Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder characterized by recurrent upper airway obstructions, leading to substantial health burdens and socioeconomic costs. This study aimed to identify Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Differentially Expressed Genes (HMRDEGs) and evaluate their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets for OSA. Transcriptomic data from GSE135917 and GSE38792 in the GEO database were analyzed using the limma package to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs), which were subsequently intersected with hypoxia- and mitophagy-related gene sets(HMRGs) curated from GeneCards and PubMed. A total of 24 HMRDEGs were identified, and four hub genes—NLRP3, MAPK9, RBBP4, and CLINT1—were used to construct a diagnostic model that demonstrated excellent discrimination (AUC = 0.982 in the training set and 0.812 in the validation set). Gene Ontology and KEGG analyses linked these genes to protein catabolism and autophagy pathways, while immune-cell infiltration profiling associated them with specific leukocyte subsets. Collectively, our findings underscore hypoxia–mitophagy crosstalk as a central mechanism in OSA and present a robust biomarker panel with therapeutic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent sleep disorder marked by recurrent upper-airway collapse during sleep, which causes intermittent hypoxia and a range of adverse sequelae1. Beyond diminishing quality of life, OSA is strongly associated with cardiovascular disease, metabolic dysregulation, and cognitive impairment2. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the first-line treatment, but its real-world effectiveness is limited by poor adherence and discomfort. Consequently, there is an urgent need for more effective and patient-friendly management strategies3.

Large-scale omics studies published in 2025 have refined the molecular landscape of OSA. Dasgupta et al. applied cross-disease network analysis and found four genes—C1GALT1, TMEM106B, ZNF117, and ZNF486—concurrently up-regulated in both OSA and lung cancer, implicating hypoxia-driven pathways that transcend single-disease boundaries4.Complementing this work, Zhou et al. combined transcriptomic and immunoinformatics data, validated four immune-related genes (IL33, EIF2AK2, IL10RB and ANGPTL1) as diagnostic biomarkers, and recorded pronounced immune-cell dysregulation in visceral adipose tissue of OSA patients5.Together, these studies highlight hypoxia-induced metabolic stress and immune perturbation as central mechanisms in OSA, supporting our focus on hypoxia- and mitophagy-related differentially expressed genes (HMRDEGs).

This study systematically examines the contribution of hypoxia- and mitophagy-related differentially expressed genes (HMRDEGs) to OSA. We propose that dysregulation of these genes not only drives OSA pathogenesis but also offers biomarker and therapeutic potential. Leveraging an integrated bioinformatics workflow, we identified and validated HMRDEGs, explored their mechanistic relevance, and assessed their diagnostic utility. A four-gene logistic model incorporating NLRP3, MAPK9, RBBP4, and CLINT1 achieved excellent discrimination, with an AUC of 0.982 in the training set and 0.812 in an independent validation set. These findings highlight the clinical promise of the HMRDEG signature for early diagnosis and targeted intervention in OSA.

Materials and methods

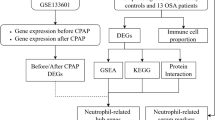

Data download

We used the R package GEOquery6(Version 2.70.0) download obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) datasets GSE1359177 and GSE387928 from GEO9 database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). The samples of GSE135917 and GSE38792 were all from Homo sapiens. The Tissue source of GSE135917 was Subcutaneous Fat Tissue. In dataset GSE38792, the tissue source was Visceral adipose tissue. The chip platform utilized for the datasets GSE135917 and GSE38792 was GPL6244, with detailed information presented in Table 1. Specifically, dataset GSE135917 comprised 34 samples from individuals with OSA and 8 control samples. In contrast, dataset GSE38792 included 10 OSA samples alongside 8 controls. The present research included all specimens from the aforementioned datasets.

GeneCards database10 (https://www.genecards.org/) offers extensive details regarding human genes.Initially, we employed ‘Hypoxia’ as our primary search term and focused exclusively on ‘Protein Coding’ genes that exhibited a Relevance Score exceeding > 1 in order to pinpoint hypoxia-related genes (HRGs). Subsequently, we conducted a search for ‘Hypoxia’ within the PubMed database (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to gather hypoxia-associated gene sets documented in previously published studies11,12,13. Following the processes of integration and eliminating redundancies, we successfully identified a total of 2461 unique HRGs. Similarly, utilizing “Mitophagy” as the search term, we filtered the results to include solely those mitochondrial autophagy-related genes (MRGs) that are classified as “Protein Coding” and possess a “Relevance Score > 1”. Subsequently, we used “Mitophagy” as the keyword on the PubMed website (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to obtain the mitochondrial autophagy-related gene sets from published literature14,15,16,17. Following the integration of data and the elimination of duplicate entries, a cumulative total of 1710 MRGs was identified. Ultimately, an intersection of the hypoxia and mitophagy-related genes yielded a total of 561 HMRGs, with detailed information provided in Table S1.

Finally, the R package limma18 (Version 3.58.1) was used to annotate and normalize the OSA datasets GSE135917 and GSE38792, respectively. A boxplot was employed to evaluate and contrast the expression levels of the datasets before and after normalization.

Differentially expressed genes related to obstructive sleep apnea-associated hypoxia and mitophagy

In accordance with the sample classification outlined in GSE135917, the samples were divided into two distinct cohorts: the OSA group and the Control group. The R package limma18(Version 3.58.1) was employed to assess the differences between the OSA group and the Control group. A criterion of |logFC| > 0.5 and an adjusted p-value (adj.p) < 0.05 were defined to pinpoint Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs). Specifically, genes that demonstrated logFC > 0.5 in conjunction with adj.p < 0.05 were identified as Up-regulated DEGs, while genes with logFC < -0.5 and adj.p < 0.05 were categorized as Down-regulated DEGs. The Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) approach was applied for p-value correction. The findings from the differential analysis were visually depicted using the R package ggplot2 (Version 3.4.4), facilitating the generation of a volcano plot.

To determine the hypoxia and mitophagy-related differentially expressed genes (HMRDEGs) associated with OSA, DEGs were selected from the GSE135917 dataset based on the criteria of |logFC| > 0.5 and an adjusted p-value of less than 0.05. These DEGs were then compared with known hypoxia and mitochondrial autophagy-related genes (HMRGs). A Venn diagram was subsequently created to illustrate the genes that overlapped between the two sets. Additionally, a heatmap was utilized to present the top 20 HMRDEGs.The R package14 pheatmap (Version 1.0.12) was utilized to generate a heatmap illustrating the TOP20 HMRDEGs.

Differential expression verification and ROC curve analysis

To investigate the variations in the expression levels of HMRDEGs between the OSA group and the Control group within the GSE135917 dataset, a comparative analysis was conducted.This analysis yielded a visual representation of the group comparison focused on the HMRDEGs.Finally, the R package pROC19 (Version 1.18.5) was used to plot the ROC Curve of HMRDEGs and calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) value. To assess the diagnostic capability of HMRDEGs in relation to the onset of OSA, the AUC of the ROC curve is utilized. Typically, AUC values range from 0.5 to 1, with values nearing 1 suggesting an excellent diagnostic performance. In detail, an AUC falling between 0.5 and 0.7 indicates low diagnostic accuracy, while an AUC ranging from 0.7 to 0.9 demonstrates moderate accuracy. Conversely, an AUC exceeding 0.9 is indicative of a high degree of accuracy in diagnosis.

Gene ontology (GO) and pathway (KEGG) enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) analysis20serves as a widely utilized approach for conducting extensive functional enrichment investigations, encompassing three primary categories: Biological Process (BP), Cell Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)21,22,23database is extensively utilized for the storage of data pertaining to genomes, biological pathways, diseases, and pharmacological agents.We conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses on the HMRDEGs utilizing the R package clusterProfiler24 (Version 4.10.0). The criteria for entry screening were set at adj.p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25. The adj.p was conducted using the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method.

Establishment of diagnostic model for obstructive sleep apnea

To develop a diagnostic model for OSA using the GSE135917 dataset, a logistic regression analysis was conducted on the HMRDEGs. The primary objective of this analysis was to investigate the relationship between independent variables and dependent variables, particularly emphasizing binary outcomes, which include OSA and control samples.HMRDEGs were determined based on a significance threshold of p < 0.05, which subsequently facilitated the development of a logistic regression model. Following this, the collective expression of the identified HMRDEGs within the logistic regression framework was visually represented through a forest plot.

