Abstract

Piezoelectric microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) mirrors enable precise and rapid beam steering with low power consumption, making them essential components in light detection and ranging (LiDAR) and advanced optical imaging systems. Lead zirconate titanate (PZT) offers a high piezoelectric coefficient suitable for such applications. However, its elevated processing temperatures (typically 500 °C–700 °C), lead content that raises contamination concerns during complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) integration, and hysteresis-induced nonlinearity limit its broader integration into MEMS mirrors. In contrast, aluminum nitride (AlN), with low deposition temperatures (below 400 °C) and contamination-free composition, offers CMOS compatibility, environmental stability, and low hysteresis, making it a promising lead-free alternative. However, its intrinsically low piezoelectric coefficient limits actuation efficiency for large scan angles. To overcome this limitation, scandium (Sc) doping has emerged as an effective strategy to enhance the piezoelectric response of AlN. Sc-doped AlN (AlScN) enables relatively large scan angles in MEMS mirror applications due to its significantly enhanced piezoelectric coefficients and reduced mechanical stiffness, while retaining essential advantages, such as CMOS compatibility and environmental robustness. This review comprehensively examines the recent progress in AlN and AlScN for MEMS mirror applications. We focus on its impact on piezoelectric properties, fabrication techniques, and mirror performance. Furthermore, we provide a comparative assessment of AlN- and AlScN-based MEMS mirrors, highlighting their respective advantages, limitations, and application potentials. Finally, this review summarizes recent developments and research trends, providing insights into their performance benefits and directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) mirrors are widely utilized in advanced optical systems and imaging applications, including display projectors1,2, optical switches3,4, optical coherence tomography5,6, head-up displays7,8, and smart headlights9. In light detection and ranging (LiDAR) systems10,11, MEMS mirrors enable high-speed beam steering, which is essential for achieving high-resolution 3D mapping and real-time environmental perception in autonomous vehicles and advanced driver-assistance systems12. Among various actuation mechanisms explored for MEMS mirrors, including electrostatic, electromagnetic, and electrothermal approaches13,14, piezoelectric actuation has emerged as particularly advantageous due to its balance of precision, speed, and energy efficiency15,16. Electrostatic actuators enable high-speed operation with low power consumption but suffer from inherently limited deflection angles and require high driving voltages, complicating driver electronics and increasing system complexity. Electromagnetic actuators achieve larger scan angles but necessitate bulky magnetic components, limiting miniaturization and increasing power demands. Electrothermal actuators offer large displacements but exhibit slow response times and excessive power consumption, making them unsuitable for high-speed scanning applications. In contrast, piezoelectric actuation delivers precise angular control, fast response times, and low steady-state power consumption at moderate driving voltages, addressing the key challenges in compact, energy-efficient MEMS mirror design17.

The most commonly used piezoelectric materials in MEMS devices are lead zirconate titanate (PZT). PZT, with its high piezoelectric coefficient (d₃₃ = 200–600 pC/N), enables large displacement generation, making it widely used in resonators and MEMS mirrors18,19,20,21,22. However, despite its excellent piezoelectric characteristics, PZT presents significant fabrication and operational challenges that limit its practical use in MEMS applications. One major limitation of PZT is its high-temperature processing requirements. Deposition typically necessitates sol-gel crystallization at 500 °C–700 °C or sputtering deposition followed by annealing at 600 °C–700 °C to form the perovskite crystal structure. These processing temperatures are often incompatible with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) processes, particularly in back-end-of-line integration, here thermal budgets are tightly constrained23,24. In alternative workflows, where MEMS fabrication is performed prior to CMOS processing, high-temperature treatment can be accommodated25. However, the integration of Pb-containing PZT into standard CMOS workflows raises contamination risks26,27. Pb can diffuse into gate dielectrics, contaminate cleanroom tools, and degrade the electrical reliability of surrounding devices. Consequently, its use typically necessitates dedicated toolsets, sealed deposition chambers, or full process isolation from logic wafers. Moreover, PZT’s ferroelectric nature introduces residual polarization and nonlinear hysteresis, which can lead to signal distortion and reduced angular precision in repetitive beam steering operations28. As a result, while PZT-based MEMS mirrors have been extensively demonstrated, they inherently suffer from hysteresis-induced nonlinearity, long-term stability concerns, and integration difficulties with standard CMOS processes, necessitating alternative piezoelectric materials for MEMS mirror applications.

In contrast, aluminum nitride (AlN) has a lower piezoelectric coefficient than PZT, limiting its actuation efficiency. However, AlN offers several advantages that make it an attractive material for MEMS mirrors29. Its low-temperature deposition (<400 °C) enables integration with CMOS processes without degrading metal interconnects or semiconductor layers30. Unlike PZT, AlN naturally forms a wurtzite crystal structure during sputtering, exhibiting intrinsic piezoelectric properties without the need for additional polarization treatments31,32. Furthermore, AlN is non-ferroelectric, avoiding hysteresis-related instability in repetitive actuation33, and its Pb-free composition ensures compliance with environmental regulations. Despite these benefits, AlN’s intrinsically low piezoelectric response continues to limit its performance in MEMS mirror applications that require large scan angles. To address this, researchers have investigated metal ion doping strategies to enhance AlN’s piezoelectric properties. Among various dopants—such as chromium34, yttrium35,36, tantalum37, and magnesium38—scandium (Sc)39,40 has demonstrated the most significant improvements. Sc doping induces lattice distortion and increases ionicity in the AlN crystal lattice, resulting in enhanced spontaneous polarization and a stronger internal electric field. These effects collectively lead to a substantial increase in the piezoelectric coefficient. For example, doping AlN with 40% Sc has been shown to increase its piezoelectric coefficient by approximately 500%39. Sc-doped AlN (AlScN) builds upon the key advantages of AlN—including CMOS compatibility, thermal stability, and low-temperature processability—while significantly enhancing piezoelectric performance41,42. This makes AlScN particularly attractive for MEMS mirror applications requiring higher actuation efficiency, precise beam steering, and long-term operational stability.

Given these advantages, this review systematically examines recent advances in AlN- and AlScN-based MEMS micromirrors, focusing on piezoelectric properties, fabrication methods, and device performance. Figure 1 provides a structural classification of representative MEMS mirror designs based on the two materials, categorized by degrees of freedom in AlN-based devices and by fabrication architecture in AlScN-based ones. To enable direct comparisons, we also outline key performance metrics, such as scanning mode, resonant frequency, optical scan angle, and mirror plate size, which are used consistently throughout the review. This review compares the structural and performance characteristics of these two material systems, highlighting their respective strengths, trade-offs, and future development potential.

The upper section categorizes devices according to structural configuration: AlN-based mirrors are grouped by degrees of freedom (1-DOF103 and 2-DOF108), while AlScN-based designs are classified by fabrication architecture (three-level60 and single-layer constructions121). The lower section outlines key performance metrics, such as scanning mode, resonant frequency, optical scan angle, and mirror plate size, which serve as comparative benchmarks throughout this review

Properties of AlScN thin films and their impact on MEMS micromirror performance

Enhancing the piezoelectric response of AlN has been a key strategy for improving actuation efficiency in MEMS mirrors, particularly for achieving large scan angles. Traditional approaches, such as optimizing the c-axis orientation through the use of seed layers (e.g., platinum43, molybdenum44,45, titanium46,47,48,49) and adjusting sputtering conditions50,51,52, have improved film texture and structural integrity. However, these methods offer limited enhancement to the intrinsic piezoelectric coefficient of AlN, which constrains their effectiveness in MEMS mirror applications requiring higher torque generation or larger angular displacements.

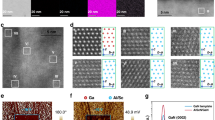

In contrast, substitutional doping of AlN with Sc provides a more direct and effective means of enhancing piezoelectric performance. Among various metal dopants, Sc demonstrates the most significant improvement due to its ability to induce lattice distortion and increase ionicity39,40. Sc exhibits the lowest formation energy (0.3 eV) among various metal dopants when substituting for aluminum, enabling stable doping at high concentrations without causing significant lattice instability53,54. Akiyama et al.39,40 first reported a substantial enhancement of the piezoelectric coefficient (d₃₃) in AlScN thin films, achieving values of 27.6 pC/N at 43% Sc concentration under CMOS-compatible deposition conditions (400 °C). Subsequent work by Olaf Zywitzki et al.55 systematically characterized AlScN films across Sc concentrations from 0 to 57%. As shown in Fig. 2a, the piezoelectric coefficient (d33) increases from 8.4 pC/N for undoped AlN to 23.6 pC/N at 33.2% Sc concentration, with a saturation observed between 35 and 43%. This enhancement directly translates to improved actuation efficiency in MEMS mirrors, enabling larger angular deflections. However, the benefits of Sc doping come with trade-offs. As illustrated in Fig. 2b, c, increasing Sc content reduces the mechanical robustness of AlScN films. Hardness declines from 23 to 13.5 GPa, and Young’s modulus decreases from 338 to 193 GPa as Sc concentration rises to approximately 43%. This softening effect, driven by the longer and more ionic Sc-N bonds compared to Al-N bonds, facilitates greater strain but may compromise mechanical stability in MEMS mirrors, particularly in high-frequency resonant or long-term quasi-static applications where fatigue could be a concern. At Sc concentrations above 51%, a sharp decline in piezoelectric response occurs, attributed to a phase transition from the wurtzite to the rock-salt structure56. As shown in Fig. 2d, this transition eliminates the non-centrosymmetric crystal structure essential for piezoelectricity, thereby capping the effective doping range for high-performance AlScN thin films used in MEMS mirrors.

