = 6) and 28 dpi lumbar (n = 3) spinal cords. h, Diagram of intraspinal regions used in deconvolution of spatial transcriptomic data (n = 4 mice per time point per region). GM, grey matter; WM, white matter. i, UMAP of healthy and iSCI astrocytes, illustrating neuroanatomically restricted LRA subtypes and their distinct molecular states. Ast, astrocytes; cGM, central grey matter; dGM, dorsal grey matter; vGM, ventral grey matter. j, Spatial transcriptomic characterization of vGM3 astrocytes illustrates restricted positioning in ventral horn grey matter. k, High-magnification image of vGM3 markers Arex and Thrsp in Gfap+/Aldoc+ ventral horn grey matter astrocytes. Scale bars, 10 µm. l, Spatial transcriptomic characterization of WM4 astrocytes illustrates unilaterally restricted white matter expression. m, High-magnification image of WM4 markers shows expression of Glipr2 and Ccn1 in Gfap+/Aldoc+ white matter astrocytes. Scale bars, 10 µm. n, Heat map showing relative expression of functionally related genes across regionally restricted LRA molecular states. ECM, extracellular matrix; MHC, major histocompatibility complex. Exact P values are provided in the Source Data.

Analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) uncovered large and persistent alterations in astrocyte molecular profile that progress over time following injury, many of which were significantly astrocyte enriched (Fig. 1c, Extended Data Fig. 1b–d and Supplementary Data 1). LRA DEG profiles were largely distinct from BFAs17, with an average of 46% (range: 34.4–52.2%) of LRA DEGs being either not regulated in BFA or altered in the opposite direction across acute, subacute and chronic time periods post-injury (Fig. 1d). Temporal transcriptomic profiles of LRAs and BFAs occupied discrete domains in principal component space (Fig. 1e). Further, we compared LRAs to reactive spinal cord astrocyte subtypes from across multiple divergent, non-traumatic CNS insults. DEG profiles of astrocytes from each of these conditions were heterogenous and exhibited divergent positioning in principal component space relative to LRAs (Fig. 1e and Extended Data Fig. 1b). Thus, LRAs undergo a reactive transformation in molecular phenotype that is unique relative to BFAs of the injured spinal cord and constitutes a subtype of reactivity that is distinct from that observed in spinal cord astrocytes under the context of divergent non-traumatic neurological disorders. Analysis of DEGs in LRAs revealed divergent patterns of temporal regulation and distinct functional pathway enrichment (Extended Data Fig. 1e–g). We also found that genetic deletion of astrocyte Stat3 (Stat3-cKO), a reactivity master regulator9, markedly attenuates injury-reactive LRA gene expression (Extended Data Fig. 1h and Supplementary Data 2). However, the effects of Stat3-cKO on LRA reactivity due to altered BFA function cannot be ruled out.

Together, these findings show that LRAs in spared regions of the injured spinal cord undergo a profound degree of transcriptional reprogramming that evolves over time after iSCI. The majority of injury-reactive alterations in LRA gene expression are: (1) divergent from SCI BFAs; (2) prominently distinct from other reactive subtypes observed in the spinal cord under diverse neurological insults and disorders; and (3) may be dependent on phosphorylation-dependent STAT3 signalling.

LRAs exhibit spatiotemporal heterogeneity

In contrast to BFAs, LRAs tile anatomically and functionally discrete white and grey matter domains of grossly intact spinal cord regions13. We reasoned that since transcriptional profiles of reactive astrocytes are highly context-dependent, LRAs from different neuroanatomical microenvironments of the injured cord may manifest divergent reactivity states. To test this hypothesis, we performed single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics on equivalent spared regions of the injured adult mouse spinal cord rostral and caudal to an iSCI lesion at 3, 7 and 28 days post injury (dpi) (Fig. 1f–h and Extended Data Fig. 2).

We identified 12 distinct astrocyte molecular states, the relative proportions of which varied from healthy to injured, and across post-injury time points (Fig. 1i). snRNA-seq profiles were used to deconvolve spatial transcriptomic data and map astrocyte molecular states to their native intraspinal anatomical location (Fig. 1h,i). This approach revealed that distinct snRNA-seq astrocyte subtypes mapped to discrete anatomical regions within the white matter and grey matter of the healthy and injured spinal cord (Fig. 1i–m and Extended Data Fig. 3a–i). Multiple grey matter astrocyte subtypes with unique spatiomolecular profiles along the dorsoventral axis of the spinal cord were also defined (Fig. 1i–k and Extended Data Fig. 3a–h). This separation of spinal cord astrocytes in functional neuroanatomical space paralleled marked transcriptional divergence, suggesting that region-specific alterations in LRA molecular state may differentially influence local cellular function, with consequences for neural tissue remodelling, inflammation and repair (Fig. 1n and Supplementary Data 3).

Decoding LRA reactivity states after SCI

We found multiple hypertrophic LRA reactivity states with characteristically increased expression of intermediate filament genes (Gfap and Vim) and that exhibit unique spatiotemporal profiles (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 3j). LRAs in the sensory laminae of the dorsal horn grey matter (dGM1 and dGM2) demonstrated a notable shift in molecular profile from dGM1 towards a dGM2 molecular state at 28 dpi (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 3c–g). Relative to astrocytes in the healthy dorsal horn grey matter (dGM1), the chronic dGM2 LRA reactivity state is characterized by increased expression of Glt1, Grm5 and multiple ionotropic AMPA glutamate receptor genes (Gria4, Grid1 and Grid2). dGM2 astrocytes also upregulate synaptogenic glypicans (Gpc5 and Gpc6) and genes implicated in debris and synapse phagocytosis (Megf10, Mertk and Dock1) (Fig. 1n and Supplementary Data 3). LRAs from the ventral grey matter (vGM1, vGM2 and vGM3) displayed a robust, but transient shift from vGM1 to vGM2 and vGM3 molecular state representation during acute and subacute post-injury time points (Fig. 1i–k and Extended Data Fig. 3a,h). Relative to astrocytes in the healthy ventral grey matter (vGM1), vGM2 and vGM3 LRAs dynamically upregulate metabotropic glutamate receptors Grm3 and Grm5. C1qa, C1qb, C1qc and C4b were also upregulated, consistent with potential involvement in complement-mediated post-traumatic synaptic circuit remodelling. Intra-regional reactive LRA heterogeneity is underscored by vGM2 versus vGM3 transcriptional differences. For example, LRAs acquiring a vGM2 reactivity state downregulate GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) transporters (Gat1 and Gat3) and the primary astrocyte inward rectifying K+ channel Kir4.1 (Kcnj10), by contrast, vGM3 LRAs upregulate expression of these genes. vGM3 astrocytes also exhibited distinctly higher expression of genes encoding GABA receptor subunits (Gabbr1, Gabbr2 and Gabrg1), glutamate uptake and metabolism genes (Slc1a2, Slc1a3, Glul and Glud1) and key sterol metabolism genes (Hmgcs1, Dhcr24 and Sqle) (Fig. 1n and Supplementary Data 3). Thus, grey matter LRAs acquire region-specific hypertrophic reactivity states (dGM2, vGM2 and vGM3) with potential circuit-specific and functional consequences.

Hypertrophic white matter LRAs exhibiting WM2, WM3 or WM4 molecular states are restricted to the injured spinal cord and exhibit a lesion ipsilateral regional identity (Fig. 1i,l,m and Extended Data Figs. 2e and 3a,b,i). White matter LRA transcriptomic profiles evolve over time, with a greater proportion WM2 and WM3 LRAs at acute and subacute time points, transitioning to a WM4 molecular state in the chronic post-injury phase (Fig.1i). Relative to healthy white matter astrocytes (WM1), WM2, WM3 and WM4 LRAs displayed indicators of metabolic plasticity, namely widespread upregulation of lactate metabolism and transport genes (such as Mct1, Mct2 and Ldha) and glycolysis genes (such as Pgam1, Pgk1 and Pkm), which may underlie astrocyte-mediated alterations in axonal energy metabolism in lesion-remote white matter (Fig. 1n and Supplementary Data 3). Of note, we determined that WM2, WM3 and WM4 LRAs showed persistently increased expression of immune and inflammamodulatory genes, potentially implicating them in chronic white matter inflammation and repair (for example, Lcn2, Cxcl12, Ptx3, Tgfb1 and Tgfb2).