Subsequently, utilizing the HMRDEGs incorporated within the Logistic regression model, the SVM (Support Vector Machine)25 algorithm was used to develop an SVM model based on the number of genes with the highest accuracy and the lowest error rate. The HMRDEGs were screened.

Finally, LASSO was performed using the R package glmnet26 (Version 4.1-8) with set.seed (500) and family= “binomial” as parameters based on the HMRDEGs included in the SVM model. The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression analysis is fundamentally grounded in linear regression techniques. This methodology introduces a penalty term, denoted as lambda times the absolute value of the slope, which serves to reduce the likelihood of overfitting while simultaneously improving the model’s ability to generalize. The results obtained from the LASSO regression analysis were represented via a diagnostic model diagram and a variable trajectory diagram. Consequently, this analysis facilitated the development of a diagnostic model for OSA, wherein the hub genes identified from the HMRDEGs were categorized as the model genes.Ultimately, the LASSO risk score (RiskScore) was calculated based on the risk coefficients obtained from the LASSO regression analysis. The risk score was computed using the following formula:

Validation of the diagnostic model for obstructive sleep apnea

First, the R package pROC19 (Version 1.18.5) was employed to generate ROC curves and calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for both the training dataset (GSE135917) and the external validation dataset (GSE38792).The AUC was used to assess the diagnostic accuracy of the RiskScore. A Nomogram27 is a graphical representation that employs a series of separate line segments to depict the functional association among several independent variables within a rectangular coordinate system. The R package rms (Version 6.7-1) was employed to construct a Nomogram derived from the findings of Logistic regression analysis, illustrating the interconnections among Model Genes.A calibration curve was created to evaluate the precision and resolution of the diagnostic model for OSA, using results obtained from LASSO regression analysis.The R package ggDCA (Version 1.1) was employed to generate decision curve analysis (DCA) maps based on the model genes28 in datasets GSE135917 and GSE38792.Decision curve analysis (DCA) is a simple yet effective method for evaluating clinical prediction models, diagnostic tests, and molecular indicators.

Friends analysis

The semantic analysis of Gene Ontology (GO)20 annotations offers a quantitative approach to assess the similarity among genes and genomes, establishing a crucial foundation for various bioinformatics analytical techniques.Functional similarity (Friends) analysis of Model Genes was performed by R package GOSemSim29 (Version 2.28.0).

Correlation analysis

In order to gain deeper insights into the interactions among Model Genes, the Spearman correlation coefficient was utilized to assess the expression levels of these genes in the GSE135917 dataset.The outcomes of this correlation analysis were visualized using the R package pheatmap (Version 1.0.12), which facilitated the creation of a correlation heatmap. Subsequently, the Model Genes demonstrating the highest correlation were identified and illustrated through the R package ggplot2 (Version 3.4.4), enabling the construction of a correlation scatter plot. In this analysis, an absolute correlation coefficient below 0.3 indicated weak or negligible correlation, values between 0.3 and 0.5 represented weak correlation, coefficients ranging from 0.5 to 0.8 denoted moderate correlation, while coefficients exceeding 0.8 were indicative of strong correlation.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA)30 is used to assess the distribution pattern of genes within a specified gene set, utilizing a gene table that is organized according to its correlation with a particular phenotype. This approach facilitates the determination of the genes’ contributions to the observed phenotype.In the present investigation, the genes from the GSE135917 dataset were initially prioritized based on their logFC values, contrasting the OSA group with the Control group. Subsequently, the R package clusterProfiler (Version 4.10.0) was employed to conduct GSEA on the entirety of the genes within the GSE135917 dataset. The parameters established for the GSEA included: a seed value of 2024, a minimum of 10 genes, and a maximum of 500 genes per gene set. Utilizing the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) facilitated the application of the c2.all.v2023.2.hs.symbols gene set in the enrichment analysis. The parameters established for the GSEA included an adjusted p-value threshold of less than 0.05 and a false discovery rate (FDR) value (q value) of less than 0.25, with the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method employed for p-value adjustment.

In the GSE135917 dataset, the OSA samples were classified into two distinct categories: the High-Risk group and the Low-Risk group, determined by the median value obtained from the LASSO RiskScore. Following this classification, a differential analysis was performed using the limma package in R. A threshold was established, wherein DEGs were identified with criteria of |logFC| > 0.5 and adj.p < 0.05. Specifically, genes exhibiting logFC > 0.5 and adj.p < 0.05 were classified as up-regulated DEGs, while those demonstrating logFC < -0.5 and adj.p < 0.05 were categorized as down-regulated DEGs. The results from the differential analysis were subsequently utilized to create a volcano plot employing the ggplot2 package in R. Furthermore, a heatmap was generated using the pheatmap package, focusing on the top 20 DEGs ranked by their descending |logFC| values.

Subsequently, genes derived from the OSA sample within the GSE135917 dataset were ranked according to the logFC values identified between the High-Risk and Low-Risk cohorts. Following this, the R package clusterProfiler was utilized to perform GSEA on the complete set of genes included in the GSE135917 dataset. For the GSEA execution, a seed value of 2020 was established, permitting a range of 10 to 500 genes per gene set.The c2 gene sets were obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB), specifically from the All.V2023.2.Hs.Symbols version, to facilitate GSEA. The criteria for screening in GSEA were established to encompass an adjusted p-value (adj.p) of less than 0.05, alongside a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold (q value) of less than 0.25. For the adjustment of p-values, the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) procedure was employed.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

Gene Set Variation Analysis (GSVA)31 is an unsupervised, non-parametric analytical approach utilized to assess the enrichment of gene sets within microarray-derived nuclear transcriptome data. This method involves transforming the gene expression matrix across various samples into a gene expression matrix that facilitates comparison between these samples. In order to assess the enrichment of various pathways across distinct samples, the c2.cp.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set was obtained from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)32and the R package GSVA (Version 1.50.0) was used to perform GSVA on all genes in the dataset GSE135917. The functional enrichment differences were calculated between the OSA group and the control group in the dataset GSE135917, as well as between the high-risk (HighRisk) group and the low-risk (LowRisk) group within the OSA samples. The screening criteria for GSVA were set at adj.p < 0.05, with the adj.p adjustment method being Benjamini-Hochberg (BH).

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and hub gene screening

Protein–protein interactions (PPIs) are essential for a variety of cellular functions, including signal transduction, transcriptional regulation, and metabolic control. To explore the regulatory relationships among the HMRDEGs, a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/), with the minimum required interaction score set to 0.150. This threshold enabled the identification of low-confidence but potentially meaningful interactions relevant to OSA pathogenesis.

The GeneMANIA database33 (https://genemania.org/) serves as a tool for formulating hypotheses regarding gene functionality, scrutinizing lists of genes, and prioritizing specific genes for detailed functional assessment. When provided with a set of query genes, GeneMANIA identifies genes that exhibit functional similarities by leveraging an extensive array of genomics and proteomics datasets. In this context, the database assigns weights to each functional genomic dataset based on the anticipated significance of the query. Additionally, GeneMANIA is employed for the prediction of gene functions. For any given query gene, it identifies other genes that are likely to possess shared functional attributes, contingent upon the interactions that the query gene has with them.We predicted functionally similar genes of hub genes related to hypoxia and mitophagy through GeneMANIA online website to construct a PPI Network.

Construction of regulatory network

Transcription factors (TFs) regulate gene expression by binding to specific DNA sequences and modulating the transcriptional activity of their target genes. In this study, we prioritized the ChIPBase database34 (http://rna.sysu.edu.cn/chipbase/) for TF-gene regulatory analysis, owing to its integration of large-scale ChIP-seq experimental data and broad coverage of diverse TFs and their validated target genes. This choice ensured the reliability and traceability of the data and provided a robust foundation for investigating regulatory mechanisms. Based on ChIPBase results, key TFs potentially regulating the identified hub genes were retrieved, and Cytoscape software35 was used to construct and visualize the mRNA–TF regulatory network.

Moreover, microRNAs (miRNAs) are essential regulators involved in a wide range of biological and evolutionary processes. They can target multiple genes, and conversely, a single gene can be regulated by several miRNAs, forming complex post-transcriptional regulatory networks. In this study, we employed the StarBase v3.0 database36 (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/) to predict miRNA–mRNA interactions associated with the identified hub genes. StarBase was selected for its comprehensive integration of large-scale CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data, as well as its extensive coverage of RNA interaction types, including both miRNA–mRNA and miRNA–ncRNA relationships.Additionally, its latest version systematically annotates miRNA–target interactions related to human diseases, ensuring both the breadth and accuracy of prediction results. To maintain consistency and reproducibility, only StarBase was used for miRNA prediction, and no cross-validation with other databases was performed. The resulting miRNA–mRNA regulatory network was visualized using Cytoscape software.

