Abstract

In this paper, we provide an overview and comparison of devices used for optical waveguide-to-waveguide coupling including inter-chip edge couplers, grating couplers, free form couplers, evanescent couplers, cantilever couplers, and optical wirebonds. In addition, technology for efficient transmission of light through chips is discussed including guided mode and free form photonic vias for substrates including silicon, glass, and organics. The results are discussed in the context of potential applications including co-packaged optics switch packages, replaceable biochemical sensors, optically connected memory, optical computing, integrated quantum photonics, and integrated LiDAR systems to show possible improvements in energy efficiency, performance, and cost.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Photonic integrated circuits (PICs) have seen significant advancement over the past 40 years, highlighted by their rise to dominance in data center interconnects1 and the novel application of PICs in biochemical sensors2, light detection and ranging (LiDAR)3, photonic switching4, photonic computing5, and even chip based 3D printing6. While the high volume manufacturing of PICs has progressed significantly, evidenced by the fact that 103–105 devices can be integrated onto a single die1, their packaging, assembly, and testing has not. Common estimates hold PIC packaging, assembly, and testing responsible for 70−80% of the total cost of PIC manufacturing compared with only 20% for their electronic integrated circuit counterparts7,8,9,10 as shown in Fig. 1. Specifically, the data in Fig. 1a shows the breakdown for a state-of-the-art electronic system-on-chip (SoC), demonstrating that front-end-of-line (FEOL) and back-end-of-line (BEOL) fabrication processes in foundries dominates the spending of chip manufacturing11. Meanwhile, the data in Fig. 1b for PICs—in this case indium phosphide (InP)12—shows the situation reversed. Furthermore, the costs can be broken down by process as in Fig. 1c showing the most expensive processes for electronic fan-out wafer-level-packaging (FO-WLP)13, which is contrasted by Fig. 1d showing the percentage of total cost for packaging, assembly, and test processes in integrated photonics12. This discrepancy is not simply due to electronics die being substantially more expensive than photonics die overall—in fact, relatively simple PICs cost roughly equivalent to the most advanced electronic ICs. For example, a state-of-the-art electronic SoC fabricated on a 5 nm process node costs approximately $0.57 per mm2 14 to purchase from a fabless design firm before packaging, while a SiPh15 or InP PIC costs approximately $0.1–0.4 per mm2 16, respectively, before packaging for chip volumes in the several millions. This is reflected by the fact that when we look at an example electronic-photonic system, such a silicon photonic (SiPh) pluggable transceiver, the packaging, assembly, and testing still dominates the overall cost in comparison to the SiPh transmitter (Tx) or receiver (Rx) die and the required electronics die such as transimpedance amplifiers (TIAs) or other drivers8 as shown in Fig. 1e.

In (a), data for Samsung’s fan-out panel level packaging (FO-PLP) manufacturing of the Google Tensor G2 system-on-chip (SoC)11. The data in (b) shows similar data for the manufacturing of a fiber coupled, integrated InP PIC with modulators and detectors12. The data in (c) is for FO-WLP, but nonetheless provides information on a breakdown by process for electronic packaging cost drivers13. Similarly, (d) does the same breakdown by process for the InP PIC12. Finally, (e) provides the overall cost breakdown for a ubiquitous electronic-photonic system—a SiPh transceiver8

Current techniques in semiconductor packaging and assembly

Electronic packaging and assembly strategies

Understanding the current technology landscape in electronic and photonic packaging can help provide answers to as to why photonic packaging and assembly continues to prove a significant challenge. Starting in 1947 with the first discrete wire connection17 in the first transistor18 and continuing with the development of ball and wedge bonding in the 1950s by Bell Labs19, electrical components have been connected using gold (Au), aluminum (Al), or copper (Cu) based wirebonds in a serial process. Today, electrical wirebonds (a 1D architecture using the nomenclature from ref. 20) can be made with 35-μm pitch21,22 and a time per bond of ~0.1 s23 using automated tools24,25, and remain the most ubiquitous interconnect modality for applications requiring <103 connections. In the 1960s, IBM proposed26 and introduced27 the first parallel process for electrical interconnection with the advent of the flip chip solder connection (a 2D architecture). Specifically, ball grid arrays (BGAs) using solder bumps coined controlled-collapsed-chip-connections (C4 bumps)28 enabled multiple connections from a die to a printed circuit board (PCB) in a single bonding step. Over time, in order to effectively scale the number of connections made to the chip, flip chip packaging strategies became more advanced with the number of intermediate substrates scaling up, as in Fig. 2a, and the solder bump diameters scaling down, as in Fig. 2b, c. Thus, for high volume applications requiring >103 electrical connections to be made, flip chip technologies are typically used.

In (a), the evolution from wirebonding (1D) to stacked die (3D) shows the increasing complexity of wiring within packages368. The plot in (b) shows the progression of bump technology over time (data up to 2020 is from ref. 369, with data after 2020 and future projections from refs. 30,370 which was in part derived from ref. 371), while (c) shows cross sections of the bumps used today, with both figures demonstrating current bumping pitches of <10 μm are possible370. The images in (d) show the common bonding processes used during assembly, which depends on the bumps technology used

Currently, advanced electronic packages are typically composed of an advanced node electronic die bonded to a redistribution layer (RDL) or embedded bridge (called a 2.1D architecture) which is fabricated on an organic package substrate, or a die bonded to a silicon interposer which is bonded to the organic package substrate (termed 2.3D or 2.5D architecture depending on if the interposer is thick enough to have electrical vias or not)29. Typically, the purpose of adding RDLs, bridges, or interposers is to achieve a higher level of electrical fan-out within the package—these components contain no functional devices on them, only Cu traces or vias. The fan-out itself is achieved by scaling the bump technology as one goes higher into the package stack, with Cu pillar bumps at the die-to-interposer level having pitches <20 μm compared to the C4 connections between the package substrate and the board having >100 μm pitch30. Stacking of electrical die atop one another (a fully 3D architecture), a practice common in the packaging of advanced dynamic random access memory (DRAM) chips31 and complimentary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) image sensors32, is also possible. These 3D architectures target connection densities >104 connections per mm2 and bump pitches <10 μm by using through-silicon-vias (TSVs) combined with hybrid bonding33, which will be described below.