Effect of Sc concentration on a the piezoelectric coefficient (d33), b hardness, and c Young’s modulus of AlScN layers55. d For Sc concentrations above x = 0.40, Al1−xScxN exhibits a coexistence of wurtzite (AlN) and rock-salt (ScN) phases. As the Sc content increases beyond x = 0.56, the material undergoes a structural transition, favoring the rock-salt phase as the dominant crystalline structure56. e Polarization–electric field loops for Al1−xScxN (x = 0.27–0.43) and PZT 52/48, showing composition-dependent ferroelectricity57. f Polarization, coercive field, and maximum applicable electric field as functions of Sc concentration57,58

Additionally, Fig. 2e presents the polarization hysteresis loops that reveal distinct ferroelectric switching behavior in AlScN for Sc concentrations between 27 and 43%, with decreasing remnant polarization (Pr) and loop area as the Sc concentration increases. This behavior was demonstrated by Fichtner et al.57, who fabricated polycrystalline AlScN films (thickness: 400, 600, 1000 nm) via reactive sputtering on Si substrates covered with an AlN/Pt bottom electrode at 400 °C. Notably, as shown in Fig. 2f, the coercive field (Ec) remains high across this composition range—exceeding 1.5 MV/cm57,58—indicating that polarization reversal in AlScN requires a significantly stronger electric field than in PZT (0.03–0.12 MV/cm)59. Consequently, under typical low-voltage driving conditions (e.g., ±200 V) considering thin film thickness, AlScN actuators exhibit hysteresis-free mechanical behavior, which makes AlScN particularly suitable for MEMS mirror applications60.

While increasing the Sc concentration up to the wurtzite-to-rock-salt transition point enhances the piezoelectric response by introducing greater lattice distortion and ionicity, it also tends to reduce the breakdown field due to increased defect density and structural instability. Tsai et al.61 reported a breakdown field of 6.5 MV/cm with a standard deviation of 1.0 MV/cm for a 50 nm-thick Al0.78Sc0.22N film deposited at room temperature. The film also exhibited a remnant polarization of 70 μC/cm² and a coercive field of 5.8 MV/cm. Similarly, Zheng et al.62 investigated the breakdown behavior of 45 nm-thick AlScN films and reported that single-layer Al0.72Sc0.28N and Al0.64Sc0.36N exhibited breakdown fields of 5.99 and 5.86 MV/cm, with breakdown-to-coercive field ratios of 1.37 and 1.26, respectively. While the reduction in dielectric strength with increasing Sc concentration can limit the applicable voltage in quasi-static MEMS actuators, moderate Sc levels (e.g., 22–28%) have been shown to achieve an optimal trade-off between enhanced piezoelectric response and electrical reliability.

To mitigate the reduction in breakdown field associated with increasing Sc concentration, multilayer structuring of AlScN has emerged as a promising strategy. Zheng et al.62 systematically investigated the effects of multilayer structuring on electrical breakdown by fabricating multilayer stacks composed of alternating Al0.72Sc0.28N and Al0.64Sc0.36N layers, while keeping the total thickness and volume constant. As shown in Fig. 3a, cross-sectional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging confirmed well-defined internal interfaces, further characterized by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping and line scan (Fig. 3b). Schematic layouts of the three-, five-, and seven-layer configurations are shown in Fig. 3c. As depicted in Fig. 3d, the breakdown field increases from approximately 5.9 MV/cm in single-layer films to 7.2 MV/cm in the seven-layer structure, while maintaining stable remnant polarization. This improvement is attributed to dielectric strengthening induced by internal interfaces, which disrupts the vertical propagation of electrical trees. Such enhancements enable wider voltage operating windows and improved reliability, which are key requirements for MEMS actuators that demand both high breakdown tolerance and strong piezoelectric response.

a Cross-sectional TEM image of the five-layer AlScN film62. White dashed lines indicate internal interfaces between sublayers. b EDS mapping and line scan of the boxed region in a, showing Sc compositional variation across the multilayer stack62. c Schematic of three-, five-, and seven-layer configurations composed of alternating Al0.72Sc0.28N and Al0.64Sc0.36N sublayers62. d Weibull plots of breakdown strength measured with 10 kHz triangular DC pulses, comparing single- and multilayer samples62. e Side-view SEM image of a 2 × 500 nm Al0.7Sc0.3N double-layer, with polarization directions after ferroelectric switching63. f Effective longitudinal piezoelectric coefficient (d33,f) of 500 nm-thick Al1-xScxN films with varying Sc content, comparing single-layer (sl) and double-layer (dl) structures64. g Strain–electric field responses of PZT, AlN, and AlScN in single- and double-layer formats, demonstrating enhanced strain in double-layer configurations64

In the context of MEMS actuators requiring large displacements or high output forces, such multilayer AlScN architectures offer key advantages: extended operational voltage windows, enhanced breakdown reliability, and preservation of high piezoelectric response. Fichtner et al.63 proposed a double-layer ferroelectric Al0.7Sc0.3N actuator structure, demonstrating enhanced strain output while preserving linear and bipolar actuation characteristics, as shown in Fig. 3e. This architecture leverages the constructive contribution of strains from both layers, each with opposite polarization after switching. Expanding on this concept, Kreutzer et al.64 introduced a double-layer Al0.65Sc0.35N actuator with an inverted polarization in one layer. As shown in Fig. 3f, this configuration exhibits a higher effective longitudinal piezoelectric coefficient compared to single-layer counterparts. Notably, the resulting strain–electric field response, shown in Fig. 3g, demonstrates performance on par with PZT actuators, while requiring only about half the electric field to achieve comparable displacement. These results highlight the promise of double-layer AlScN structures in enabling energy-efficient, high-performance MEMS actuation through internal strain enhancement mechanisms and ferroelectric tuning.

While this review primarily focuses on PZT, AlN, and AlScN, Table 1 expands the comparison to include additional piezoelectric materials—such as potassium sodium niobate (KNN), lithium niobate (LiNbO3), and niobium-doped PZT (PNZT)—to enable a more comprehensive assessment of AlScN’s suitability for MEMS mirror applications. The comparison highlights four key design considerations for MEMS mirrors, such as piezoelectric coefficient, hysteresis behavior, CMOS compatibility, and Pb content.

PZT and PNZT offer the high piezoelectric coefficients (≈12.2–15.3 C/m²)65, but their low coercive fields (<0.12 MV/cm) make them prone to domain switching even under typical MEMS driving conditions, leading to hysteresis66. In addition, their high processing temperatures (500 °C–700 °C) and Pb content pose significant challenges for CMOS co-integration and raise environmental concerns. KNN eliminates the toxicity associated with Pb but still requires crystallization at ≥600 °C67,68, and its mobile K⁺/Na⁺ ions pose a contamination risk in CMOS cleanroom environments. Furthermore, due to its ferroelectric nature and coercive fields, KNN exhibits mechanical hysteresis in its electromechanical response69. LiNbO3 offers various piezoelectric coefficients depending on the crystal cut angle and enables large optical deflection angles in MEMS mirrors, as demonstrated by 3D FEM simulations using COMSOL70. Despite its non-hysteretic piezoelectric behavior and Pb-free composition71, the fabrication of LiNbO₃ thin films typically requires complex processes, such as ion slicing72. Consequently, MEMS mirrors based on LiNbO3 thin films have rarely been reported73.