RNA-binding Protein (RBP)37 are essential components in the regulatory mechanisms of gene expression. They significantly influence various biological processes, including RNA synthesis, alternative splicing, post-transcriptional modifications, transportation, and translation.Based on StarBase v3.0 database36 (https://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), which forecasts the hub genes of the target RBP, The mRNA-RBP Regulatory Network was visualized by Cytoscape software.

Finally, the direct and indirect drug targets of the hub genes were predicted through the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database38 (https://ctdbase.org/). The relationship between hub genes and pharmacological agents was investigated, and the mRNA-Drug Regulatory Network was depicted using Cytoscape software to finalize the establishment of the network.

Analysis of immune infiltration in high and low risk groups

CIBERSORT39employs linear support vector regression to deconvolute the transcriptomic expression matrix, facilitating the estimation of the composition and abundance of immune cells within a heterogeneous cell population. The CIBERSORT algorithm amalgamates the matrix of immune cell characteristic genes while systematically excluding data that shows an immune cell enrichment score greater than zero. The culmination of this procedure resulted in the acquisition of specific insights related to the immune cell infiltration matrix within the OSA samples extracted from the GSE135917 dataset. This facilitated the creation of a proportion bar chart, thereby enhancing visual representation. Following this, the interrelationships among the immune cells were examined utilizing the Spearman correlation method. To effectively display the results of this correlation analysis, the R package pheatmap (Version 1.0.12) was employed to generate a correlation heatmap. Furthermore, the association between Model Genes and immune cells was also assessed using the Spearman algorithm, culminating in the production of a correlation bubble plot created with the R package ggplot2 (Version 3.4.4), which adeptly illustrates the outcomes of the correlation analysis between Model Genes and immune cells.

Statistical analysis

The analytical procedures and data processing executed in this study were performed using R software (Version 4.3.0). In the absence of specific directions, the statistical significance of normally distributed variables was assessed utilizing the independent Student’s T-Test, which allows for the comparison of continuous variables across two separate groups. For variables demonstrating a non-normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U Test, commonly known as the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, was employed to evaluate differences. The Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized for comparisons involving three or more groups. Additionally, Spearman correlation analysis was executed to determine the correlation coefficients among various biomolecules. All p-values reported were two-tailed unless specified otherwise, with a significance threshold established at p < 0.05, which was deemed indicative of statistical significance.

Results

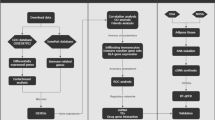

Technology roadmap

Figure 1 describes the study workflow and analysis.

Flow chart for the comprehensive analysis of HMRDEGs. OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea, GSEA Gene Set Enrichment Analysis, GSVA Gene Set Variation Analysis, DEGs Differentially Expressed Genes, HMRGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Genes, HMRDEGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Differentially Expressed Genes, GO Gene Ontology, KEGG Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, ROC Receiver Operating Characteristic, PPI Protein–protein Interaction, TF Transcription Factor, RBP RNA-Binding Protein.

Normalization of the obstructive sleep apnea dataset

The OSA datasets GSE135917 and GSE38792 were standardized and normalized by R package limma18 (Version 3.58.1). Following this, a boxplot representation of the distribution was employed to evaluate the expression levels within the GSE135917 (Fig. 2A-B) and GSE38792 (Fig. 2C-D) datasets, both prior to and subsequent to the standardization process.

Normalization of GSE135917 and GSE38792. (A) Boxplot of GSE135917 distribution in the dataset before normalization. (B) Boxplot of GSE135917 distribution of the data set after standardized processing. (C) Boxplot of GSE38792 distribution of data set before normalization. (D) Boxplot of GSE38792 distribution of data set after standardized processing. Purple is the OSA sample, and yellow is the Control sample.

Differentially expressed genes related to obstructive sleep apnea related hypoxia and mitophagy

The dataset designated as GSE135917 was categorized into two separate groups: the OSA group and the Control group. To evaluate the disparities in gene expression levels between these two classifications, the R package ‘limma’ was employed to conduct a differential analysis of the dataset. This analysis revealed a total of 2,605 differentially expressed genes(DEGs) that met the specified thresholds of |logFC| > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. Within this framework, 227 genes demonstrated up-regulation (logFC > 0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05), while 2,378 genes were found to be down-regulated (logFC < -0.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05). To effectively illustrate the differential expression results derived from this dataset, a volcano plot was subsequently created (Fig. 3A).

To identify the hypoxia and mitophagy-related differentially expressed genes (HMRDEGs), we determined the overlap among all DEGs meeting the criteria of |logFC| > 0.5 and adj.p < 0.05 alongside the hypoxia and mitochondrial autophagy-related genes (HMRGs), and subsequently illustrated this relationship using a Venn diagram (Fig. 3B).A total of 24 HMRDEGs were obtained, which were RBBP4, UCHL1, MAPK9, CLINT1, GABARAP, CAV1, SQSTM1, FLT3, NLRP3, USP33, ATP6V1A, DUSP1, CDKN2A, and HMRGS. ANXA5, MAP1LC3B, NR4A1, PPARGC1A, CLU, PLOD2, SLC2A3, GRN, TXN, DSP, MCL1.In accordance with the results derived from the intersection analysis, we examined the expression fluctuations of HMRDEGs across different sample categories within the GSE135917 dataset. To effectively illustrate the findings from the Top 20 analysis of HMRDEGs, we utilized the R package pheatmap to create a heatmap (Fig. 3C). Subsequently, we analyzed the positions of 24 HMRDEGs on the human chromosomes using the R package RCircos, resulting in the construction of a chromosome localization map (Fig. 3D). The mapping revealed that a significant proportion of HMRDEGs were situated on chromosomes 1 and 5, including RBBP4, USP33, MCL1 and NLRP3 on chromosome 1, and CLINT1, DUSP1, SQSTM1 and MAPK9 on chromosome.

Differential gene expression analysis. (A) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes analysis between OSA group and Control group in dataset GSE135917. (B) DEGs and HMRGs Venn diagram in dataset GSE135917. (C) Heat map of HMRDEGs in dataset GSE135917. (D) Chromosomal mapping of HMRDEGs. Purple is the OSA group and yellow is the Control group. In the heat map, red represents high expression and blue represents low expression. OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea, DEGs Differentially Expressed Genes, HMRGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Genes, HMRDEGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Differentially Expressed Genes.

Differential expression verification and ROC curve analysis

In order to investigate the differential expression of HMRDEGs in the GSE135917 dataset, the comparative analysis illustrated in Fig. 4A highlights the variations in expression levels of HMRDEGs between the OSA samples and the control group.The differential results showed that the expression of HMRDEGs, TXN and MCL1 in OSA samples and Control samples in GSE135917 was statistically significant (p < 0.05). In the analysis of the GSE135917 dataset, eight highly significant HMRDEGs exhibited a statistical significance level of p < 0.01 when comparing the OSA samples to the Control samples, namely: ANXA5, CLU, DSP, DUSP1, GRN, MAP1LC3B, PLOD2, SLC2A3; Fourteen HMRDEGs were highly statistically significant (p < 0.001) in OSA samples and Control samples in dataset GSE135917, namely: RBBP4, UCHL1, MAPK9, CLINT1, GABARAP, CAV1, SQSTM1, FLT3, NLRP3, USP33, ATP6V1A, CDKN2A, NR4A1, PPARGC1A. Subsequently, the R package pROC was utilized to construct the ROC curve based on the expression levels of the HMRDEGs derived from the GSE135917 dataset. The resultant ROC curve (Fig. 4B-G) demonstrated that the expression levels of ten HMRDEGs displayed remarkable accuracy (AUC > 0.9) in differentiating between samples from OSA and control subjects, respectively, which were CAV1, CDKN2A,CLINT1, FLT3, GABARAP, MAPK9, RBBP4, SQSTM1, UCHL1, USP33. The expression levels of the 14 HMRDEGs demonstrated a notable degree of accuracy (0.7 < AUC < 0.9)in distinguishing between OSA samples and control samples, which were NLRP3, ATP6V1A, DUSP1, and NLRP3, respectively. ANXA5, MAP1LC3B, NR4A1, PPARGC1A, CLU, PLOD2, SLC2A3, GRN, TXN, DSP, MCL1.

