Abstract

With the increasing use of microgrids, fault identification remains a significant challenge for microgrid protection. Overcurrent protection is the most widely used type of protection in the grids. Also, deep neural networks (DNNs) are used as suitable solutions to improve fault classification accuracy. However, some parameters can affect the performance of the deep learning-based fault detection and location (FDL) schemes. This paper presents a protective agent (PA)-based fault classification method using intelligent electronic devices (IEDs) and hybrid DNNs along with various parameters’ impact investigation. First, an FDL scheme based on two types of DNNs (single and hybrid types of layers) and PAs will be presented. Then, we analyze various overcurrent-based protection scenarios and their different parameters’ impact on the proposed scheme. In the next stage, the impact of different parameters including adding laterals to the microgrid, adding IEDs to the protection plan, improving the structure of the DNNs, protection scheme structure, and data transfer type on the proposed scheme are investigated in a data analysis and a comprehensive sensitivity analysis. The results demonstrate that the lowest and highest accuracy of the proposed algorithm in the studied scenarios in the fault detection section is 95.54% and 99.96%, in the fault type and phase detection section, is 95.56% and 99.86%, and for the fault location error is 6.51% and 1.27%, respectively. In all scenarios, due to the use of hybrid DNNs with two types of layers, the accuracy of DNN-2 was higher than DNN-1. Also, the results in the sensitivity analysis show that despite the high accuracy of the proposed scheme, some parameters significantly impact the accuracy of the DNNs outputs. We performed simulations using three software: DIgSILENT Power Factory, MATLAB, and Python (with Tensorflow and Keras libraries).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microgrid protection

Integrating machine learning into microgrid issues can enhance microgrid reliability and efficiency. Microgrid challenges encompass planning and management, reliability, stability, power quality, voltage and frequency control, and protection1. Machine learning tools can help address some of these challenges including microgrid protection (fault classification). The fault current magnitude in the grid-connected mode is about five times that of the islanded mode. However, the presence of inverter-based distributed generations (IBDGs) makes relays unable to detect faults in microgrid islanding mode. Hence, a proper protection scheme is necessary to safeguard the microgrid. Some studies in the state of the art have investigated different protection schemes for various types of grids such as changing settings without communication scheme2, centralized adaptive protection methods3,4, differential-based adaptive protection scheme5, FCL-based protection methods6,7,8, variables comparing-based method9, two-time dial setting-based protection plan10, protection using signal injection11, investigation of the selectivity problem for an overcurrent-based adaptive protection scheme12, and multi-agent-based hybrid adaptive protection13. However, one of the challenges of microgrid protection is fault classification. In recent years, some researchers have used different methods for fault identification in microgrids.

Fault detection and location approaches in different networks

Fault detection, identification, and fault location are crucial for protecting microgrids, with three primary objectives being fault detection (FD), fault type and phase identification (FT and FP), and fault location (FL). Accurate fault location can help with service restoration, reducing both system downtime and restoration efforts14. While research has explored using machine learning tools for microgrid protection, it has not yet fully addressed all protection challenges. In the following, schemes, methods, and approaches for fault detection and classification in different types of faults and networks are investigated. In15, a method was applied to smart grids to detect and locate faults in the nodes. The method injects a high-frequency current signal into the network to impose voltages on the nodes (about 1 V according to EN50065-1) and determine changes in line impedance. The authors in16 have proposed a fault detection, identification, and repair algorithm based on the IEC-61,850 protocol called GOOSE, which reduces the time required for definite fault detection. In17, a data-driven method is suggested for fault classification in smart grids. The algorithm, called Matching Pursuit Decomposition (MPD), is used to extract features in the frequency-time domain. The accuracy of the MPD algorithm is compared to other tools such as artificial neural networks (ANN) and support vector machines (SVM).

In other research studies, the authors18 have used Power Line Carrier (PLC) devices installed along the lines to identify and locate high-impedance faults (HIF) in the distribution networks. Also, a new algorithm based on detecting waveform distortion in the time domain using the theory of solid dielectric failure has been proposed to detect HIFs by the authors of19. An intelligent protection scheme for microgrids using combined wavelet transform and decision tree is presented in20. First, effective features were extracted from current signals of the fault and non-fault events using wavelet coefficients and then these features were used for training decision tree classifiers to detect and classify faults. In21, the authors proposed a protection algorithm for smart grids that includes wind and solar distributed generation resources. The proposed algorithm uses the mutual alienation coefficients between the current signals to detect and classify faults, which enables it to detect various faults in about a quarter of the cycle. In another research, authors in22 proposed an approach for fault classification in microgrids using optimal wavelet functions matching pursuit. This research study uses a combination of wavelet functions and machine learning methods including decision tree, K-nearest neighbor, support vector machine, and naïve Bayes to classify faults in the microgrid. A protection scheme based on artificial neural networks has been proposed in23, which uses the Stockwell transform as a signal processing tool for fault classification. In another work, authors in24 presented a fault detection and location method using deep neural networks and wavelet transform in the microgrid and distribution networks. In this study, different events of each line are used to train the classifier corresponding to that line. Also, a fault detection and classification scheme for microgrids using recurrent neural networks and radial basis function neural networks is presented in25. Authors in this study utilized current signal features to train the studied neural networks.

Some methods use the zero-sequence current component to detect the faulty part in distribution networks with inverter-based distributed generation resources. A faulty feeder detection scheme using the zero sequence current space relative distance between two parameters is proposed in26. These parameters include the increment of each feeder and an estimation of the faulty path generated by Kalman filtering. Also, authors27 presented a faulty feeder detection approach for single-phase to ground faults in distribution networks based on transient energy and cosine similarity and using transient zero-sequence current. In this work, the fault possibility of the feeders has been calculated by cumulative density function, and if the value of this function for each of the feeders is higher than the other, it is recognized as a faulty feeder. However, like some other studies, the distribution feeder has been diagnosed as a faulty part.

