Abstract

Wheeled mobile robots are efficient on flat surfaces but face limitations in overcoming obstacles like steps due to their fixed wheel radius. This paper presents a novel modular reconfigurable wheel with a dual-degree-of-freedom active reconfigurable mechanism, designed to adapt dynamically to varying step sizes. The wheel’s structure includes three curved segments, whose synchronized motion is driven by five-bar linkages and two planetary gear systems. By analyzing the kinematic constraints and both forward and inverse kinematics of the reconfigurable wheel, we established the range of dimensions it can surmount over steps, specifically focusing on height and depth, as well as the relationship with the output angles \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) of the two motors driving the reconfiguration. Simulations using ADAMS software demonstrates the wheel’s capability to maintain smooth, continuous center-of-mass movement over steps and stairs. Moreover, physical prototype testing further confirms the feasibility and advantages of the proposed wheel structure. This adaptive design significantly enhances the performance of wheeled robots in navigating complex environments, offering promising potential for applications in challenging terrain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the rapid development of mobile robot technology, its applications are expanding, especially in military scenarios such as urban counter-terrorism, rescue operations, nuclear radiation detection, and fire search and rescue1,2. In these dangerous environments, deploying mobile robots instead of personnel significantly reduces the risk of unnecessary casualties. However, the military field presents not only highly complex and hazardous operating conditions, but also demands that mobile robots respond swiftly and adapt to dynamic environmental changes. These factors pose significant technical challenges for mobile robots, particularly in terms of environmental adaptability, mobility, and task efficiency3,4,5.

Currently, mobile robots can be categorized into three main types: tracked, legged6, and wheeled, each with distinct advantages7. On structured, flat surfaces, wheeled robots are favored for their efficiency, low energy consumption, and ease of control8,9. However, obstacles like steps and stairs often become major challenges for wheeled robots, especially when their wheel radius is limited, hindering efficient traversal10. Tracked robots, while capable of overcoming such obstacles with rocker arm mechanisms, suffer from high energy consumption and lower motion efficiency11,12. Legged robots, though adept at crossing steps due to discrete support points, face high control complexity, making it difficult to match the locomotion efficiency of wheeled robots13.

To address these challenges and enhance the adaptability of mobile robots in complex environments, particularly when encountering steps and stair-like obstacles, while maintaining efficient movement on flat surfaces, this paper introduces a mobile robot equipped with a dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel. This design allows the robot to retain the efficient motion characteristics of traditional wheeled robots on flat terrain. When faced with obstacles such as steps, the Reconfigurable wheel can actively adjust its radius and rim deflection angle, enabling a wheel-leg hybrid motion, which ensures smooth and efficient traversal of various step-like obstacles.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

A novel dual-degree-of-freedom active modular reconfigurable wheel is developed, featuring synchronized movement of a three-segment rim through a parallel five-bar mechanism combined with a planetary gear system.The adjustable radius (r) and rim deflection angle (\(\theta\)) allow the wheel to actively deform and adapt to different obstacle sizes, offering optimal performance on both flat surfaces and varied step-like obstacles. This dual-functional design enhances both energy efficiency and speed on flat terrains, while ensuring smooth and adaptive traversal over complex obstacles. Additionally, the modular structure enables easy integration into existing wheeled robot platforms, offering scalability, reduced maintenance complexity, and enhanced adaptability across a range of robotic systems.

-

The kinematic model and motion constraints of the reconfigurable wheel are thoroughly analyzed, including both its forward and inverse kinematic properties. This analysis defines the reconfiguration constraints and derives the range of variation for the input variables, enabling the determination of step sizes the wheel can traverse. Furthermore, the relationship between obstacle dimensions and corresponding input variables is established, ensuring precise adaptation to varying step sizes.

-

Simulation and physical prototype experiments were conducted to validate the reconfigurable wheel’s performance. A detailed simulation model in ADAMS demonstrated the wheel’s ability to dynamically adapt to various step sizes, successfully performing tasks such as ascending and descending stairs and crossing double-sided steps without altering the vehicle’s direction. The physical prototype tests further validated the wheel’s structural integrity and superior real-world performance, confirming its robustness and effectiveness in overcoming step-like obstacles. Results of simulation and experimental highlight the wheel’s practical application potential in challenging environments.

The remaining structure of this paper is organized as follows: In section “Related work”, we review existing research and prominent solutions related to reconfigurable wheel designs. Section “Modular reconfigurable wheel design with adaptive dual-degree-of-freedom mechanism” introduces the concept of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel and its theoretical implementation. In the mechanical structure design of the active reconfigurable wheel is discussed in detail, and a mobile robot with reconfigurable capability is designed based on this concept. Section “Kinematics of reconfigurable wheels” analyzes the forward and inverse kinematics models of the reconfigurable wheel, along with its motion constraints. Section “Simulation and experimental studies” validates the surmounting ability and structural integrity of the reconfigurable wheel through ADAMS simulation and physical prototype experiments. Finally, in section “Conclusions”, we summarize the research findings and outline future work directions.

Related work

Stairs and steps are common obstacles in daily life, and developing mobile robots capable of overcoming these obstacles holds both significant academic value and practical potential. However, since steps and staircases make up only a small portion of flat ground, the ideal robot must not only efficiently cross these obstacles but also maintain high performance on smooth, structured surfaces. To address this dual requirement, researchers have proposed various strategies aimed at combining the efficient locomotion of wheeled robots on flat surfaces with the ability to navigate steps, leading to important breakthroughs. Early studies introduced mobile robots with shaped wheel structures, where circular rims were divided into multiple sections to enhance adaptability to uneven terrain. Notable examples include ASGUARD14,15,16, amphibious miniature robots17, the RHex-style hexapod18,19,20,21, the Levo mobile robot22,23,24,25, and FleTbot26. While these robots gradually improved trajectory smoothness when crossing steps and reduced reliance on external factors such as friction, they often experienced significant bumps during movement on flat surfaces, affecting efficiency and stability. To address these issues, reconfigurable wheels were developed. Unlike shaped wheels, reconfigurable wheels can smoothly and efficiently move on flat surfaces in their circular form, while transitioning into a “wheel-leg” configuration when encountering obstacles, thus enhancing their ability to cross complex terrain.

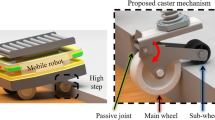

Current research on reconfigurable wheels can be broadly categorized into two types: passive reconfigurable wheels and active reconfigurable wheels. Passive reconfigurable wheels rely on friction between the wheels and the ground or steps, combined with a trigger mechanism, to alter their shape and achieve obstacle-crossing capabilities. Notable examples of such designs include the Land Devil Ray27, WheeLeR28,29, \(\alpha\)-WaLTR30, Wheel Transformer31,32, Shape-Morphing Robot33, Cylindabot34, the deformed wheel-based robot by Manhong Li35,36, and the reconfigurable wheel-legged mobile robot by Shuo Zhang et al.37. While these designs perform well on flat surfaces and can cross steps using a wheel-legged configuration, they depend heavily on external friction to trigger the reconfiguration process. This reliance on external factors results in poor stability and inconsistent success rates during reconfiguration, introducing uncertainty into the system and limiting their overall reliability in dynamic environments.