Differential expression validation and ROC curve analysis. (A) Group comparison of HMRDEGs in OSA samples and Control samples of dataset GSE135917. (B–G) Receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curves for six four-gene panels. Each panel displays the true-positive rate (TPR) against the false-positive rate (FPR), with the area under the curve (AUC) reported for every gene: (A) ANXA5, ATP6V1A, CAV1, CDKN2A; (C) CLINT1, CLU, DSP, DUSP1; (D) FLT3, GABARAP, GRN, MAP1LC3B; (E) MAPK9, MCL1, NLRP3, NR4A1; (F) PLOD2, PPARGC1A, RBBP4, SLC2A3; (G) SQSTM1, TXN, UCHL1, USP33. An AUC > 0.90 indicates high diagnostic accuracy; 0.70 ≤ AUC ≤ 0.90 indicates moderate accuracy. In the group comparison plot, yellow represents the Control group, and purple represents the OSA group. ns represents p value ≥ 0.05, no statistical significance; *p value < 0.05, statistically significant; **p value < 0.01, highly statistically significant; ***p value < 0.001 and extremely statistically significant. OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea, HMRDEGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Differentially Expressed Genes, ROC Receiver Operating Characteristic, AUC Area Under the Curve, TPR True Positive Rate, FPR False Positive Rate.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis

In order to explore the relationship between blood pressure (BP), circulating cells (CC), molecular functions (MF), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways associated with the HMRDEGs in the context of OSA, both GO and KEGG enrichment analyses were performed.The findings from the enrichment analysis of these 24 HMRDEGs are presented in Table 2. The findings indicated that the 24 HMRDEGs identified in OSA were predominantly associated with biological processes, including the cellular response to chemical stress, enhancement of proteolysis, stimulation of the ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation pathway, facilitation of the ubiquitin-mediated protein catabolism, and promotion of the proteasomal protein degradation process. CC encompass structures such as inclusion bodies, autophagosomes, and aggresomes. Meanwhile, MF include interactions with ubiquitin protein ligase, binding to ubiquitin-like protein ligase, engagement with the nuclear glucocorticoid receptor, phosphatidylethanolamine binding, and the binding of DNA transcription factors.Furthermore, these genes exhibited significant enrichment in various biological pathways as outlined by KEGG, including those associated with fluid shear stress and atherosclerosis, the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, mitophagy in animals, autophagy in animals, and Shigellosis. The outcomes of GO and KEGG enrichment analysis were represented through bubble plots for visualization purposes(Fig. 5A).

Simultaneously, the network diagrams illustrating BP, CC, MF and KEGG were created (Fig. 5B-E). The connecting lines depict the related molecules, accompanied by annotations for each corresponding entry, while the dimensions of the nodes reflect the quantity of molecules encompassed within those entries.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis for HMRDEGs. (A) The results of GO and KEGG of HMRDEGs showed that: BP, CC, MF, KEGG. GO terms and KEGG terms are shown on the abscissa. (B–E) GO and KEGG enrichment analysis results of HMRDEGs network diagram showing BP (B), CC (C), MF (D) and KEGG (E). Yellow nodes represent items, green nodes represent molecules, and the lines represent the relationship between items and molecules. The bubble size in the bubble plot represents the number of genes, and the color of the bubble represents the size of the adj. P-value, the reder the color, the smaller the adj. P-value, and the bluer the color, the larger the adj. P-value. The screening criteria for GO and KEGG enrichment analysis were adj. p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and the adj. p correction method was Benjamini-Hochberg (BH). HMRDEGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Differentially Expressed Genes, GO Gene Ontology, KEGG Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, BP Biological Process, CC Cellular Component, MF Molecular Function.

GSEA for OSA

To evaluate the influence of gene expression levels within the GSE135917 dataset on OSA, GSEA was performed to investigate the relationships between the expression profiles of all genes in this dataset and their involvement in the BP, CC and MF (Fig. 6A). The comprehensive results are detailed in Table 3. The analysis demonstrated that genes within the GSE135917 dataset were significantly enriched in specific pathways, including the metabolism of polyamines (Fig. 6B), hedgehog ligand biogenesis (Fig. 6C), and the negative regulation of Notch4 signaling (Fig. 6E), alongside other relevant biological functions and signaling pathways, such as the Auf1 Hnrnp D0 interaction with mRNA, which leads to its destabilization (Fig. 6D).

GSEA for GSE135917 between OSA group and Control group. (A) Mountain map summarising the four pathways that passed the significance threshold. For each pathway the normalised enrichment score (NES), adjusted P value (P adj) and false-discovery rate (FDR) are shown. (B–E) Running enrichment curves for the same pathways: Metabolism of Polyamines (B; NES = 2.996), Hedgehog Ligand Biogenesis (C; NES = 3.023), Auf1/Hnrnp D0 Binds and Destabilises mRNA (D; NES = 3.249) and Negative Regulation of NOTCH4 Signalling (E; NES = 3.500). The red line indicates the cumulative enrichment score across the ranked gene list; the lower barcode shows the position of leading-edge genes (red = up-regulated in OSA, blue = up-regulated in controls). The screening criteria of GSEA were adj. p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and the adj. p correction method was Benjamini-Hochberg (BH). GSEA Gene Set Enrichment Analysis.

GSVA for OSA

In order to explore the variations in the c2.cp.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set between the OSA group and the control group within the GSE135917 dataset, GSVA was carried out on the complete set of genes encompassed in this dataset. The comprehensive details are provided in Table 4. Subsequently, the top 20 pathways exhibiting adj.p < 0.05, along with the absolute values of logFC, were identified and ranked in descending order. The differential expression of these 20 pathways between the OSA group and the control group was then analyzed and represented visually through a heat map (Fig. 7A).

The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to confirm the observed differences, and the outcomes were visually represented in the group comparison chart (Fig. 7B). The GSVA results indicated that the inhibition of exosome biogenesis and secretion induced by Manumycin A in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) cells was significantly associated with several pathways. These included the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) GB to PDGFR RAS ERK signaling pathway, glutathione metabolism, epidermal growth factor (EGF) to EGFR RAS RALGDS signaling pathway, including the processes of folding, assembly, and peptide loading onto class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC). Additionally, significant interactions were observed with the Shigella pathway leading to actin signaling, the prion-like conformation of scrapie (PrPSc) in relation to 26 S proteasome-mediated protein degradation, and aberrant amyloid-beta (Aβ) and alpha-synuclein (SNCA) mutations also linked to the 26 S proteasome-mediated degradation pathway. Other noteworthy pathways included the BioCarta proteasome pathway, the formation of apoptosomes, the cytochrome c-mediated apoptotic response, and the Escherichia coli pathways mapping to CDC42 and RAC signaling. Furthermore, the analysis highlighted the relevance of COPII vesicle formation, aberrant Aβ influencing the VGCC Ca2 + apoptotic pathway (N01006), the reference to beta-oxidation, glycolysis during senescence, and aerobic glycolysis. All of these correlations exhibited statistical significance when comparing the OSA group with the control group (p value < 0.05).

GSVA analysis for GSE135917. (A, B) Heat map (A) and group comparison map (B) of GSVA results between OSA group and Control group in dataset GSE135917. ns stands for p value ≥ 0.05, not statistically significant; *p value < 0.05, statistically significant; **p value < 0.01, highly statistically significant; ***p value < 0.001 and extremely statistically significant. Purple represents the OSA group and yellow represents the Control group. The screening criteria of GSVA was adj. p < 0.05, and the correction method was Benjamini-Hochberg (BH). Blue represents low enrichment and red represents high enrichment in the heat map. OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea, GSVA Gene Set Variation Analysis.