In contrast, AlN is a non-ferroelectric material that is fully CMOS-compatible and highly reliable; however, its low piezoelectric coefficient (≈1.1 C/m²) limits its effectiveness in MEMS mirrors requiring large optical angles60. AlScN bridges this performance gap. Scandium alloying significantly enhances the piezoelectric response (up to ≈ 3.2 C/m² at x ≈ 0.41) while maintaining a low-temperature, CMOS-friendly sputtering process (<400 °C). Crucially, Al1-xScxN exhibits composition-dependent electromechanical behavior: films with x ≤ 0.25 remain non-ferroelectric and exhibit linear, bidirectional actuation; above x ≈ 0.27, the films become switchable ferroelectrics, yet their coercive fields remain well above the electric fields typically applied in MEMS mirrors. As a result, even ferroelectric AlScN films operate in the sub-coercive regime, enabling linear and hysteresis-free actuation in practical use.

From a MEMS mirror design perspective, AlScN enables either lower actuation voltages or larger optical scan angles, depending on the specific design priorities and performance requirements of LiDAR and high-resolution optical systems. Nevertheless, optimizing Sc concentration is essential to balance piezoelectric gains with mechanical reliability. Excessive doping, while increasing the piezoelectric coefficient, may lead to structural vulnerabilities.

Fabrication of AlScN for MEMS mirrors

Achieving highly c-axis-oriented AlScN thin films is critical to maximizing the actuation efficiency and stability of piezoelectric MEMS mirrors. Poor crystalline alignment, particularly the formation of abnormally oriented grains (AOGs), degrades piezoelectric performance and compromises device reliability. Stephan Barth et al.74 emphasized that AOGs disrupt the uniformity of the wurtzite structure, reducing piezoelectric response and increasing defect density in MEMS devices. Recent studies on AlScN film deposition have been directed toward improving film texture, including efforts to enhance c-axis alignment and minimize AOGs. In parallel, various anisotropic dry etching techniques—such as inductively coupled plasma (ICP), ion beam etching (IBE), and reactive ion beam etching (RIBE)—have been explored for the precise patterning and reliable release of AlScN-based MEMS mirror structures.

Deposition of AlScN

AlScN films offer significant advantages in piezoelectric applications due to their enhanced piezoelectric coefficients. However, compared to pure AlN, their deposition demands more stringent process control, as several critical issues frequently arise during film growth75. First, oxygen ingress into the sputtering chamber, often caused by residual outgassing, can result in the formation of scandium oxide (Sc2O3) impurities, as scandium has a lower oxide formation enthalpy (−1908.8 kJ/mol) than aluminum (−1675.7 kJ/mol). These oxides disrupt film stoichiometry, induce lattice distortion, and promote nitrogen and metal vacancies, ultimately degrading piezoelectric performance76,77. In addition, AOGs are increasingly formed with higher Sc concentrations. AOGs nucleate at Sc-enriched grain boundaries and lead to surface roughening and degraded c-axis texture, thereby compromising film texture78. Furthermore, residual stress accumulated during deposition not only influences the actuation behavior of frequency-driven MEMS mirrors but also degrades the intrinsic piezoelectric properties of AlScN79. It alters physical characteristics, such as mechanical stability and may cause microcracks or delamination in severe cases. The stress becomes more pronounced at higher Sc concentrations, where increased Sc–N bond lengths and reduced bond angles lead to tetrahedral distortion and atomic disorder. Growth on lattice-mismatched substrates further exacerbates stress through defect accumulation77. These interrelated challenges, including oxygen-induced impurities, abnormal grain growth, and residual stress, underscore the importance of optimizing deposition conditions to achieve high crystal quality and stable device performance. We next review key deposition strategies that have been developed to enhance c-axis orientation in AlScN films.

Among deposition methods for AlScN—metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD), molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), and reactive magnetron sputtering—reactive sputtering has emerged as the most practical for MEMS mirrors due to its scalability, cost-effectiveness, and ability to control thin-film stress75,80. AlScN thin films can be deposited using a single sputtering target composed of an AlSc alloy with a fixed Al-to-Sc composition81. Alternatively, dual-target co-sputtering can be employed, where separate Al and Sc targets are installed in two sputtering guns and the Sc concentration is controlled by adjusting process parameters, such as the sputtering power75. Another approach involves the use of a double-ring target, in which the outer ring consists of Al and the inner ring of Sc, enabling composition tuning within a single sputtering gun82. Crystalline quality is commonly evaluated by the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of X-ray rocking curves. Optimized sputtering processes have achieved FWHM values below 2° for AlScN films with Sc concentrations between 6 and 30%, indicating excellent c-axis orientation suitable for MEMS mirror applications, as summarized in Table 2.

Valeriy Felmetsger et al.81 demonstrated that an AC-powered dual-cathode S-gun sputtering system, combined with optimized nitrogen (N₂) flow rates, significantly improved c-axis alignment in thick AlScN films (1–2 μm). Their two-step process—initial high N₂ flow for better orientation, followed by reduced flow for surface smoothness—produced films with both low roughness and high crystalline quality. Similarly, Yuan Lu et al.83 reported that increasing N₂ concentration in pulsed DC magnetron co-sputtering reduced misoriented grains and improved the piezoelectric coefficient. However, they noted that increased target-to-substrate distance degraded film quality, underscoring the need for precise control of deposition parameters. In summary, nitrogen flow rate, plasma conditions, and substrate positioning are important factors that influence the quality of AlScN thin films. Optimizing these and other deposition parameters contributes to achieving stable actuation, large angular displacements, and long-term reliability in MEMS mirrors.

Etching of AlScN thin films

Compared to pure AlN, the etching behavior of AlScN thin films is strongly influenced by the concentration of Sc incorporation. While AlN exhibits a relatively fast etch rate (≈13 nm/s with ICP84, 7 nm/s with ICP85), increasing the Sc concentration in AlScN films generally leads to reduced etch rates (≈ 1.3 nm/s with ICP84) and makes it more difficult to achieve vertical sidewalls in both dry and wet etching processes. Hardy et al.84 examined Cl2-based ICP etching of AlN, Al0.98Sc0.02N, and Al0.84Sc0.16N, observing a clear trend of decreasing etch rate with higher Sc content, as shown in Fig. 4a. This behavior is attributed to the increasing fraction of strong Sc–N bonds (bond dissociation energy ≈ 13.35 eV), which lowers the overall chemical reactivity in plasma, and the formation of low-volatility byproducts, such as ScCl3, which accumulate on the surface and hinder anisotropic etching84,86.

a Graph of ICP etch rate for pure AlN and AlScN films with varying Sc concentrations84. b Graph of KOH etch rate for AlScN films as a function of Sc concentration87. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of c the sidewall angle of an AlScN film etched by KOH, d the sidewall angle of an AlScN film etched by TMAH88, e residues remaining after TMAH etching, and f undercut observed after TMAH etching

Wet etching using potassium hydroxide (KOH) and tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH) exhibits a similar trend. Tang et al.87 reported that the vertical etch rate steadily declined with increasing Sc content up to 42% in KOH solution, as shown in Fig. 4b. In addition, the sidewall angle decreased from 56.7° at 12.5% Sc to 43.0° at 42% Sc (Fig. 4c), indicating a loss of anisotropy. Shifat et al.88 further confirmed that TMAH etching exhibited slower rates and slight degradation in sidewall angle, decreasing from 88.2° at 20% Sc to 87.3° at 40%, as shown in Fig. 4d. Moreover, etch residues and surface roughness were observed at higher Sc concentrations, attributed to the formation of poorly soluble Sc–O or Sc–OH compounds under alkaline conditions, as shown in Fig. 4e. In addition, significant undercutting was evident following the wet etching process, as shown in Fig. 4f. Although Sc incorporation enhances piezoelectric performance, these findings indicate a clear trade-off in etch performance and process compatibility. Careful consideration of Sc content is therefore essential in process design, particularly for applications requiring high aspect ratio patterning or vertical sidewalls.

Precise patterning of AlScN thin films is vital for defining MEMS mirror structures, such as torsional beams and gimbals. Wet etching methods—using KOH85,89, TMAH87,90, and hot phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄)64—are limited by their isotropic nature and poor scalability for high-precision MEMS fabrication91. As a result, dry etching techniques have become the standard for AlScN MEMS fabrication, offering superior anisotropy and better profile control. ICP etching84,85,86,92,93 and RIBE94 are particularly effective. RIBE has demonstrated excellent results in both etch rate and sidewall profile. R. James et al.94 explored both IBE and RIBE techniques for AlScN films. While IBE showed limited etch rates (17 nm/min), RIBE demonstrated improved performance, achieving an etch rate of approximately 36 nm/min. The RIBE process also resulted in profile angles ranging from 60° to 80°, with low surface roughness of less than 5 nm. ICP etching, commonly employing Cl₂/BCl₃/N₂ or BCl₃/Ar gas chemistries86,92, achieves high etch rates (230 nm/min with Cl₂/BCl₃/N₂, 79 nm/min with BCl₃/Ar) and steep sidewalls (84° with Cl₂/BCl₃/N₂). However, careful optimization of process parameters—such as ICP power, RF bias, and chamber pressure—is required to balance etch rate, sidewall verticality, and surface quality92,93. In summary, advanced dry etching techniques are critical for fabricating high-performance AlScN MEMS mirrors, enabling precise beam steering with high reliability and scalability.