The processes used in the assembly and bonding of the above architectures can be grouped into four categories: mass reflow, thermocompression bonding (TCB), laser assisted bonding (LAB), and hybrid bonding. Cross sectional schematics showing the basic operation of each process can be found in Fig. 2d. The type of bonding process used depends on the type of bump used. For example, mass reflow, where die are assembled onto substrates using high speed, automated pick-and-place tools and then collectively heated in a reflow oven such that the C4 bumps melt and solidify, is often used in the case of C4 bumps where the pick-and-place alignment can be quite poor and still result in high yield. On the other hand, TCB, where pressure and heat are applied to the die during the pick-and-place step, is used with μ-bumps or Cu pillars where higher alignment accuracy is needed along with pressure in order to prevent or remove oxide films on the electrical bumps which lead to electrical failure. Because TCB is a serial process where one die is bonded after the next, the lower throughput34 for such processes is often seen as a substantial downside. As mentioned above, hybrid bonding is used with planarized, solderless Cu/dielectric interfaces to achieve the highest possible connection density. Hybrid bonding involves taking a surface composed of Cu pads and dielectric passivation (such as silicon dioxide (SiO2), silicon oxynitride (SiON), or silicon carbonitride (SiCN)), planarizing it using chemical mechanical polishing (CMP), activating the surface by applying plasma, and then bonding the dielectric surfaces and Cu surfaces such that the entire surface of each die is part of the bonding interface35. The hybrid bonding process can be done at the die level or wafer level, although the ability to determine known-good-die (KGD) prior to bonding led to the development of collective die-to-wafer (D2W) bonding36 (also called advanced chip-to-wafer bonding)37. Collective D2W bonding increases throughput while allowing for determination of KGD by performing high speed pick-and-place of die onto a carrier wafer bonded using a sacrificial bond material (a low time, low temperature process), and then collectively bonding all of the die on the carrier wafer to the target wafer in a single bonding step (a single long, high temperature process).

Of critical importance to each of the above bonding and bumping technologies is the role of the automated pick-and-place die and wafer bonders. These advanced tools allow for high accuracy die or wafer alignment simultaneously with high speed, and are often equipped with additional capabilities such as epoxy dispense, heated tips and stages, and ultraviolet (UV) curing lamps. As one might expect, there is a tradeoff between speed (i.e., throughput) and alignment accuracy on these tools, which becomes relevant when moving to increasingly smaller bump pitches. Standard pick-and-place tools used for die attach prior to mass reflow have alignment accuracies of 10–20 μm and throughputs upwards of 18,000 units per hour (UPH)38, with higher accuracy models being available for placement precisions <3 μm with speeds of >2000 UPH (assuming 1–2 s per bond)34 for TCB39,40, and the highest accuracy die bonders being able to align to <0.3 μm with speeds of 2000 UPH for hybrid bonding41. Wafer bonders usually offer an order of magnitude better alignment accuracy than die bonders, with tools offering precisions <50 nm for 300 mm wafers42 and post-bond accuracies of <150 nm shown experimentally for Cu–Cu interfaces43. At the research stage, firms are also moving towards panel level bonders in order to enable the full potential of substrates such as glass or organics which can be fabricated at the panel level44. For electronics, the combination of methods such as collective D2W or panel level assembly with hybrid bonding in 3D architectures, which has shown to be possible with <2 μm final accuracy45, could prove critical to continued exponential scaling of performance in the most advanced systems. However, the application of these advanced flip chip packaging techniques to photonics could prove to have an equal, or potentially larger, impact on future electronic-photonic systems.

Photonic packaging and assembly strategies

One of the primary barriers to cost-effective photonic packaging and assembly is the active alignment and bonding of single mode fiber (SMF) arrays to PICs using UV-curable epoxies in a serial fashion, increasing cost and limiting throughput. Active alignment is the process of bringing a fiber array (or die) close to another die, injecting light through the fiber, and constantly scanning the position of the fiber array until maximum output power is measured through a second fiber in the array connected using a loopback, as shown in Fig. 3a. Once the maximum output power is measured, the fiber array is typically bonded into position using UV-curable epoxies, and the fiber position must be actively maintained and manipulated during the curing process as the epoxy will shrink or expand while solidifying. The technique of active alignment is currently the accepted method for fiber-to-chip attach or chip-to-chip attach in integrated photonics46. This is contrast to passive alignment, the method ubiquitously used by high speed pick-and-place die bonders of electronic packaging, which relies only on locating alignment features (fiducials) to determine where the center of a component is, as shown in Fig. 3b, and then placing that component at a given coordinate47. Not only are current active alignment based packaging methods costly in photonics, but they are severely limited in terms of their ability to scale optical input/output (I/O), or the number of connections made to the PIC. For example, SMF arrays operating near datacom (1310 nm) or telecom (1550 nm) wavelengths have minimum pitches of 127 μm due to their 125 μm cladding as shown in Fig. 3c, meaning a maximum density of only 8 fibers per mm is possible. To add to this challenge, as shown in Fig. 3a, multiple input and output ports to the die must be consumed with alignment loopbacks—waveguides and fibers which serve no other purpose other than to ensure fiber attach can be accomplished.