White matter degeneration-associated microglia

Deconvolution of our spatial transcriptomics data was used to define co-occurring cell states across space and time (Fig. 2a). This analysis identified multiple region-specific grey matter LRAs and co-occurring neurons, glia and endothelia (Extended Data Fig. 4). We further determined an ipsilesional white matter niche comprised of reactive white matter LRAs (WM3 and WM4 (hereafter WM3/4)) and two co-occurring white matter-restricted microglia subtypes (Mg2 and Mg5 (Mg2/5) with largely overlapping transcriptomic identities (Fig. 2b–d and Extended Data Fig. 5).

a, Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) on deconvolved spatial transcriptomics data was used to identify co-occurring cell states across space and time. NMF loading weights plotted across healthy and post-injury time points predicts injury-reactive alterations in regionally co-occurring cell states. b, Spatial plotting of NMF 4 reveals enrichment in lesion ipsilateral white matter. NMF 4 is primarily composed of white matter LRAs (WM3/4) and Mg2/Mg5 microglia. c, Spatial transcriptomic localization of Mg2/Mg5 microglia and WM3/4 astrocytes illustrate overlapping unilateral white matter enrichment. d, Volcano plot of DEGs in Mg2/5 microglia versus homeostatic microglia (Mg1 and Mg3 (Mg1/3) (FDR P ≤ 0.05). FC, fold change. e,f, Dot plot of mean normalized expression of metabolism and function (e) and previously published microglia state-associated molecular signatures18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 (f) in iSCI lesion-remote microglia clusters. g, WDM assemble into multicellular nodules that phagocytose myelin debris. Scale bars, 10 µm. h, NicheNet analysis of reactive WM3/4 LRAs (senders) and WDM (Mg2/5) (receivers) identified several putative ligands secreted by white matter astrocytes. i, Ccn1 is selectively expressed by LRAs neighbouring WDM nodules in degenerating white matter. Scale bar, 10 µm. j, Left, aligned average density plots of Ccn1-expressing astrocytes, illustrating regional and intraspinal relationships between Ccn1+ LRAs and anatomically defined zones of Wallerian degeneration. Right, quantification of Ccn1+ astrocytes per time point in each region. Cells were counted from cervical healthy (n = 5), thoracic healthy (n = 6), lumbar healthy (n = 4), cervical 3 dpi (n = 3), thoracic 3 dpi (n = 5), lumbar 3 dpi (n = 4), cervical 7 dpi (n = 5), thoracic 7 dpi (n = 4), lumbar 7 dpi (n = 5), cervical 14 dpi (n = 4), thoracic 14 dpi (n = 4), lumbar 14 dpi (n = 4), cervical 28 dpi (n = 4), thoracic 28 dpi (n = 8), lumbar 28 dpi (n = 6), cervical 90 dpi (n = 4), thoracic 90 dpi (n = 5) and lumbar 90 dpi (n = 4); 2–11 sections per mouse, region or time point. Scale bars, 250 µm. k, Schematic of iSCI lesion-remote spinal cord regions and expected patterns of Wallerian degeneration from which Ccn1+ astrocytes were evaluated. l, WDM nodules in Wallerian degenerating dorsal white matter (mid-thoracic) from wild-type (WT) and Ccn1-cKO spinal cord following iSCI. Yellow arrowheads indicate WDM in Wallerian degenerating regions; white arrowheads indicate spatially aberrant WDM nodules. Scale bars, 250 µm. m, Left, aligned average density plots of WDM nodules in Ccn1-cKO spinal cord after iSCI. Right, quantification of WDM nodules from lumbar, thoracic and cervical spinal cord of wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice following iSCI. Statistical comparison between wild-type and Ccn1-cKO nodule counts by Conway–Maxwell–Poisson method and Tukey’s post hoc test. Nodules were counted from WT cervical 7 dpi (n = 5), Ccn1-cKO cervical 7 dpi (n = 5), WT thoracic 7 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO thoracic 7 dpi (n = 4), WT lumbar 7 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO lumbar 7 dpi (n = 4), WT cervical 28 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO cervical 28 dpi (n = 4), WT thoracic 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO thoracic 28 dpi (n = 5), WT lumbar 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO lumbar 28 dpi (n = 4), WT cervical 90 dpi (n = 5), Ccn1-cKO cervical 90 dpi (n = 4), WT thoracic 90 dpi (n = 5), Ccn1-cKO thoracic 90 dpi (n = 5), WT lumbar 90 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO lumbar 90 dpi (n = 5), 2–11 sections per mouse, genotype region or time point. Graphs show mean ± s.e.m. In graphs of histological counts or continuous data, coloured data points represent the mean value for each biological replicate (individual mouse); grey data points indicate replicate measurements from individual tissue sections. Unless stated otherwise, statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA on mean values from biological replicates with Holm–Sidak’s post hoc test. Scale bars, 250 µm. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.002, ***P ≤ 0.0002, ****P ≤ 0.0001; NS, not significant. Exact P values are provided in the Source Data.

Relative to homeostatic microglia (Mg1 and Mg3) and Mg2/5 microglia showed coordinated upregulation of genes involved in phagocytosis, lipid metabolism and inflammatory regulation, accompanied by suppression of homeostatic genes (Fig. 2d,e and Extended Data Fig. 5d–f). Their molecular profile resembled that of phagocytic microglia that emerge in ageing, injury or in developmental white matter, including white matter-associated (WAM) and disease-associated (DAM) states18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 (Fig. 2f). These data define Mg2/5 microglia as a conserved white matter inflammation- and repair-associated state across diverse CNS disorders. Remarkably, we that find molecular markers of the Mg2/5 snRNA-seq profile correspond to microglia within Wallerian degenerating white matter that gradually assemble into multicellular nodules and phagocytose myelin debris (Fig. 2d,g and Extended Data Fig. 5g). We refer to these cells collectively as white matter degeneration-associated microglia (WDM).

WDM intermingle with Ccn1+ LRAs

Although some fundamental properties of debris-clearing microglia are characterized in white matter damage and disease20,25,27,28,29, the cellular interactions that shape microglia responses, and how these affect debris clearance efficacy, inflammation regulation, repair or recovery after CNS injury are not well defined. We carried out NicheNet analysis30 to identify ligand-mediated pathways of communication from reactive WM3/4 LRAs and Mg2/5 WDM (Fig. 2h). Expression validation of putative WM3/4 LRA-derived ligands determined that cellular communication network factor 1 (Ccn1), which encodes a secreted matricellular protein, is prominently and specifically expressed by LRAs within degenerating spinal cord white matter (Fig. 2h–k). Ccn1-expressing LRAs intimately associate with myelin debris-clearing WDM nodules (Fig. 2i and Extended Data Fig. 6a). In the healthy spinal cord, Ccn1 expression is mainly restricted to ependymal cells, with astrocyte expression being exceptionally rare (Fig. 2j and Extended Data Fig. 6b–d). As early as 3 days post-SCI, abundant Ccn1-expressing astrocytes are found throughout degenerating white matter and persist for at least 90 dpi (Fig. 2j and Extended Data Fig. 6d,e). Notably, Ccn1+ LRAs contained significantly increased nuclear levels of YAP1, a canonical activator of Ccn1 transcription (Extended Data Fig. 6f). Consistently, we found that CCN1 is actively secreted by adult mouse astrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 6g and Supplementary Fig. 1). In contrast to LRAs, the number of Ccn1-expressing ependymal cells was unaltered by SCI (Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). Correspondingly, increased levels of CCN1 protein were detected in spared regions of the injured spinal cord, which can be attributed to Ccn1+ white matter LRAs (Fig. 2j, Extended Data Fig. 6b–d,h and Supplementary Fig. 1). A spinal cord-wide, spatiotemporally resolved analysis of Ccn1-expressing astrocytes revealed an unequivocal intraspinal regional relationship between Ccn1+ astrocytes and anatomically defined zones of Wallerian axon degeneration (Fig. 2j,k and Extended Data Fig. 6i,j).

Together, these data demonstrate that after SCI, a subset of reactive white matter LRAs (1) rapidly and persistently upregulate CCN1; (2) are restricted to Wallerian degenerating white matter; and (3) neighbour debris-clearing WDM nodules.