To address the uncertainty of passive reconfiguration wheels during the reconfiguration process, active reconfiguration wheels became a new research focus. These wheels achieved controllable reconfiguration through motorized actuation, significantly reducing dependence on the external environment. A notable example was the Quattroped wheel-legged robot38, which improved step-crossing ability by morphing a circular wheel into a semi-circular shape via a gear mechanism. However, the need for the robot to briefly stop and adjust its wheel morphology while traversing consecutive stairs reduced task efficiency. To address this, the team developed the TurboQuad mobile robot, which eliminated the need to pause by optimizing its design. Nevertheless, it still relied on friction between the wheels and the step edge to overcome obstacles39,40. Other designs, such as SWhegPro41 and R-Taichi42, shared similar step-overcoming principles to TurboQuad, differing mainly in the structures that drove wheel shape changes. However, they suffered from the same limitations regarding efficiency and dependence on friction. Additionally, some wheel-leg structures, like OmniWheg43 and Trimode44, relied on the wheel rim hooking onto the step tread to climb, resulting in sharp changes in the robot’s center-of-mass trajectory, making the motion less smooth. A solution proposed in the literature45 addressed these issues by using the wheel rim’s surface to contact the step, relying on motor torque and step support to achieve smoother step-crossing. Although these robots based on active reconfigurable wheels demonstrated both efficient movement on flat surfaces and stair-climbing abilities, their reconfigurable mechanisms typically had only one degree of freedom, limiting their adaptability to different step sizes. In addition, since the reconfigurable process in many designs was not adaptive, it often resulted in less smooth trajectories when climbing stairs. To address this, Hanyang University in South Korea developed the STEP robot46, which optimized the design of reconfigurable wheels by introducing two degrees of freedom. This allowed the wheels to adaptively adjust according to the step size, with a similar step-overcoming principle to that described in45. The design achieved greater environmental adaptability and smoother motion. However, the STEP robot utilized two motors embedded in the body to drive the reconfigurable process, along with a ball screw transmission system. This resulted in a bulkier overall structure, which limited its application in narrow spaces and lacked modularity.

Inspired by these previous works and summarizing the advantages and disadvantages of the previous works as shown in Table 1, this study proposes a novel dual-degree-of-freedom adaptive modular reconfiguration wheel. The new design combines flexibility with efficient movement, addressing the limitations of existing reconfigurable wheels regarding degrees of freedom, compactness, and modularity, while enhancing robot performance in navigating complex terrains.

Modular reconfigurable wheel design with adaptive dual-degree-of-freedom mechanism

Concept of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel

A dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel offers the potential to surmount a wider range of step sizes, but defining and implementing these dual degrees of freedom is critical to its design and one of the key focuses of this paper. The aim is to create a wheel that combines the efficient locomotion capabilities of traditional wheels with the stair-climbing advantages of wheel-legged robots. To achieve this, the circular wheel serves as the base frame for the reconfigurable mechanism, while the wheel-leg functionality is achieved by splitting the wheel rim, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The rim of the circular wheel is divided equally into three parts, forming the segmented rim of the novel reconfigurable wheel. For this new wheel, the primary factors influencing step-climbing performance are the distance of each rim section from the center of mass of the wheel (i.e., the radius, r) and the rotational angle of each rim section around its connecting rod (i.e., the deflection angle, \(\theta\)). In this paper, these two parameters-radius r and deflection angle \(\theta\)-are defined as the dual degrees of freedom for the reconfigurable wheel. The focus is on analyzing their relationship with the wheel’s ability to surmount steps of varying sizes.

As shown in Fig. 1, the simplified structure of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel exhibits four primary configurations, illustrated in Fig. 1a through d. Each configuration can be flexibly switched between, and the specific switching mechanisms will be discussed later in detail. The transformations in wheel morphology in Fig. 1a and b are determined solely by the adjustment of the wheel radius, while the configurations in Fig. 1c and 1d are influenced not only by the radius r but also by the rim deflection angle \(\theta\). The key distinction between these two configurations lies in the direction of rim rotation: the rim in Fig. 1c rotates counterclockwise, while the rim in Fig. 1d rotates clockwise. These four reconfigurable wheel configurations correspond to the mobility strategies of the robot in various environments. The configuration in Fig. 1a is ideal for flat, smooth surfaces, preserving the efficiency of traditional wheeled robots. The morphology in Fig. 1b is suitable for crossing lower obstacles, temporarily enlarging the wheel radius to improve passability and smoothness. Figure 1c and d represent the configurations for descending and ascending stairs, respectively. By adjusting both the wheel radius and the rim deflection angle, the robot can smoothly ascend or descend stairs without needing to change direction, enhancing operational efficiency. The values of the two degrees of freedom parameters \(\left( r,\theta \right)\) are determined by the size of the encountered obstacles. Adjusting the wheel’s reconfiguration based on varying obstacles not only improves the robot’s stability when overcoming obstacles but also ensures smooth and accurate trajectory control.

The climbing attitude of the reconfigurable wheel plays a critical role in determining both the success rate of overcoming steps and the smoothness of the robot’s trajectory. Previous passive and active reconfigurable wheels typically rely on two approaches when crossing steps: either by hooking the step tread with the wheel rim to pull the wheel over, or by using the friction between the wheel rim and the step nose to climb. The former method often results in abrupt changes in the trajectory and acceleration, leading to an uneven center-of-mass trajectory. The latter approach depends on a high friction coefficient between the outer surface of the wheel rim and the step nose, which limits performance if friction is insufficient. The reconfigurable wheel proposed in this paper adopts a more efficient climbing attitude, shown in Fig. 2, which reduces the required friction coefficient while ensuring a smoother trajectory22. In Fig. 2D and H denote the depth and height of the step, respectively, while \(\epsilon\) and \({r_0}\) represent the center angle and radius of the wheel rim. To balance the ability to surmount the step with movement smoothness, the rim is divided into three equal parts, resulting in \(\epsilon =2\pi /3\). Using the climbing approach illustrated in Fig. 2, this paper establishes the kinematic relationship between the dual degrees of freedom of the reconfigurable wheel and the step depth and height. Considering the design standards for common staircases, this paper selects \(r_0=135mm\). Using Eq. (1), the required value of reconfiguration for the wheel to surmount steps of different sizes can be calculated. This ensures that the reconfigurable wheel can be effectively applied across a wide range of scenarios.

Theoretical design of a dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel

Based on the concept of a dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel and the principles of mechanical design, this paper details the structure of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel. During the design process, two major challenges must be addressed: first, how to achieve dual-degree-of-freedom motion within the confined space of the wheel, specifically controlling both the scaling of the rim’s distance r relative to the wheel’s center, and the change in the rim’s turning angle \(\theta\); second, since the wheel’s rim is divided into three segments to enable smooth step-climbing, ensuring the synchronized movement of these segments poses another critical challenge. To tackle these issues, the composite structure shown in Fig. 3 was designed, which integrates the planetary gear system Fig. 3a) with a parallel five-bar mechanism (Fig. 3b). The final configuration of the reconfigurable wheel (Fig. 3c) is realized through the effective combination of these systems. This composite structure addresses both the dual-degree-of-freedom motion requirements and the need for synchronized motion between the rim segments. The five-bar mechanism (Fig. 3b) is the core component responsible for driving the motion of each individual rim segment. This mechanism consists of two prismatic pairs and three revolute pairs, forming a PRRRP-type mechanism (two prismatic joints and three revolute joints). The degree of freedom (DOF) of this mechanism is determined by the formula for planar mechanisms, as derived from Eq. (2):

where F represents the number of degrees of freedom, n denotes the number of mechanism components, \(P_l\) indicates the number of lower pairs, and \(P_h\) indicates the number of higher pairs.