In addition to the fiber attach process, another photonic packaging challenge is the integration of devices from separate materials into a single package or across a single die. Four primary techniques have been developed to address this as outlined in Fig. 4: hybrid integration48, micro-transfer printing (μ-TP)49, heterogeneous integration50,51, and monolithic integration52. The four strategies each have tradeoffs and vary in terms of their level of integration and maturity. For instance, hybrid integration (shown in Fig. 4a) fabricates die separately in optimized foundry process flows and then uses pick-and-place of die on a submount for connectivity. The process of μ-TP, shown in Fig. 4b and still in the proof-of-concept stage, operates similar to hybrid integration, except the pick-and-place happens at the device level using a specialized plastic stamp. Thus, devices are ultimately transferred across the entire target wafer with only a few pick-and-place steps. The processes offering higher levels of integration include wafer bonding (heterogeneous integration, shown in Fig. 4c) or epitaxially growing (monolithic integration, shown in Fig. 4d), or combining the two53, the new material and then performing standard lithographic patterning thereafter. While these techniques offer higher levels of integration, they present difficulties in terms of the co-processing of the SiPh and the non-native components and the ability to test or inspect the non-native components for KGD.

In (a), the hybrid bonding of PICs from a few example material platforms is shown. The devices from those different material platforms can also be integrated using other pick-and-place methods such as μ-TP in (b). The devices can also be integrated in the FEOL using wafer bonding (i.e., heterogeneous integration) as in (c) or epitaxial growth (i.e., monolithic integration) as in (d)

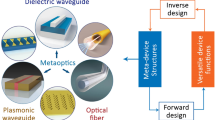

For solutions to the challenge of fiber attach and material integration, one needs only to look to microelectronics packaging where cost-effective I/O scaling is achieved using wirebonding or flip-chip connections depending on the number of connections needed. The development of optical equivalents to wirebonds, flip-chip connections, and electrical vias has therefore become a fervent research area, with the goal of improving the cost, size, weight, and power (C-SWaP) in photonic packages. As this research area is currently in its infancy, these optical equivalents are being developed without standards in terms of materials, processes, and performance metrics. To this end, it is useful to compile a database of available optical devices which can provide high-efficiency inter-chip connections. The term “inter-chip” refers to coupling from a single mode waveguide on a PIC (also referred to as a die or chip), interposer, or board to a single mode waveguide on a separate die, interposer, or board. Similarly, “intra-chip” refers to connections made between different layers of the same chip, and designs meant for intra-chip coupling through the bulk of a chip are referred to as photonic vias. In general, inter-chip optical coupling present substantial challenges versus intra-chip coupling such as needing to couple over >1 μm distances without high-resolution inter-chip alignment tools and difficulty associated with routing light out-of-plane. However, continued advancements in automated, pick-and-place die bonder resolution have demonstrated sub-micron placement accuracies with high speed using commercially available equipment54,55. Other bonding methods have evolved as well, including wafer scale processes such as collective die-to-wafer hybrid bonding56 or micro-transfer printing of thick components49,57. Novel fabrication techniques for creating on-chip 3D micro-optical components such as grayscale lithography (GSL)58,59,60,61,62, two-photon polymerization (TPP) lithography23, and surface controllable refractive index via beam exposure (SCRIBE)63,64 have unlocked integration possibilities not previously considered. Thus, with the need for optical I/O densities >8 connections/mm and C-SWaP scaling for ever more complex integrated photonic systems, inter-chip optical couplers have become a critical enabler for future PIC applications from the visible to the mid-infrared (mid-IR).

The design of these inter-chip connections would ideally meet the requirements laid out in Table 1 to be useful in practical applications and provide an improvement over fiber-to-chip packaging. These performance metrics will serve as the basis of comparison for these inter-chip couplers and a starting point for future comparisons. The following section discusses different types of inter-chip optical couplers and their operation.

Types of waveguide to waveguide couplers

The optical coupling designs proposed in literature for inter-chip coupling can be categorized into six different types: edge, grating, free form, evanescent, cantilever, and optical wirebonds. Schematics showing the general operation of these six types can be found in Fig. 5. Additionally, Fig. 6 shows values for each figure of merit, and for each coupling type, as defined in “Introduction”. The values for each figure of merit shown in Fig. 6 are averages taken over each data point in Tables 2–8. For the metrics of throughput and foundry compatibility, each coupling type was qualitatively assessed based on the fabrication, packaging, and assembly processes used (e.g., standard 193/248 nm deep UV (DUV) photolithography versus custom two-photon polymerization) and the materials required. The plot in Fig. 6 can be used as a guide throughout the following sections showing how coupling types compare against one another and which may be best suited for different applications. The remaining sections describe the operation of each coupling type, provide examples of notable designs and results, and present tables quantitatively comparing each coupler that was reviewed.

The images each show an example scenario of coupling between SOI waveguides (shown in red) on two separately fabricated chips, with (a) representing grating-to-grating coupling, (b) edge coupling, (c) evanescent coupling, (d) cantilever coupling, (e) free form coupling, and (f) optical wire bonding. The blue arrows indicate the direction of optical propagation before, during, and after coupling. Any pink structures in the images indicate components which are typically of a different material composition from the waveguides

The solid lines plotted for each coupler category represent averages for each figure of merit. This data was compiled based on the values reported Tables 2–8 of this study, with the exception of throughput and foundry compatibility. Specifically, the following references were used for each coupling class: edge75,76,78,79,81,82,83,88,89,91,163,322, grating100,101,102,124,126,127,128,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331,332, free form58,59,130,131,133,136,140,207,220,221,333,334,335,336,337,338,339, evanescent9,50,56,153,154,155,156,162,163,244,249,253,289,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350,351,352,353,354,355,356,357,358,359,360,361,362,363, cantilever164,165,166, and optical wirebonds64,163,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,193,364