Construction of diagnostic model for OSA

We initially assessed the diagnostic significance of 24 HMRDEGs in OSA using logistic regression analysis. The forest plot (Fig. 8A) illustrating this model indicated that all 24 genes were statistically significant (p < 0.05). These genes include RBBP4, UCHL1, MAPK9, CLINT1, GABARAP, CAV1, SQSTM1, FLT3, NLRP3, USP33, ATP6V1A, DUSP1, CDKN2A, ANXA5, MAP1LC3B, NR4A1, PPARGC1A, CLU, PLOD2, SLC2A3, GRN, TXN, DSP, MCL1. Subsequently, we constructed a Support Vector Machine model utilizing these 24 HMRDEGs combined with the SVM algorithm. Analysis of the number of genes associated with the lowest error rate (Fig. 8B) and the highest accuracy rate (Fig. 8C) revealed that the model performed optimally when using 10 genes.To optimize diagnostic efficacy, we employed LASSO regression analysis to further screen the aforementioned 10 genes. A regression model plot (Fig. 8D) and a variable trajectory plot (Fig. 8E) were generated to enhance visualization. Ultimately, four key genes – NLRP3, MAPK9, RBBP4, and CLINT1 – were incorporated into the LASSO regression model as model genes.Ultimately, based on the risk coefficients obtained from the LASSO regression analysis, we calculated the final LASSO risk score (RiskScore). The calculation formula is described below:

Diagnostic model of OSA. (A) Forest Plot of 24 HMRDEGs included in the Logistic regression model in the diagnostic model of OSA. (B, C) The number of genes with the lowest error rate (B) and the number of genes with the highest accuracy (C) obtained by the SVM algorithm are visualized. (D, E) Diagnostic model plot (D) and variable trajectory plot (E) of LASSO regression model. OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea, HMRDEGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Differentially Expressed Genes, SVM Support Vector Machine, LASSO Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator.

Internal validation and friends analysis of the diagnostic model for OSA

Initially, the R package pROC was utilized to construct the ROC curve based on the RiskScore obtained from the GSE135917 dataset. As illustrated in Fig. 9A, the ROC curve based on the RiskScore in the GSE135917 dataset (training set) showed a high diagnostic accuracy, with an AUC of 0.982, indicating excellent discriminatory ability between OSA and control samples. This performance supports the robustness of the model in identifying high-risk individuals within the training cohort.

Diagnostic and validation of GSE135917 and friends analysis. (A) ROC curve of RiskScore in dataset GSE135917. (B) Nomogram of Model Genes in dataset GSE135917 in OSA diagnostic model. (C, D) Calibration Curve plot (C) and decision curve analysis (DCA) plot (D) of the OSA diagnostic Model based on the Model Genes in dataset GSE135917. (E) Box plot of functional similarity (Friends) analysis results of Model Genes. The ordinate of the decision curve analysis (DCA) plot is the net benefit, and the abscissa is the Probability Threshold or Threshold Probability. The AUC of the ROC curve is generally between 0.5 and 1. The closer the AUC is to 1, the better the diagnostic performance. High accuracy is achieved when AUC is above 0.9. ROC Receiver Operating Characteristic, AUC Area Under the Curve, DCA Decision Curve Analysis, TPR True Positive Rate, FPR False Positive Rate.

To further validate the diagnostic value of the model for OSA, a nomogram was constructed utilizing the model genes to illustrate the interrelationship among these genes within the dataset GSE135917 (Fig. 9B).The findings indicated that the significance of CLINT1 expression within the diagnostic framework for OSA was markedly superior to that of other examined variables. Conversely, the importance of MAPK9 in the OSA diagnostic model was found to be considerably inferior compared to the other variables.

In order to assess the accuracy and resolution of the diagnostic model for OSA, a Calibration Curve was constructed through Calibration analysis. The model’s predictive efficacy in relation to actual outcomes was evaluated by investigating the correspondence between the predicted probabilities and the actual probabilities across various scenarios, as depicted in Fig. 9C. The Calibration Curve pertaining to the OSA diagnostic model reveals that the calibration line, illustrated by the dotted line, shows a certain degree of deviation from the ideal diagonal line of the model. Additionally, a decision curve analysis (DCA) was conducted to evaluate the clinical relevance of the OSA diagnostic model, employing the model genes derived from the GSE135917 dataset, with the results presented in Fig. 9D. The results indicated that the performance line of the model consistently surpassed both the All Positive and All Negative lines within a defined range, signifying a higher net benefit associated with the model and thereby implying its superior effectiveness.

Ultimately, the outcomes of the functional similarity assessment (Friends) were utilized to identify genes that are significant contributors to the biological processes associated with OSA (Fig. 9E). The findings indicated that CLINT1 emerged as a key player in OSA, being the gene that closely approached the designated critical threshold (cut-off value = 0.62).

External validation and friends analysis of the diagnostic model for obstructive sleep apnea

First, the R package pROC was employed to generate the ROC curve utilizing the RiskScore derived from the GSE38792 dataset. As shown in Fig. 10A, the ROC curve analysis of the diagnostic model in the GSE38792 dataset (external validation set) yielded an AUC of 0.812, reflecting moderate to good diagnostic performance. Although slightly lower than the training set, this result demonstrates the model’s generalizability and external validity across independent datasets.

Diagnostic and validation of GSE38792 and friends analysis. (A) ROC curve of RiskScore in dataset GSE38792. (B) Nomogram of Model Genes in dataset GSE38792 in OSA diagnostic model. (C, D) Calibration Curve plot (C) and decision curve analysis (DCA) plot (D) of OSA diagnostic Model based on Model Genes in dataset GSE38792. (E) Boxplot of functional similarity (Friends) analysis results of Model Genes. The ordinate of the decision curve analysis (DCA) plot is the net benefit, and the abscissa is the Probability Threshold or Threshold Probability. The AUC of the ROC curve is generally between 0.5 and 1. The closer the AUC is to 1, the better the diagnostic performance. The AUC had some accuracy between 0.7 and 0.9. ROC Receiver Operating Characteristic, AUC Area Under the Curve, DCA Decision Curve Analysis, TPR True Positive Rate, FPR False Positive Rate.

To enhance the validation of the diagnostic model for OSA, a nomogram was constructed utilizing the model genes. This graphical representation illustrates the interconnections among the model genes within the dataset GSE38792 (Fig. 10B).The findings indicated that the effectiveness of the Model Gene RBBP4 within the diagnostic framework for OSA was considerably greater compared to other factors. In contrast, the significance of NLRP3 expression within the diagnostic framework for OSA was considerably lower compared to the other factors involved.

To assess the accuracy and resolution of the OSA diagnostic model, a Calibration Curve was created through comprehensive calibration analysis. The model’s predictive performance was evaluated by comparing the actual probabilities with the predicted ones across various scenarios, as shown in Fig. 10C. The Calibration Curve for the OSA diagnostic model reveals a slight divergence of the calibration line, represented by the dotted line, from the ideal diagonal line. To establish the clinical significance of this OSA diagnostic model, a decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed using gene data from the GSE38792 dataset, with the findings illustrated in Fig. 10D. The results of this analysis demonstrated that the model’s performance consistently surpassed both the “All positive” and “All negative” lines within a specific range, underscoring a notable net benefit associated with the model.

In conclusion, the Friends analysis was utilized to pinpoint the genes that play a crucial role in the biological mechanisms linked to OSA (Fig. 10E). The results revealed that CLINT1 is notably implicated in OSA, being identified as the gene that is closest to the significant threshold (cut-off value = 0.62).

Correlation analysis of model genes

Correlation analysis was conducted utilizing the expression levels of four Model Genes within the OSA samples from the GSE135917 dataset, a correlation heatmap (Fig. 11A) was created to visually depict the findings. Furthermore, the outcomes of the correlation analysis, particularly focusing on the genes exhibiting the most significant correlations as depicted in the heatmap, were illustrated through correlation scatter plots (Fig. 11B-C). RBBP4 and CLINT1 showed the strongest significant positive correlation (r value = 0.629, p value < 0.05), and NLRP3 and RBBP4 showed the strongest significant negative correlation (r value = -0.418, P value < 0.05). p value < 0.05).

Correlation analysis of model genes. (A) Correlation heatmap of Model Genes. (B) Scatter plot of the correlation between Model Genes RBBP4 and CLINT1. (C) Scatter plot of the correlation between Model Genes NLRP3 and RBBP4. The absolute value of correlation coefficient below 0.3 was weak or no correlation, 0.3–0.5 was weak correlation, and 0.5–0.8 was moderate correlation. Red is a positive correlation, blue is a negative correlation, and the depth of color represents the strength of the correlation. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

GSEA for high and low risk groups

In order to perform a more detailed differential analysis of OSA samples within the GSE135917 dataset, the dataset was categorized into High-Risk and Low-Risk groups based on the median LASSO RiskScore obtained from the OSA model. The R package limma was then utilized to carry out a differential expression analysis on GSE135917, thereby allowing for the detection of genes that demonstrate significant expression variances between the two specified groups. The results are encapsulated as follows: within the dataset GSE135917, a total of 551 DEGs were identified that satisfied the criteria of |logFC| > 0.5 and adj.p < 0.05. Among these, there were 45 genes exhibiting upregulation (logFC > 0.5 and adj.p < 0.05), while the remaining 506 genes displayed downregulation (logFC < 0.5 and adj.p < 0.05).Based on the findings from the differential analysis of the dataset, a volcano plot was generated (Fig. 12A). Utilizing the differential analysis results, the top 20 DEGs were identified and arranged in descending order of |logFC|. Subsequently, a heatmap was constructed employing the R package pheatmap to illustrate these analytical results (Fig. 12B).