The planetary gear train shown in Fig. 3a consists of a sun gear and three planetary gears, primarily used to power the PRRRP five-bar mechanism illustrated in Fig. 3b. The sun gear is directly connected to the motor responsible for morphology change via a shaft and a flange, while the three planetary gears are fixed to the motor’s bracket with shafts of different lengths and are staggered in the transverse direction. Notably, the tooth width of the sun gear needs to be appropriately widened to ensure proper meshing with the staggered planetary gears. The PRRRP parallel five-bar mechanism shown in Fig. 3b has left and right active linkages that are connected to the motor’s bracket via sliders. Each rim can be considered a linkage, connected through two revolute pairs. To form a reconfigurable wheel, three sets of five-bar mechanisms with identical structures are required, corresponding to the three rims. Figure 3c further illustrates the integration between the two sets of planetary gear trains and the three sets of PRRRP five-bar mechanisms, as well as the spatial distribution of the entire composite mechanism. This design effectively combines transmission and deformation functions, providing stable and efficient power support for the morphology changes of the reconfigurable wheel.

The planetary gears engage with racks attached to the connecting rods, converting the circular motion of the gears into the linear reciprocating motion needed in the five-bar mechanism. The two guide rails in this system ensure a smooth and controlled path for the reciprocating motion. The linkages, as shown in Fig. 3c, are color-coded, with rods of the same color driven by the same power source. The dashed circle represents the planetary gear system, symmetrically arranged but hidden from view. This system includes two sets of powertrains, each responsible for controlling one degree of freedom. These two sets of planetary gear systems generate synchronized linear forces, which are transmitted to the three five-bar mechanisms. This synchronization guarantees coordinated movement of each rim, allowing the wheel to deform smoothly and operate effectively. This precise motion enables the wheel to handle varied terrains, including the efficient crossing of obstacles like steps.

Design of a mobile robot utilizing a reconfigurable wheel

Design of a modular dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel

Based on the design principles of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel, the width and length of each link in the five-bar mechanism are carefully optimized, and the planetary gears are precisely arranged to be staggered along the wheel’s axial direction. This configuration not only prevents interference between the three links on the same side of the motor bracket during reciprocating motion but also expands the available movement space for the links. As a result, the reconfigurable wheel achieves greater adaptability to a wider range of step sizes. Furthermore, the dual-degree-of-freedom motion of the PRRRP five-bar mechanism requires two actuators to provide power, and the placement of these actuators significantly influences the overall design of the reconfigurable wheel. While installing the actuators inside the robot body simplifies the wheel’s structural design, transferring the force required for wheel reconfiguration to the wheel itself demands an additional transmission mechanism. This setup often leads to coupling issues between the reconfiguration drive and the wheel rotation drive, ultimately increasing both system complexity and control difficulty. Conversely, embedding the actuators directly within the reconfigurable wheel mitigates the transmission coupling issue but increases the wheel’s weight and structural complexity. Moreover, this arrangement necessitates the use of a slip ring to supply power and control signals to the actuators. In practice, the optimal actuator arrangement must be selected based on the specific application scenario and design goals. Given that the focus of this paper is on the modularity of the reconfigurable wheel, we ultimately chose to house the actuators within the wheel itself, prioritizing system independence and integration.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the 3D model of the reconfigurable wheel showcases its structural arrangement. Two brushless direct current motors (BLDC) are symmetrically positioned along the axial direction of the wheel. The racks, which are mounted on the connecting rods, engage with gears, while guide rods interface with sliders attached to the motor frame on either side of the connecting rods. The racks attached to connecting rods of varying widths engage with axially staggered planetary gears, while the sun gear, which meshes with the planetary gears, is fixed to the motor shaft to power the connecting rod system.

Figure 5 illustrates the conceptual design schematic of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel corresponding to the 3D model. The top half of the figure presents the conceptual design schematic, while the bottom half displays the associated 3D model. Together, they demonstrate the motion and interaction of each linkage as the wheel’s configuration changes. As shown in Fig. 5b, when the wheel’s reconfiguration involves only a change in radius, the green and red connecting rods extend or retract equally relative to the slider. Correspondingly, the green and red planetary gears rotate by the same angle but in opposite directions, providing synchronized power for the reconfiguration process. However, when both the radius r and the rim deflection angle \(\theta\) are adjusted simultaneously (as shown in Fig. 5a and c), the green and red connecting rods move by different distances relative to the slider, with their respective planetary gears rotating at different angles. The 2-DOF system is designed to allow the reconfigurable wheel to flexibly adapt to varying environments and smoothly traverse different types of obstacles.

Design of a two-wheeled mobile robot utilizing reconfigurable wheels

The mobile robot, based on a dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel design, is equipped with two reconfigurable wheel modules, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Each module comprises several key components: a drive motor responsible for wheel rotation, a gear set with a 2:1 reduction ratio, a slip ring for seamless power transmission, and the reconfigurable wheel, whose detailed structure is depicted in Fig. 4. The core systems of the robot-including the power supply, controller, and motor driver for wheel rotation-are centrally housed within a yellow casing. Additionally, a LiDAR system is mounted on the housing for environmental sensing, enabling the robot to gather real-time data for optimal navigation and task execution. This design enhances the robot’s adaptability to complex terrain while ensuring high modularity and ease of maintenance.

Kinematics of reconfigurable wheels

Figure 7 presents a schematic diagram illustrating the dual-degree-of-freedom motion of the reconfigurable wheel, along with the composite interaction between the linkage and gear train that drives each wheel rim. From the Fig. 7, it can be observed that the red sun gear functions as the active gear, driving the red planetary gears. This red planetary gear meshes with a rack that actuates the linkage \({l_1}\) in a reciprocating up-and-down motion. As \({l_1}\) moves, it in turn drives the motion of \({l_2}\), which is connected via a revolute pair, thus transferring the motor’s driving force to the wheel rim. The green drive chain, opposite the red drive chain, is powered by the rotation of the green sun gear, which drives the rotation of the corresponding planetary gears. This planetary gear meshes with a rack, pushing the linkage \({l_4}\) to reciprocate. This motion transmits the force from the second drive system to the rim of the wheel. The coordinated rotation of the two drive systems ultimately results in the adjustment of both the wheel’s radius r and the rim’s deflection angle \(\theta\). In Fig. 7, the wheel rim is connected to the line segments \({l_2}\) and \({l_4}\), but the connection is replaced by the connecting rod \({l_3}\), as shown by the black dashed line.