Basics of optical coupling

The exact theory governing efficient coupling ultimately depends on the coupling design; however, a few common relationships can convey the relevant trends. To achieve efficient and alignment tolerant coupling, the incident and transmitted modes must be well size and shape matched, and reflections and misalignment should be kept to a minimum. The effect of these factors can be seen using the equation for coupling efficiency (η) between two overlapping modes65:

where β1, E1(r, ϕ) and β2, E2(r, ϕ) are the propagation constants (β = neffk0 and k0 = 2π/λ) and electric field distributions for the incident and transmitted modes, respectively. This is shown schematically in Fig. 7a for incident and transmission waveguides with refractive indices of n1 and n2, respectively. While obtaining analytic solutions to this equation is challenging even for relatively simple scenarios, by assuming the incident and transmitted modes are roughly Gaussian (\(E(r)={E}_{0}\exp (-{r}^{2}/{w}^{2})\) where w is the beam waist), we can numerically solve the integrals to gain insight. The results are shown in Fig. 7b which shows how mode size mismatch (w1/w2) and reflections (i.e., effective refractive index mismatch neff,1/neff,2) decrease coupling efficiency, with the size mismatch playing a more important role. Similarly, Fig. 7c highlights how modal misalignment impacts coupling efficiency while showing the typical scale of misalignments encountered for different fabrication processes such as wafer bonders, high accuracy pick-and-place tools, and ultra fast pick-and-place tools. Note that overlay misalignment in lithography is not plotted because the error is typically less than one-third of the critical dimension size (e.g., less than 30 nm for a 90 nm node process)66, and is thus can assumed to be less than 50 nm. It is interesting to note that symmetrically increasing the mode field diameter (MFD) of the incident and transmitted modes can increase alignment tolerance. As shown in the plot, the increase in MFD can occur by switching to material platforms which allow for a low refractive index contrast (Δn) such as ion exchange (IOX) waveguides on glass or polymer core/cladding in an effort to increase evanescent field size. Switching away from high Δn material platforms such as SiPh or InP has the downside of requiring larger waveguide pitches (to accommodate the larger MFD), and larger bending radii to maintain low loss routing across the die—both of which significantly impact the connection density of the circuit. This tradeoff—the desire for larger MFDs to increase alignment tolerance for chip assembly while simultaneously requiring smaller MFDs to increase connection and device density—is one of the most critical ones within photonic packaging. In the following sections, additional relationships critical to each coupling class will be presented in their individual sections, with the notion that modal overlap must be present in some level for every coupling type.

In (a), a diagram showing the concept of modal overlap between an incident waveguide with n1 (β1, w1) and a transmit waveguide with n2 (β2, w2) where some misalignment exists between the two modes. Meanwhile in (b), the effect of mode size mismatch and reflections are highlighted while in (c) the effect of misalignment and mode field diameter size

Edge couplers

Edge or butt coupling involves aligning coupling elements on separate die along the direction of propagation such that light does not change planes vertically. Like the fiber-to-chip case, the couplers are typically located along the edge of the PIC and require processing such as deep reactive ion etching (DRIE), or dicing and polishing, to create high-quality facets67. In addition, for inter-chip coupling, a separate process is typically needed to etch a trench in the lower die to properly align the couplers in the vertical direction. The inverse process could also be used—selective deposition of a mesa on the lower die achieves the same goal. In either case, when well aligned it is the minimization of reflection at the chip interface and matching of the size and shape of the mode between chips which enables low coupling loss. Numerous strategies have been employed to achieve low coupling loss in the context of fiber-to-chip coupling, including tapers with linear and nonlinear profiles, multi-tip (trident) tapers, multilayer silicon nitride (SiN) assists, cascaded multistage tapers, 3D tapers, suspended tapers, and sub-wavelength gratings68,69,70,71,72,73,74. Similar techniques have been employed for the inter-chip case, with inverse tapers, multi-mode interferometers (MMI), and graded index (GRIN) lenses being the most promising.

Inverse and standard taper couplers

Inverse taper designs decrease the waveguide width at the interface between chips, thus expanding the MFD and enabling lower coupling losses and wider alignment tolerances. In ref. 75, an InP laser diode was pick and placed using passive alignment with ±0.3 μm accuracy onto a SiPh die (labeled SiPho in Fig. 8a, b), showing 1.5 dB insertion loss using a InP to SiN inverse taper. A similar hybrid integration example from refs. 9,76 demonstrated an InP PIC pick and placed onto a Si die and passively assembled using solder self-alignment with 3D mechanical stops as shown in Fig. 8c, expanding the effective lateral alignment tolerance to ±25 μm. Both nonlinear inverse tapers and metamaterial tapers were compared experimentally, demonstrating chip-to-chip losses as low as 0.25 dB and 0.9 dB for the inverse taper and metamaterial taper, respectively76. Coupler simulations76 showed a 1-dB vertical misalignment tolerance of only ±0.5 μm and measured solder self-alignment data showed that a deviation of ±0.5 μm between the die and interposer could cause zero self-alignment to occur77. Other inverse taper designs have used index controllable silicon oxynitride taper claddings to provide efficient mode transformation from an InP semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA) to a silicon-on-insulator (SOI) die78. Multi-tip inverse tapers have also been used to connect an InP die to an SOI PIC79.

In (a) and (b), schematic and experimental images, respectively, of an inverse taper edge coupler from a SiN waveguide to an InP DFB laser passively assembled using pick-and-place tools (reprinted with permission from ref. 75 ©2023 IEEE). In (c), a side view of InP to SOI coupling is shown, where the red rectangle is the InP die and the gray etched shape is the SOI die. The black line across the InP and SOI is meant to show the waveguides on both surfaces being coupled. An experimental microscope image of the side view is shown on the bottom, demonstrating the submicron 3D alignment using mechanical stops (reprinted from ref. 372, ©2018 T. Barwicz et al. with permission from Elsevier and licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). In (d), a hybrid DBR laser based on flip-chip GaSb amplifiers and SOI waveguides is shown48 (©2022 N. Zia et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0). In (e), coupling between polymer waveguide layers using MMI devices92 (©2024 M. Weigel et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0). In (f, g), SOI to SOI or SiNx to SiNx flip-chip coupling using integrated GRIN lenses322 (©2025 D. Weninger et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Standard taper inter-chip edge couplers have also been used for chip-to-chip connections at mid-IR wavelengths80,81,82,83. For example, two die were mechanically aligned by interdigitating Cu nodules protruding from the chip’s edge and applying force horizontally to decrease the inter-chip gap size. To reduce index mismatch between germanium-on-silicon (GOS) waveguides, an arsenic trisulfide glass (n = 2.4 at λ = 8.4 μm) was dispensed at the interface80,82. Coupling losses of 4.1 dB at a 1.4 μm inter-chip spacing and 8.4 μm wavelength were demonstrated81. Couplers utilizing angled waveguides are also common when integrating active III-V devices to minimize back reflections into the gain area. Such a design is shown in Fig. 8d for a flip-chip, hybrid gallium antimonide (GaSb)-SOI laser at 2 μm wavelength with a simulated loss of 1.8 dB and estimated experimental loss of 5 dB48. Tapered spot size converters (i.e., standard tapers) can also be combined with the angled waveguides to improve coupling, such as in ref. 84, where an actively aligned GaSb-based SOA experimentally demonstrated 2.7 dB insertion loss to a SiPh die to form a hybrid laser from 1955 to 1992 nm wavelength. Simulated losses as low as 1.46 dB have been demonstrated for the same design and a similar wavelength regime near 1.9 μm85. Inter-chip edge coupling techniques have also been used in flip-chip hybrid integration of quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) with GOS waveguides for use in the 5.7–5.9 μm wavelength regime86 and μ-TP of GaSb-based gain elements to SiPh die for use near 2 μm wavelength87.