Differential gene expression analysis and GSEA for risk groups. (A, B) Volcano map (A) and heat map (B) of differentially expressed genes analysis between HighRisk group and LowRisk group in dataset GSE135917. (C) GSEA of dataset GSE135917 showed 4 biological functions in mountain map. (D–G) GSEA showed that dataset GSE135917 was significantly enriched in Reactome Regulation Of Pten Stability And Activity (D). Reactome Negative Regulation Of Notch4 Signaling (E), Reactome Auf1 Hnrnp D0 Binds And Destabilizes Mrna (F), Bystroem Correlated With Il5 Dn (G). OSA Obstructive Sleep Apnea, GSEA Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Blue represents the high risk (HighRisk) group and pink represents the low risk (LowRisk) group. In the mountain plot, the color represents the NES value, the more red the color is, the greater the NES value, and the more blue the color is, the smaller the NES value. In the heat map, red represents high expression and blue represents low expression. The screening criteria of gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) were adj. p < 0.05 and FDR value (q value) < 0.25, and the adj. p correction method was Benjamini-Hochberg (BH).

To assess the influence of gene expression levels within the dataset GSE135917 on the development of OSA, we utilized GSEA to analyze the log fold change (logFC) values of all genes between the High Risk and Low Risk groups. The objective of this methodology was to clarify the relationship between the expression levels of these genes and their roles in BP, CC and MF. The findings were visually represented in a mountain plot (Fig. 12C), with comprehensive results detailed in Table 5.The findings indicated that every gene within the GSE135917 dataset exhibited substantial enrichment in the Reactome pathway associated with the Regulation of PTEN Stability and Activity (Fig. 12D). Additionally, all genes from the GSE135917 dataset demonstrated significant enrichment in the Reactome pathways pertaining to the Negative Regulation of Notch4 Signaling (Fig. 12E), the binding and destabilization of mRNA by Auf1 and Hnrnp D0 (Fig. 12F), as well as a correlation between Bystroem and IL5 Dn (Fig. 12G), alongside various other biologically relevant functions and signaling pathways.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA) for high and low risk groups

To investigate the disparities in the c2.cp.v2023.2.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set between the high-risk (HighRisk) cohort and the low-risk (LowRisk) cohort within the GSE135917 dataset, GSVA was conducted on the entirety of the genes present in this dataset. Comprehensive details regarding this analysis are provided in Table 6. Subsequently, the top 20 pathways exhibiting adj.p < 0.05 and a descending order of absolute log fold change (logFC) were selected for analysis. The differential expression of these 20 pathways was examined and depicted using a heat map to illustrate the contrasts between the High-Risk group and the Low-Risk group (Fig. 13A).

Subsequently, the distinction was confirmed utilizing the Mann-Whitney U test, and a comparative analysis diagram (Fig. 13B) was created to illustrate the findings.The GSVA results revealed that several pathways, including the Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle, the deficiency of the Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex (PDHC), isoleucine degradation, proteasome degradation, and the destabilization of mRNA by AUF1 HNRNP D0, demonstrated statistical significance between the High-Risk and Low-Risk groups (p < 0.05). Additional pathways of note included the MEDICUS variant scrapie conformation, which is associated with 26 S proteasome-mediated protein degradation, as well as mutations leading to aberrant forms of Aβ and SOD1, both linked to the same proteasomal degradation process. Furthermore, the inhibition of exosome biogenesis and secretion via Manumycin A in CRPC cells, platelet sensitization by LDL, cristae formation, the TCA cycle (also known as the Krebs or citric acid cycle), and the formation of the apoptosome were also statistically significant. The cytochrome C-mediated apoptotic response and MASTL activity in mitotic progression, along with MEDICUS reference for COPII vesicle formation, inhibition of damaged DNA replication initiation by RB1 E2F1, and antigen presentation via class I MHC folding and peptide loading, as well as the BioCarta EIF pathway and TGF SMAD signaling pathway, were likewise found to differ significantly between the two groups (p < 0.05).

GSVA analysis for risk groups. (A, B) Heat map (A) and group comparison map (B) of GSVA results between HighRisk group and LowRisk group of dataset GSE135917. GSVA, Gene Set Variation Analysis. ns stands for p value ≥ 0.05, not statistically significant; *p value < 0.05, statistically significant; **p value < 0.01, highly statistically significant; ***p value < 0.001 and highly statistically significant. Blue represents the HighRisk group, pink represents the LowRisk group. The screening criteria of gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was adj. p < 0.05, and the adj. p correction method was Benjamini-Hochberg (BH). Blue represents low enrichment and red represents high enrichment in the heat map.

Construction of protein-protein interaction network and screening of hub genes

The constructed network revealed direct connections among three model genes—RBBP4, MAPK9, and NLRP3—which were subsequently recognized as potential hub genes (Fig. 14A). These genes were selected based on their interactive relationships within the STRING network, rather than explicit centrality metrics such as degree, betweenness, or closeness. While these interaction-based criteria provide initial insight into network topology, we acknowledge that incorporating quantitative centrality-based metrics would enhance the robustness of hub gene identification. As such, we plan to integrate Cytoscape’s CytoHubba plugin in future studies to systematically prioritize hub genes using standardized network measures.

To further explore functional associations, we employed the GeneMANIA platform to predict and expand the interaction network involving these three candidate hub genes and additional functionally similar genes (Fig. 14B). The resulting network includes 20 related proteins, with the edges indicating types of relationships such as co-expression, physical interaction, and shared protein domains. These findings provide additional support for the biological relevance of RBBP4, MAPK9, and NLRP3 in the context of OSA.

PPI network and hub genes analysis. (A) Protein-protein interaction Network (PPI Network) of Model Genes calculated by STRING database. (B) The interaction network of genes with similar functions predicted by GeneMANIA website. The circles in the figure show the hub genes related to hypoxia and mitophagy and the genes with similar functions. The colors corresponding to the lines represent the interconnected functions. PPI Network Protein–protein Interaction Network.

Construction of regulatory network

Initially, the transcription factor (TF) associated with the hub genes were extracted from the ChIPBase database. Subsequently, an mRNA-TF regulatory network was established and depicted using Cytoscape software (Fig. 15A). This examination revealed a total of 3 hub genes and 40 TF, with comprehensive details available in Table S2.

Regulatory Network of hub genes. (A) mRNA-TF Regulatory Network of hub genes. (B) mRNA-miRNA Regulatory Network of hub genes. (C) mRNA-RBP Regulatory Network of hub genes. D. mRNA-Drug Regulatory Network of hub genes. HMRGs Hypoxia and Mitophagy-Related Genes, TF Transcription Factor, RBP RNA-Binding Protein. Orange is mRNA, pink is TF, purple is miRNA, blue is RBP, and green is Drug.

Following this, the microRNAs linked to the hub genes were extracted from the StarBase database. This process facilitated the development and visualization of the mRNA-miRNA Regulatory Network, which was accomplished utilizing Cytoscape software(Fig. 15B). This analysis identified 2 hub genes along with 38 miRNAs, with detailed information provided in Table S3.

Then, the RNA-binding proteins (RBP) linked to the hub genes were identified utilizing the StarBase database. Following this, a regulatory network comprising mRNA-RBP interactions was established and visualized using Cytoscape software, as illustrated in Fig. 15C. This network included two hub genes and a total of 41 RBP, with detailed information provided in Table S4.

In summary, potential pharmacological compounds or molecular entities associated with the pivotal genes were identified through the CTD. Subsequently, the mRNA-Drug Regulatory Network was developed and visualized utilizing Cytoscape software (Fig. 15D). This network comprises 3 central genes alongside 39 pharmacological agents or molecular compounds, with detailed information available in Table S5.