In other research studies, authors in28 have proposed a novel superimposed voltage energy-based scheme to detect and locate single phase-to-ground (SPG) faults in distribution networks. This research study uses wavelet packet transform and general regression neural networks (GRNNs) to classify different SPG faults and capacitor switching. Authors in29 have presented a fault detection and classification method to design a protection scheme for utility grids with high penetration of wind and solar energy. In this study, different feature extraction methods including Stockwell transform, Hilbert transform, and alienation coefficient are employed to detect and classify faults. A customized artificial neural network (ANN)-based fault detection scheme for a distribution system is presented in30. In this research study, the up-pyramid and down-pyramid models of ANN are combined as a custom pyramid model. A kernel principal component analysis-based single-phase earth fault detection model using multi-layer perceptron neural networks is proposed in31. In this study, different optimization strategies, parameter tuning, and regularization optimization analyses are performed to investigate the proposed scheme performance. Also, authors in32 proposed a multi-agent protection scheme for microgrids using deep learning that classifies different types of faults with a high accuracy. Considering some reviewed research in this section, data mining and machine learning-based methods have significantly advanced, however, there have been unprecedented developments in machine learning-based studies, particularly in the use of DNNs and different parameters’ impact analysis. However, one of the important contributions in this paper is investigating different parameter’s impact on the DNN-based fault classification accuracy.

In this paper, first, a protective agent-based FDL scheme using IEDs and DNNs for microgrids has been presented. The proposed scheme can develop FDL by training the features of the three-phase currents and fault current sequence components to hybrid DNNs with dense and gated recurrent unit (GRU) layers using different faults and non-faults cases that the outputs of the trained deep neural networks are FT, FP, and FL. This scheme is implemented on different types of overcurrent-based protection plans and scenarios. For all scenarios, the proposed scheme has been implemented using deep neural networks, and its accuracy for each of them has been investigated, comprehensively. In general, 8 protection scenarios are defined for FDL in the CERTS microgrid. In these scenarios, the impact of using measurements and circuit breakers at different points of lines and laterals and other parameters including adding laterals to the microgrid, adding IEDs to the protection plan, improving the structure of the DNNs, protection scheme structure, and data transfer type (local or communication-based) on the proposed scheme has been investigated. Then, a data and sensitivity analysis are performed, comprehensively. The proposed scheme process was performed in three software and programming languages, including DIgSILENT Power Factory, MATLAB software, and Python programming language. Table 1 lists the specifications of the relevant studies conducted using different ML-based approaches.

The contributions of this work are presented as follows:

-

Proposing a protective agent-based FDL scheme using IEDs, two types of DNNs (single and hybrid types of layers including dense and gated recurrent unit), and information on numerous fault and non-fault cases to classify faults (fault detection, identification, and location) in the CERTS microgrid.

-

Introducing and simulating eight overcurrent-based protection plans (8 scenarios) for the studied microgrid, and investigating different parameters accuracy of the proposed approach in detail. In these scenarios, we have used measurements (IEDs) and breakers at various microgrid locations in different protection plans.

-

Analyzing different parameters’ impact on the proposed scheme comprehensively including the impact of types of microgrid protection plans, lateral existence, location of measurements, type of data transfer, etc. In this way, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis of the proposed scheme concerning different parameters including adding measurements, adding laterals, measurements locations, how to use data, etc. have been performed.

-

Validation of the proposed scheme’s performance using extensive simulations across three software and platforms including DIgSILENT Power Factory, MATLAB, and Python (Tensorflow and Keras libraries). The results are presented in numerical and graphical forms.

This paper is divided into several sections, with the second section introducing the microgrid that is under study. The third section examines the different aspects of the PAs-based proposed scheme, and deep neural networks that have been utilized, and outlines the various scenarios that have been developed. The simulations and numerical results are then analyzed in the subsequent section. In the fifth section, a data analysis and a comprehensive sensitivity analysis are conducted for all of the scenarios that have been examined. Research requirements including simulation information, implementation requirements, and a comparative study are presented in the sixth section. Finally, the paper concludes with a discussion of the results and their implications.

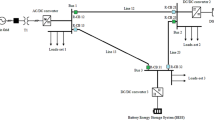

The studied microgrid

In this study, the investigated microgrid structure is based on the CERTS microgrid40. Figure 1 shows the modified version of the microgrid. The microgrid can operate in different topologies such as radial or loop. We have used three distribution generation resources in the microgrid, including two inverter-based distributed energy resources (IBDGs); a PV and battery energy storage system (BESS), and a typical diesel synchronous generator (SG). Six loads have been distributed in the microgrid. Lines 12, 34, 56, and 78 are of AWG2 type, and line 23, is of AWG00 type. Laterals 12, 23, 34, and 56 are located in 50% of lines 12, 23, 34, and 56 respectively. Lateral 23, is of AWG2 type, and laterals 12, 34, and 56 are of AWG00 type. The parameters of the studied microgrid are listed in Table 222. The understudy microgrid was modeled in DIgSILENT Power Factory software. The method described in41 was used in this study to detect islanding conditions.

The IBDGs are connected to the microgrid via inverters that convert DC voltage to AC. Also, a small scale synchronous generator is installed at Bus 3. The inverter of the PV-based DG operates as a current-controlled voltage source inverter. In grid-connected mode, it injects current according to its available power while synchronizing with the grid’s voltage and frequency. Considering that the grid-forming inverter is responsible for controlling the frequency and voltage of the microgrid in the islanded mode, one of the inverters connected to the distributed generation resources should work as a reference and control the voltage and frequency in the islanded operation mode. In this way, the inverter of the battery energy storage system (DG-BESS) acts as a grid-forming unit, primarily responsible for frequency regulation and dynamic power balancing in islanding conditions.

Investigation of different aspects of the proposed protective Agent-based scheme

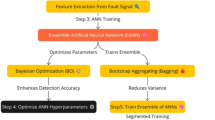

In this paper, we introduce a PAs-based fault classification scheme using IEDs, DNNs and consider different scenarios. In this section, the procedure details will be presented. Figure 2 shows the general algorithm of the proposed scheme. A total of 118,400 fault cases and 8,192 non-fault cases have been simulated for all scenarios that have been investigated in the next subsection in detail. Also, the discrete wavelet transforms of family Db and Sym with different types and levels of decomposition have been utilized to extract statistical features.

Fault and Non-Fault cases

An important factor to consider for the presented scheme is the number of fault and non-fault cases in the studied microgrid. To ensure comprehensive analysis, simulations were conducted for all scenarios with fault and non-fault cases, which are detailed in Tables 3 and 4. Since the laterals may have different structures in each scenario, the fault cases are separately specified for the faulty line parameter. These tables provide information on the fault and non-fault events that were carried out on the lines and laterals using the EMT simulation tool in DIgSILENT Power Factory software. The relay currents were then stored as an initial dataset, which was preprocessed using discrete wavelet transform (DWT) and extracting six statistical features for further analysis. At this stage, two families of wavelet transforms, namely Daubechies (Db) and Symlets (Sym), were employed with different decomposition levels (L). For each wavelet transform applied to the data extracted from fault and non-fault conditions, a total of (L + 1) approximation and detail coefficients were obtained. More information related to the used DWT families, type, and level and the statistical features are presented in Table 5.