Multi-mode interferometer couplers

MMIs, traditionally used as on-chip splitters or combiners, can also be used to vertically couple between two separate layers of the same die or between two separate die. Such couplers, thus far only shown for intra-chip coupling, have included H-bar MMIs88, standard MMIs89,90,91,92,93, and edge assembled block MMIs94. The advantage of using MMIs is their inherent fabrication simplicity while allowing for vertical integration, at the expense of length sensitivity (due to the reliance on a mode resonance for efficient coupling) and longitudinal footprint. For instance, in refs. 91,93, and ref. 88, the total lengths of the MMI couplers are 3223 μm, 486 μm, and 241 μm, respectively. The vertical distance between waveguide layers can be significant though using MMIs, coupling over separations of greater than 20 μm with only 2.4 dB loss (which can be decreased to close to 1 dB according to simulation if lithographic alignment is improved)93. An image of a MMI design and its application to 3D photonic packaging are shown in Fig. 8e92.

Graded index couplers

Integrated GRIN lenses have also been proposed for efficient inter-chip coupling. Previously, SiON (also referred to as SixOyNz) GRIN edge couplers were experimentally demonstrated with fiber-to-chip coupling losses <0.5 dB from 1520 to 1640 nm while using standard foundry processes95. An expansion of this design enables inter-chip connections with simulations showing <0.5 dB total loss with a 1-dB bandwidth of >360 nm. The proposed GRIN inter-chip coupler is shown in Fig. 8f, g, where GRIN lenses are fabricated on separate die and flip-chip bonded. Moreover, the inter-chip GRIN coupler does not require the coupling to occur at the edge facet, allowing for 2D arrays of inter-chip connections, and it is able to accommodate an inter-chip gap size of >10 μm with a wide underfill refractive index tolerance. The GRIN coupler can also be paired with evanescent couplers to provide a universal interface for heterogeneous integration and fiber-to-chip coupling across material platforms. These advantages come at the cost of increased fabrication complexity, especially involving film stress management across the wafer.

In summary, the use of edge couplers for inter-chip connectivity has a number of advantages. Edge couplers can achieve <1 dB of loss over a wide wavelength window with polarization independence, and foundries include low loss edge couplers as standard process design kit (PDK) components96. However, they have larger footprints along the propagation direction as adiabatic tapers or MMIs can extend >1 mm9,76,78,88,91, along with a low misalignment tolerance made worse by potential for substrate leakage. The requirement that they be located at the edge with a high-quality facet also precludes them from being used in 2D arrays, thus limiting their I/O density.

Grating couplers

Grating couplers use a periodic etch with a period on the order of the wavelength of light to alter propagation direction by close to 90°. Parameters of grating couplers such as the grating period (Λ) and deflection angle (θ) are all directly tied to wavelength (λ) via the Bragg condition97:

where neff is the effective index of the waveguide mode and nout is the refractive index of the output medium. During fiber-to-chip coupling, the mode also typically undergoes spot size conversion to match the size of the waveguide mode, accomplished through an adiabatic taper. For inter-chip couplers, grating couplers are located on either die such that light enters into the lower die grating, diffracts upwards at an angle towards the upper die, and is coupled in plane upon incidence on the other grating. By changing optical propagation direction, the impact of the inter-chip gap size as well as its material (i.e., refractive index) are reduced. Enabling large vertical inter-chip gap sizes is important for several reasons: (1) it allows for simple electrical integration using standard Cu μ-pillar bumps or a similar variant, (2) it allows for thick BEOL claddings (>4–5 μm) with minimal effect on coupling efficiency, and (3) it increases the fabrication tolerance of the electrical interconnects (or other adhesive layer) as well as the BEOL thickness beyond the expected ±10%. The fact that grating couplers have been extensively studied in fiber-to-chip packaging98,99, are foundry compatible and found ubiquitously in PDKs96, and enable wafer level test, all combine to make grating couplers an appealing inter-chip coupling solution.