Immune infiltration analysis of high and low risk groups (CIBERSORT)

The GSE135917 dataset was employed to evaluate the prevalence of immune cell infiltration across 22 distinct immune cell types by leveraging the CIBERSORT algorithm. Initially, a bar chart was created to depict the distribution of immune cells within the GSE135917 dataset (Fig. 16A), reflecting the results obtained from the immune infiltration analysis.The findings indicated that a total of 18 distinct immune cell types exhibited significant enrichment in samples derived from individuals with OSA. The study investigated various immune cell populations, which included naive B cells, memory B cells, plasma cells, CD8 T cells, resting memory CD4 T cells, follicular helper T cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), both resting and activated natural killer (NK) cells, monocytes, M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, resting and activated dendritic cells, resting mast cells, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Subsequently, a correlation heat map was employed to depict the associations between immune cell infiltration levels within the OSA samples (Fig. 16B-C). The results revealed that most immune cell types in the LowRisk cohort displayed strong correlations, with Monocytes and M0 Macrophages exhibiting the most significant negative correlation (r = -0.828, P < 0.05) (Fig. 16B).In contrast, within the High-Risk cohort, a majority of immune cell types exhibited robust correlations, with CD4 memory resting T cells and activated NK cells demonstrating the most substantial positive correlation (r = 0.776, P < 0.05) as depicted in Fig. 16C. Additionally, the associations between model genes and the levels of immune cell infiltration were represented through correlation bubble plots (Fig. 16D-E). The information depicted in these figures indicates that a substantial proportion of immune cells within the Low-Risk category of OSA samples displayed robust correlations. Notably, the gene demonstrated the most pronounced positive correlation with activated dendritic cells, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.843 and a significance level of P < 0.05, as illustrated in Fig. 16D. Conversely, within the High-Risk group, many immune cell types also displayed strong correlations; notably, a significant negative correlation was identified between the RBBP4 gene and M0 macrophages (r = -0.529, P < 0.05)(Fig. 16E).

Risk groups immune infiltration analysis by CIBERSORT Algorithm. (A) Bar chart of the proportion of immune cells in OSA samples. (B, C) Correlation heatmap of immune cells in the LowRisk (B) and HighRisk (C) groups of OSA samples. (D, E) Bubble plot of correlation between immune cell infiltration abundance and Model Genes in the LowRisk (D) and HighRisk (E) groups of OSA samples. The absolute value of correlation coefficient (r value) below 0.3 was weak or no correlation, between 0.3 and 0.5 was weak correlation, between 0.5 and 0.8 was moderate correlation, and above 0.8 was strong correlation. Pink is the LowRisk group, blue is the HighRisk group. Red is the positive correlation, blue is the negative correlation. The depth of the color represents the strength of the correlation.

Discussion

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a prevalent disorder characterized by recurrent upper-airway obstruction that disrupts sleep architecture and causes daytime dysfunction. OSA confers an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease—including hypertension, arrhythmia, and heart failure—underscoring the need for deeper molecular insight. In this study, we identified 24 hypoxia-and mitophagy-related differentially expressed genes (HMRDEGs) that were significantly dysregulated in OSA versus control samples. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis confirmed their diagnostic value, and Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG enrichment linked them to autophagy and cellular stress pathways. These findings refine our understanding of OSA pathogenesis and lay the groundwork for diagnostic models and targeted therapies focused on key HMRDEGs.

The 24 HMRDEGs identified in this study—particularly RBBP4, UCHL1, and MAPK9—illuminate key molecular mechanisms in OSA. RBBP4, a retinoblastoma-binding protein that regulates the cell cycle and apoptosis40,interacts with hypoxia-inducible factors, thereby shaping the cellular response to low oxygen levels41.Its dysregulation may thus contribute to the hypoxia-driven pathology of OSA. UCHL1, a ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase essential for proteostasis, also modulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy42,43. The elevated UCHL1 expression observed here could represent a compensatory reaction to OSA-induced mitochondrial stress, making it a promising therapeutic target.MAPK9 (JNK2) governs stress-activated signaling, inflammation, and apoptosis and is implicated in cancer and neurodegeneration44. Its differential expression in our dataset suggests a role in the inflammatory cascades associated with OSA. Because gene-expression patterns may vary across ethnicities, population-specific studies are warranted to validate these candidates as biomarkers and to clarify their contributions to disease progression.

HMRDEGs are significantly enriched in pathways governing protein degradation and autophagy, underscoring the intricate stress-response and metabolic networks that may drive OSA. The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS), a core proteostatic pathway, eliminates misfolded or damaged proteins to maintain cellular homeostasis. Disruption of the UPS has been implicated in several disorders, including OSA. Inadequate protein clearance can promote toxic protein accumulation, escalate cellular stress, and amplify inflammation—hallmarks of OSA pathology. These observations align with growing evidence that proteostasis is central to disease progression and suggest that therapies aimed at restoring UPS function could be clinically beneficial.

Autophagy maintains cellular integrity and energy balance by clearing damaged organelles and proteins, thereby limiting oxidative stress and inflammation45,46. The marked enrichment of HMRDEGs in autophagy-related modules implies that impaired autophagic flux is a central mechanism by which OSA disrupts cellular homeostasis. Therapeutic strategies that restore or modulate autophagy could thus offer new avenues for treating OSA, especially in patients with significant metabolic dysregulation.

It is important to recognise that the discovery cohort (GSE135917) originates from subcutaneous adipose tissue, whereas the validation cohort (GSE38792) was generated from visceral fat. These depots differ markedly in lipid metabolism, inflammatory tone, and transcriptomic architecture47,48,49. For example, Visceral adipocytes express higher basal levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and hypoxia-inducible genes, whereas subcutaneous fat is enriched for extracellular-matrix remodeling and thermogenic pathways. Such depot-specific signatures can bias differential-expression analyses, pathway enrichment, and immune-cell deconvolution. Accordingly, associations between the four-gene RiskScore and disease severity should be interpreted with caution, as they may primarily reflect depot-specific biology. Paired visceral and subcutaneous samples—or single-cell datasets—are needed to disentangle tissue-restricted from systemic OSA effects.

Finally, pinpointing critical regulatory hubs sheds light on OSA progression. Central sensors such as mTOR and AMPK orchestrate autophagy and proteostasis, and their activity may reflect disease severity50,51. Deciphering how these nodes modulate cellular responses to intermittent hypoxia will facilitate the design of targeted therapies. Harnessing pathway-enrichment insights could therefore enable more precise OSA management and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

CIBERSORT deconvolution identified 18 immune-cell subsets in OSA samples, with the most pronounced shifts in monocytes and macrophages.Monocytes—the precursors of macrophages—coordinate innate immunity, particularly under inflammatory stress52.After recruitment to tissue, they polarize into classically activated (M1) or alternatively activated (M2) macrophages, which respectively exacerbate or resolve inflammation. Clarifying this monocyte–macrophage axis in OSA could reveal strategies to skew polarization toward an M2-like phenotype, thereby dampening inflammation and promoting tissue repair.

Recent evidence highlights immune dysregulation as a key driver of OSA. Patients with OSA show a skewed monocyte landscape, notably higher proportions of intermediate and non-classical subsets, which promote systemic inflammation53. The Th17/Treg balance is likewise disrupted, amplifying inflammatory signalling and accelerating disease progression54. Intermittent hypoxia activates the TLR4-MyD88-NF-κB pathway and the NLRP3 inflammasome, triggering release of IL-1βand IL-1854. These immune disturbances propagate beyond the airway, contributing to the cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities common in OSA.Therapies that dampen pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages or boost anti-inflammatory M2 populations could therefore help curb chronic inflammation and its sequelae55. A nuanced understanding of how distinct immune-cell profiles interact with the hypoxic microenvironment of OSA will be crucial for developing targeted interventions.

The LASSO model built on NLRP3, MAPK9, RBBP4, and CLINT1 achieved an AUC > 0.90, demonstrating excellent discrimination of high-risk OSA. This result sets a performance benchmark for future diagnostic tools. To enhance clinical utility, the model should be validated in larger, diverse cohorts that include comorbidities, demographic variables, and lifestyle factors. Incorporating these data will improve generalizability and support real-world implementation.

The Comparative Toxicogenomics Database (CTD) associates 39 small molecules with our hub genes, highlighting their therapeutic promise in OSA. Notably, NLRP3 and MAPK9 regulate inflammation and oxidative stress—central drivers of OSA pathophysiology. Selective inhibitors such as MCC950 (NLRP3) and SP600125 (MAPK9) have already reduced inflammatory signaling and cellular stress in preclinical models56,57.These findings position hub-gene-targeted pharmacology as a promising strategy for both single-agent and combination therapies in OSA.