Fault detection and location scheme using IEDs and DNNs

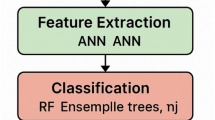

This step involves designing and creating deep neural networks for the protective agent-based FDL method. These DNNs are trained and tested using simulation results of different fault and non-fault cases after preprocessing. This study employs two structures for the PAs-based FDL scheme (Fig. 3). The first structure (DNN-1) utilizes Dense layers, while the second structure (DNN-2) utilizes a hybrid structure including Dense and GRU layers. The wavelet coefficients are denoted by C, the number of IEDs or measurements’ parameters that transfer information for protection agent (PA) in each zone is represented by M, and SCis indicates the number of neurons in each scenario. Details of the last layer for each structure are shown in Fig. 4. While more structures could have been employed, only two were used for this study, and the possibility of using more structures is a topic for future work. For fault classification, three deep neural networks have been created for each structure of the presented scheme. The last layer of the deep neural networks in Fig. 4 for fault detection has four neurons that indicate the FT and FP. The number of neurons in the last layer is NL for deep neural networks related to locating the faulty line, depending on the number of lines and laterals in each scenario. Furthermore, for fault location, the number of neurons in the last layer is 1 neuron, which is a regression indicator between 0 and 1, showing the percentage of the line or lateral where the fault occurred. Table 6 provides some of the parameters used in the training and validation process of the deep neural networks.

Introducing the Overcurrent-based protection plans (Scenarios) in the FDL process

An important aspect addressed in this study is the evaluation of the impact of the protection plans with different characteristics on the accuracy of the PAs-based FDL scheme. To this end, the presented scheme considers multiple overcurrent-based protection structures and different IEDs locations across 8 scenarios and examines the performance of the proposed scheme for each plan and scenario. Figure 5 illustrates the various overcurrent-based protection structures used in this study. Additionally, different protection plans are employed for transmitting information from IEDs to PAs (each PA includes Sampling Window (SW), DWT Feature Extraction (DWT FE), and DNN) for FDL using DNNs. The characteristics of the 8 examined scenarios are summarized in Table 7. It should be mentioned that although we know that cut-out fuses are usually used in lateral branches, to investigate all states of the PA-based FDL scheme, in some scenarios of this study, the IEDs, measurements, and breaker have been used in the lateral branches.

Performance analysis of different scenarios of the proposed PA-based FDL scheme (Numerical Results)

In this part, the protection structure of each scenario is analyzed separately. In each scenario, the operation of different equipment is described in the related protection plan. In some scenarios, communication protocols (including IEC-61850) have been utilized for the communications between IEDs, PAs, breakers, and higher layers including substation layer. Figure 6 shows different microgrid structures in the investigated scenarios of the proposed scheme. In the figures and the text, the R represents related IEDs.

In each of the scenarios, four important issues are analyzed: the structure of the micro-grid, the implemented protection plan, the description of the protection plan, and the accuracy of the DNNs outputs. Eight scenarios will be investigated in this part. The analysis was performed using DIgSILENT Power Factory software, and the fault and non-fault cases were programmed using DIgSILENT Programming Language (DPL). The output parameters were subjected to feature extraction (FE) using DWT in MATLAB software, and the DNNs were created, trained, and validated using Python (with TensorFlow platform and Keras library). The numerical results and simulations for each scenario are presented in the following subsections. It’s important to note that scenarios 2 and 5 were not separately analyzed in this section because they are slightly different from similar scenarios. However, their numerical results have still been included in the results analysis section for completeness. Also, in the tables of this section, the performance results of the forward and reverse PAs in each line are presented.

The first protection plan analysis (The first Scenario)

In the first scenario, 8 IEDs are used to observe the microgrid. Figure 6 (a) depicts the microgrid protection structure in this scenario. Protection agents (PAs) are installed on either side of each transmission line. During a fault condition, the IEDs send current information to the respective PAs, which then use a pre-trained DNN to detect fault events. The FDL process on line 23 in the first scenario is depicted in Fig. 5 (the first scenario), which shows that, in a fault event, the line forward IED (R-23) records a sampling window consisting of 64 samples of current. This window is continuously sent to PA, which starts the preprocessing of the raw current. After calculating the output coefficients of line currents, feature extraction is performed by applying various statistical features to these coefficients. The extracted features are then processed using DNN, and upon detecting a fault, a trip signal is sent to CB-23. A similar process is also carried out on the other side of line 23, where PA-32 sends a trip signal to CB-32. This approach ensures that the faulty line is disconnected. In this scenario, the data transfer type from PAs to CBs is local. It means the PAs send trip signals to the related CBs on the same bus. Also, the PAs system for the FDL process is decentralized. To further enhance the reliability of the fault detection process and reduce the misdetection of the PAs, the PAs communicate with each other, but not for the main fault detection process.

This process is also performed for other scenarios with some differences. The accuracy of the PAs in this scenario is listed in Table 8, where it can be observed that the accuracies are high. Additionally, the performance of DNN-2 is better than DNN-1 due to the hybrid structure of Dense and GRU layers.

The third protection plan analysis (The third Scenario)

The microgrid structure in the third scenario is presented in Fig. 6 (c). The fault classification strategy on the lateral branches is different in the third scenario. In this case, PAs are placed on both sides of the main lines, and they are responsible for detecting faults on the lateral branches. A separate DNN is pre-trained by the PA to detect faults on the lateral branches in this scenario. Figure 5 (the third scenario) shows the details of the procedure for line 23 and lateral 23 in the third scenario. In the event of a fault occurring on lateral 56, the PA-23 utilizes the measured current of R-23 as input to a similar process described above. The accuracy of the proposed plan in the third scenario is listed in Table 9. Although the accuracy of the DNNs outputs in the laterals has slightly decreased due to the removal of lateral IEDs, it is still acceptable.