AlN and AlScN-based MEMS micromirrors

Section 4 provides an overview of piezoelectric MEMS micromirrors based on AlN and AlScN thin films by introducing key studies that highlight their structural and performance features. We begin by describing the two main actuation modes, resonant and quasi-static operation, and discuss their impact on device behavior. AlN-based micromirrors are classified according to their degrees of freedom (DOF), including one and two-DOF designs. AlScN-based devices are organized by structural configuration, specifically three-level and single-layer architectures. To clarify the practical advantages of AlScN over AlN, we also summarize major experimental and simulation results that directly compare their performance. Lastly, we review demonstrated application domains and explore future opportunities enabled by the distinct properties of each material system.

MEMS micromirrors are evaluated based on key performance metrics, including optical scan angle and operating voltage. The mechanical tilting angle of piezoelectric MEMS micromirrors, which is translated into the optical scan angle, is generated by piezoelectric film actuation. This tilting behavior is fundamentally governed by the effective transverse piezoelectric coefficient e31,f, which integrates both the electrical and mechanical characteristics of the material. As described by Ouyang et al.95, this coefficient is defined as Eq. (1).

where \({d}_{31}\) is the in-plane piezoelectric constant, and \({s}_{11}^{E}\), \({s}_{12}^{E}\) are the in-plane elastic compliances under a constant electric field. Given that elastic compliance is the inverse of Young’s modulus, this equation clearly shows that the electromechanical force generated by the actuator, as represented by e31,f, increases with a higher \({d}_{31}\) and a lower Young’s modulus.

This relationship becomes especially relevant when considering the angle–voltage behavior in piezoelectric micromirrors96. As shown in the angle–voltage relationship in Eq. (2), the mirror tilting angle is proportional to the actuation force generated by the film, which in turn scales with e31,f. This actuation is further modulated by a structural factor, Γ, which accounts for the geometry and mechanical coupling between the actuator and the mirror.

Thus, materials with enhanced e31,f enable greater mechanical response at a given drive voltage, \({\rm{V}}\). In this context, AlScN exhibits both a significant increase in d31 and a reduction in elastic modulus compared to pure AlN55, resulting in a markedly higher e31,f97. As Boni et al.98 emphasized, this effective coefficient is the critical factor that determines the force transmitted from the piezoelectric film to the MEMS structure, and therefore directly influences the tilting angle. As a result, the improved performance of AlScN-based MEMS mirrors, especially the greater optical scan angle, can be attributed to the simultaneous enhancement in piezoelectric response and reduction in material stiffness. These enhancements are quantitatively captured in the definition and functional role of e31,f, making it the key material parameter for optimizing angular displacement in piezoelectric MEMS mirrors.

Piezoelectric MEMS micromirrors generally operate in either resonant or quasi-static mode. In resonant mode, actuation near the device’s resonant frequency enables efficient energy accumulation, resulting in large scanning angles even at relatively low driving voltages. This behavior is intrinsically associated with a high quality-factor (Q-factor), reflecting low energy dissipation and sustained oscillation. To maintain oscillation efficiency and prevent performance degradation over time, materials used in resonant-mode devices must exhibit low mechanical loss and high elastic stability. The resonant frequency of a micromirror is a critical design parameter, determined by the moment of inertia of the mirror plate and the stiffness of the suspension springs. Devices with lower resonant frequencies (<5 kHz) typically incorporate larger reflective areas and softer springs, resulting in lower Q-factors (<200) but offering a broader operational bandwidth—ideal for applications requiring wide-frequency response. Conversely, high-frequency designs (>20 kHz) use smaller mirrors and stiffer suspensions to achieve higher Q-factors (>800), albeit with a narrower bandwidth. This inherent trade-off between Q-factor and bandwidth is a central consideration in the design of resonant micromirrors for specific performance requirements99.

In contrast, quasi-static operation offers direct control over angular position through linear voltage-displacement relationships. This mode is better suited for applications requiring high linearity, responsiveness to arbitrary waveforms, and closed-loop control. However, achieving large deflection angles often demands higher actuation voltages, making materials with strong dielectric strength particularly advantageous. In this quasi-static mode, the dielectric breakdown field and long-term reliability of the piezoelectric material under DC bias become critical design considerations. Additionally, low leakage current and stable permittivity are important to ensure accurate control and minimize power loss.

AlN-based MEMS micromirrors

AlN has emerged as a promising piezoelectric material for MEMS micromirrors. The first AlN-based MEMS micromirror was fabricated by Shao et al.100 in 2018. Their device featured 1-DOF motion with both piston and tilting capabilities and was evaluated under both resonant and quasi-static actuation modes. AlN offers a compelling balance of properties, including a high breakdown field, chemical stability, ease of deposition, and compatibility with standard MEMS and IC fabrication processes. These characteristics have encouraged the use of AlN in micromirror designs where structural enhancements, such as leverage-based amplifiers or serpentine beams, are combined with mode-specific actuation strategies.

Although AlN’s high breakdown voltage makes it well suited for quasi-static actuation—allowing stable operation under high driving voltages—many reported designs favor the resonant mode. This preference stems from AlN’s relatively low piezoelectric coefficient (d31), which limits static displacement and makes it challenging to achieve large scan angles through direct actuation alone. By operating near the structure’s mechanical resonance, the resonant mode enables effective displacement amplification while maintaining a low driving voltage. Many AlN-based micromirror designs, therefore, incorporate mechanical resonance and structural leverage mechanisms to enhance optical scan performance. The following section introduces representative AlN-based MEMS micromirrors, classified into 1-DOF and 2-DOF configurations, and compared in terms of scanning mode, optical scan angle, and operating voltage.

1-DOF AlN-based MEMS micromirrors

AlN-based 1-DOF MEMS micromirrors are primarily designed to achieve motion along a single axis, typically for tilting or piston displacement101. Depending on the actuation scheme and mechanical layout, these devices can operate in quasi-static or resonant modes, with motion achieved through various structural strategies, such as folded springs, L-shaped cantilevers, or serpentine beams. For example, in 2018, Shao et al.99 introduced a compact micromirror using two diagonally arranged L-shaped cantilevers (Fig. 5a), which enabled both piston and tilt modes depending on voltage polarity. The device exhibited linear response in both actuation regimes, achieving ±200 nm piston displacement and ±0.15° tilt quasi-statically (±60 VDC and ±30 VDC), and reaching a 4° mirror angle (5 Vpeak, 22.13 kHz) or 1000 nm displacement (5 Vpeak, 63.25 kHz) under resonant actuation.

a Schematic of the AlN-based micromirror design, accompanied by interferometric images showing the mirror surface at rest, during piston motion, and under tilt actuation as captured using a profiler100. b Structural diagram of the proposed AlN micromirror, featuring 250 µm-long L-shaped suspension beams linking the mirror plate to the actuators. Resonant mode shapes were experimentally validated using laser-Doppler vibrometry (LDV)102. c Layout of the AlN-based micromirror structure, where 5 µm-thick L-shaped beams link the actuators to the mirror plate. Each actuator incorporates dual sensor elements positioned at its outer ends. LDV scans illustrate dynamic response under both torsional and piston-mode actuation103. d Schematic of the AlN thin-film-based piezoelectric MEMS micromirror design proposed in the study105. e Actuator-side photograph of the fabricated MEMS micromirror, showing piezoelectric106

Similarly, Meinel et al.102 optimized the mechanical geometry by adjusting spring width and lever arm length through FEM analysis to enhance multi-mode resonant behavior, as illustrated in Fig. 5b. With 3 µm-wide springs, the device achieved a 104.9° scan angle at 20 VAC. However, this performance was accompanied by a lower resonant frequency (1.9 kHz) and a reduced Q-factor compared to designs with wider springs, clearly illustrating the trade-off between large scan angle and dynamic performance. A lower Q-factor increases susceptibility to external disturbances, such as temperature drifts and mechanical vibrations, which can compromise angular stability and precision. To mitigate this issue, Meinel et al.103 from the same research group introduced a follow-up design in 2021, incorporating piezoelectric sensors at the actuator edges, as shown in Fig. 5c. These integrated sensors enabled closed-loop feedback control by providing real-time monitoring of the mirror position, allowing active correction in response to disturbances. As a result, the device achieved a resonant scan angle of 137.9° at 20 VAC and 3385 Hz, while also supporting quasi-static actuation for applications requiring fine control.