Astrocyte CCN1 restricts white matter inflammation

To determine the function of astrocyte-secreted CCN1, we examined WDM specification and function throughout lesion-remote Wallerian degenerating white matter after iSCI in young adult wild-type mice, and mice with conditional astrocyte-specific31 Ccn1 gene deletion32 (Ccn1-cKO mice, Aldh1l1-CreERT2::Ccn1fl/fl) (Extended Data Fig. 7a–f). Given the sustained intimate spatial relationship between Ccn1+ astrocytes and WDM (Fig. 2i), we quantified nodule formation dynamics across the rostrocaudal axis of the injured spinal cord (Fig. 2l,m and Extended Data Fig. 7g–k). WDM nodule accumulation was markedly accelerated in Ccn1-cKO mice, with significantly increased nodule formation evident by 7 dpi (Fig. 2l,m and Extended Data Fig. 7i). This amplified microglial response was observed across all spinal cord regions examined and persisted to 90 dpi, reaching up to a fourfold increase in WDM nodules relative to wild type (Fig. 2l,m and Extended Data Fig. 7i). Lesion-remote regions of the spinal cord of Ccn1-cKO mice also exhibited ectopic inflammation, including the increased presence of WDM nodules in the rostral corticospinal tract, contralateral white matter and grey matter (Fig. 2l,m and Extended Data Fig. 7i–k). Therefore, loss of astrocyte-derived CCN1 results in accelerated, chronically excessive and spatially aberrant activation of phagocytic microglia in degenerating white matter.

Astrocyte CCN1 aids white matter repair

We investigated whether loss of astrocyte CCN1 signalling affects WDM-mediated phagocytosis of lipid-rich myelin and axon debris (Fig. 3a–i and Extended Data Fig. 7l). By 90 dpi, Ccn1-cKO microglia contained an approximately 40% greater volume of internalized myelin debris, and around 23% greater volume of axon debris than their wild-type equivalents (Fig. 3b–e and Extended Data Fig. 7l). Loss of astrocyte-secreted CCN1 resulted in a higher overall proportion of microglia containing myelin or axon debris at 90 dpi (Fig. 3f,g). However, we observed that loss of astrocyte CCN1 also led to significantly attenuated debris clearance (Fig. 3a,h,i). Thus, although loss of astrocyte CCN1 signalling results in the amplified accumulation of phagocytic microglia, these cells become engorged with undigested debris and do not mount an efficient debris clearance programme—a process that is critical for white matter repair.

a, Low-magnification image showing FluoroMyelin-labelled myelin debris and IBA1+ WDM nodules in Wallerian degenerating dorsal white matter of iSCI lesion-remote spinal cord (mid-thoracic) of wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. b, High-magnification 3D reconstructions showing IBA1+ WDM nodules with internalized FluoroMyelin-labelled myelin. Scale bars, 10 μm. c, Quantification of internalized myelin in WDM from uninjured control (healthy) and iSCI wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice. WT healthy (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 2), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6). FM, FluoroMyelin. d, High-magnification 3D reconstructions showing IBA1+ WDM nodules with internalized axon debris labelled with the neurofilament monoclonal antibody SMI32. Scale bars, 10 μm. e, Quantification of internalized axon debris in WDM from WT healthy (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6) mice. f, Proportion of WDM containing internalized myelin debris in WT healthy (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6) mice. g, Proportion of WDM containing internalized axon debris. WT healthy (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6). h, Quantification of extracellular myelin debris accumulation in Wallerian degenerating dorsal white matter from WT healthy (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6) mice. i, Quantification of extracellular axon debris accumulation in Wallerian degenerating dorsal white matter from WT healthy (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6) mice. j, Quantification of cold thermoception behaviour recovery in left (lesion ipsilesional) hindpaw after iSCI (n = 8 WT mice, n = 7 Ccn1-cKO mice). k, Quantification of mechanosensation behaviour recovery in left (lesion ipsilesional) hindpaw after iSCI as assessed by Von Frey testing (n = 8 wild-type mice, n = 7 Ccn1-cKO mice). Graphs show mean ± s.e.m. In graphs of histological continuous data, coloured data points represent the mean value for each biological replicate (individual mouse); grey data points indicate replicate measurements from individual tissue sections. Unless stated otherwise, statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA on mean values from biological replicates with Holm–Sidak post hoc test. Exact P values are provided in the Source Data.

Impaired clearance of myelin debris can restrict white matter repair33. We examined whether deficient astrocyte Ccn1 expression also affects spontaneous recovery of sensorimotor function after iSCI. Remarkably, recovery of locomotor function after iSCI was equivalent across wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice (Extended Data Fig. 7m). iSCI severs the spinothalamic tract, which transmits information about pain, temperature and mechanosensation. We evaluated spinothalamic function after iSCI by measuring hindpaw sensitivity to non-noxious cold stimuli. In contrast to wild-type iSCI mice, who exhibited a full recovery of cold sensitivity, Ccn1-cKO iSCI mice did not recover cold thermoception (Fig. 3j and Extended Data Fig. 7n). Spinothalamic tract function was further assessed by Von Frey assay, which revealed a divergence in the trajectory of mechanosensory recovery, with Ccn1-cKO mice, but not wild-type mice, returning to baseline sensitivity by 84 dpi (Fig. 3k and Extended Data Fig. 7o). Therefore, astrocyte-secreted CCN1 regulates neurological recovery after SCI.

CCN1 reprogrammes microglial lipid metabolism

Next, we sought to dissect the direct effects of CCN1 on microglia by investigating molecular mechanisms underlying their apparent dysfunction in metabolizing phagocytosed debris from the degenerating Ccn1-cKO white matter. Transcriptomic analysis of CCN1-stimulated naïve microglia revealed the prominent upregulation of TREM2-dependent WAM25 and stage 2 DAM26 gene signatures previously linked to white matter repair, debris clearance and neuroprotection, which include genes related to phagocytosis and lipid metabolism (Cst7, Cd63, Clec7a, Lpl, Lgals3, Spp1 and Tspo), (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Data 4). In microglia, TREM2 signalling mediates the alterations in molecular profile that are necessary for metabolizing lipid-rich myelin debris25,27. TREM2 levels in WDM were markedly attenuated in the absence of astrocyte CCN1, which could curb their molecular and functional specification (Fig. 4c,d and Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). Indeed, microglia nodules from the injured Ccn1-cKO spinal cord white matter exhibit aberrant expression of Gpnmb and Igf1, which are central molecular indicators of the WDM transcriptional signature (Fig. 4e–h and Extended Data Fig. 8c,d). CCN1 also mediated broad enhancement of lipid uptake and expression of lipid storage genes (Plin3, Acat1, Pparg, Fabp4, Fabp5, Olr1 and Marco), while suppressing the expression of genes required for lipid efflux (Abca1, Abca3, Abca5, Abca7 and Apoe) (Fig. 4a,b and Supplementary Data 4). Congruently, treatment of wild-type microglia with recombinant CCN1 significantly reduced cholesterol efflux (Fig. 4i and Extended Data Fig. 8e). Thus, CCN1 signals directly to microglia to instruct transcriptomic alterations for lipid metabolism reprogramming implicated in lipid uptake, intracellular processing of lipid-rich cellular debris, and associated buffering of excess lipids.