The fourth protection plan analysis (The fourth Scenario)

In the fourth scenario, the impact of multiple lateral branches on FDL scheme was investigated by adding two lateral branches to each transmission line. Each lateral branch was equipped with an IED and a CB, located at the beginning of the branch. The microgrid structure in the fourth scenario is illustrated in Fig. 6 (d). In summary, there are 16 PAs for monitoring the microgrid, and each of them disconnects the faulty part in case of a fault. Figure 5 (the fourth scenario) shows the details of the FDL procedure on line 23 in the fourth scenario. However, the accuracy of the DNNs outputs in laterals has slightly decreased in the fourth scenario. This scenario may prove expensive in practical applications due to the need for IEDs and circuit breakers in the laterals. Table 10 summarizes the performance of the method in this scenario.

The sixth protection plan analysis (The sixth Scenario)

The sixth scenario involves a microgrid with one lateral branch as depicted in Fig. 6 (f). In this scenario, just one PA in each line is responsible for processing information and fault classification in the decentralized or centralized procedure. The protection procedure, as shown in Fig. 5 (the sixth scenario), involves the continuous observation of the microgrid by one IED in each zone and we do not use IEDs R-21, R-32, R-43, and R-65 information in the fault classification process. The faulty line detection DNN is a classification DNN with two output neurons for the decentralized procedure and NL neurons for the centralized procedure, where only one of them is active in each situation to identify faulty line within the protection zone. In the decentralized procedure, if the fault is on the main line, the first neuron will be activated, and two circuit breakers isolate the faulty line. On the other hand, if the fault is on the lateral 23 − 0, the second neuron will be activated, and the CB-23-0 disconnects the lateral. However, in this scenario due to the reduced number of some parameters and features, IEDs, and PAs, the accuracy of FDL is lower than in some scenarios, as indicated in Table 11.

The seventh protection plan analysis (The seventh Scenario)

The microgrid structure in the seventh scenario (depicted in Fig. 6 (g)) is similar to the third scenario. However, the protection plan for the FDL is different. The IEDs of the line are utilized for detecting and locating faults in the transmission lines, whereas the difference in current values of the IEDs in the lines is employed for fault classification in the laterals since there are no IEDs at the laterals. According to the protection scheme illustrated in Fig. 5 (the seventh scenario), If a fault occurs on the lateral 23 − 0, the processing units receive information from R-23 and R-32, and the fault on the lateral 23 − 0 is calculated using the difference of these currents. Subsequently, a DNN is employed to identify the location of the fault. Table 12 presents the accuracy of the FDL in this scenario.

The eighth protection plan analysis (The eighth Scenario)

The microgrid in the eighth scenario has four transmission lines and no laterals (Fig. 6 (h)). However, the protection scheme is different from previous scenarios as the IEDs are distributed throughout the microgrid and send information to a supervisory remote control unit (SRCU) located in the substation layer or system layer. The DNNs are then used for the FDL based on the information and parameters of the IEDs. The microgrid terminals do not use deep neural network processors in this scenario, which is an advantage, but there is a disadvantage of reduced reliability due to the use of a central processor (Centralized system). This scenario requires the use of telecommunications using the IEC-61850 protocol. The protection procedure diagram for this scenario is shown in Fig. 5 (the eighth scenario), and the accuracy of deep neural networks is presented in Table 13, indicating high accuracy for all lines in the central processor.

Analysis of the results and comprehensive sensitivity analysis

Analysis of the results

This study has analyzed various scenarios for PA-based fault detection and location scheme in the studied microgrid. Table 14 lists the average accuracy of the investigated scenarios along with the PAs’ detection time in the fault detection process, and Fig. 7 compares the average accuracy of the scenarios in terms of fault detection, FT and FP identification, and fault location. Also, Table 15 lists the misclassification contribution to the total error for fault detection by DNN-2. For example, in Scenario 3, where the average fault detection error for the validation data in the protective agents is 1.74%, among the cases where the fault actually occurred on Line 12, 0.75% were misclassified as faults on Lateral 12 − 0, and 0.2% were misclassified as faults on other lines and laterals. Conversely, among the cases where the fault occurred on Lateral 12 − 0, 0.44% were incorrectly identified as faults on Line 12, and 0.18% were attributed to other lines and laterals. Furthermore, when the fault occurred on lines other than Line 12 and Lateral 12 − 0, 0.17% were incorrectly classified as non-fault cases. This implies that the protective agent corresponding to Line 12 did not detect faults that were outside its protection zone. Although these cases are counted as misclassifications, the final decision—i.e., the non-operation of CBs associated with protection zone 12—is technically correct. The protective agents also correctly classified the non-fault condition in the cases where no actual fault had occurred.

In this study, we implemented a PA-based protection FDL scheme using IEDs and hybrid DNNs in the microgrid, considering factors such as the existence of the laterals, different DNN structures, and the location of the IEDs. Table 16 presents the impact of different parameters on the accuracy of the proposed scheme. While the accuracy of the scheme depends on various parameters, the results demonstrate that the accuracy is high and acceptable in all scenarios. The investigation provides valuable insights into the PA-based protection schemes for different overcurrent-based protection strategies. As mentioned before, the impact of four critical parameters on the accuracy of the approach has been analyzed. These parameters include adding laterals to the microgrid, adding measurements (IEDs) to the protection plan, improving the structure of the deep neural networks, and data transfer type in different scenarios. Figure 8 illustrates the impact of these parameters on the accuracy of DNNs-1, while Fig. 9 shows their impact on the accuracy of DNNs-2. According to the results presented in Figs. 8 and 9, the parameter with the most positive impact on the accuracy of the scheme is the improvement of the DNN structure, which includes the training, evaluation, and structure of the DNNs. This impact was observed in all scenarios. The second parameter is the addition of measurements (IEDs) to the microgrid laterals, which has increased the accuracy of fault detection, FT and FP identification, and fault location in three parts. On the other hand, the addition of laterals has caused a decrease in accuracy (in a general trend), and this can be further investigated in future studies. The fourth parameter, which is the data transfer type, has no significant impact on the accuracy of the PA-based FDL scheme. However, the results of the scenarios in different data transfer types are presented in the next section. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing the deep neural network structure and adding IEDs and measurements to improve the accuracy of fault detection and location.