In MEMS micromirrors, a large mirror plate area is often essential for applications requiring high optical throughput or wide beam coverage, such as laser scanning and projection systems. However, increasing the mirror size typically lowers the Q-factor due to greater mass and reduced stiffness, which increases energy dissipation and makes the system more vulnerable to mechanical damping99,104. To overcome this trade-off, Lei et al.105 demonstrated a 1-DOF piezoelectric micromirror with a large mirror plate of 6 × 4 mm2 while achieving a high Q-factor of 1851. This was accomplished through the use of serpentine torsion beams and mechanical amplification strategies that reduced effective stiffness and enhanced resonant performance, as shown in Fig. 5d. The device achieved an optical scan angle of 8.2° at 10 Vpeak actuation and 902 Hz resonance.

While most 1-DOF micromirrors are limited to single-axis motion, some designs enable effective 2D coverage through alternative actuation strategies. Pensala et al.106 introduced a 1-DOF micromirror operating in a wobbling mode, using a tripod of three actuators spaced 120° apart, as shown in Fig. 5e. This configuration generated effective 2D angular coverage via in-phase and phase-shifted driving, producing a circular scan pattern. The 4 mm diameter mirror achieved a 30° optical scan at just ≈ 1 Vpeak and 1.6 kHz, with a high Q-factor of ≈4000, offering low-voltage, wide-angle scanning in a resonant operating.

2-DOF AlN-based MEMS micromirrors

2-DOF AlN-based MEMS micromirrors enable bidirectional angular motion critical for applications, such as LiDAR and laser beam steering. These devices are commonly categorized into gimbaled and gimbal-less designs. Gimbaled architectures utilize two rotational frames arranged orthogonally, typically with the outer frame responsible for one axis and the inner mirror responsible for the other. This arrangement allows for decoupled and independently controlled motion, effectively suppressing cross-axis coupling. Gimbal-less configurations, on the other hand, achieve dual-axis actuation within a monolithic structure by using compliant elements, such as serpentine or cross-spring flexures while maintaining mechanical simplicity.

In 2022, Ruotsalainen et al.107 developed a gimbaled 2-DOF AlN-based micromirror with concentric differential actuators aligned along orthogonal axes, as shown in Fig. 6a. Strain-relief serpentine springs were added between the actuator and mirror plate to minimize mechanical stress and cross-axis coupling. Driven at slightly offset resonant frequencies of 915 Hz and 860 Hz under a 3.3 VAC input, the device achieved Lissajous scanning with optical scan angles of 51.2° and 50.8° along the x- and y-axes, respectively, and maintained stable operation with a Q-factor near 18000.

a Schematic showing strain-relief springs with color-coded sensing and actuation components, and simulated displacement profiles of the micromirror under single-axis resonant excitation obtained using COMSOL107. b Layout of the AlN-based micromirror structure, where L-shaped beams link the actuators to the mirror plate. Each actuator incorporates dual sensor elements positioned at its outer ends. LDV scans illustrate dynamic response under both torsional and piston-mode actuation108. c Finite element simulation of a 2-DOF resonantly actuated MEMS micromirror110. d Finite element simulation results illustrating the displacement profiles of the MEMS micromirror under two orthogonal torsional resonance modes109. e Actuator-side photograph of the fabricated MEMS micromirror, showing piezoelectric elements and their electrodes as bright regions on the suspension springs. Simulated tilting modes demonstrate two orthogonal resonant directions, whose superposition enables rotational wobble scanning111

Unlike gimbaled designs with nested frames, gimbal-less 2-DOF MEMS micromirrors achieve bidirectional scanning within a monolithic structure by using compliant flexures, such as serpentine or cross-spring beams. Based on this principle, several representative gimbal-less 2-DOF micromirror designs have been developed108,109,110,111. Among AlN-based gimbal-less micromirrors, the design by Meinel et al.108 stands out for achieving exceptionally large scan angles. As shown in Fig. 6b, their 0.7 mm diameter circular mirror was suspended by orthogonal pairs of torsion beams, enabling wide bidirectional rotation. The best-performing configuration achieved 92.4° at 12.1 kHz (x-axis) and 123.9°at 13.1 kHz (y-axis) under 50 VAC excitation. The high optical scan range came at the cost of mirror plate area, which was kept small to maintain stiffness and resonance. This design also integrated AlN-based angle sensors that provided real-time feedback.

In contrast, Senger et al. conducted two studies targeting applications that require large mirror plate areas, such as smart headlights109 and laser material processing110. Among these, their 2021 work specifically focused on upscaling the mirror plate area while retaining resonant operation110. As illustrated in Fig. 6c, they developed a series of micromirrors for laser material processing with mirror diameters of 7 and 10 mm. Despite the increased mass, the devices successfully preserved orthogonal torsional modes and achieved optical scan angles of 5° at 1288 Hz and 3° at 564 Hz, respectively, under ±40 VAC actuation.

Senger et al.109 also demonstrated a gimbal-less design for smart headlight systems. Their device integrated a 5.5 mm circular mirror actuated by concentric AlN thin-film actuator rings, as shown in Fig. 6d. The outer and inner rings independently controlled x- and y-axis motion through differential driving. Resonant operation at 2.26 and 2.30 kHz yielded optical scan angles of 55° and 30°, respectively, under ±40 VAC. Another notable contribution by Ruotsalainen et al.111 introduced a rotationally symmetric micromirror design with discrete AlN layers for actuation and sensing, illustrated in Fig. 6e. Operated under vacuum, the device exhibited resonant frequencies of 1332 and 1297 Hz for the x- and y-axes, respectively. Under 5 VAC single-axis driving, it achieved 21.2° scan angle, and in dual-axis mode, reached 42.4° and 32.4°.

AlScN-based MEMS micromirrors

The first AlScN-based MEMS micromirror was presented by Gu-Stoppel et al.112 at a conference in 2019, and was later detailed in a journal publication in 202060. Since then, AlScN has emerged as a promising alternative to AlN for enhancing micromirror actuation performance, offering a significantly higher piezoelectric coefficient that enables larger tilt angles at lower actuation voltages. Even with these enhancements, the fabrication process of AlScN thin films remains largely compatible with established AlN processes, requiring only modifications in sputtering targets and etch rate management113. Based on these advantages, AlScN-based MEMS micromirrors have evolved into two primary structural configurations: three-level and single-layer constructions. Each configuration offers different advantages depending on the target application.

Figure 7 compares representative MEMS mirror structures based on three-level and single-layer constructions, illustrating their overall layouts and key functional components. As shown in Fig. 7a, the three-level construction incorporates a separately fabricated mirror plate, actuator, and supporting pillar60,112,114,115,116,117,118,119,120. This stacked structure provides enhanced mechanical leverage, allowing for larger mirror size, larger tilt angles, and improved multi-axis movement. Additionally, by minimizing non-reflective regions, this design maximizes the fill factor, improving optical efficiency for applications, such as LiDAR and advanced projection systems. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 7b, the single-layer construction integrates both the mirror plate and the actuator onto the same wafer113,121,122. This approach simplifies fabrication and enhances mechanical robustness. Its compact design supports high-speed operation and facilitates monolithic integration with existing MEMS platforms, making it suitable for applications requiring fast response times and minimal assembly complexity. Both configurations have been actively investigated, with their selection typically depending on specific application requirements, such as scan angle, resonant frequency, or fill factor. The following sections review key developments in each design, highlighting their performance achievements and potential for MEMS mirror applications.

Three-level constructed MEMS micromirrors

A representative class of AlScN-based MEMS mirrors is the three-level constructed architecture, which enables integration of large-aperture mirrors with concealed actuators in compact form factors. In 2020, Gu-Stoppel et al.60 introduced a 3 × 3 quasi-static mirror array based on Al0.76Sc0.24N thin films, where a four-hidden-actuator configuration enabled precise 2D beam steering with high linearity and long-term mechanical stability. The system achieved a mechanical tilt of ±14° at 150 VDC, confirming the potential of AlScN for large-angle quasi-static applications, as shown in Fig. 8a.

a Adoption of a three-level mirror matrix architecture featuring hidden actuators and through-silicon vias for vertical interconnection, enabling high-linearity 2D scanning60. b Development of a scalable design and manufacturing platform based on glass frit wafer bonding and 3D integration, supporting multiple aperture sizes and structural robustness analysis via FEM simulation114. c Demonstration of multifunctional scanning capabilities—including quasi-static and resonant modes—with full 3D fabrication and ultra-low-voltage operation, enabling diverse scan trajectories115. d Systematic exploration of design parameter trade-offs (mirror size, spring stiffness, piezoelectric material), highlighting the performance advantages of AlScN over AlN in actuation efficiency and device scalability116

Building on this, Gu-Stoppel et al.114 in 2021 proposed a unified fabrication platform utilizing glass frit bonding for wafer-level 3D assembly, which supported mirrors with up to 10 mm aperture without requiring vacuum sealing (Fig. 8b). Finite element simulations performed in this study provided key insight into the mechanical constraints of scaling: mirrors with larger mass and area, while desirable for optical throughput, were more susceptible to shock due to lower resonant frequencies. The simulated mechanical tilt of 5.2° at 150 VDC for the 10 mm AlScN mirror highlights its viability for robust quasi-static operation at scale.