Several inter-chip grating coupler prototypes have been fabricated which highlight these advantages. Both Cu μ-pillar100 and In bump self-alignment101 have been used to achieve <1 μm lateral alignment of grating couplers on separate die. In ref. 100, the gap between the two die was 20 μm and was filled with air—demonstrating a high vertical and refractive index tolerance. In Fig. 9a, b, the cross sectional schematic and fully packaged system are shown for the In bump prototype101. A summary of inter-chip grating couplers is presented in Table 3. The presented data also illustrates a few of the challenges of grating couplers, including typical coupling losses above 3 dB, often made worse by substrate leakage for fully etched gratings. In addition, they suffer from high wavelength sensitivity with 1-dB bandwidths <±40 nm (with most <10 nm).

a, b Grating-to-grating couplers using In bump self-alignment (reprinted with permission from ref. 101 ©Optical Society of America). c, d L-shaped grating for topological unidirectional resonance with inter-chip wavelength response102 (©2024 H. Wang et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0). In (e), SOI to Si3N4 intra-chip grating couplers using top and bottom reflectors are shown (reprinted with permission from ref. 126 ©Optical Society of America)

A variety of strategies are available for improving inter-chip grating couplers. As discussed in ref. 102, fiber-to-chip packaging designs have used L-shaped103,104,105,106,107,108, interleaved109,110,111, multilayered112,113,114, overlayed115,116,117, and tilt-etched118,119 strategies to minimize the wasted downward diffracted light. The use of a bottom mirror120,121, distributed Bragg reflector122, or bottom multilayer reflector123 have all shown lower coupling losses, limited substrate leakage, and wider bandwidth for fiber-to-chip couplers as well. The apodization of gratings, or changing the period along the propagation direction, also helps reduce back scattering and tailor the MFD and scattering angle102. Using an optimized L-shaped geometry with apodization, as shown in Fig. 9c, has shown results of 0.94 dB with a 21 nm 1-dB bandwidth near 1550 nm for inter-chip coupling, as shown in Fig. 9d102. This wavelength dependency may be improved by using high index guiding vias which have a simulated 1-dB bandwidth as wide as ±100 nm near 1550 nm124,125. Adding a bottom mirror, as shown in Fig. 9e, has also shown improved performance for intra-chip coupling126,127 and has simulated similar improvements for inter-chip coupling128. While high index vias or bottom mirrors are generally not desirable, strategies which can combine such reflectors in a foundry compatible fashion would allow grating couplers to achieve even wider appeal as complete inter-chip packaging solution.

Free form couplers

Free form coupling describes the use of micro-lenses and mirrors to reflect light from an input waveguide out of plane and then reflect and/or focus the beam into the output waveguide on another die. Historically, semi-parallel fabrication techniques have been used for 45° mirrors, including laser ablation129 and dicing130 with specialized blades followed by a metal deposition to improve reflection. An example is shown in Fig. 10a, b where a 45° total internal reflection (TIR) mirror in an interposer polymer waveguide was formed using femtosecond laser ablation and the reflected light coupled to a chip level SiPh grating coupler131. Adding a microlens above the 45° mirror through RIE or polymer reflow can expand alignment tolerances, which is especially important for interposer to board connections where ball grid array solder bumps can have diameters of >100 μm132. Free form coupler designs using 45° TIR mirrors fabricated through other processes, such as angled focused ion beam (FIB), have been demonstrated as shown in Fig. 10c133. While FIB etching is often a serial process, it can be extended to parallel reactive ion etching (RIE) based processes with hard masks to create angled facets for vertical couplers134,135. Another approach is the use of self-assembled DNA pyramids as micro mirrors for out of plane coupling as shown in Fig. 10d, e136. The angle of the reflecting facet can be controlled by manipulating the lattice structure of the crystallite and the plane of that lattice structure which interfaces with the substrate136. Reflectivity can be further improved by coating the resultant self-assembled structures with a metal such as silver (Ag)136.

In (a, b), a 45° TIR mirror in a polymer waveguide is used to couple to an SOI grating on chip (reprinted from ref. 131, with the permission of AIP Publishing). In (c), a combination of a TIR mirror in InP and an SOI grating couple light between pick-and-placed InP die (reprinted with permission from ref. 335 ©Optical Society of America). d, e DNA self-assembled pyramids (reprinted with permission from ref. 136, ©2023 American Chemical Society). In (d), a schematic of how DNA forms faceted structures which can be used as out of plane reflectors. In (e), SEM images show how the facet angles can be controlled during self-assembly. In (f, g), a schematic and simulation data for a flip-chip coupler using TPP fabricated micro-reflectors are shown139 (©2023 S. Yu et al., licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). In (h), an experimental image of the reflector is shown which was used for fiber-to-PIC coupling (adapted with permission from ref. 141 ©2024 Chinese Laser Press). In (i), an SEM image showing a TPP fabricated micro-reflector connecting two separate chips which are not flip-chipped, but placed side-by-side142 (©2024 H. Huang, licensed under CC BY 4.0). In (j), a side view of a coupler fabricated using greyscale and NIL is shown58 (©2022 Nakamura et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0)

With the advent of multiple methods for 3D nanoscale lithography including TPP23, GSL, nanoimprint lithography (NIL)137, and thermal scanning probe lithography138, using curved micro mirrors and lenses for inter-chip coupling has become a feasible design strategy. An inter-chip coupler using TPP printed reflectors is shown in Fig. 10f, g139. Fabricating mirrors in RIE trenches is typical with free form couplers to center the reflector with the optical mode in the waveguide. In the simulations conducted in ref. 140, inter-chip coupling losses <0.25 dB were shown for coupling between polymer waveguides with a core (cladding) refractive index of 1.543 (1.525). Similar simulations in ref. 139 demonstrated <0.49 dB coupling loss between SiN waveguides. By using a curved reflector to simultaneously reflect and collimate, coupling losses can be significantly improved compared to 45° mirrors as wave front distortion is reduced140. These TPP based curved reflectors have been experimentally demonstrated for fiber-to-chip packaging as shown in Fig. 10h, coupling to a 0.220 × 1.5 μm SiN waveguide with a 4.9-μm-thick oxide cladding139 and to a 0.220 × 0.480 μm wide SOI waveguide with a 5.26 μm cladding141. They have also been experimentally demonstrated with <2.5 dB coupling loss for InP chip to SOI chip packaging without flip-chip bonding as shown in Fig. 10i142. Similar inter-chip couplers, shown in Fig. 10j, have been fabricated using GSL and NIL58,59,60,61,62. In this case, GSL was used to define micro-mirrors on an embedded SOI-PIC while NIL created 45° reflectors in a polymer RDL on an organic substrate.