Table 17 presents a statistical analysis of the results of all scenarios for both DNN-1 and DNN-2 structures. It includes the minimum accuracy (Min), the maximum accuracy (Max), the average accuracy (Average), the standard deviation of accuracy (SDEV), and the accuracy range (Max-Min) (AR). Additionally, it provides the specifications of the protective agent (PA) that had the highest and lowest accuracy in each scenario. For instance, the scenario with the lowest fault detection accuracy is related to PA-23 for the fault on lateral 23 − 0 (95.54%), which corresponds to the sixth scenario. The lowest accuracy in the fault detection section is related to PAs 23 and 34 in the sixth scenario for faults at La23-0 and La34-0 in DNN-1 and DNN-2, respectively, and the highest accuracy is related to PAs 23 and 32 in the first scenario for faults at Lines 23 and 56 in DNN-1 and DNN-2, respectively. In the fault type and phase detection section, the lowest accuracy is related to PAs 23 and 32 in the sixth and seventh scenarios for faults at La23-0 in DNN-1 and DNN-2, respectively, and the highest accuracy is related to PAs 21 and 23 in the fourth and first scenarios for faults at Lines 12 and 23 in DNN-1 and DNN-2, respectively. Also, in the fault location section, the lowest accuracy is related to PAs 56 and 23 in the sixth scenario for faults at La56-0 and La23-0 in DNN-1 and DNN-2, respectively, and the highest accuracy is related to SRCU and PA 43 in the eighth and fourth scenario for faults at Lines 12 and 34 in DNN-1 and DNN-2, respectively.

As shown in Table 14, Figs. 8 and 9, although in many cases, the accuracy of PA-based FDL was high accuracy, the addition of laterals to the microgrid has reduced the accuracy of the presented scheme. In this regard, we have performed a sensitivity analysis that is presented in the next section. However, this issue needs a comprehensive examination in another research.

Sensitivity analysis

In this section, a comprehensive sensitivity analysis has been performed according to the fundamental parameters of the proposed scheme and the results obtained from simulations and algorithm outputs discussed in the results section. Fault detection, fault type and phase identification, and fault location processes have been performed according to various parameters and conditions, such as adding the laterals to the studied system, changing the number of IEDs, the accuracy of the scenarios in different data transfer types (from PAs to CBs), the type of deep neural network structure used, etc. The results of this analysis are given in Tables 18 and 19. Also, the results deduced from the mentioned tables are shown in the form of graphics (Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16). As can be seen, changing any of the fundamental input parameters will cause a change in the accuracy of the algorithm output, which can be small or large, or even negligible in some cases. In the following, more details are described.

In this analysis, we have performed two investigations. first, the impact of different parameters on the proposed scheme performance of the scenarios examined in this study is investigated (Table 18) and then the impact of some important parameters is analyzed independently and on the structure of the eighth scenario (Table 19). The difference between these two studies is that in the first analysis (Table 18, Figs. 10, 11 and 12), the impact of other parameters is also considered, but in the second analysis (Table 19, Figs. 13, 14, 15 and 16), only the impact of the same parameter independently on the accuracy of the proposed scheme has been investigated. Although both analyses are in the same direction, the comparison of these two sensitivity analyses shows that the impact of some parameters when they are utilized with other parameters can increase or decrease compared to when they are utilized independently. For example, considering that in most cases the increase in the number of laterals without updating the DNNs has decreased the proposed scheme accuracy. Also, as can be seen in Table 18 and Fig. 12, in most scenarios, by changing the type of data transfer, the accuracy has increased or decreased, but the type of data transfer from PAs to CBs does not have any impact on the output accuracy and the mentioned increase or decrease in accuracy is caused by the effect of other parameters. However, in the second analysis which is shown in Figs. 13, 14, 15 and 16, in general and in most cases, the increase in the number of the laterals without updating the deep neural networks and in the constant conditions of the eighth scenario, has reduced the accuracy of the algorithm. However, in very few cases it has not been by the general trend. Meanwhile, the increase in the number of measurements has increased the accuracy of the proposed scheme. However, like the previous parameter, it was not by the general trend in very few cases. It should be noted that if the number of measurements and, as a result, the number of input parameters to the deep neural networks falls below a certain limit without changing the structure of the DNNs, the network may suffer from overfitting and the accuracy may not increase. The other results of the sensitivity analysis of the algorithm including measurements locations and how to use measurement data are presented in the related figures and tables. Tables 18 and 19 and Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16 show the results of the sensitivity analysis of the proposed scheme. Figures 10, 11 and 12 correspond to Table 18 and Figs. 13, 14, 15 and 16 correspond to Table 19. It is worth noting that, to provide a unified comparison between the fault detection accuracy and the fault location performance in the sensitivity analysis section, the fault location performance is defined as the complement of the error values (100-error%) in the related tables and figures.

The performance of the proposed scheme under specific conditions

In this subsection, the performance of the proposed scheme is evaluated under some specific fault and severe non-fault conditions. Fault conditions include external faults and faults in situations where only inverter-based sources supply the microgrid in the islanded operation mode, and severe non-fault conditions include some cases such as capacitor switching, measurement noise, varying DG penetration level, and changes in sampling frequency. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed scheme in the aforementioned specific cases, the proposed algorithm is investigated in two cases:

1- Examining the performance of the proposed scheme under conditions where deep neural networks are trained for similar conditions.

2- Examining the performance of the proposed scheme under conditions where deep neural networks are not trained for similar conditions.

Due to the better performance of the DNN type 2 compared to the DNN type 1, the proposed DNN type 2 is selected for investigating in this subsection. Also, the specific cases mentioned have been examined in the eight scenario structure. The results are given in Table 20. To assess the effectiveness of the proposed approach, an index known as the correct decision-making rate (CDR) index is employed, defined as follows.

Where,

TP (True Positive): The number of correctly detected fault events,

TN (True Negative): The number of correctly identified non-fault events,

FP (False Positive): The number of non-fault events incorrectly classified as faults (false alarms),

FN (False Negative): The number of fault events incorrectly classified as non-faults (missed faults).

Based on the results in Table 20, the proposed scheme demonstrates good accuracy in distinguishing specific fault and non-fault conditions, regardless of whether the proposed DNNs have been trained on similar conditions. However, its performance improves when the DNNs are trained on similar conditions. Additionally, the accuracy of fault detection increases with higher sampling frequencies. Nevertheless, the accuracy remains satisfactory even at sampling frequency of 1.2 kHz. It is worth noting that the data used in the proposed scheme was collected at a sampling frequency of 3.2 kHz. Furthermore, in conditions where the studied microgrid operates in islanded mode, with only inverter-based distributed resources (such as a PV, a BESS, or both) present in the circuit, the proposed scheme effectively detects faults with high accuracy under both trained and untrained conditions for similar conditions. However, the accuracy of the proposed scheme is higher when the DNNs are trained for similar conditions.