Further advancing this architecture, Hwang et al.115 in 2023 demonstrated a fully 3D-integrated AlScN MEMS mirror supporting both quasi-static and resonant actuation, as shown in Fig. 8c. The device experimentally achieved multiple scanning modes—including raster, spiral, and Lissajous patterns—at remarkably low driving voltages. Specifically, it exhibited a TOSA of 10.4° at ±20 VDC in quasi-static mode and 16° at 0.25 Vpeak in resonant scanning, underscoring the electromechanical efficiency and versatility of AlScN-based actuation for multifunctional beam steering.

Recognizing the trade-offs inherent in structural design, Hwang et al.116 subsequently investigated how parameters, such as mirror diameter, polysilicon thickness, and spring stiffness influence performance across both actuation regimes (Fig. 8d). Their comparative study revealed that resonant frequency is primarily governed by mirror mass and structural stiffness, favoring smaller mirrors with thicker support layers, whereas quasi-static deflection benefits from compliant suspensions and thinner layers. Critically, AlScN showed clear advantages over AlN in actuation efficiency, achieving a 20° TOSA at ±70 VDC, while comparable AlN-based designs required substantially higher voltages. These findings emphasize the importance of material selection not only in enhancing performance but also in reducing power budgets for large-angle MEMS mirrors. A detailed comparison between AlN and AlScN is provided in Section 4.3, Comparative Analysis and Discussion on AlN- and AlScN-based MEMS Micromirrors.

In 2024, Yang et al.117 developed a two-axis AlScN-based MEMS micromirror optimized for water-immersible operation, as shown in Fig. 9a. Fabricated using an 8 inch standard MEMS process, the device features a 10 mm circular mirror plate suspended by four piezoelectric actuators via flexible cantilever springs. The mirror demonstrated bidirectional quasi-static tilt with excellent linearity (99.3%) and achieved resonant scan angles of ±5° in air and ±2° in water at 90 VAC. This study demonstrates how AlScN’s high dielectric strength and mechanical robustness enable stable operation in fluidic environments. Furthermore, its compatibility with large-diameter substrates and batch MEMS processes facilitates scalable integration, offering a pathway to overcome fabrication and packaging challenges commonly encountered in immersion-capable MEMS mirrors.

a A water-immersible two-axis MEMS mirror designed for photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging, integrating a honeycomb-reinforced mirror to suppress cavitation and enhance structural stability during immersion117. b A multi-degree-of-freedom MEMS mirror featuring a vertically assembled 5 mm square mirror and concealed S-shaped actuators, enabling independent tip, tilt, and piston control with high fill factor and optical efficiency118. c A fast steering mirror optimized for free-space optical communication, employing rib-reinforced AlScN-actuated beams to enhance resonant stiffness and achieve sub-millisecond response through double-step driving119. d A compact FSM designed for laser inter-satellite links, integrating a stress-enhanced piezoresistive sensor for in-situ angular feedback, supporting precise beam control with sub-microradian resolution and low surface deformation120

In the same year, Zhang et al.118 reported an Al0.904Sc0.096N-based quasi-static MEMS micromirror supporting multi-DOF actuation, as shown in Fig. 9b. The actuator employed a three-stage cantilever array with an S-shaped layout fully concealed beneath a 5 × 5 mm2 mirror plate, resulting in a near-100% fill factor and high optical throughput. The device delivered a tilt range of ±2.2° and a piston displacement of ±54.9 μm under ±50 VDC, while maintaining excellent linearity and bidirectional symmetry. This design highlights the ability of AlScN actuators to support compact and multi-axis configurations.

These developments further underscore the structural versatility of AlScN, enabling both large quasi-static deflections and efficient low-voltage resonant operation within compact beam steering platforms. Such design flexibility supports a range of applications requiring trade-offs among performance, stability, and integration.

In 2024, Yang et al.119 developed a high-speed MEMS fast steering mirror (FSM) on an 8-inch AlScN platform for free-space optical communication, as shown in Fig. 9c. The device features a 10 mm high-reflectivity mirror plate supported by four AlScN-actuated cantilever beams and was packaged using wafer-level eutectic bonding. To enhance dynamic performance, a double-step drive method was applied, reducing the step response time from 400 ms (open-loop) to 0.5 ms (closed-loop). The mirror achieved a tilt angle of 1.38 mrad at 68 VDC, illustrating the potential of AlScN for compact and responsive beam steering applications.

In 2025, Xue et al.120 reported a compact AlScN-based MEMS FSM tailored for laser inter-satellite link systems, as shown in Fig. 9d. The device incorporated a 10 mm optical mirror and was housed in a 26 × 22 × 3 mm3 package. It achieved resonant frequencies above 1 kHz and a minimum angular resolution of 0.3 μrad. A TOSA of 8.4 mrad was obtained under ±110 VDC. Despite its compact footprint, the device maintained low surface deformation (<2 nm) and a fast step response (0.41 ms), making it suitable for spaceborne optical communication platforms requiring precise and stable operation.

Together, these FSM-oriented studies demonstrate that AlScN-based actuators fulfill key requirements, such as kilohertz-range resonance, sub-milliradian angular precision, and minimal surface deformation. Unlike large-angle scanning MEMS mirrors, FSMs prioritize fine angular control, rapid response, and tight integration. The adoption of AlScN in these systems has enabled high-speed and compact optical modules, expanding its role beyond quasi-static applications to dynamic beam steering in highly constrained environments.

Single-layer constructed MEMS micromirrors

In 2022, Stoeckel et al.113 investigated the static high-voltage actuation of piezoelectric MEMS scanning mirrors using AlN and AlScN thin films. As shown in Fig. 10a, two mirror designs (2 × 3 mm² and 4 × 6 mm²) were fabricated, incorporating 600 nm AlN and 2000 nm Al0.68Sc0.32N as the piezoelectric transducer materials. The study directly compared the mirror performance under identical structural designs but with different piezoelectric materials. The quantitative analysis is provided in Section 4.3, Comparative Analysis and Discussion on AlN- and AlScN-based MEMS Micromirrors. The AlScN-based mirror demonstrated a significantly enhanced static scan angle, reaching 55.6° at 220 VDC, in contrast to the lower angular deflection observed in the AlN-based counterpart.

a Schematic and motion scan images of the proposed micromirror design113. Schematic, photograph, and SEM images of MEMS mirrors: b with a gimbal-less structure and c with a gimbaled structure122. d Photographs of fabricated micromirrors, large-angle scanning operation, simulation results of operation modes, and Lissajous figure generated by the biaxial micromirror121

In 2022, Liu et al.122 explored AlScN-based MEMS mirrors with large field-of-view scanning capabilities for LiDAR systems. Two designs were evaluated: a gimbal-less mirror (D = 5 mm) and gimbaled mirrors (D = 1.5 mm and 3 mm). Figure 10b, c present the MEMS mirrors with gimbal-less and gimbaled structures, respectively. Gimbal-less mirrors offer a high fill factor but often experience mechanical coupling between fast and slow axes. In contrast, gimbaled mirrors use a dedicated frame to physically decouple the two axes, allowing independent control but reducing the fill factor due to added structural layers. Experimentally, the 5.0 mm gimbal-less mirror (fill factor: 19.6%) achieved optical tilt angles of 11.4° (x-axis) and 8.6° (y-axis) at 30 VAC, with resonant frequencies of 1272 and 1325 Hz. The 1.5 mm gimbaled mirror (fill factor: 7.6%) achieved 22.6° (x-axis) and 4.1° (y-axis) at the same voltage, with resonant frequencies of 3187 and 8187 Hz.