a,b, Volcano plot of all DEGs (a) and associated functional pathway modulation (b) in CCN1-stimulated primary microglia, as determined by RNA-seq (log2-transformed fold change versus vehicle (BSA), FDR P ≤ 0.05; vehicle, n = 3, and CCN1, n = 4). c,d, High-magnification 3D reconstruction (c) and quantification (d) of TREM2 in wild-type and Ccn1-cKO WDM. WT healthy (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 6), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6), Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6). e,f, High-magnification 3D reconstruction (e) and quantification (f) of Gpnmb expression in WDM, data from WT healthy (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 28 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 4), WT 90 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 4). g,h, High-magnification 3D reconstruction (g) and quantification (h) of Igf1 expression in WDM from WT healthy (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 4), WT 90 dpi (n = 3) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 4) mice. i, Cholesterol efflux from cultured primary mouse microglia (n = 5 replicates from independent cultures run in triplicate; Students t-test, **P ≤ 0.002). j, schematic for SCI lesion-remote microglia lipidomics. MRM, multiple reaction monitoring. k, Principal component analysis of lipidomic profiles of healthy and iSCI microglia from wild-type and Ccn1-cKO spinal cord. Microglia were isolated from WT healthy (n = 5), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 6), WT 28 dpi (n = 6) and Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 5) mice. l, Comparison of wild-type and Ccn1-cKO injury-reactive alterations in microglia lipid profile (log2-transformed fold change, iSCI versus healthy, FDR P ≤ 0.05). White represents non-significantly altered lipid species. CAR, carnitines; CE, cholesterol esters; CER, ceramides; FA, fatty acids; PC, phosphatidylcholines; PE, phosphatidylethanolamines; PG, phosphatidylglycerols; PI, phosphatidylinositols; PS, phosphatidylserines; SM, sphingomyelins; TAG, triacylglycerols. m,n, High-magnification 3D reconstructions (m) and quantification (n) of BODIPY+ lipid droplets in WDM from WT healthy (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 7 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO 7 dpi (n = 4), WT 28 dpi (n = 6), WT Ccn1-cKO (n = 5), WT 90 dpi (n = 6) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 6) mice. o,p, High-magnification 3D reconstructions (o) and quantification (p) of Abca1 expression in WDM from WT healthy (n = 3), Ccn1-cKO healthy (n = 3), WT 28 dpi (n = 4), Ccn1-cKO 28 dpi (n = 4), WT 90 dpi (n = 4) and Ccn1-cKO 90 dpi (n = 4) mice. q, Left, schematic for CCN1 receptor identification assay. Right, volcano plot of CCN1 binding partners in microglia from proteomic analysis of CCN1-directed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) (n = 4 experimental replicates from independent cultures; log2-transformed fold change ≥2, CCN1 co-immunoprecipitation versus negative control antibody co-immunoprecipitation; t-test −log10P > 1.3). Labels indicate microglial candidate CCN1 receptors. r,s, High-magnification images (r) and quantification (s) of Sdc4 in healthy IBA1+ microglia and IBA1+/Gpnmb+ WDM nodules from Wallerian degenerating regions in wild-type mice (n = 5 mice per group; two-sided Student’s t-test, *P ≤ 0.05). t,u, Quantification of lipid storage in microglia by flow cytometric analysis of lipid droplet-associated neutral lipid content in microglia with CCN1 and antibody treatments. Ctrl Ab, isotype control antibodies; fbAb, function-blocking antibodies. t, Median intensity of neutral lipid staining. u, Representative distribution of cell counts and intensity of neutral lipid staining (n = 4 replicates from independent cultures; one-way ANOVA with Holm–Sidak post hoc test, ****P ≤ 0.0001). AU, arbitrary units. Unless stated otherwise, graphs show mean ± s.e.m. In graphs of histological counts or continuous data, coloured data points represent the mean value for each biological replicate (individual mouse); grey data points indicate replicate measurements from individual tissue sections. Unless stated otherwise, statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA on mean values from biological replicates with Holm–Sidak post hoc test. Exact P values are provided in the Source Data. Scale bars, 10 μm.

CCN1 directs microglial lipid buffering

CCN1 directly modulates microglial lipid metabolism gene expression and loss of astrocyte CCN1 leads to amplified activation of debris-laden microglia nodules, but impairs debris clearance. Intracellular accumulation of myelin debris-derived lipids and impaired debris clearance have been linked to maladaptive shifts in microglial lipid metabolism, including disruptions in essential lipid buffering mechanisms (lipid efflux and storage) that are required for white matter repair20,25,27,33,34. Therefore, we determined whether astrocyte-secreted CCN1 regulates microglia lipid metabolism in vivo by performing an unbiased lipidomics analysis on whole-cell extracts of microglia from lesion-remote spinal cord regions undergoing Wallerian degeneration in wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice (Fig. 4j and Extended Data Fig. 8f). Although microglia lipidomes from the healthy wild-type or Ccn1-cKO spinal cord were grossly similar (Fig. 4k and Extended Data Fig. 8g), we observed highly divergent injury-induced alterations in lipidomic profile across multiple lipid classes (Fig. 4k,l and Extended Data Fig. 8g–l). Microglia from the injured Ccn1-cKO spinal cord contained significantly increased levels of multiple lipid classes found in myelin and axonal debris, including phosphatidylethanolamine, sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine (Fig. 4l), echoing the increased levels of internalized myelin debris observed in WDM of the Ccn1-cKO spinal cord white matter (Fig. 3b–e) and revealing a profound disruption in microglial debris processing and associated lipid metabolism.

Following phagocytosis, excess myelin-derived cholesterol is converted into cholesterol esters and stored with triacylglycerols in lipid droplets35. In microglia, cholesterol esterification and lipid droplet biogenesis are adaptive lipid buffering responses to myelin debris uptake that enable efficient debris clearance and white matter repair33. Though our analysis did not permit for detection of free cholesterol, we found that microglia from the injured Ccn1-cKO cord contained a significantly lower proportion of cholesterol esters and triacylglycerols, relative to wild type, indicative of impaired lipid storage (Fig. 4l). Validating this result and interpretation, WDM from the Ccn1-cKO cord contained significantly fewer lipid droplets than their wild-type-derived equivalents (Fig. 4m,n and Extended Data Fig. 8m–r). The proportion of WDM containing lipid droplets was also significantly attenuated (Extended Data Fig. 8n). Thus, astrocyte CCN1 is critical for injury-induced accumulation of storage-associated lipids and lipid droplets in phagocytic white matter microglia.

In addition to being esterified and stored in lipid droplets, intracellular cholesterol can exist in a free state, which is actively effluxed via ATP-binding cassette transporters. We hypothesized that the accumulation of myelin debris-derived lipids, including free cholesterol in WDM of the injured Ccn1-cKO spinal cord, could result in amplified Abca1 expression, favouring cholesterol efflux over storage. We observed that Ccn1-cKO-derived WDM indeed express significantly higher levels of Abca1 than those from the wild-type spinal cord (Fig. 4o,p and Extended Data Fig. 8s). These data further verify microglia transcriptomic profiling and cholesterol efflux assay results demonstrating the direct CCN1-mediated suppression of microglia lipid efflux-related gene expression and efflux activity (Fig. 4a,b,i).

Together, these data show that coordination of injury-induced lipid metabolic reprogramming in debris-clearing microglia relies on astrocyte-derived CCN1. These CCN1-dependent alterations hinge on an adaptive lipid buffering response characterized by lipid droplet accumulation and reduced cholesterol efflux capacity that supports efficient uptake and intracellular digestion of lipid-rich debris.

A CCN1–SDC4 axis regulates microglial lipid storage

We sought next to investigate the receptor-dependent mechanism of action through which CCN1 regulates microglia lipid metabolism. We carried out CCN1-directed co-immunoprecipitation in microglia and identified binding partners by mass spectrometry proteomics. (Fig. 4q and Supplementary Data 5). Analysis of binding partners for known CCN1 receptors identified SDC4 (ref. 36), a transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan (Fig. 4q). Notably, Sdc4 expression was increased more than twofold in WDM of the injured spinal cord relative to healthy spinal cord microglia, as determined by snRNA-seq (Sdc4 log2-transformed fold change 1.09, adjusted P value = 6.4 × 10−6), which was verified histologically in the degenerating spinal cord white matter (Fig. 4r,s).

Given prior work linking SDC4 to regulation of lipid droplet dynamics37, we investigated whether CCN1 directly controls microglial lipid storage and whether this is dependent on SDC4. Stimulation of microglia with CCN1 led to an increase of about 400% in microglial lipid droplet accumulation (Fig. 4t,u and Supplementary Data 6), thus demonstrating a direct role for CCN1 in facilitating microglia lipid storage, as initially suggested by our in vivo microglia lipidomics and histological analyses (Fig. 4l–n and Extended Data Fig. 8m–r). This also provides functional validation of microglia transcriptomic profiling results demonstrating CCN1-mediated upregulation of key lipid storage enzymes and effectors (Fig. 4a,b). Remarkably, in alignment with CCN1 co-immunoprecipitation proteomics, the capacity of CCN1 to augment microglial lipid storage was abolished by SDC4 function-blocking antibodies (Fig. 4t,u and Supplementary Data 6).

Cumulatively, these findings suggest a CCN1–SDC4 signalling axis that regulates adaptive lipid buffering mechanisms in microglia. These results further establish astrocyte CCN1 as a direct and critical regulator of microglial lipid metabolic mechanisms that are necessary for the digestion of engulfed cellular debris and thereby the efficient clearance of debris from the degenerating white matter in the CNS.