In Fig. 7, the radius r of the rim corresponding to one of the dual degrees of freedom of the reconfigurable wheel is represented by the line segment \({O_2O_1}\), while the angle \(\theta\) of the rim’s rotation for the other degree of freedom is indicated by the angle between \({O_2O_1}\) and \({O_2O}\). As illustrated, the linear sliding of the \({P_3P_4}\) linkage along the radius directly relates to the radius r of the reconfigurable wheel, while the rim’s rotational angle relative to \({P_3}\), denoted as \(\gamma\), corresponds to the rim’s angle of rotation \(\theta\). The relationship between the staircase dimensions and the dual degrees of freedom of the reconfigurable wheel (radius r and rotation angle \(\theta\)) while overcoming a staircase obstacle is defined by Eq. (1). This equation enables the calculation of the required degrees of freedom for the reconfigurable wheel to effectively navigate a staircase of a specific size. Although the required degrees of freedom for surmounting a staircase can be derived from Eq. (1), the relationship between the dual degrees of freedom of the reconfigurable wheel and the drive motors is not yet fully understood. Therefore, it is crucial to analyze the kinematics of the reconfigurable wheel. Specifically, investigating how the rotation angles \({q_1}\) and \({q_2}\) of the two brushless direct current motors (BLDC) relate to the radius r of the reconfigurable wheel and the rim’s rotation angle \(\theta\) will provide insights into controlling the kinematic behavior of the reconfigurable wheel more effectively. This analysis will enable the precise coordination of the motors to achieve desired reconfiguration states, ultimately enhancing the robot’s capability to navigate complex environments.

Forward kinematics of reconfigurable wheels

The forward kinematics of the reconfigurable wheel is determined by calculating the angles \({q_1}\) and \({q_2}\) of the two sun gears to derive the wheel radius (r) and rim inclination (\(\theta\)), ultimately determining the size of the step that can be overcome at the corresponding motor angles. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the lengths of the connecting rods \({P_0P_1}\) and \({P_3P_4}\) vary within the stroke range of the racks, with their variations directly influenced by the rotation angles \({q_1}\) and \({q_2}\). In the initial state, the lengths of \({P_0P_1}\) and \({P_3P_4}\) are denoted as \({l_1}\) and \({l_4}\), respectively. Additionally, the other fixed linkages are defined as follows: \({l_2}\) for \({P_1P_2}\), \({l_3}\) for \({P_2P_3}\), and \({l_5}\) for \({O_2P_3}\). The planetary gears have a radius \({r_2}\), while the sun gears have a radius \({r_1}\). The angle of rotation for \({P_1P_2}\) is represented by \(\phi\), and \({P_2P_3}\) has a turning angle of \(\psi\). The parameters corresponding to the above mechanisms are shown in Table 2. To establish the kinematic model, a coordinate system \({O_1XY}\) is defined, with \({O_1}\) as the coordinate origin. Within this coordinate framework, the coordinates of each key point \({P_i}\) (where \({i=0,1,2,3,4}\)) can be derived from the geometrical relationships of the connecting rods. Using these coordinates and the associated geometric constraints, the radius r of the reconfigurable wheel and the rotation angle \(\theta\) can be calculated, thereby completing the forward kinematic analysis of the reconfigurable wheel. This comprehensive understanding of the kinematic relationships will ultimately facilitate more precise control of the wheel’s reconfiguration and motion in various environments.

Where,

Where i denotes the reduction ratio between the sun wheel and the planetary wheel, \(dl_1\) denotes the amount of \(P_0P_1\) variation, and \(dl_4\) denotes the amount of \(P_3P_4\) variation.

From the coordinates of point \(P_2\) in Eq.(3) we can obtain the following relationship:

Solving for \(\phi\) and \(\gamma\) in Eq. (5) yields:

Where,

The radius r of the distance between the rim and the center of mass of a reconfigurable wheel is solved as follows:

The flange angle \(\theta\) of a reconfigurable wheel is solved as follows:

From Eqs. (8) and (9), the radius r of the reconfigurable wheel and the angle of the rim \(\theta\) are functions with respect to \(P_{3y}\) and \(\gamma\), and all other parameters are known, so it is perfectly possible to represent the dual degrees of freedom of the reconfigurable wheel \(\left( r,\theta \right)\) using \(\left( P_{3y},\gamma \right).\)

Range of climbable stair sizes

As shown in Fig. 5, the rim of the reconfigurable wheel can be driven by two connecting rods to achieve either counterclockwise or clockwise rotation. Theoretically, when the stroke of the green connecting rod exceeds that of the red connecting rod, the rim will rotate counterclockwise; conversely, if the green connecting rod’s stroke is less than that of the red, the rim will rotate clockwise.

In order to achieve the two-degree-of-freedom shape transformation of the reconfigurable wheel, this paper adopts a parallel five-bar mechanism based on the PRRRP configuration. As shown in Fig. 5b, during the counterclockwise rotation of the rim, the initial positions of \(R_1,R_2,R_3\) form a Right Angle triangle \(\Delta R_1R_2R_3\). However, with the movement of the active link \(l_4\), the phenomenon shown in Fig. 8(b) may occur, where links \(l_2\) and \(l_3\) become collinear, satisfying the condition \(l_2+l_3=l_5\). In this case, \(R_2\) becomes a singular point. Motion near the singular point may lead to unexpected behaviors, such as the inward movement of point \(R_2\), abnormal force transmission, and errors in inverse kinematics solutions. Therefore, a detailed analysis of the singular point is necessary.

Figure 9 shows the variations of the five-bar mechanism during the clockwise rotation of the rim. The difference between Fig. 9a and b lies in the triangles \(\Delta R_1R_2R_3\) formed by the red dashed and solid lines, primarily due to the conditions \(dl_1-dl_4<l_2\) or \(dl_1-dl_4>l_2\). Similarly, potential singular points need to be considered. From the perspective of geometric configuration, the occurrence of singular points would prevent the formation of the triangle \(\Delta R_1R_2R_3\). To minimize the occurrence of singular points, constraints can be imposed on the motion of the two active links, ensuring that they always satisfy the trilateral relationship of the triangle during their motion.

Since the lengths of \(l_2\) and \(l_3\) are constant, while the length of \(l_5\) is variable and the distance \(l_6\) between the two active links is also constant, the key factors determining whether the triangle satisfies the trilateral relationship of the triangle are the lengths of \(dl_1\) and \(dl_4\). As shown in the figures, \(l_5\) is the longest side of the triangle, and \(l_2\) is the shortest side. Therefore, the triangles \(\Delta R_1R_2R_3\) shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9 need to satisfy the following triangle inequality conditions:

For \(l_5\) in the \(\Delta R_1R_2R_3\) shown in Fig. 8 is:

For \(l_5\) in the \(\Delta R_1R_2R_3\) shown in Fig. 9 is:

In addition, as shown in Fig. 10, the reconfigurable wheel may cause the rim to interfere with the bracket of the motor when it is reconfigurable, so in order to avoid the interference, it is necessary to ensure that the \(\left| {{x_{{G_i}}}} \right| > \left| {{x_{{L_i}}}} \right| ,i = 1,2\) of the rim edge point \(G_i\), regardless of whether the rim is rotated counterclockwise or clockwise, i.e., the following constraint should be satisfied:

The range of the wheel radius (r) and rim inclination angle (\(\theta\)) is shown in Fig. 11b, given that the input variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) of the reconfigurable mechanism satisfy the constraints defined by Eqs. (10), (13) and (14). Figure 11 also highlights the relationship between these dual degrees of freedom and the dimensions of the steps that can be surmounted by the reconfigurable wheel. This graphical representation helps to visualize how the design parameters interact and informs the capabilities of the wheel in navigating obstacles of varying sizes.