In 2024, Huang et al.121 developed a biaxial Lissajous scanning piezoelectric MEMS micromirror with a 5 mm diameter mirror plate for LiDAR applications, as shown in Fig. 10d. To support large-angle scanning, the design incorporated a stress-dispersion structure to prevent silicon fracture, vacuum packaging to reduce air damping, and a frequency-sweep driving method for accurate identification of nonlinear resonances. With a 45 Vpeak input in air, the device achieved TOSAs of 21.0° (x-axis, 816 Hz) and 24.4° (y-axis, 928 Hz). In vacuum, these values increased dramatically to 102.8° and 104.8° at slightly lower frequencies (810 and 891 Hz), underscoring the significant impact of air damping control.

Comparative analysis and discussion on AlN- and AlScN-based MEMS micromirrors

To highlight the practical advantages of AlScN over AlN, this section summarizes key experimental and simulation studies that have quantitatively compared their performance in MEMS micromirror applications. The analysis focuses on normalized metrics, such as tilt angle per electric field and scan range under identical structural conditions.

Gu-Stoppel et al.60 performed FEM simulations using AlN material parameters from the simulation software’s material library. To approximate the behavior of AlScN, the piezoelectric coefficients were adapted by applying an amplification factors of 1.5 and 2.5, based on experimentally measured differences between AlN and AlScN. The simulation results showed that, for the same device design, the mechanical tilting angle increased from 7° to 11° when the higher piezoelectric response was applied. Subsequently, Gu-Stoppel et al.114 reported that, based on FEM simulations calibrated with piezoelectric coefficients, the achievable tilt angle of AlN-based MEMS mirrors was estimated to be approximately 50% of that of their AlScN-based counterparts.

Stoeckel et al.113 reached a similar conclusion: substituting AlN with Al0.68Sc0.32N increased the static deflection per unit electric field by a factor of 3.5. To ensure a fair comparison, their analysis was normalized by electric field rather than drive voltage, as both devices shared the same geometry but differed in piezoelectric film thickness (600 nm for AlN and 2 µm for Al0.68Sc0.32), as illustrated in Fig. 11a. For instance, at an electric field of 100 MV/m, the tilt angles were 1.2° for AlN and 4.3° for AlScN (Fig. 11b). Resonant behavior further reinforces this advantage: despite a reduced resonance frequency due to lower structural stiffness (3.44 kHz for AlN and 1.82 kHz for Al0.68Sc0.32), the AlScN mirror achieved a resonant tilt angle of 11.9° at 1 MV/m, compared to only 2.8° for AlN (Fig. 11c), representing a four-fold improvement that underscores the superior actuation efficiency of AlScN.

a Single-layer MEMS mirror design113, b mechanical tilt angle versus electric field, and c frequency response. d Three-level MEMS mirror design116, e total optical scan angle versus applied voltage, and f laser spot images on a polar target, showing ±10° deflection at 140 Vpp (AlScN) and 240 Vpp (AlN), respectively

Hwang et al.116 reported a comparison of the quasi-static performance of AlN-based and AlScN-based mirrors fabricated using the same spring structure design, as shown in Fig. 11d. Figure 11e shows that achieving the same TOSA of 20° required a significantly higher drive voltage for the AlN-based device (240 Vpp) than for the AlScN-based counterpart (140 Vpp). Figure 11f presents direct laser-spot images on a polar target, confirming a TOSA of 20°: the top row (P1, red frame) shows the AlScN mirror reaching ±10° at 140 Vpp, whereas the bottom row (P2) shows the AlN mirror achieving the same ±10° deflection only at 240 Vpp.

Zhang et al.118 further demonstrated that, under identical device structures, replacing AlN with AlScN improved both tilt and piston-mode actuation performance. Specifically, tilt sensitivities reached up to 0.0436°/V, and piston displacement increased to 54.9 µm at 50 V, reflecting a 16.6% enhancement compared to the AlN-based design. Collectively, these experimental and simulation results underscore the significant advantages of AlScN-based transducer materials in enhancing the performance of piezoelectric MEMS mirrors.

Reported MEMS micromirrors utilizing piezoelectric AlN and AlScN are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4, respectively. The comparison includes piezoelectric material, mirror area, chip size, DOF, scanning mode, resonant frequency, figure of merit (FoM), drive voltage, and optical scan angle, providing a comprehensive assessment of their characteristics and performance. To provide a fair and mode-specific performance indicator, FoM is defined differently depending on the scanning mode. For resonant-mode devices, FoM = mirror area (mm2) × optical scan angle (°) × resonant frequency (kHz), capturing the benefit of dynamic amplification. For quasi-static devices, FoM = mirror area (mm2) × optical scan angle (°), which reflects performance under static or low-frequency operation. This separation enables objective cross-comparison while accounting for fundamental differences in actuation behavior. In Table 3, the devices are grouped by DOF (1-DOF and 2-DOF), which reflects the mirror’s scanning capability, and listed in chronological order within each category to aid comparative analysis. In Table 4, AlScN-based micromirrors are further classified into three-level and single-layer constructions, as these structural distinctions influence fill factor, fabrication complexity, and mechanical behavior. This classification scheme ensures consistency and highlights the evolution of MEMS mirror architectures over time.

Figure 12 compares the performance distribution of MEMS micromirrors based on piezoelectric AlN and AlScN in terms of mirror area, optical scan angle, and resonant frequency. In the resonant scanning mode (Fig. 12a), most AlN-based devices exhibit relatively high FoM values. This is primarily due to their higher resonant frequencies, despite having smaller scan angles and moderate mirror areas. Meinel et al.102,103,108 reported optical scan angles exceeding 100° using AlN-based actuators with relatively small mirror plates. Building on their AlN-based design, they proposed that adopting AlScN could further enhance actuation capability by leveraging its higher piezoelectric response. In the quasi-static mode (Fig. 12b), a clear trend is observed in which recent studies employing AlScN materials have achieved significantly larger optical scan angles across a wide range of mirror sizes. This reflects AlScN’s advantage in enabling both large-aperture actuation and wide-angle scanning, supported by its enhanced piezoelectric properties. Among the quasi-static AlScN-based micromirrors, those with mirror diameters greater than 10 mm have been implemented using three-level constructions114,117,119,120, in which large-aperture mirror plates fabricated on separate wafers are bonded to actuator structures via vertical pillars. In particular, Yang et al.117 demonstrated quasi-static and resonant actuation within a single mirror device. Finally, it is important to note that FoM values can be significantly affected by the operating environment. Devices tested in vacuum exhibit higher FoM than those tested in air, due to reduced viscous damping and the ability to reach larger deflections at resonance109,121.

Piezoelectric MEMS mirror applications

AlScN-based piezoelectric MEMS mirrors are emerging as technically viable alternatives to conventional AlN and PZT-based devices in beam steering applications. Although their commercial implementation remains limited, recent progress in thin-film deposition, mechanical design, and integration technologies has significantly advanced their development toward practical use. Device-level studies have demonstrated that AlScN MEMS mirrors can achieve high resonant frequencies and large optical scan angles, highlighting their potential for demanding applications, such as LiDAR. Although full system-level validation remains limited, these results establish the feasibility of AlScN-based designs and motivate further comparative benchmarking against existing PZT and AlN devices.

Specifically, the material’s high stiffness and breakdown strength make it ideal for high-frequency resonant scanning, while its linear piezoelectric response and low dielectric loss enable stable quasi-static actuation over large angular ranges. As shown in Fig. 13, this section reviews five representative application domains in which AlScN-based MEMS mirrors have demonstrated either validated performance or strong design potential: laser projection systems, laser material processing, quantum optics, LiDAR, and high-speed laser tracking. In each case, we highlight how the intrinsic properties of AlScN enable performance improvements or design options not readily achievable with conventional piezoelectric materials.

a Dual-axis laser projection for automotive smart headlights109. b Compact image projection in augmented reality smart glasses124. c High-power laser material processing with circular scanning110. d Cold-atom control in quantum optics using quasi-static beam steering125. e Wide-angle LiDAR beam steering for 3D sensing126. f High-speed and stable laser tracking in dynamic environments127

High-frequency laser projection systems: smart headlights & AR glasses

Laser beam scanning (LBS) projection systems, commonly implemented in automotive smart headlights and near-eye AR displays, require MEMS mirrors capable of high-frequency resonant operation and wide optical scan angles. These systems typically rely on resonant-mode operation to achieve the high-speed beam traversal needed for real-time image rendering. Additionally, dual-axis actuation is essential for achieving a high spatial fill factor—defined here as the degree of image area coverage—in raster or Lissajous scanning patterns. PZT-based MEMS mirrors have been used due to their strong actuation force, but their mechanical reliability and long-term stability can be limiting123.