Myelin degeneration induces astrocyte Ccn1

The nature of astrocyte-extrinsic mechanisms that trigger discrete reactivity states are not well understood. Using Ccn1 expression as a biomarker of a molecularly distinct white matter LRA reactivity state (Fig. 1l,m), we next explored the mechanism of its induction. Given that Ccn1-expressing LRAs localize to degenerating white matter, we investigated whether myelin debris is sufficient to induce astrocytic Ccn1 expression. We observed that intraspinal injection of CNS myelin triggered robust astrocytic Ccn1 expression (Fig. 5a,b and Extended Data Fig. 9a,b).

a,b, Ccn1+ astrocytes in mouse spinal cord lateral white matter following microinjection of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-conjugated myelin (a; scale bars, 250 μm (left) or 50 μm (right)) and quantification relative to vehicle control (PBS) (b; n = 4 mice per group, 3–5 sections per mouse; two-sided Student’s t-test). c, Schematic of saporin injection experiment to determine the mechanism of astrocyte Ccn1 induction. d, FluoroMyelin (yellow arrowheads) and SMI32 (white arrowheads) staining to detect myelin and axon degeneration following saporin (Sap) injections. Scale bars, 50 μm. e–g, Imaging (e) and quantification (f,g) of Ccn1+ astrocytes (e,f) and IBA1+ microglia (e,g) in spinal cord dorsal white matter (dWM) following saporin-mediated neurodegeneration. Ccn1+ astrocytes and WDM-like nodules are largely restricted to degenerated myelinated tracts in the CTB–saporin condition (n = 3 mice per treatment for 14 dpi and 4 mice per treatment for 28 dpi, 6–11 sections per mouse). Scale bars, 250 μm (main image) or 10 μm (inset). h,i, Ccn1+ astrocytes (white arrowheads) and nodules with IBA1+ microglia/macrophages (yellow arrowheads) in mouse spinal cord lateral white matter at 3 days (n = 6 mice per condition), 10 days (n = 6 mice per condition) and 25 days (n = 5 mice per condition) following microinjection of lysphophosphatidyl choline (LPC) (h), and quantification of Ccn1+ astrocytes relative to vehicle (PBS) (i). Scale bars, 50 μm. j, Spatial transcriptomics demonstrates enrichment of Ccn1+ astrocytes and WDM-like microglia within LPC-demyelinated corpus (data from ref. 42). k, Ccn1+ astrocytes (white arrowheads) intermingle with nodules containing IBA1+ microglia/macrophages (yellow arrowheads) neighbouring spinal cord white matter lesions in the mouse myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG35–55)-induced model of EAE. dpim, days post-immunization. Scale bars, 50 μm. l,m, Quantification of Ccn1+ astrocytes (l) and IBA1+ microglia (m) nodules per lesion at EAE onset (n = 4), peak EAE (n = 4) and in chronic EAE (n = 6) (6–32 sections per mouse). n, CCN1+ astrocytes are absent from white matter in healthy human spinal cord, but are present throughout the white matter in multiple sclerosis lesions (WML) and in lesion-remote normal-appearing white matter (WM). Scale bars, 250 μm. o, CCN1+ astrocytes in lesion-remote Wallerian degenerating corticospinal tract white matter in human SCI. Scale bars, 250 μm (main image) or 10 μm (inset). Graphs show mean ± s.e.m. In graphs of histological counts or continuous data, coloured data points represent the mean value for each biological replicate (individual mouse); grey data points indicate replicate measurements from individual tissue sections. Unless stated otherwise, statistical analyses were performed using two-way ANOVA on mean values from biological replicates with Holm–Sidak post hoc test. Exact P values are provided in the Source Data.

Injections into white matter inherently damage axons and their associated myelin, obscuring whether astrocyte Ccn1 expression is initiated by the degeneration of axons, myelin or both. To isolate this central mechanistic detail, we carried out intraplantar injection of saporin conjugated to cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) or isolectin B4 (IB4) to selectively degenerate myelinated or non-myelinated sensory afferents, respectively (Fig. 5c,d). We then quantitatively assessed astrocyte Ccn1 expression along degenerating afferent fibres innervating the cord. We observed that the degeneration of myelinated, but not non-myelinated axons resulted in significant astrocytic Ccn1 expression (Fig. 5e,f), which also preceded the arrival of WDM-like multicellular microglia nodules (Fig. 5e,g and Extended Data Fig. 9c,d).

A conserved white matter reactivity state

We next examined astrocyte Ccn1 expression in the context of demyelinating diseases and insults in mice and humans. Ccn1+ astrocytes were found throughout mouse spinal cord white matter lesions at 3 days following lysolecithin-mediated demyelination and persisted for at least 25 days thereafter (Fig. 5h,i and Extended Data Fig. 9e–g). Remarkably, Ccn1+ astrocytes were found to associate intimately with WDM-like microglia around lysolecithin demyelinated lesions (Fig. 5h,j). We also assessed astrocyte Ccn1 expression in the spinal cords of mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) inflammatory demyelinating disease (Fig. 5k,l and Extended Data Fig. 9h). Few Ccn1+ astrocytes were present at disease onset, and these localized mainly to normal-appearing ventrolateral white matter (Fig. 5k,l). In peak and chronic disease, Ccn1+ astrocytes were prevalent, concentrated around inflammatory white matter lesions, and adjacent to microglia nodules (Fig. 5k–m and Extended Data Fig. 9i).

We also evaluated astrocyte CCN1 expression in archival human spinal cord tissue from individuals with multiple sclerosis or SCI and neurologically healthy controls (Extended Data Fig. 9j). CCN1-expressing astrocytes were frequent in white matter associated with multiple sclerosis lesions and lesion-remote normal-appearing white matter, but rare in multiple sclerosis-associated grey matter and healthy spinal cord (Fig. 5n and Extended Data Fig. 9k,l). Corroborating findings from our mouse iSCI model, we observed CCN1+ astrocytes throughout human SCI lesion-remote Wallerian degenerating white matter, but not in neighbouring grey matter (Fig. 5o and Extended Data Fig. 9m).

Together, these results demonstrate that astrocyte CCN1 expression is: (1) an evolutionarily conserved response of white matter damage-reactive astrocytes; (2) induced by degeneration of myelin but not of axons; and (3) implicated in the regulation of debris-clearing phagocytes across divergent forms of CNS white matter damage and disease in mice and humans.

Discussion

The present work resolves multiple fundamental attributes of LRAs, including (1) their unique transcriptional identity; (2) their neuroanatomical regional heterogeneity; (3) the temporal evolution of transcriptional LRA reactivity states; (4) the roles of LRAs in local multicellular responses to CNS injury and in repair; and (5) the mechanisms that drive LRA reactivity states. Astrocytes exhibit regional heterogeneity across the spinal cord dorsoventral divide in development and adulthood38,39. Correspondingly, our results indicate that after SCI, LRAs acquire intraspinal region-specific reactivity states that are likely to have distinct functions and consequences. According to transcriptomic profiling, LRAs do not exhibit a simplified or dampened BFA-like response to SCI. Rather, LRAs acquire discrete reactivity states, altering expression of many hundreds of genes that are not detected in BFAs, underscoring that these intraspinal reactivity programmes are fundamentally distinct. Our findings suggest that divergent LRA reactivity states are linked to selective modulation of gene expression implicated in neurotransmitter sensing and buffering, as well as structural and functional synapse development. Overall, the exploration of how regionally restricted LRA reactivity states affect local circuit structure and function is essential to shaping next-generation treatments that manipulate spared regions of the injured CNS to promote neural repair.

White matter astrocyte reactivity is relatively understudied. We identified a type of regionally restricted, white matter degeneration-reactive LRA that exhibits distinctive expression of Ccn1. We find that astrocyte CCN1 regulates local microglia nodule formation, molecular phenotype, supports debris clearance ability and is critical for neurological recovery from SCI (Extended Data Fig. 10). Notably, the selective impact of astrocyte CCN1 depletion on sensory recovery, without affecting locomotor function, may reflect the spatial distribution of CCN1 expression and its association with degenerating tracts, which are unlikely to support compensatory locomotor processes. Defining mechanisms that coordinate debris clearance after white matter damage is essential for developing therapies that promote repair. Efficient intracellular processing of lipid-rich cellular debris by microglia is crucial for debris clearance and white matter repair25,33. We found that microglial metabolism of lipid-rich debris is dependent on molecular cues from local astrocytes. Our results support a working model in which astrocyte-derived CCN1 aids microglia-mediated debris clearance by enabling microglial metabolism of ingested cell debris via the SDC4-dependent modulation of mechanisms that buffer excess debris-derived lipids, specifically augmenting their sequestration into lipid droplets and restricting efflux (Extended Data Fig. 10). Beyond buffering excess lipids and preventing lipotoxicity40, lipid droplets serve as microglial energy stores35. Disruption of this pathway may impair debris clearance41, consistent with the stalled phagocytic phenotype in microglia from the injured Ccn1-cKO spinal cord. Collectively, our findings across multiple mouse models and human disorders show that CCN1 expression is an evolutionarily conserved astrocyte-derived cue induced by local myelin degeneration. This suggests the possibility that a pathological trigger that is common to multiple CNS disorders (myelin damage) may drive an astrocyte response with conserved consequences. Indeed, an important question raised by our findings is whether astrocyte CCN1-mediated signalling can be therapeutically harnessed to enhance clearance of white matter debris, restrict inflammation and promote white matter repair across a spectrum of CNS disorders and insults.