On the other hand, the pre-fault and fault currents at different protective agent (PA) locations for Scenario 1 are presented in Table 21. While similar information can also be provided for other scenarios, due to the large number of cases and to avoid excessive tables and content, Scenario 1 has been selected as a representative example. In this table, the maximum values of pre-fault and fault currents obtained from EMT simulations are reported when the microgrid is operating in the islanded mode. As can be observed, due to the presence of inverter-based distributed generations, the fault currents in some cases are close to the line currents in the normal operation, which creates a significant challenge for conventional protection schemes to reliably detect faults. However, according to the results, the proposed fault classification scheme can detect and locate various types of faults in different operation modes with appropriate accuracy.

Research requirements and comparison

Simulation process information and specifications of the system used

In this section, we describe the process of the simulations and analyses of the protective-based fault classification scheme using IEDs and hybrid DNNs in the studied microgrid. It involves the use of three different software and programming language tools. DIgSILENT Power Factory 15.1 software is used to simulate the CERTS microgrid and apply different fault and non-fault cases using DIgSILENT Programming Language (DPL) as a part of the software. DWT toolbox of MATLAB software is used to extract features from approximate and detailed coefficients of discrete wavelet transforms. Finally, the design, creation, training, and evaluation of the DNNs are performed using the Python 3.8 programming language on the TensorFlow platform and the Keras library. To obtain the results presented in this paper, in the first stage, we first defined a large number of fault and non-fault cases (presented in Tables 3 and 4) and then applied them to the studied network in DIgSILENT Power Factory software. Considering that it is not possible to apply this number of faults and non-fault cases manually, for this purpose, we took help from the programming environment of DIgSILENT software (DPL). So, by writing a code in DPL in which the graphic environment can be controlled, automatically and by using short circuit and load flow calculation of all events on the CERTS microgrid and the expected output parameters from the simulations including currents of phases A, B, and C and current sequence components were saved in different conditions and categorized on Excel files that were defined in advance. The Excel files that contained the output parameters from the simulation of events were transferred to MATLAB software to perform pre-processing steps, apply DWT, and extract statistical features from DWT coefficients. At this stage (the second stage), various processes were performed on the data so that they are ready to enter the next stage, which is the training of the deep neural networks using these data. The output of the data processing and features extraction processes in MATLAB software were stored in other Excel files in a categorized form and prepared for use in Python. In the third stage, deep neural network structures were designed and created in two different types including single and hybrid types in Python (TensorFlow platform and Keras library). The specifications and features of these structures are given in Table 6. Using the classified data at the end of the second stage, DNN structures were trained using the supervised learning method, and the training process was evaluated by evaluation parameters. In this process, 30% of the training data was used for the evaluation process. For each of the scenarios defined in this paper, the mentioned three stages were carried out, and the results and investigations were carried out in the previous sections. Table 22 lists some important information in the simulation and analysis process of the proposed algorithm and specifications of the system used.

The implementation requirements

The implementation of the proposed scheme of this paper includes several steps, the details of which are shown in Fig. 17. First, a post-training process must be applied to the trained DNNs. The purpose of this work is to reduce the response time of the DNNs in real-time conditions. This process includes removing parameters with low impact in the decision-making process of the deep neural networks and quantifying the DNNs parameters, which leads to an increase in the speed and accuracy of the DNNs compared to the network before this process. To implement the DNNs of the algorithm in hardware, the hardware to implement it should be selected correctly and according to its application in different parts of power systems. There are various options for this, including CPU, GPU, and programmable boards such as FPGAs. The OpenVino tool developed by Intel can be used to optimize and implement artificial intelligence tools on the CPU. Another tool called TensorRT was developed by Nvidia for implementation on GPU. Also, some companies have developed tools to implement artificial intelligence tools, including deep neural networks, on FPGAs, and OpenCL is one of these tools introduced by Intel for implementation on boards such as Terasic DE10-nano.

Trained deep neural networks can be implemented on any of the mentioned electronic equipment, of course, each has its details and complications. Before implementation, the parameters measured by the measurements must be properly provided to the trained DNNs and its protection requirements must be met. Each of the tools used for implementation must be evaluated and the correctness of their operation confirmed under different conditions. The trained DNNs implemented in electronic devices can be an alternative to protective relays with extensive capabilities. Considering that in power systems, the speed of fault detection is much more important and a priority than fault location, these considerations should be taken into account in the integration of deep neural networks in fault classification. In addition to the process of implementing deep neural networks on the aforementioned hardware, to implement the proposed scheme on real networks, there is a need to have laboratories equipped with dSPACE and OPAL-RT technologies to be able to use different system elements such as distributed energy resources, transmission lines and laterals, loads and other network equipment.

Comparison of the proposed scheme with State-of-the-art

As mentioned in the introduction section, many research studies in the state-of-the-art have been presented for all types of networks, such as distribution networks and AC and DC microgrids. In this section, the proposed scheme is compared with other schemes in different parts and aspects that are listed in Table 23. In this table, the eighth scenario performance in eight indices is considered for comparison of the proposed scheme with other research studies. In the proposed scheme, in addition to the mentioned parameters in the table, other parameters including microgrid configuration, load changing, location of faults, topology change, etc. are considered in the fault classification process.