More recently, AlN-based devices have been adopted in vacuum-packaged, dual-axis resonant configurations to realize large scan angles with high Q-factors. As shown in Fig. 13a, AlN MEMS mirrors have demonstrated Lissajous scanning in smart headlight applications109. In AR smartglasses124, similar resonant dual-axis mirrors project images directly onto the retina via diffractive waveguides, eliminating the need for bulky beam expansion optics (Fig. 13b). The combination of compact form factor, low power consumption, and wide field-of-view makes these systems well-suited for wearable displays. Given its enhanced piezoelectric response and ability to sustain high Q-factor operation, AlScN is well positioned to surpass both PZT and AlN in resonant-mode LBS modules for automotive and wearable applications requiring wide-angle and high-frequency scanning.

Laser material processing with high-power resonant scanning

Laser-based micromachining and precision material processing require MEMS mirrors capable of delivering high-speed, repeatable scan patterns with large optical apertures and minimal thermal drift. Resonant-mode operation is particularly advantageous in this context due to its energy efficiency and trajectory stability. As shown in Fig. 13c, recent implementations have demonstrated large-aperture (D = 7–10 mm) AlN-based MEMS mirrors optimized for circular scanning of high-power lasers at 515 and 1050 nm110. These devices employ vacuum-packaged gimbal-less architectures to achieve high-amplitude torsional motion, while integrated piezoelectric sensors enable closed-loop control for precise beam positioning. Building on this design approach, AlScN’s enhanced piezoelectric response and electromechanical coupling make it well suited for high-frequency operation.

Cold-atom control and quantum optics with MEMS scanning mirrors

AlN MEMS mirrors have recently been adopted in quantum optics and cold-atom systems, where laser beams must be precisely directed to control the behavior of trapped atoms cooled to near absolute zero. These systems use laser steering to locally excite or probe atomic clouds, enabling applications, such as region-selective measurement, optical trapping, or shaping of quantum potentials. As shown in Fig. 13d, dual-axis MEMS mirrors have been used to scan resonant beams through ultracold atom ensembles to create programmable illumination patterns125. Such applications require stable angular displacement and low power consumption. These cold-atom experiments typically employ quasi-static scanning modes to achieve stable and precise beam placement, rather than resonant driving, which could introduce undesirable vibrations. Like AlN, AlScN supports monolithic integration and low dielectric loss. Additionally, its enhanced piezoelectric response offers potential advantages for precise, energy-efficient beam steering in cold-atom experiments.

Wide-angle MEMS beam steering for LiDAR systems

Beam-steering LiDAR systems demand MEMS mirrors with large optical scan angles, high resonant frequencies, and strong mechanical resilience, especially for applications in autonomous vehicles, drones, and mobile robotics. According to typical design baselines11, LiDAR mirrors must achieve field-of-view angles over 25°, diameters of at least 2 mm, and resonance frequencies above 0.8 kHz to ensure reliable 3D sensing and vibration immunity. As shown in Fig. 13e, a coaxial LiDAR architecture requires the mirror to dynamically steer both the emitted and received beams to enable 3D scene reconstruction via time-of-flight measurements126.

Recent AlScN-based MEMS mirrors have demonstrated performance metrics that align well with these requirements. For instance, gimbal-less resonant designs with 5 mm apertures achieved dual-axis optical scan angles exceeding 100° by incorporating vacuum packaging and mechanical stress-dispersion structures121. Separately, gimbaled AlScN mirrors with 1.5 mm and 3 mm apertures showed more than a tenfold increase in the optical field of view under 4 Pa vacuum conditions122. In addition to wide-angle operation, these mirrors exhibit excellent mechanical durability. The AlScN MEMS mirror successfully withstood 900 g shock and 20 g vibration tests, verifying its robustness for automotive-grade LiDAR modules121. These results highlight the suitability of AlScN-based MEMS mirrors for next-generation LiDAR systems, where high-speed, large-angle, and vibration-resilient performance is essential.

High-speed laser tracking with MEMS mirrors

Laser tracking systems require rapid angular actuation, real-time feedback, and compact integration to support applications, such as optical communication, UAV guidance, and autonomous object tracking. Traditional mechanical systems often fall short due to slow response, susceptibility to ambient light interference, and large form factors. In contrast, AlScN MEMS mirrors offer fast response, robustness under varying illumination, and miniaturized designs. As shown in Fig. 13f, recent implementations have achieved tracking speeds up to 3.77 m/s at a 5 m distance and demonstrated stable operation over 110 m, even under dynamic conditions, such as UAV motion127. These results were enabled through co-optimization of MEMS mirror design, control algorithms, and optical filtering.

Notably, the working principle of laser tracking systems often requires quasi-static actuation rather than resonant operation. Operating in resonance may lead to uncontrollable vibrations and degraded tracking stability. AlScN-based MEMS mirrors are particularly advantageous in this context due to their ability to maintain stable quasi-static actuation over wide angular ranges, supported by their strong piezoelectric response and high breakdown field. These features make AlScN MEMS mirrors promising candidates for advanced laser tracking systems that require both precise angular control and stable performance across varying tracking scenarios.

Conclusion

AlN has been widely adopted in MEMS micromirrors due to its stable mechanical properties, environmental robustness, and compatibility with standard CMOS processes. However, its intrinsically low piezoelectric response limits the achievable optical scan angles, which can constrain design flexibility in applications requiring wide angular motion. To overcome this limitation, AlScN has emerged as a promising alternative. By incorporating scandium into the AlN lattice—typically at concentrations between 20 and 43%—the piezoelectric response is significantly enhanced. This enhancement enables AlScN-based micromirrors to achieve larger mechanical tilt angles and, consequently, wider optical scan angles than their AlN counterparts. Rather than entirely replacing AlN, AlScN serves as a functional enhancement, offering higher piezoelectric coefficients in applications that demand larger actuation amplitudes or lower operating voltages.

However, increasing the Sc content introduces several design trade-offs. Higher concentrations of Sc reduce the Young’s modulus and hardness of the material, potentially compromising the mechanical stability of micromirror structures, particularly in designs involving large mirrors or long torsional beams. Furthermore, excessive Sc doping beyond ~50% can trigger a phase transition from the piezoelectric wurtzite phase to a non-piezoelectric rock-salt structure, severely degrading functional performance. In summary, AlScN significantly broadens the design space for MEMS micromirrors by enabling improved actuation efficiency and larger scan angles. Nevertheless, to fully exploit these advantages, careful optimization of Sc concentration and structural geometry is essential to ensure long-term reliability and performance stability.

While this review has primarily focused on micromirror designs, the broader potential of Sc-doped AlN extends across a wide spectrum of MEMS applications. Its enhanced piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties have facilitated significant advances in RF filters for 5 G/6 G systems128, MEMS speakers129,130, energy harvesters131, high-temperature non-volatile memory132, Lamb wave resonators133, surface acoustic wave resonators134, and integrated sensors designed for harsh environments135. Moderate Sc concentrations (x ≈ 0.27–0.30) are increasingly favored in industrial settings, offering a practical trade-off between performance enhancement and structural stability41. These developments position AlScN not only as an upgrade to AlN in select applications, but also as a versatile platform for multifunctional and highly integrated MEMS technologies.

At the same time, AlN continues to offer unique advantages in specific application domains. Its excellent chemical stability, high thermal conductivity, and compatibility with back-end CMOS processes make it particularly well suited for sensors, energy harvesters, and high-frequency acoustic devices where environmental resilience and long-term reliability are critical29. Consequently, material selection between AlN and AlScN should be guided by the specific performance requirements of the target application, carefully balancing piezoelectric response, mechanical integrity, and process integration. Rather than offering a one-size-fits-all solution, AlN and AlScN each fulfill distinct roles and should be strategically selected based on specific actuation needs, reliability constraints, and integration requirements in MEMS device development.

References

Wang, X., Xie, Y., Liang, H. & Zhong, N. Analysis of distortion based on 2D MEMS micromirror scanning projection system. Micromachines 12, 818 (2021).

Xu, B., Xu, C., Ji, Y., Zhang, B. & Li, J. Lissajous MEMS laser beam scanner with uniform and high fill-factor projection for augmented reality display. Opt. Express 31, 35164–35177 (2023).

Pollock, C., Pardo, F., Imboden, M. & Bishop, D. Open loop control theory algorithms for high-speed 3D MEMS optical switches. Opt. Express 28, 2010–2019 (2020).

An, Y. et al. A 1× 20 MEMS mirror array with large scan angle and low driving voltage for optical wavelength-selective switches. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 324, 112689 (2021).

Sun, J. et al. 3D in vivo optical coherence tomography based on a low-voltage, large-scan-range 2D MEMS mirror. Opt. Express 18, 12065–12075 (2010).

Gorecki, C. & Bargiel, S. MEMS scanning mirrors for optical coherence tomography. Photonics 8, 6 (2020).