The radius r and declination angle \(\theta\) of the reconfigurable wheel are jointly controlled by the two motor input variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\). As these input variables are adjusted, the geometry of the reconfigurable wheel-specifically its radius and declination-changes accordingly to adapt to steps of different heights and depths. Figure 11 illustrates the relationship between the dimensions of the steps that the robot can overcome and the dual degrees of freedom that govern the reconfiguration wheel’s morphology. Figure 11a and b show the range of depths and heights of the steps that the reconfigurable wheel can traverse, along with the corresponding variation ranges for the wheel’s radius and rim deflection angle. These results assume that the input variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) satisfy the inequality constraints described earlier. Figure 11c and d illustrate the relationship between the radius and inclination of the wheel and the depth and height of the surmountable step, respectively. From the analysis presented in Fig. 11, it becomes clear how the dual degrees of freedom in the motion of the reconfigurable wheel can be matched to the size of environmental obstacles. This demonstrates the versatility of the reconfigurable wheel, showing that it is capable of overcoming most typical steps encountered in daily human environments.

Inverse kinematics of reconfigurable wheels

The inverse kinematics of the reconfigurable wheel focuses on determining the required wheel radius r and declination angle \(\theta\) based on the height H and depth D of a stair step, with the ultimate goal of calculating the angles \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) that need to be rotated by the red and green sun gears, respectively. The reconfigurable wheel’s main advantage is its ability to adaptively adjust its radius and rim angle to different step sizes, enhancing stability and smooth when overcoming obstacles. Solving the inverse kinematics allows the wheel to automatically configure for optimal performance, reducing vibrations and minimizing sudden shifts in the robot’s center of mass. This adaptive adjustment improves the robot’s ability to traverse complex terrains smoothly, boosting smoothness and flexibility, especially on uneven surfaces.

Compared to existing state-of-the-art morphing wheels, our design offers greater flexibility in adaptive adjustments. Conventional reconfigurable wheels often rely on a fixed rim pattern, which can cause significant shifts in the wheel’s center of mass when encountering certain step sizes, thus compromising smoothness. In contrast, our design allows for more precise control by adjusting both the wheel radius r and rim angle \(\theta\), enabling smoother and more stable navigation across obstacles of varying sizes. Therefore, studying the inverse kinematics of reconfigurable wheels not only helps establish the relationship between the control inputs \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) and the wheel morphology parameters r and \(\theta\), but also provides a theoretical foundation for enhancing the stability and adaptability of the reconfigurable wheels.

First, it is necessary to determine the radius r of the reconfigurable wheel and the rim angle \(\theta\) required to overcome a step of any given size, as defined by Eq. (1):

Based on the radius r of the desired reconfigurable wheel and the rim angle \(\theta\), the angle \(\left( q_1,q_2\right)\) is solved for the red and green sun gears, and the following functional relationship is obtained from Eqs. (8) and (9):

Equation (16) contains two unknown parameters \(\left( \gamma ,q_{2}\right)\) and two equations, so it is possible to solve for the two unknown parameters based on the known radius r of the reconfigurable wheel and the rim angle \(\theta\).

To derive the equations for the angles of rotation of the red and green sun gears \(\left( q_1,q_2\right)\) that correspond to the desired values of \(\left( \gamma ,q_{2}\right)\) and \(\gamma\) (the angle of rotation), we need to express \(q_1\) in terms of these desired parameters based on Eqs. (6) and (7).

Jacobian analysis for reconfigurable wheels

According to the formula for determining the coordinates of \(P_{3y}\) in Eq. (3), we have \(f_1\left( P_{3y},q_2\right) =0\). Similarly, based on the formula for solving \(\gamma\) in Eq. (6), we have \(f_2\left( \gamma ,q_1,q_2\right) =0\). By differentiating these two functions with respect to time t, respectively, we obtain:

Thus the Jacobi matrix can be expressed as

Where,

Simulation and experimental studies

To evaluate the passing ability of dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheels over various step-like obstacles, we designed experiments using a mobile robot equipped with the reconfigurable wheel. In our simulation experiments, we first created a 3D model of the mobile robot in SolidWorks, which we then imported into ADAMS for dynamic simulation analysis. Using ADAMS, we simulated the motion of the reconfigurable wheel as it traversed stairs of varying sizes and orientations, focusing on its motion trajectory and posture during these crossings. The simulation results effectively assessed the adaptability of the reconfigurable wheel to different geometric configurations of steps, particularly regarding the smoothness of its trajectory while overcoming obstacles. Additionally, we constructed a physical prototype to validate the structural design of the reconfigurable wheel, further confirming its effectiveness in real-world applications.

Validation of passage through steps of various sizes

Figure 12 illustrates the simulation experiment of the reconfigurable wheel crossing a step with dimensions 283mm in depth and 100mm in height. Figure 12a–f depict the various attitudes of the reconfigurable wheel during this process. The wheel begins and ends in a circular shape, indicating that it maintains the efficient, energy-saving characteristics of wheeled motion on flat ground. Upon encountering a step, as shown in Fig. 12b, the wheel deforms in preparation for the ascent. Figure 12c and d illustrate the actual crossing, while Fig. 12e and f depict the recovery phase.

Notably, in the reconfigurable process shown in Fig. 12b and c, the green linkage near the step extends more than the yellow linkage on the opposite side. This design enables a smooth elevation of the wheel’s center of mass while allowing the rim to rest gently on the step. Unlike passive reconfigurable wheels, this mechanism minimizes abrupt changes in the center-of-mass trajectory during the transition. Additionally, the rim’s rotation during reconfiguration ensures that the lower side on the step remains at a lower height, thereby preventing significant shifts in the center of mass. This advantage of the dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel enhances its smoothness compared to passive designs. The specific reconfiguration parameters for this step size can be calculated using the formulas from Section 5.2, with detailed values provided in Table 3.

Figure 13a and b illustrate the simulation experiments of the reconfigurable wheel surmounting steps with dimensions of 283 mm \(\times\) 130 mm and 283 mm \(\times\) 150 mm, respectively. While the overall attitude change during the surmounting process is consistent with that shown in Fig. 12, the key difference lies in the varying reconfiguration amounts of the wheels tailored to the different step sizes. Closer examination reveals that as the step height increases, the linkage extension on the side adjacent to the step correspondingly increases to accommodate the higher obstacles.

Figure 14 presents experiments where the reconfigurable wheel crosses a series of steps with varying sizes: 283 mm \(\times\) 100 mm, 283 mm \(\times\) 120 mm, 283 mm \(\times\) 140 mm, and 283 mm \(\times\) 160 mm, respectively. For each step size, the reconfigurable wheel employs distinct reconfiguration amounts, with the specific methods for these adjustments detailed in Sections 5.1 and 5.2 of the current manuscript. The corresponding input parameters for each step size are provided in Table 3. Meanwhile, Fig. 15a illustrates the variations of input variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) as the wheel climbs steps of different sizes, as well as the changes in the wheel’s configuration parameters \(\left( \phi ,\gamma ,r\right)\) that determine its shape. Additionally, the relationships between these input variables and the wheel’s radius r and angles \(\left( \phi ,\gamma \right)\) are presented. The kinematic graphs provide an in-depth understanding of how the wheel’s shape adapts when climbing steps of varying sizes. Figure 15b shows the variation trends of the torque required to drive the wheel’s rotation \(\left( \tau -\phi \right)\) and the torque for the wheel’s shape adaptation \(\left( \tau -q_1,\tau -q_2\right)\) when overcoming steps of different sizes. The graphs clearly illustrate the torque variation trends of the wheel motors during the climbing of steps with various sizes. These experiments demonstrate the reconfigurable wheel’s ability to flexibly and adaptively adjust, ensuring smooth traversal across steps of varying dimensions.