One important benefit of employing mirrors and lenses is that they have low wavelength and polarization sensitivity. This can be seen by the 1-dB bandwidth and insertion loss columns in Table 4, showing bandwidths >±200 nm and operation from the visible (805 nm) and datacom/telecom regime (1310/1550 nm). Free form couplers also have small longitudinal footprints of <50 μm, although this is often larger in practice since adiabatic tapers in Si or SiNx waveguides are needed to increase the MFD59,139. Another advantage is that the vertical alignment tolerance can be expanded to >35 μm allowing for ease of integration with electrical interconnects. The lateral alignment tolerance can similarly be expanded by increasing the mirror size and thus the MFD of the collimated beam. Of course, increasing the mirror diameter limits the lateral channel density, a tradeoff relevant for applications requiring connection densities >50 couplers/mm. While the thermal tolerance of such micro-optic elements needs to be carefully considered, as they are often fabricated from polymers with low glass transition temperatures, it is feasible to use resins which can withstand reflow temperatures of up to 250 °C139.

The primary drawback of free form couplers using TPP or GSL is their serial fabrication. Printing using TPP or GSL requires one field to be written after another, with current write times often on the order of several hours to write tens of couplers23. While parallel grayscale exposures are possible using chrome masks with computer generated bitmap data143,144, the photoresist development rate must be linearly proportional to the exposure dose, restricting photoresist selection to specialized, positive tone resists. For TPP, write time can be improved by over 3 orders of magnitude using techniques such as the shell-and-scaffold writing145, projection-based light sheet exposure146,147, and multiple-beam parallel writing148,149,150. While the outlook of these techniques is extremely promising, other parallel processes, such as using a TPP master mold for NIL or hot embossing, may be required to scale to high volume packaging involving >103 optical connections.

Evanescent couplers

Evanescent couplers transfer optical power between waveguides by bringing them in close proximity and having the modal distribution’s evanescent tails interact. A conventional directional coupler with two side by side, parallel waveguides is a well-understood example97,151. According to Saleh and Teich97, 100% power transfer is possible if zero phase mismatch between each channel is present and the coupler length is set equal to the specific distance at which 100% power transfer is predicted to occur. Modifying this design can allow for minimizing the transfer length and the allowable misalignment between waveguides, usually by using inverse tapers, similar to edge couplers. A single, linear inverse taper can be improved upon, for example, by using a segmented taper instead152,153. Segmented designs divide the taper into multiple linear sections where adiabatic transfer occurs only in the segment where the mode effective indices of the upper and lower tapers are well-matched. Nonlinear tapers achieve a similar result through a continuous profile, but fabrication can be more challenging due to the lithographic accuracy required. Segmented tapers have been used for inter-chip coupling between several different material interfaces such as SOI to SiNx-on-glass152,153, SOI to IOX waveguides-on-glass154, and SOI to a flexible polymer ribbon155. Results have shown coupling losses <0.5 dB with alignment tolerances >±1.5 μm.

Other designs rely on angled tapers, where tapers on one die are intentionally rotated while tapers on the other are kept straight. As the die with the angled taper becomes translationally misaligned with respect to the straight waveguide, the angled taper remains overlapped with the same angle, thus not affecting coupling efficiency. Angled tapers expand translational alignment tolerance by at least 2.5 times compared to other couplers in Table 5, albeit at the expense of the pitch which is restricted to 15.3 μm for an angle of 4.4° and taper length of 200 μm156. A summary of different evanescent coupling designs can be found in Table 5, with a few of these shown in Fig. 11a–i.

a, b SiN on fused silica to SOI PIC (reprinted with permission from ref. 152, ©Optica Publishing Group). In (a), a perspective view of the coupler with the red indicating the double taper on the SOI PIC and the blue indicating the SiN double taper on the quartz interposer. In (b), a side view of an example fully packaged die showing the electronic-photonic integration of Cu micro pillar bumps as well as the use of an underfill epoxy for mechanical stability and refractive index matching. In (c), an IOX waveguide to SOI waveguide evanescent coupler cross section is shown along the propagation direction (reprinted with permission from ref. 154 ©2020 IEEE). d, e Polymer waveguide on board to SOI PIC. In (d), a perspective view of the coupler with the red indicating the multi-segmented taper on the SOI PIC and the blue indicating the polymer laminate on the board (reprinted with permission from ref. 373 ©2016 IEEE). In (e), a cross section of the evanescent coupler system with relevant parameters (reprinted with permission from ref. 374 ©2017 IEEE). In (f, g), SiN to SiN coupling with flip-chip Au–Au thermocompression bonding is shown including an oxide cladding opening on the interposer for decreasing the vertical gap between tapers (reprinted with permission from ref. 253 ©Optica Publishing Group). In (h), an SOI to Si evanescent coupler actuated by micro-electrical-mechanical system (MEMS) devices is shown along with how the coupler could be used as a switch for different layers or die (reprinted with permission from ref. 345 ©Optical Society of America). In (i), a cross sectional view of an evanescent coupler used to connect SOI waveguides to lithium niobate (LiNbO3) waveguides for modulator integration50 (©2019 M. He et al., reproduced with permission from SNCSC)

In addition to taper design, the material systems used play an important role in determining footprint, sensitivity to cladding refractive index, and minimum pitch. For instance, in a high index contrast (HIC) system such as SOI, a segmented taper with a 500-μm-long adiabatic region is required to achieve approximately 3 μm alignment tolerances152,153. In a low index contrast (LIC) system such as IOX-on-glass, the segmented taper requires a 1.5–2 mm adiabatic region to achieve the same alignment tolerance154. Likewise, in a LIC system with a Δn < 0.006154,155, the 1-dB tolerance for the adhesive refractive index was ±0.005 while for a HIC system with a Δn ≈ 0.5–2152,153 this tolerance increased by 15 times. This sensitivity also applies to the thermal tolerance—in a LIC system, a 1-dB excess loss penalty can occur if the cladding, substrate, or adhesive index changes by as little as ±0.003 due to higher operating temperatures154. A LIC system also restricts the minimum pitch to be >20 μm while HIC systems can scale further to <10 μm. Even a conservative pitch of 10 μm for SiNx or SOI waveguides results in a channel density of 100 couplers/mm compared to the 8 couplers/mm when fiber-to-chip packaging.