We combined STRING connectivity with quantitative centrality scores and confirmed that RBBP4, MAPK9, and NLRP3 are topological “hot spots”in the OSA interactome, displaying high degree and betweenness. Although this dual-metric strategy reduces the bias of single-index selection, incorporating additional measures—such as closeness, eigenvector, and maximal-clique centrality—could further refine hub prioritization. Future work will apply the full CytoHubba suite and machine-learning-based network analyses, integrate multi-omics data, and leverage larger patient cohorts to produce a more systematic and standardized hub-gene ranking.

The network-level overlap between OSA and lung cancer reported by Dasgupta et al.4 lends external support to our hypoxia-driven HMRDEG signature: two of our hub genes, NLRP3 and MAPK9, are established modulators of tumour-related inflammation and epithelial responses, underscoring the translational promise of targeting hypoxia–mitophagy–immune axes across hypoxic diseases.In the present study we analysed two independent RNA-seq cohorts (GSE135917, GSE38792) and built a four-gene diagnostic model that achieved excellent discrimination in both the discovery set (AUC = 0.982) and an external validation set (AUC = 0.812), thereby expanding the molecular understanding of OSA and highlighting actionable therapeutic targets.

Several limitations warrant attention. First, reliance on publicly available datasets with modest sample sizes introduces heterogeneity and potential selection bias. Second, our findings are based solely on in-silico analyses; qPCR, Western blot, and functional assays in chronic intermittent hypoxia models are essential to confirm gene expression and causality. Finally, large multicentre prospective cohorts that integrate multi-omics layers are needed to validate and refine the model, accelerate biomarker discovery, and facilitate clinical translation.

Data availability

The authors state that the data underlying the findings of this study are provided in the article and the Supplementary Information. Bulk RNA-Seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository under accession number GSE135917 and GSE38792. Additional data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Benjafield, A. V. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence and burden of obstructive sleep apnoea: a literature-based analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 7, 687–698 (2019).

Musso, G. et al. Association of obstructive sleep Apnoea with the presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 14, 417–431 (2013).

Meurice, J. C., Antone, E., Gilbert, M., Watrin, A. & Bironneau, V. [Continuous positive airway pressure in obstructive sleep apnea]. Presse Med. 46, 423–431 (2017).

Dasgupta, S. Identification of overlapping genetic signatures between obstructive sleep apnea and lung cancer: moving beyond one drug, one disease paradigm of pharmaceutical innovation. OMICS: J. Integr. Biology. 29, 221–228 (2025).

Zhou, E. et al. Identifying and validating immunological biomarkers in obstructive sleep apnea through bioinformatics analysis. Sci. Rep. 15, 9746 (2025).

Davis, S. & Meltzer, P. S. GEOquery: a Bridge between the gene expression omnibus (GEO) and bioconductor. Bioinformatics 23, 1846–1847 (2007).

Obstructive sleep apnea. And CPAP therapy alter distinct transcriptional programs in subcutaneous fat tissue - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31872261/

Gharib, S. A., Hayes, A. L., Rosen, M. J. & Patel, S. R. A pathway-based analysis on the effects of obstructive sleep apnea in modulating visceral fat transcriptome. Sleep 36, 23–30 (2013).

NCBI GEO. archive for functional genomics data sets–update - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23193258/

Stelzer, G. et al. The genecards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 54, 1301–13033 (2016).

Mo, Z. et al. Identification of a Hypoxia-Associated signature for lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Genet. 11, 647 (2020).

Zhang, Q. et al. Integrative analysis of Hypoxia-Associated signature in Pan-Cancer. iScience 23, 101460 (2020).

Fu, Y. et al. Development and validation of a Hypoxia-Associated prognostic signature related to osteosarcoma metastasis and immune infiltration. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 633607 (2021).

Zhuo, Z. et al. Mitophagy-Related gene signature for prediction prognosis, immune scenery, mutation, and chemotherapy response in pancreatic cancer. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 802528 (2021).

Wang, Y., Wang, Z., Sun, J. & Qian, Y. Identification of HCC subtypes with different prognosis and metabolic patterns based on mitophagy. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 799507 (2021).

Xu, W. et al. The prognostic value and clinical significance of mitophagy-related genes in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Genet. 13, 917584 (2022).

Zhang, H., Sun, H., Zhang, W., Xu, Y. & Geng, D. Identification of key genes and potential mechanisms based on the autophagy regulatory network in osteoclasts using a murine osteoarthritis model. J. Inflamm. Res. 15, 2333–2347 (2022).

limma powers differential. expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25605792/

Robin, X. et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S + to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Mi, H., Muruganujan, A., Ebert, D., Huang, X. & Thomas, P. D. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D419–D426 (2019).

KEGG. kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10592173/

Kanehisa, M. Toward Understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y. & Kawashima, M. Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Yu, G., Wang, L. G., Han, Y. & He, Q. Y. ClusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS 16, 284–287 (2012).

Sanz, H., Valim, C., Vegas, E., Oller, J. M. & Reverter, F. SVM-RFE: selection and visualization of the most relevant features through non-linear kernels. BMC Bioinform. 19, 432 (2018).

Statistical predictions with glmnet - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31443682/

Wu, J. et al. A nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma: A population-based analysis. Cancer Commun. (Lond). 40, 301–312 (2020).

Van Calster, B. et al. Reporting and interpreting decision curve analysis: A guide for investigators. Eur. Urol. 74, 796–804 (2018).

Yu, G. et al. GOSemSim: an R package for measuring semantic similarity among GO terms and gene products. Bioinformatics 26, 976–978 (2010).

Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 102, 15545–15550 (2005).

GSVA. gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23323831/

Liberzon, A. et al. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics 27, 1739–1740 (2011).

Franz, M. et al. GeneMANIA update 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W60–W64 (2018).

Zhou, K. R. et al. ChIPBase v2.0: decoding transcriptional regulatory networks of non-coding RNAs and protein-coding genes from ChIP-seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D43–D50 (2017).

Cytoscape. a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14597658/

Li, J. H., Liu, S., Zhou, H., Qu, L. H. & Yang, J. H. StarBase v2.0: decoding miRNA-ceRNA, miRNA-ncRNA and protein-RNA interaction networks from large-scale CLIP-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D92–97 (2014).

RNA-binding protein kinetics - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33828270/

Grondin, C. J. et al. Predicting molecular mechanisms, pathways, and health outcomes induced by Juul e-cigarette aerosol chemicals using the comparative toxicogenomics database. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2, 272–281 (2021).

Robust enumeration of. cell subsets from tissue expression profiles - PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25822800/

Schultz-Rogers, L. E. et al. Rbbp4 loss disrupts neural progenitor cell cycle regulation independent of Rb and leads to Tp53 acetylation and apoptosis. Dev. Dyn. 251, 1267–1290 (2022).

Zhan, Y. et al. Interpreting the molecular mechanisms of RBBP4/7 and their roles in human diseases (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 53, 48 (2024).

Mi, Z. & Graham, S. H. Role of UCHL1 in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases and brain injury. Ageing Res. Rev. 86, 101856 (2023).

Tangri, A. et al. Deubiquitinase UCHL1 maintains protein homeostasis through the PSMA7-APEH-Proteasome axis in High-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Res. 19, 1168–1181 (2021).

Barutcu, S. A., Girnius, N., Vernia, S. & Davis, R. J. Role of the mapk/cjun NH2-terminal kinase signaling pathway in starvation-induced autophagy. Autophagy 14, 1586–1595 (2018).

Ac, R., Sa, K., Amk, C. & Sm, C. Autophagy and inflammation in chronic respiratory disease. Autophagy 14, (2018).

Ding, H., Guo, H. & Cao, J. The importance of autophagy regulation in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. Breath. 25, 1211–1218 (2021).

Kahn, C. R., Wang, G. & Lee, K. Y. Altered adipose tissue and adipocyte function in the pathogenesis of metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 3990–4000 (2019).

Sun, W. et al. snRNA-seq reveals a subpopulation of adipocytes that regulates thermogenesis. Nature 587, 98–102 (2020).

Maniyadath, B., Zhang, Q., Gupta, R. K. & Mandrup, S. Adipose tissue at single-cell resolution. Cell. Metab. 35, 386–413 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. AMPK/mTOR signaling in autophagy regulation during Cisplatin-Induced acute kidney injury. Front. Physiol. 11, 619730 (2020).

Chun, Y. & Kim, J. AMPK-mTOR signaling and cellular adaptations in hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 9765 (2021).

Varol, C., Mildner, A. & Jung, S. Macrophages: development and tissue specialization. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 33, 643–675 (2015).

Tamaki, S. et al. Production of inflammatory mediators by monocytes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Intern. Med. 48, 1255–1262 (2009).