Figure 16 depicts the center of mass trajectories of the reconfigurable wheel as it navigates various step sizes. The trajectory closely aligns with the incline of the staircase, showing no significant spikes or fluctuations in the center of mass throughout the crossing process, which reflects a high level of smoothness. Additionally, the reconfigurable wheel demonstrates impressive adaptability to different step sizes, maintaining a smooth trajectory while successfully overcoming obstacles of varying heights. These findings underscore the effectiveness and superiority of the reconfigurable wheel’s structural design, affirming its reliability in diverse and complex environments.

Figures 17 and 18 present the experimental procedure of reconfigurable wheels traversing steps of varying depths, along with their corresponding center-of-mass trajectories. These experiments compare the wheel’s trajectories and reconfigurations when crossing steps of the same height but different depths. The results indicate that the reconfigurable wheel can smoothly navigate deeper steps by increasing its reconfiguration. Furthermore, Fig. 18 shows that while the curvature of the center of mass trajectory increases with step depth, the overall trajectory remains relatively smooth. This highlights the reconfigurable wheel’s capacity to adaptively adjust its reconfiguration, ensuring a smooth trajectory across various step sizes, and underscores its superior design and exceptional adaptability.

In summary, this section analyzes simulation experiments involving reconfigurable wheels navigating three types of staircases: 1) different staircases but each staircase has the same step size, while different staircases have the same depth and different heights; 2)the same staircase but each step has the same depth and different heights; and 3) different staircases but each staircase has the same step size, while different staircases have the have the same height and different depths. The experimental results demonstrate the adaptability of the designed reconfigurable wheel to different step heights. Additionally, the smoothness of the center-of-mass trajectory is significantly enhanced by employing different reconfiguration strategies tailored to each step size. Through the inverse kinematics analysis in section “Verification of passage over stairs and bi-directional obstacles”, the input variables needed to navigate various step sizes can be determined, with specific values presented in Table 3. This analysis further validates the effectiveness of the reconfigurable wheel in complex terrain and underscores the soundness of its design.

Verification of passage over stairs and bi-directional obstacles

In this section, we conduct experiments to verify that the designed reconfigurable wheels can ascend and descend stairs and climb bilateral stairs by adjusting the relationship between the input variables \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) without changing the direction of travel. To facilitate this, an experimental environment was designed, as illustrated in Fig. 19. These experiments further confirm the flexibility and stability of the reconfigurable wheel in complex terrains, showcasing its adaptive reconfiguration capabilities to accommodate varying environments.

As illustrated in Fig. 19, the processes of descending and ascending with the reconfigurable wheel are divided into several phases: the descending preparation phase, the descent phase, the recovery and ascending preparation phase, the ascent phase, and the final recovery phase, corresponding to Fig. 19a–f. In the descent phase (Fig. 19b), the yellow linkage, positioned away from the step, extends more than the green linkage, indicating that \(q_1>q_2\). This operation effectively lowers the center of mass while the wheel rolls on the platform. As the wheel rotates, the next flap of the rim contacts the step at the lowest point, preventing a sudden drop in the center of mass and enhancing the smoothness of the trajectory. Upon reaching flat ground, the reconfigurable wheel resumes its circular shape to improve travel efficiency. In contrast, during the ascent phase, \(q_1<q_2\), resulting in a different deflection angle for the rim. The ascent process is similar to that shown in Fig. 12 and will not be repeated here. The trajectory of the center of mass during the ascent is depicted in Fig. 20, demonstrating smooth motion and further validating the rationality and performance of the reconfigurable wheel design. In addition, the variations in motion parameters during the wheel’s ascent and descent of steps are presented in Fig. 21, which is highly valuable for a deeper understanding of the wheel’s motion and shape adaptation.

As shown in Fig. 22, the various attitudes of the reconfigurable wheel while crossing bilateral stairs highlight its impressive adaptability. The reconfigurable wheel can smoothly navigate the bilateral steps without altering the vehicle’s direction, simply by adjusting its wheel attitude. This capability is particularly significant for mobile robots operating in narrow spaces, as it allows for time-saving maneuvers and enhances task efficiency during execution.

The torque curves in Fig. 23a and b correspond to the conditions depicted in Fig. 22a and b of the paper, illustrating the torque variation trends when the reconfigurable wheel climbs left-side and right-side stairs of the same size. A comparison of the torque curves in Fig. 23a and b reveals that climbing left-side stairs requires a greater transformation torque. This phenomenon may be due to the fact that, during stair climbing, the input variable \(q_2\) drives the link \(l_4\) while \(q_1\) drives the link \(l_1\). The mechanism might be closer to a singularity point when climbing left-side stairs.

To demonstrate the superiority of the proposed reconfigurable wheel in terms of stability when overcoming steps, we built a model of the WheeLeR using CAD software and imported it into Adams for simulation analysis, as shown in Fig. 24. We have added a comparison of trajectories for the reconfigurable wheel and the WheeLeR robot overcoming a \(283mm \times 100mm\) step, as shown in Fig. 25a and b. From the comparison results, it is evident that the trajectory of the proposed reconfigurable wheel is smoother than that of the WheeLeR, indicating higher smoothness during obstacle traversal.

In summary, the experiments in this section demonstrated that the reconfigurable wheel can efficiently and smoothly navigate stairs, as well as adapt to bilateral stairs by adjusting its wheel attitude. This capability holds significant practical value for robotic applications in narrow spaces. Compared to passive and most active reconfigurable wheels, the design presented in this paper enhances motion smoothness and minimizes abrupt changes in the center of mass by effectively adjusting the wheel’s orientation. This not only improves the stability and accuracy of on-board sensors but also greatly enhances the overall stability of the robot.

Prototype validation

Based on the theoretical analysis and ADAMS virtual prototype simulation results, we designed and fabricated a physical prototype, as shown in Fig. 26. This prototype features two reconfigurable wheels, each equipped with dual degrees of freedom, powered by a total of four Unitree’s A1 motors-one for each degree of freedom. Additionally, MAXON motors were employed to drive the wheel rotation. The control platform for the prototype is an Orange PI core control board. The primary objective of this physical prototype is to validate the fundamental motion principles of the reconfigurable wheel and its performance in crossing steps and stairs. In this study, we prioritized the motion performance and adaptability of the reconfigurable wheel over addressing the balancing issues typical of two-wheeled mobile robots, thereby further verifying its effectiveness and advantages.

As shown in Fig. 27, we verified the reconfiguration motion mechanism of the reconfigurable wheel using the physical prototype. The PD control system facilitated precise adjustments to the wheel’s attitude. Various control commands were applied during the experiments, including maintaining a circular shape with a constant radius of 135 mm, increasing the radius alone, and rotating the wheel rim counterclockwise or clockwise while increasing the radius. Figure 27a–d illustrate the corresponding attitudes of the prototype. The experimental results demonstrate the reconfigurable wheel’s ability to accurately adjust its morphology based on these commands, confirming the rationality of its design and the reliability of our motion control system. These experiments not only validate the diverse reconfiguration capabilities of the wheel but also highlight its potential applications in navigating complex terrain.