Our results indicate that after CNS injury, LRAs acquire heterogenous, evolving and spatially restricted reactivity states that are mediated by microenvironmental context-specific cues. We show that LRAs retain, but modify, their interactions with local cell types, and potently govern multicellular processes underlying degeneration-associated inflammation and tissue repair. This work strongly suggests that the manipulation of LRA reactivity states may be a viable path for limiting chronic neuroinflammation, enhancing functionally meaningful regenerative plasticity, and promoting neurological recovery after CNS injury and in disease.

Methods

Mice

Young adult male and female mice were used between 2 and 4 months of age at the time of experimental procedures. C57BL/6 J mice (JAX: 000664) were used for experiments requiring a wild-type background. For RNA-seq of astrocyte-specific ribosome-associated mRNA mice expressing RiboTag43 (JAX: 029977) were crossed to the well-characterized, astrocyte-specific Cre-driver line, mGfap-cre 73.1237 to generate mGfap-cre-RiboTag mice. mGfap-cre-RiboTag mice were crossed to Stat3-loxP mice10 to generate mGfap-cre-Ribotag-Stat3-loxP mice (Stat3-cKO). Astrocyte-conditional Ccn1-knockout mice were obtained by crossing the well-characterized, astrocyte-specific Cre-driver line Aldh1l1-CreERT2 (ref. 31) JAX: 031008 to the Ccn1-LoxP line32 (a gift from K. Lyons) to generate Ccn1-cKO mice. Aldh1l1-CreERT2 mice were crossed to the floxed-STOP-tdT (Ai9) reporter line to generate Aldh1l1-CreERT2::floxed-STOP-tdT mice. Cre recombinase expression was activated in young adult mice (6–8 weeks old) by administering tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648-1G, 20 mg ml−1 in corn oil) by subcutaneous injection (100 mg kg−1, once a day) for 5 days followed by clearance for 3 weeks so that no residual tamoxifen remained at the time of experiment initiation. All mice were housed in a facility with a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle and controlled temperature and humidity, and were allowed free access to food and water. Experiments were conducted according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cedars-Sinai medical centre.

Surgical procedures

All surgeries were performed on male and female young adult mice (8–12 weeks old) under general anaesthesia with isoflurane in oxygen-enriched air using an operating microscope (Zeiss), and rodent stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf).

Spinal cord injury

Laminectomy of a single vertebra was performed at spinal cord level T12. Incomplete iSCI by unilateral T12 hemisection was performed on the left side of the spinal cord using a microknife (Fine Science Tools). To be included in the study, mice exhibited complete unilateral hindlimb paralysis for the first three days following surgery. A T12 crush SCI was made using no. 5 Dumont forceps (Fine Science Tools) with a 0.4 mm spacer and with a tip width of 0.5 mm. T12 crush mice exhibited paralysis in both hind limbs. In each case, mice received the opiate analgesic buprenorphine subcutaneously before surgery and every 12 h for 48 h after injury. Mice were evaluated thereafter blind to genotype and experimental condition. Daily bladder expression was performed for the duration of the study or until voluntary voiding returned.

Injections of lysolecithin or myelin into the spinal cord

Five-hundred nanolitres of 1% lysolecithin or 1 mg ml−1 CFSE-myelin in PBS was delivered by intervertebral microinjection to the lateral spinal cord white matter at spinal cord level T12 (coordinates: 200 μm medial–lateral, 300 μm dorsal–ventral). Injections were carried out at 150 nl min−1 using finely bevelled glass micropipettes connected via high-pressure tubing (Kopf) to 10 μl gastight syringes under the control of microinfusion pumps (Harvard Apparatus). Needles were left in place for 6 min prior to being slowly retracted. An equal volume of PBS was injected into the contralateral white matter as vehicle control. Mice were euthanized at 3 days post myelin injection and at 3, 10 and 25 days post-lysolethicin.

Sciatic nerve injury

A small incision was made on the left hindlimb and the two heads of the bicep femoris muscle were gently separated to reveal the sciatic nerve. The sciatic nerve was released from the muscle and elevated using forceps. The isolated nerve was then clamped with haemostats for 10 s and then replaced under the muscle. Mice were euthanized seven days following sciatic nerve crush.

Saporin injection

Conjugated saponins were used to degenerate myelinated and unmyelinated fibres as previously described44. In brief, mice were anaesthetised and 8 μg (10μl of 0.8 μg μl−1 in PBS) of saporin (non-conjugated control), IB4-conjugated saporin (targets unmyelinated fibres) or CTB-conjugated saporin (targets myelinated fibres) was injected subcutaneously into the plantar surface of the left hindpaw foot pad using a 30G insulin syringe. Injections of IB4–saporin and CTB–saporin were considered successful if there was local swelling in the treated hindpaw for 24–48 h following injection. Mice were euthanized at 14 and 28 days after injection.

EAE induction and assessment

Active EAE was induced as described45 with modifications. Nine-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized subcutaneously in both hind flanks with 100 μg of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide (MOG35–55) emulsified in Complete Freund’s adjuvant containing 200 μg of killed mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Ra (Hooke labs) and injected intraperitoneally on days 0 and 2 with 110 ng pertussis toxin. Assessment of EAE was as follows: 0, no disease; 1, decreased tail tone; 2, hind limb weakness; 2.5, partial hindlimb paralysis; 3, complete hind limb paralysis; 4, front and hind limb paralysis; and 5, moribund state. Mice were collected at different stages of disease on the basis of the following pre-defined criteria: onset, partial or completely limp tail (score 0.5–1) at day 10 ± 2 days; peak, near or complete paralysis of hindlimbs with or without forelimb weakness (score 2.5–3.5) at day 14 ± 2 days; chronic, mice that reached a score of at least 2.5 (limp tail and incomplete paralysis of hindlimbs) no later than day 16 and collected at day 56.

Myelin purification and conjugation

Myelin was purified from adult C57BL/6 mice brains by sequential ultracentrifugation on discontinuous sucrose gradient and hypo-osmotic shock as previously described25. Brains were homogenized with a glass Dounce in 10 mM HEPES, 5 mM EDTA and 0.32 M sucrose. This was layered on 0.85 M sucrose in HEPES/EDTA buffer and centrifuged in a SW41 Ti rotor at 24,600 rpm for 30 min with acceleration and deceleration set to 1. The crude myelin fraction was removed from interface, resuspended in ice-cold distilled water, and centrifuged at 9,500 rpm for 15 min. This step was repeated two more times. The pellet was then dissolved in 0.3 M sucrose in HEPES/EDTA buffer and placed on top of 0.85 M sucrose in HEPES/EDTA. All centrifugation/resuspension steps were then repeated. The final pure myelin pellet was resuspended in PBS, quantified using a BCA assay, and resuspended to 1 mg ml−1 and then conjugated to CFSE as previously described46. Myelin (1 mg ml−1) was incubated with 50 μM CFSE at 37 °C for 15 min and then washed with 100 mM glycine in PBS at 14,000 rpm for 15 min, washed twice with PBS at 14,000 rpm for 15 min each and pellets were then resuspended to 1 mg ml−1 in PBS.

Hindlimb locomotor evaluation

A modified Basso mouse scale (BMS) was developed to evaluate the gradual functional recovery of distinct hind limb muscle groups after iSCI, over time, in freely moving mice. We converted the original BMS protocol47 of 5 locomotor categories with a maximal score of 9 into 12 locomotor categories (ankle movement, toe movement, knee movement, weight support, paw placement, dorsal stepping, missing steps, paw position on lift-off, paw position on initial contact, coordination, trunk instability and tail tone) with a maximal score of 37. Analysis was performed at days −5, 0, 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, 28, 42, 56, 70 and 84 dpi.