Conclusions

Considering the challenges in microgrids’ fault detection and location issues, a PAs-based fault classification scheme using IEDs, discrete wavelet transforms, and two types of deep neural networks structures was presented in this paper. Eight protection scenarios based on overcurrent protection, with and without communication, were investigated. Finally, this paper provided a novel investigation of the impact of different parameters on the FDL scheme’s performance. The analysis of the impact of four crucial parameters on the accuracy of these schemes, namely adding laterals to the microgrid, adding IEDs and measurements to the protection plan, improving the structure of deep neural networks (hybrid structure), and data transfer type, was another significant contribution. Three main software and programming languages, namely DIgSILENT Power Factory, MATLAB, and Python, were utilized for the simulation of the proposed scheme and the acquisition of accurate results. The results demonstrate that the average accuracy for the eighth scenario in three parts including fault detection, fault type and phase identification, and fault location for DNN type-2 is 99.895%, 99.79%, and 98.425%, respectively. Also, adding the number of measurements and using the combination of different types of layers of the deep neural networks increases the output accuracy of the proposed algorithm in a general trend. On the other hand, adding laterals and reducing the number of measurements will reduce the accuracy of the algorithm output in a general trend (General trend: In most of the cases). Also, except in the scenarios of increasing laterals, increasing the variety of input data has increased the accuracy of the output. Increasing input data can increase or decrease the accuracy of the proposed algorithm depending on the type of structure and layers used in the deep neural networks. Another important result is that in all scenarios, the accuracy of DNN-2 was higher than DNN-1 due to the use of hybrid DNNs with two types of layers (Dense and GRU). One of the other important investigations carried out in this paper is to analyze the sensitivity of the algorithm output to different parameters. The results of the sensitivity analysis showed that different parameters may affect the accuracy of the algorithm while some others may not have much impact on the output and also some parameters can reduce or increase each other’s impact. However, considering that the lowest and highest accuracy of the proposed algorithm in the fault detection section is 95.54% and 99.96% respectively, in the fault type and phase detection section, is 95.56% and 99.86%, respectively, and in the fault location section is 93.49% and 98.73% respectively, so these accuracies are very suitable accuracies for the proposed scheme.

Among the suggestions that can be made for future work are working on the detection and classification of series faults, high-impedance faults, and also investigating solutions to increase resilience and robustness against cyber-attacks and communication failures in communications-based schemes.

Data availability

Data available on reasonable request from the authors. In this regard, Saman Esmaeilbeigi should be contacted as one of the authors.

References

Justo, J. J., Mwasilu, F., Lee, J. & Jung, J. W. AC-microgrids versus DC-microgrids with distributed energy resources: A review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 24, 387–405 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.067

Mahat, P., Chen, Z., Bak-Jensen, B. & Bak, C. L. A Simple Adaptive Overcurrent Protection of Distribution Systems With Distributed Generation, IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2 (3), 428–437, (2011). https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2011.2149550

Ustun, T. S., Ozansoy, C. & Zayegh, A. Modeling of a Centralized Microgrid Protection System and Distributed Energy Resources According to IEC 61850-7-420, IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 27 (3), 1560–1567, Aug. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrs.2012.2185072

Islam, M. R. & Gabbar, H. A. Study of micro grid safety & protection strategies with control system infrastructures. Smart Grid Renew. Energy. 3 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4236/sgre.2012.31001 (2012).

Ustun, T. S., Ozansoy, C. & Zayegh, A. Differential protection of microgrids with central protection unit support, in IEEE 2013 Tencon - Spring, IEEE, Accessed: 08, 2025. [Online]. (2013). Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/tenconspring.2013.6584408

Ebrahimpour, M., Vahidi, B. & Hosseinian, S. H. A hybrid superconducting fault current controller for DG networks and microgrids. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 23 (5), 5604306–5604306. https://doi.org/10.1109/tasc.2013.2267776 (2013).

Najy, W. K. A., Zeineldin, H. H. & Woon, W. L. Optimal protection coordination for microgrids with Grid-Connected and islanded capability. IEEE Trans. Industr. Electron. 60 (4), 1668–1677. https://doi.org/10.1109/tie.2012.2192893 (2013).

Kar, S. & Samantaray, S. R. Time-frequency transform‐based differential scheme for microgrid protection. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 8 (2), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2013.0180 (2014).

Casagrande, E., Woon, W. L., Zeineldin, H. H. & Svetinovic, D. A differential sequence component protection scheme for microgrids with Inverter-Based distributed generators. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 5 (1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2013.2251017 (2014).

Beder, H., Mohandes, B., Moursi, M. S. E., Badran, E. A. & Saadawi, M. M. E. A new Communication-Free dual setting protection coordination of microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 36 (4), 2446–2458. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2020.3041753 (2021).

Saleh, K., Allam, M. A. & Mehrizi-Sani, A. Protection of Inverter-Based islanded microgrids via synthetic harmonic current pattern injection. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 36 (4), 2434–2445. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2020.2994558 (2021).

Wong, J. Y. R., Tan, C., Bakar, A. H. A. & Che, H. S. Selectivity problem in adaptive overcurrent protection for microgrid with Inverter-Based distributed generators (IBDG): theoretical investigation and HIL verification. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 37 (4), 3313–3324. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2021.3126897 (2022).

Aazami, R., Esmaeilbeigi, S., Valizadeh, M. & Javadi, M. S. Novel intelligent multi-agents system for hybrid adaptive protection of micro-grid. Sustainable Energy Grids Networks. 30, 100682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.segan.2022.100682 (2022).

Borghetti, M., Bosetti, C. A., Nucci, M., Paolone & Abur, A. Integrated use of Time-Frequency wavelet decompositions for fault location in distribution networks: theory and experimental validation. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 25 (4), 3139–3146. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2010.2046655 (2010).

Pasdar, M., Sozer, Y. & Husain, I. Detecting and locating faulty nodes in smart grids based on high frequency signal injection. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 4 (2), 1067–1075. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2012.2221148 (2013).

Parikh, P., Voloh, I. & Mahony, M. Distributed fault detection, isolation, and restoration (FDIR) technique for smart distribution system, in 66th Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers, IEEE, 2013, 172–176. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available:, IEEE, 2013, 172–176. Accessed: 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/cpre.2013.6822035

Jiang, H., Zhang, J. J., Gao, W. & Wu, Z. Fault Detection, Identification, and location in smart grid based on Data-Driven computational methods. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 5 (6), 2947–2956. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2014.2330624 (2014).

Milioudis, N., Andreou, G. T. & Labridis, D. P. Detection and location of high impedance faults in multiconductor overhead distribution lines using power line communication devices. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 6 (2), 894–902. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2014.2365855 (2015).

Wang, J., Geng & Dong, X. High-Impedance fault detection based on nonlinear Voltage–Current characteristic profile identification. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 9 (4), 3783–3791. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2016.2642988 (2018).

Mishra, P., Samantaray, S. R. & Joos, G. Wavelet and Data-Mining based intelligent protection scheme for microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 7 (5), 2295–2304. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2015.2487501 (2016).

Mahfouz, M. M. A. & El-Sayed, M. A. H. Smart grid fault detection and classification with multi‐distributed generation based on current signals approach. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 10 (16), 4040–4047. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2016.0364 (2016).