Since crossing multiple consecutive steps can be seen as a repetitive action of overcoming a single step, we constructed a wooden platform, as shown in Fig. 28, to validate this task using the designed physical prototype. In the experiment, the reconfigurable wheel begins from a position 285 mm away from the step, gradually adjusting its morphology during movement to successfully navigate an obstacle that exceeds the wheel’s radius. After successfully crossing the step, the wheels return to a circular shape, ensuring that the robot’s subsequent movements remain efficient and stable.

Stairs are common obstacles in everyday life, and most wheeled mobile robots struggle to navigate them, often relying on elevators, which are not always available in factory settings. Our designed robot addresses this issue by smoothly traversing stairs using reconfigurable wheels. To test the adaptability of the physical prototype in a real environment, we conducted experiments on the staircase of the experimental building. The results demonstrated that the prototype successfully navigated stairs with specific dimensions of depth and height (300 mm \(\times\) 160 mm). As shown in Fig. 29, the physical prototype completed this task smoothly, further validating its practicality and reliability in real-world applications.

In summary, this chapter demonstrates that the designed dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel can smoothly navigate various staircase obstacles through a series of simulations and experiments. Various staircase configurations were modeled in ADAMS software, and the reconfigurable wheel successfully adapted its reconfiguration amount at appropriate times, allowing it to surmount different step sizes and handle complex scenarios involving varying step heights within the same staircase. This flexible adjustment results in a smoother overall motion trajectory. Additionally, the chapter highlights a unique advantage of the reconfigurable wheel: it can ascend and descend stairs without altering the vehicle’s direction, effectively climbing bilateral stairs. This capability enhances the wheel’s flexibility and passability compared to other designs. Finally, experiments with physical prototypes validate the structural rationality, reliability, and practicality of the reconfigurable wheel in overcoming step-like obstacles, showcasing its strong adaptability and potential for real-world applications.

Conclusions

To address the limitations of traditional wheeled mobile robots in efficiently navigating staircase-type obstacles, this paper introduces a modular dual-degree-of-freedom active reconfigurable wheel, leveraging parallel five-link structures and planetary wheel synchronization mechanisms. This innovative design allows the reconfigurable wheel to replace conventional wheels on most wheeled mobile robots, facilitating effective traversal on both flat surfaces and stairs, thereby offering a novel solution for mobile robot applications in complex environments. To evaluate the reconfigurable wheel’s capability in overcoming staircase obstacles, a detailed kinematic analysis is conducted, resulting in the establishment of a kinematic model. This analysis includes investigating potential interference during attitude adjustments and exploring the constraint relationships of the input variables. Ultimately, the study determines the range of obstacle sizes that the reconfigurable wheel can navigate without interference. This model enables automatic attitude adjustments based on varying step sizes by calculating the drive motor’s rotation angle in response to the steps’ depth and height, ensuring precise reconfiguration control. ADAMS simulations and physical prototype experiments confirm that the reconfigurable wheel can smoothly navigate staircases with varying step sizes, as well as handle the complexities of a single staircase featuring different step dimensions. Additionally, the mobile robot equipped with this reconfigurable wheel can smoothly overcome the stairs on both sides without altering its direction, and can also realize the task of going up and down the stairs. The prototype experiment results further validate the design’s rationality and innovation, demonstrating the effectiveness of the reconfigurable wheel structure.

However, due to limitations in the experimental environment, this study could not conduct large-scale prototype testing.In practical applications, various factors, such as friction and traction, significantly affect the ability of reconfigurable wheels to overcome steps. Insufficient friction between the wheels and the ground can severely compromise the stability of the robot. If the friction is inadequate when the wheels make contact with the step, slippage may cause the robot to lose balance, preventing it from ascending the step. In addition, insufficient friction can undermine the accuracy of the wheel shape estimation based on inverse kinematics, which is crucial for successfully overcoming steps. Therefore, ensuring sufficient friction is essential for maintaining stability and achieving reliable step-climbing performance.

Additionally, while the focus was primarily on the innovative reconfigurable wheel structure, the control algorithms for the robot itself were not thoroughly explored. Future work will concentrate on creating more representative experimental environments to further validate the prototype’s performance, as well as addressing the balance control challenges of two-wheeled mobile robots utilizing reconfigurable wheels. This approach aims to facilitate the transition from validation experiments to practical applications.

Data Availability

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Paddan, G. & McIlraith, M. Noise and vibration measurements in a viking military vehicle. Def. Technol. 17, 1976–1987. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2020.09.021 (2021).

Dimauro, L., Venturini, S., Tota, A., Galvagno, E. & Velardocchia, M. High-speed tracked vehicle model order reduction for static and dynamic simulations. Def. Technol. 38, 89–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2024.01.006 (2024).

Kubelka, V., Reinstein, M. & Svoboda, T. Improving multimodal data fusion for mobile robots by trajectory smoothing. Robot. Auton. Syst. 84, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2016.07.006 (2016).

Chanthasopeephan, T., Jarakorn, A., Polchankajorn, P. & Maneewarn, T. Impact reduction mobile robot and the design of the compliant legs. Robot. Auton. Syst. 62, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2016.07.006 (2014).

Bruzzone, L. & Quaglia, G. Review article: locomotion systems for ground mobile robots in unstructured environments. Mech. Sci. 3, 49–62 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Htec foot: a novel foot structure for humanoid robots combining static stability and dynamic adaptability. Def. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2024.08.010 (2024).

Jiang, H., Xu, G., Zeng, W. & Gao, F. Design and kinematic modeling of a passively-actively transformable mobile robot. Mech. Mach. Theory 142, 103591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2019.103591 (2019).

Luo, Z., Shang, J., Wei, G. & Ren, L. Module-based structure design of wheeled mobile robot. Mech. Sci. 9, 103–121. https://doi.org/10.5194/ms-9-103-2018 (2018).

Kim, D., Hong, H., Kim, H. & Kim, J. Optimal design and kinetic analysis of a stair-climbing mobile robot with rocker-bogie mechanism. Mech. Mach. Theory 50, 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2011.11.013 (2012).

Nakajima, S. Development of four-wheel-type mobile robot for rough terrain and verification of its fundamental capability of moving on rough terrain. In 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics 1968–1973 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBIO.2009.4913302.

Zhu, Y., Fei, Y. & Xu, H. Stability analysis of a wheel-track-leg hybrid mobile robot. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 91, 515–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10846-017-0724-1 (2018).

Luo, Z., Shang, J., Wei, G. & Ren, L. A reconfigurable hybrid wheel-track mobile robot based on watt ii six-bar linkage. Mech. Mach. Theory 128, 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmachtheory.2018.04.020 (2018).

Choi, D., Kim, Y., Jung, S., Kim, J. & Kim, H. A new mobile platform (rhymo) for smooth movement on rugged terrain. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron 21, 1303–1314. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2016.2520085 (2016).