Cold thermoception behavioural evaluation

Hindpaw sensitivity to cold stimuli was evaluated using the acetone test48. Spontaneous thermoceptive behaviours were monitored for 1 min after a drop of acetone (~25 μl) was applied to the plantar surface of left or right hindpaw with the aid of a 22G flexible gavage needle attached to a 1 ml syringe. The total duration of acetone-evoked behaviours (paw withdrawal, biting, licking or scratching) was measured from videos reviewed in slow motion. Analysis was performed at days −5, 7, 28 and 84 dpi.

Von Frey testing

Mechanical sensitivity was assessed using the von Frey filament test. Mice were placed in individual elevated chambers each measuring 3.75 × 3.75 × 5 inches with a mesh floor. Mice were acclimated to the testing chamber for 5 days before beginning any measurements and allowed to acclimate for 15 min prior to the start of testing on data recording days. A set of 20 nylon Semmes Weinstein monofilaments was used for testing. In brief, a fibre was gently pushed against the surface of the skin from below. Filaments of increasing stiffness (0.02–2.0 g) were applied perpendicularly to the plantar surface of the hind paw with sufficient force to cause slight bending and held for 2–3 s. A withdrawal response is categorized as an indicator of nociception and is defined as paw withdrawal, paw lifting, paw rotation, sniffing, licking, scratching, shaking or rapid movement, was recorded, and subsequent filament selection followed the up-down paradigm. If a withdrawal response was observed, the next lower force filament was applied; if no response occurred, the next higher force filament was tested. This process continued until six responses had been recorded in a series bracketing the threshold. Data were analysed using the up-down Reader algorithm to determine the 50% withdrawal threshold, which was calculated using Dixon’s formula.

Tissue processing, immunohistochemistry and mRNA in situ hybridization

Mice were euthanized by barbiturate overdose followed by cardiac perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Spinal cords were removed, post-fixed for 4–8 h, and cryoprotected in buffered 30% sucrose. Spinal cords were blocked into 5 mm segments centred around the lesion epicentre, embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OTC) medium and stored at −80 °C until sectioning. Serial frozen sections of cervical (C8-T4), thoracic (T3-T12) and lumbar (T9–L3) segments (40 μm, transverse) were prepared using a cryostat microtome (Leica) and stored in antifreeze solution (glycerol, sucrose and TBS) at −20 °C until processed for evaluation by immunofluorescence and/or mRNA in situ hybridization as described9. Primary antibodies include: Rat-CD18 (1:100, Invitrogen), Rat-GFAP (1:1,000, Thermofisher), Rabbit-GFAP (1:1,000, Dako), Goat-IBA1 (1:1,000, Abcam), Rabbit-IBA1 (1:1,000, Wako), Rabbit-LPL (1:50, Abcam), Rabbit-PLIN2 (1:500, Progen), Goat-SOX9 (1:200, R&D system), Mouse- (1:3,000, Biolegend), Sheep-TREM2 (1:250, R&D systems), Rabbit-YAP1 (1:200, Protintech). Mouse primary antibodies were visualized using the M.O.M. (Mouse on Mouse) Immunodetection Kit (Vector Laboratories). Primary antibodies were selected on the basis of validation for fluorescence immunohistochemistry analysis in mouse tissue by the manufacturer, and/or by other investigators on the basis of peer-reviewed publications. Fluorescence secondary antibodies were conjugated to Alexa 488, Cy3 or Cy5 (all from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Nuclear staining was performed using DAPI (2 ng ml−1; Molecular Probes). Sections were cover-slipped using ProLong Glass mounting agent (ThermoFisher). When applicable, tissue sections were incubated in FluoroMyelin Green to label myelin and myelin debris (1:300) or the neutral lipid dye BODIPY to label lipid droplets (1:1,000) (ThermoScientific) prior to DAPI incubation.

Florescent in situ hybridization on fixed-frozen mouse spinal cord sections was performed using RNAscope probes and the Multiplex Fluorescent Detection Kit v.2 per manufacturer’s instructions (Advanced Cell Diagnostics). Mouse spinal cord sections were permeabilized with Protease IV. Probes used on mouse spinal cord tissue were as follows: Abca1 (522251), AldoC (429531-c2, 429531-c3), Arex (541871), Ak3 (454791), Boc (876211), Ccn1 (429001), Gfap (313211-c2, 313211-c3), Glipr2 (467171), Gpnmb (489511), Igf1 (443901-c2), Lair (509151), Prdm16 (584281) Scl1a3 (430781) and Thrsp (1090411). mRNAs of interest were labelled with the following fluorophores (Akoya): Opal 520 (FP1487001KT), Opal 570 (FP1488001KT), Opal 620 (FP1495001KT) and Opal 690 (FP1497001KT). Slides were then processed for immunohistochemistry or stained with DAPI before mounting. Human spinal cord tissue was permeabilized with target retrieval reagent and protease plus. Probes used in human tissue were as follows: CCN1 (4452081), GFAP (311801-C2) and SLC1AA3 (461081-C2). Sections were stained with DAPI and mounted with ProLong Glass or Vectashield mounting medium.

Reference to protein or gene names follow standardized guidelines for mouse and human as established by the Human Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) and the Mouse Genome Informatics (MGI) database. Here, human and mouse proteins are referred to in all upper case, non-italicized font (for example, CCN1, IBA1, TREM2); genes and mRNA is referred in all upper case, italicized for human (for example, CCN1) and first letter capitalized and otherwise lower case, italicized for mouse (for example, Ccn1, Gpnmb, Igf1).

Imaging

Images of tissue sections used for quantitative analyses were collected using an Apotome epifluorescence microscope with structured illumination hardware and deconvolution software (Zeiss). For whole spinal cord Ccn1 and microglial analysis, we generated 10× tiles of the entire spinal cord at a single z-plane. Microglial quantification was imaged at 20× (Trem2, LPL) with a z-thickness of 1 μm or 40× (FluroMyelin, SMI32, PLIN2, BODIPY, Gpnmb and Abca1) with a z-thickness of 0.5 μm. Similarly, images of astrocytes with subtype markers and were imaged at 40× with a 0.5 μm z-stack. Representative images for illustrative purposes were imaged on a Leica SP7 Confocal microscope at 20× or 63×.

Image analysis

Imaris image analysis software (v.10) was used to generate 3D volumes of surfaces of IBA1+ microglial and a marker of interest (for example, FluroMyelin, SMI32, PLIN2, BODIPY, TREM2). Overlap between IBA1 and marker surfaces (≤0.5 μm distance) was used to determine the proportion of microglia that were marker-positive. Similarly, overlap of marker-positive surfaces that were within an IBA1 surface (≤0.5 μm: TREM2, PLIN2, BODIPY, FluroMyelin, SMI32) determined the volume of marker present within microglia. Measurements were normalized to the total volume to IBA1 microglia and measurements were restricted to the spinal cord dorsal white matter unless stated otherwise. For YAP1 analysis, 3D surfaces were generated for all DAPI+ nuclei, YAP1, Gfap/Slc1a3 mRNA and Ccn1 mRNA. Astrocyte nucelli were determined by setting the overlap volume of DAPI and Gfap/Slc1a3 to 15. Astrocytes nuclei expressing Ccn1 were those containing an overlap volume of Ccn1 greater than 0.16. Finally, the YAP1 expression within the Ccn1+ and Ccn1− astrocytes was the volume of YAP1 (<0 μm) within these Ccn1+ or Ccn1− astrocyte nuclei.

Spatiotemporal analysis of Ccn1+ astrocytes and microglial nodules

Regional quantification of Ccn1+ astrocytes and IBA1+ microglial nodules was performed on 10× image tiles of transverse spinal cord sections using the cell counter plugin (Fiji). Transverse sections were only evaluated if they appeared cytoarchitecturally intact with normal-appearing white and grey matter anatomy. Initially, 8 anatomical reference points were used to align transverse spinal cord images: central canal; top of the dorsal white matter; bottom of the dorsal white matter; left and right lateral white matter; top and bottom of the central grey matter; the left and right sides of the central grey matter; the top of the dorsal horn grey matter on left and right sides, and the bottom of the ventral horns on left and right sides. For injured samples, the side containing the majority of Ccn1+ astrocytes or microglial nodules was labelled as left (ipsilesional). Next, Ccn1+ astrocytes were quantified as Gfap/Slc1a3 containing nuclei that contained at least 3 Ccn1 mRNA puncta (RNAscope). Similarly, microglial nodules were quantified as closely associated clusters of microglia containing more than three microglial nuclei25. At least two sections were quantified per mouse. Ccn1+ astrocytes and microglia nodule counts from different tissue sections were aligned to a common coordinate system using a custom python script. First, all reference and cell coordinates were linearly shifted such that the central canal was set at (0,0). The average of each reference point across all sections per spinal region were used to define a template spinal section which was then used to perform non-rigid transformation (ThinPlateSplineShapeTransformer from the OpenCV2 library) of all cell coordinates. For visualization, Ccn1 astrocyte/microglia counts were spatially binned per section using a 2D histogram (bin area 19.35 μm2) and counts per bin were averaged per mouse and then per condition. The resulting cell count per bin was then plotted.