Abdelgayed, T. S., Morsi, W. G. & Sidhu, T. S. A new approach for fault classification in microgrids using optimal wavelet functions matching pursuit. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 9 (5), 4838–4846. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2017.2672881 (2018).

Lala, H., Karmakar, S. & Ganguly, S. Detection and localization of faults in smart hybrid distributed generation systems: A Stockwell transform and artificial neural network-based approach. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 29 (2), e2725. https://doi.org/10.1002/etep.2725 (2018).

Yu, J. J. Q., Hou, Y., Lam, A. Y. S. & Li, V. O. K. Intelligent fault detection scheme for microgrids with Wavelet-Based deep neural networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 10 (2), 1694–1703. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2017.2776310 (2019).

Esmaeilbeigi, S. & Karegar, H. K. Intelligent Fault Detection and Location Scheme for Low Voltage Microgrids based on Recurrent and Radial Basis Function Neural Networks, in 28th Iranian Conference on Electrical Engineering (ICEE), IEEE, 2020, 1–6. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available:, IEEE, 2020, 1–6. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/icee50131.2020.9260904

Wang, Y., Chen, Q., Zeng, X., Huang, X. & Song, Q. Faulty feeder detection based on space relative distance for compensated distribution network with IIDG injections. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 36 (4), 2459–2466. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2020.3004810 (2021).

Wei, X. et al. Faulty feeder detection for Single-Phase-to-Ground fault in distribution networks based on transient energy and cosine similarity. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 37 (5), 3968–3979. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2022.3142186 (2022).

Jalalt, S. M., Miralizadeh, S., Talavat, V. & Boalndi, T. G. A novel superimposed voltage energy-based approach for single phase to ground fault detection and location in distribution networks. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 17 (18), 4215–4233. https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.12981 (2023).

Gupta, R. K., Pachar, O. P., Mahela & Khan, B. Fault Detection and Classification to Design a Protection Scheme for Utility Grid with High Penetration of Wind and Solar Energy, International Journal of Energy Research, 1–16, 2023, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4418741

Bhagwat, S., Dutta, V. K., Jadoun, A. S., Veerendra & Sahu, S. K. A customised artificial neural network for power distribution system fault detection. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18 (11), 2105–2118. https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.13186 (2024).

Su, X. et al. Kernel-PCA‐based single‐phase Earth fault detection model using multilayer perceptron in deep learning. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18 (4), 834–843. https://doi.org/10.1049/gtd2.13117 (2024).

Najar, H., Kazemi Karegar & Esmaeilbeigi, S. Multi-agent protection scheme for microgrid using deep learning. IET Renew. Power Gener. 18 (4), 663–678. https://doi.org/10.1049/rpg2.12929 (2024).

Mishra, D. P., Samantaray, S. R. & Joos, G. Wavelet and Data-Mining based intelligent protection scheme for microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid. 7 (5), 2295–2304. https://doi.org/10.1109/tsg.2015.2487501 (2016).

Kar, S., Samantaray, S. R. & Zadeh, M. D. Data-Mining model based intelligent differential microgrid protection scheme. IEEE Syst. J. 11 (2), 1161–1169. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsyst.2014.2380432 (2017).

Mishra, M. & Rout, P. K. Detection and classification of micro-grid faults based on HHT and machine learning techniques. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 12 (2), 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-gtd.2017.0502 (2017).

Alexopoulos, T., Biswal, M., Brahma, S. M. & Khatib, M. E. Detection of fault using local measurements at inverter interfaced distributed energy resources, in 2017 IEEE Manchester PowerTech, IEEE, Jun. 1–6. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. (2017). Available: https://doi.org/10.1109/ptc.2017.7981089

Cepeda et al., “Intelligent Fault Detection System for Microgrids,” Energies, 13 (5), 1223, 2020, doi: 10.3390/en13051223.

Hadi Abdulwahid and S. Wang, “A Novel Approach for Microgrid Protection Based upon Combined ANFIS and Hilbert Space-Based Power Setting,” Energies, 9 (12), 1042, 2016, doi: 10.3390/en9121042.

Esmaeilbeigi, S., Karegar, H. K. & Shafie-khah, M. A multi-layer protection scheme for active distribution networks integrated with AC and DC microgrids. Electr. Eng. 107 (8), 9987–10020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-025-03011-z (2025).

Lasseter, R. H. et al. CERTS microgrid laboratory test bed. IEEE Trans. Power Delivery. 26 (1), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpwrd.2010.2051819 (2011).

Najar, H. K., Karegar & Esmaeilbeigi, S. Intelligent Islanding Detection Scheme for Microgrid Based on Deep Learning and Wavelet Transform, in 10th Smart Grid Conference (SGC), IEEE, 2020, 1–5. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available:, IEEE, 2020, 1–5. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/sgc52076.2020.9335761

Sharif, A. A., Karegar, H. K. & Esmaeilbeigi, S. Fault detection and location in DC microgrids by recurrent neural networks and decision tree classifier. Energy Eng. Manage. 11 (4), 40–47 (2023).

Sharif, A., Karegar, H. K. & Beigi, S. E. Fault Detection and Location in Ring DC Micro-grid by Radial Basis Function Neural Network and SVM Classifier, in 13th Smart Grid Conference (SGC), IEEE, 2023, 1–5. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available:, IEEE, 2023, 1–5. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/sgc61621.2023.10459298

Sharif, A., Karegar, H. K. & Beigi, S. E. Intelligent Fault Detection and Location Method for DC Micro-Grid by Considering Different Fault and Non-Fault Operation Modes, in 13th Smart Grid Conference (SGC), IEEE, 2023, 1–7. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available:, IEEE, 2023, 1–7. Accessed: Sep. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/sgc61621.2023.10459315

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Saman Esmaeilbeigi wrote the main manuscript text and all authors reviewed the manuscript. Other contributions of the authors are listed below.Saman Esmaeilbeigi: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, validation, software, writing, review, and editing. Hossein Kazemi Karegar: Project administrator, supervision, conceptualization, investigation, writing, review, and editing. Abolfazl Najar: Formal analysis, data curation, software, validation, writing, review, and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Esmaeilbeigi, S., Kazemi Karegar, H. & Najar, A. A fault classification scheme based on protective agents for microgrid with parameters impact analysis. Sci Rep 15, 44316 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28178-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-28178-0