Eich, M., Grimminger, F. & Kirchner, F. Adaptive compliance control of a multi-legged stair-climbing robot based on proprioceptive data. Ind. Robot. 36, 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/01439910910957084 (2009).

Eich, M., Grimminger, F. & Kirchner, F. A versatile stair-climbing robot for search and rescue applications. In 2008 IEEE International Workshop on Safety, Security and Rescue Robotics 35–40 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1109/SSRR.2008.4745874.

Eich, M., Grimminger, F. & Kirchner, F. Proprioceptive control of a hybrid legged-wheeled robot. In 2008 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics 774–779 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBIO.2009.4913098.

Vijaychandra, A., Alex, C., Mathews, M. & Sathar, A. Amphibious wheels with a passive slip mechanism for transformation. In 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM) 960–965 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICARM.2019.8833739.

Chou, Y., Yu, W., Huang, K. & Lin, P. Bio-inspired step-climbing in a hexapod robot. Bioinspir. Biomimet. 7, 036008. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-3182/7/3/036008 (2012).

Moore, E., Campbell, D., Grimminger, F. & Buehler, M. Reliable stair climbing in the simple hexapod ’rhex’. In Proceedings 2002 IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. (Cat. No.02CH37292), vol. 3 2222–2227 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBOT.2002.1013562.

Campbell, D. & Buehler., M. Stair descent in the simple hexapod ’rhex’. In 2003 IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. (Cat. No.03CH37422), vol. 1 1380–1385 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBOT.2003.1241784.

Qiao, G., Song, G., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. & Li, Z. A wheel-legged robot with active waist joint: design, analysis, and experimental results. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 83, 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10846-015-0303-2 (2016).

Kim, Y., Kim, J., Kim, H. & Seo, T. Curved-spoke tri-wheel mechanism for fast stair-climbing. IEEE Access 7, 173766–173773. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2956163 (2019).

Son, D., Shin, J., Kim, Y. & Seo, T. Levo: mobile robotic platform using wheel-mode switching primitives. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man 23, 1291–1300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-022-00696-1 (2022).

Kim, Y., Son, D., Shin, J. & Seo, T. Optimal design of body profile for stable stair climbing via tri-wheels. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man 24, 2291–2302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-023-00887-4 (2023).

Shin, J., Kim, Y., Kim, D., Yoon, G. & Seo, T. Parametric design optimization of a tail mechanism based on tri-wheels for curved spoke-based stair-climbing robots. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man 24, 1205–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-023-00817-4 (2023).

Kim, K. & Seo, T. Fletbot, a flexible thermoplastic polyurethane applied tri-spiral spoke wheel robot. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Man 25, 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12541-023-00830-7 (2024).

Bai, L., Guan, J., Chen, X., Hou, J. & Duan, W. An optional passive/active transformable wheel-legged mobility concept for search and rescue robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 107, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.robot.2018.06.005 (2018).

Zheng, C. & Lee, K. Wheeler: Wheel-leg reconfigurable mechanism with passive gears for mobile robot applications. In 2019 IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 9292–9298 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2019.8793686.

Sun, J. A novel design of the intelligent stair-climbing wheelchair. In 2020 6th International Conference on Mechanical Engineering and Automation Science (ICMEAS) 217–221 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMEAS51739.2020.00047.

Zheng, C., Sane, S., Lee, K., Kalyanram, V. & Lee, K. \(\mathbf{\alpha }\)-waltr: adaptive wheel-and-leg transformable robot for versatile multiterrain locomotion. Ieee T Robot. 39, 941–958. https://doi.org/10.1109/TRO.2022.3226114 (2023).

Kim, Y., Jung, G., Kim, H., Cho, K. & Chu, C. Wheel transformer: a wheel-leg hybrid robot with passive transformable wheels. Ieee T Robot. 30, 1487–1498. https://doi.org/10.1109/TRO.2014.2365651 (2014).

Kim, Y., Jung, G., Kim, H., Cho, K. & Chu, C. Wheel transformer: a miniaturized terrain adaptive robot with passively transformed wheels. In 2013 IEEE Int. Conf. Robot. Autom. 5625–5630 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2013.6631385.

Ryu, S., Lee, Y. & Seo, T. Shape-morphing wheel design and analysis for step climbing in high speed locomotion. IEEE Rob. Autom. Lett. 5, 1977–1982. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2020.2970977 (2020).

Woolley, R., Timmis, J. & Tyrrell, A. Cylindabot: transformable wheg robot traversing stepped and sloped environments. Robotics 10, 569. https://doi.org/10.3390/robotics10030104 (2021).

Tao, Y. et al. Analysis of motion characteristics and stability of mobile robot based on a transformable wheel mechanism. Appl Sci 12, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122312348 (2022).

Shi, Y., Zhang, M., Li, M. & Zhang, X. Design and analysis of a wheel-leg hybrid robot with passive transformable wheels. Symmetry 15, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym15040800 (2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Design and motion analysis of reconfigurable wheel-legged mobile robot. Def. Technol. 18, 1023–1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2021.04.013 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Quattroped: a leg-wheel transformable robot. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron 19, 730–742. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2013.2253615 (2014).

Chen, W., Lin, H., Lin, Y. & Lin, P. Turboquad: a novel leg-wheel transformable robot with smooth and fast behavioral transitions. IEEE T Robot 33, 1025–1040. https://doi.org/10.1109/TRO.2017.2696022 (2017).

Wang, T., Sung, D. & Lin, P. Terrain classification, navigation, and gait selection in a leg-wheel transformable robot by using environmental rgbd information. In 2018 International Automatic Control Conference (CACS) 1–1 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/CACS.2018.8606730.

Dai, C. et al. Swhegpro: a novel robust wheel-leg transformable robot. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO) 421–426 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/ROBIO55434.2022.10011955.

Ma, T. et al. R-taichi: A quadruped robot with deformed wheels. In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA) 1221–1226 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICMA57826.2023.10215553.

Cao, R., Gu, J., Yu, C. & Rosendo, A. Omniwheg: an omnidirectional wheel-leg transformable robot. In 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 5626–5631 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS47612.2022.9982030.

Xu, Q., Xu, H., Xiong, K., Zhou, Q. & Guo, W. Design and analysis of a bi-directional transformable wheel robot trimode. In 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 8396–8403 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/IROS51168.2021.9636421.

Fu, Z., Xu, H., Li, Y. & Guo, W. Design of a novel wheel-legged robot with rim shape changeable wheels. Chin. J. Mech. Eng.-En. 36, 153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-023-00974-7 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Step: a new mobile platform with 2-dof transformable wheels for service robots. IEEE ASME Trans. Mechatron 25, 1859–1868. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2020.2992280 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Key Special Projects of Heilongjiang Province’s Key R&D Program(NO. 2023ZX01A01) and Heilongjiang Province’s Key R&D Program: ’Leading the Charge with Open Competition’(NO. 2023ZXJ01A02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.: Project administration,Y.W.: Writing-original draft, Investigation, Resources,Validation. T.F.: Writing-review and editing,Conceptualization. C.W.: Writing-review and editing. H.W.: Writing-review and editing, Validation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information 1.

Supplementary Information 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Wei, Y., Feng, T. et al. RWD-DOF: a dual-degree-of-freedom reconfigurable wheel design for improved robotic mobility. Sci Rep 15, 16360 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98239-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-98239-x