For statistical comparison of time-dependent differences in WDM nodule formation between wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice, we employed a Conway–Maxwell–Poisson (COM–Poisson) generalized linear mixed model with a log link and fixed effects for group and time49. This model was selected to enable robust assessment of how nodule counts change over time in wild-type and Ccn1-cKO mice, and whether these changes differ by genotype. The COM–Poisson distribution accommodates both overdispersion and underdispersion in count data and accounts for the repeated-measures structure of the dataset, wherein multiple tissue sections were analysed per biological replicate at each post-injury time point. The model included fixed effects for group (Ccn1-cKO versus wild type), time (7, 28 and 90 dpi), and a random intercept for each mouse to account for within-subject clustering. The group-by-time interaction was formally tested using a likelihood ratio test comparing nested models with and without the interaction term. Post hoc pairwise comparisons of group (genotype) and time levels were conducted on the basis of model-derived estimated marginal means, with multiple testing adjustment using Tukey’s method. All hypothesis tests were two-sided with a significance level set at 5%. These statistical analyses were performed using R software (v.4.4.1). Mixed models were fitted using the glmmTMB package50, and marginal means were estimated using the emmeans package51.

Quantitative analysis of in situ mRNA hybridization

Quantification of RNAscope probe signal (mRNA) in astrocytes and microglia was carried as described52. In brief, thresholding of RNAscope probe signal was first carried out (Otsu method: Ccn1 and Gfap/Slc1a3; triangle method: Gpnmb and Abca1) and the area of pixels was then quantified within the soma of Gfap+/Slc1a3+ astrocytes, or IBA1+ microglia or microglial nodules, respectively. The area of Gfap/Slc1a3 and Ccn1 were analysed from the same astrocyte somas, whereas the area of Gpnmb, Abca1 and Sdc4 mRNA was then normalized to the size of the microglia or nodule.

Fresh spinal cord tissue collection for astrocyte RiboTag RNA-seq

Spinal cord tissue was isolated for astrocyte RiboTag RNA-seq as described9. In brief, wild-type (mGfap-cre-RiboTag) and Stat3-cKO (mGfap-cre-Ribotag-Stat3-loxP) mice were perfused with ice-cold PBS with heparin and spinal cords were dissected out. Three millimetres of spinal cord rostral (T9–T11) and caudal (L1–L3) to the lesion epicentre were then rapidly removed, snap-frozen in dry ice and stored at −80 °C until processing for RiboTag RNA-seq. Spinal cords were collected at 3, 7, 14 and 28 dpi and anatomically equivalent regions of spinal cord were isolated from age- and genotype-matched healthy controls.

Astrocyte ribosome-associated mRNA isolation, RNA-seq and analysis

Astrocyte ribosome-associated mRNA was isolated using our previously established methods9. In brief, fresh frozen spinal cord tissue was homogenized and haemagglutinin (HA) immunoprecipitation was carried out to purify of astrocyte ribosome-associated mRNA. Astrocyte RNA integrity was analysed using the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) with the RNA Pico chip, with RNA integrity number (RIN) ≥ 8 for all samples. RNA concentration was determined using the RiboGreen RNA Assay kit (Life Technologies). cDNA was generated from 10 ng of RNA using the Universal plus mRNA-seq Kit (Nugen). The workflow consisted of poly(A) RNA selection, RNA fragmentation and double-stranded cDNA synthesis using a mixture of random and oligo(dT) priming, followed by end repair to generate blunt ends, adaptor ligation, strand selection and PCR amplification to produce the final library. Multiplexed sequencing was performed using the NovaSeq 6000 sequencer (Illumina) on a NovaSeq S2 flow cell to produce 50 bp paired-end reads. Data quality was assessed using Illumina SAV and demultiplexing was performed using Illumina Bcl2fastq2 v.2.17. Sequences were aligned to the mouse mm10 genome using STAR aligner (v.2.4.0j). Average percent of uniquely mapped reads was 79 (±8.7)%. Read counts were determined using HT-seq (v.0.6.0). At least 4, and in most cases 6 samples were evaluated per experimental condition. Genes not expressed in minimum of 10 samples (5 counts or more) or average fragments per kilobase per million mapped fragments (FPKM) below 0.75 were filtered out from further analysis. Differential expression analysis (DEA) was conducted using the Bioconductor EdgeR package (v.3.6). DEGs were determined using FDR at 5%. To identify co-regulated astrocyte-enriched genes across time after injury, a gene-gene correlation matrix was constructed using genes that were significantly enriched in astrocytes with a logFC >1 and FDR P ≤ 0.05 at any time point. Astrocyte-enriched gene expression was identified by comparing astrocyte HA immunoprecipitation-derived ribosome-associated mRNA to whole-tissue mRNA (HA immunoprecipitation input-derived mRNA). Astrocyte versus whole-tissue DEA identified 1249 astrocyte-enriched DEGs, which were used as input for a spearman correlation using log2FC changes values from iSCI versus healthy DEA and kmeans clustered into 11 gene modules. Genes in each module were used as input into gene ontology (GO) using Enrichr (GO_Biological Process_2018 database).

LRA gene expression data were compared to multiple other spinal cord astrocyte transcriptomics data sets from SCI and other non-traumatic CNS insults and disorders: BFAs17, ALS53, LPS9 and EAE54. A composite list of DEGs (log2 fold change versus healthy) across all datasets was compiled (9,558 DEGs) and used for all downstream analyses. Principal component analysis was performed as a descriptive visualization of global relationships across datasets, in conjunction with gene-level analyses of DEG overlaps, directionality, and functional groups. Together, these complementary approaches allowed us to assess both overall transcriptomic relationships and specific gene-level distinctions. For comparison between LRAs and BFAs, LRA 3 and 7 dpi were compared to BFA 2 and 5 dpi, respectively. DEG information was available for 14 and 28 dpi in both datasets. These data were used to tabulate the proportion of LRA DEGs that were either also significantly upregulated, downregulated, oppositely regulated, or not regulated in BFAs at each time point.

Nuclei isolation

iSCI mice were perfused with ice-cold PBS with heparin at 3, 7 or 28 dpi, spinal cords dissected out and 3 mm of spinal cord rostral (T9–T11) and caudal (L1–L3) to the lesion epicentre were then rapidly removed, snap-frozen in dry ice and stored at −80 °C. An anatomically equivalent region of spinal cord (T11–L1) was isolated from age- and genotype-matched healthy controls. Frozen tissue was homogenized in homogenization buffer (320 mM sucrose, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630, 5 mM CaCl2, 3 mM magnesium acetate, 10 mM Tris, Roche Protector RNAse Inhibitor, Complete Roche Protease Inhibitor v.12, 0.016 mM PMSF, 0.166 mM β-mercaptoethanol; pH=7.8). Nuclei were isolated from the homogenate by iodixanol gradient and resuspended in 1% BSA solution before proceeding immediately to 10x snRNA-seq.

snRNA-seq

snRNA-seq was performed using 10x Chromium Next GEMSingle Cell 3 (v.3.1) per manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were loaded to capture 10,000 nuclei per sample. During library preparation, the initial cDNA amplification was run for 13 cycles, which was found to be optimal for 10,000 nuclei. Following library preparation, quantitative PCR was run to quantify library concentration and samples were pooled to equivalent concentrations. Initially, a shallow sequencing run of the pooled libraries at ~20% sequencing saturation, the results of which informed library re-pooling in order to normalize nuclei number within the libraries to obtain ~40,000 reads per cell. Sequencing was performed by NovaSeq (Illumina) at 2 × 150 base pair reads at 150 pM (average reads per sample: mean: 2.9 × 108 ± 1.1 × 108).

snRNA-seq data analysis