With that said, LIC systems remain desirable for low loss interfacing with SMF arrays, providing low propagation losses for optical redistribution, and fabrication maturity. For example, in ref. 154, the IOX-on-glass platform demonstrated an average of 0.68 dB insertion loss with 0.1 dB/cm propagation loss, while in ref. 155, the flexible polymer waveguides showed insertion losses of 0.3 dB (2.2 dB) at 1310 nm (850 nm) and propagation losses of 0.4 dB/cm (0.05 dB/cm) at 1310 nm (850 nm)155,157. Because these structures have also been fabricated and tested using foundry compatible materials, including reflow compatible laminates with siloxane based polymers155, and can be manufactured at the panel level, they are ideally suited for optical connectivity and redistribution at the board level following optical fan-out at the package level—a difficult challenge to address for future 3D photonic packaging technologies.

Furthermore, evanescent couplers have also been used for III-V-to-III-V or III-V-to-Si-PIC connections for integration of SOAs, lasers, or modulators. There exists a strong literature foundation in this area describing typical fabrication processes158,159,160,161, usually involving divinylsiloxane-bis-benzocyclobutene (DVS-BCB) wafer bonding of III-V to patterned Si followed by III-V patterning, or micro transfer printing of previously patterned devices using DVS-BCB bonding. Table 6 compares various evanescent coupler designs using wafer bonded or micro transfer printed devices, many of which use similar geometries to Si evanescent couplers. Vertical alignment tolerances are not typically reported, though the DVS-BCB layer thickness is usually <100 nm. The designs more common to III-V based devices are multistage couplers, which use multiple stacked layers for signal transfer, a technique useful when the refractive index difference between two waveguides is large or when large vertical gaps need to be overcome. For example, in ref. 162, a three stage coupler is designed to connect InP waveguides to Si3N4 waveguides which have an index difference of approximately 1.3–1.5. Multistage evanescent couplers were also used in ref. 163 to couple light between input Si3N4 interposer waveguides and SOI die waveguides, using a Si3N4 waveguide between the input and output layers. Such a multistage design could be used to overcome the thick BEOL layers by placing a taper structures midway through the BEOL as an intermediate layer.

In summary, as evidenced by the results in Tables 5 and 6, evanescent inter-chip couplers can achieve ultra low coupling losses of <0.5 dB across with bandwidths >100 nm and lateral channel densities >100 couplers/mm. These advantages can be had while using foundry compatible processes and, by optimizing taper design, can achieve micron scale alignment tolerances so automated pick-and-place assembly can be used. Evanescent couplers also have a few remaining challenges which future design improvements will need to address. For one, because they rely on the evanescent tail distribution, they are typically polarization dependent. In addition, while the longitudinal footprint can be minimized through taper design, these couplers still typically have longitudinal footprints of >100 μm due to the need for adiabaticity. Finally, while the vertical taper-to-taper gap can be effectively increased by using multistage taper designs, these still requires additional waveguide fabrication within the BEOL layers, adding to fabrication complexity.

Cantilever couplers

Cantilever couplers are formed by inducing a tensile stress in a waveguide film and/or cladding that has been released or suspended, eventually leading to the waveguide bending in the out-of-plane direction in order to accommodate the stress buildup. The tensile stress can be induced by several processing techniques, such as a thermal treatment164, ion implantation165, or deposition of different films to increase stress166. When two PIC die are flip chip bonded and the bent waveguides are aligned, light can propagate as if it were traveling through an out-of-plane S-bend. An example of a cantilever inter-chip coupler utilizing a thermal treatment method is shown in Fig. 12a–c with associated experimental data164. In this study, SOI cantilevers were created by patterning, SiOx cladding, and releasing the Si waveguides, and then annealing at 770 ∘C to achieve a 90° bend. The stress buildup occurs because of the stoichiometry—at high temperatures, the non-stoichiometric cladding releases impurities and densifies167, resulting in an increase in stress in the oxide cladding as compared to the 1 μm buried oxide (BOX) layer. Optical transmission data from Fig. 12c shows a wide 1-dB bandwidth from 1500 to 1560 nm. Although the vertical and lateral tolerances were only ±0.5 μm and 1.25 μm, respectively, these can be expanded by using an underfill adhesive with a refractive index closer to that of SiO2. Likewise, a standard 2–3 μm BOX could be instituted by depositing a thicker oxide cladding to increase stress buildup. Also, despite the high temperatures, data from ref. 164 of annealing temperature versus cladding thickness reduction suggests there is a temperature window from 200–400 °C which falls below BEOL thermal constraints, but is still hot enough to form cantilevers at <90° bends. This type of <90° cantilever was suggested as a method to improve post-bond vertical alignment in evanescent inter-chip couplers156, but further investigation is required in this area to verify its feasibility.

a–c Reference 164 (reprinted with permission from ref. 164 ©Optical Society of America). In (a), a schematic of the cantilever coupler. In (b), a side view of the packaged system showing the cantilevers on the top and bottom die and the measurement apparatus. In (c), the wavelength dependence of the cantilever coupler is shown for the TE and TM modes. d–f Reference 168 (reprinted with permission from ref. 168 ©Optical Society of America). In (d), a cross sectional view shows the material system of the ion implanted cantilever coupler for different cantilever taper lengths (VCW(40) stands for vertically curved waveguide with 40-μm long cantilever). In (e), a perspective view is shown of cantilever couplers fabricated using ion implantation. In (f), data shows the loss coupling from the cantilever to a lensed optical fiber for different polarizations and cantilever taper lengths (doubling these values can give a rough estimate for waveguide-to-waveguide coupling). In (g), schematics of a SiON cantilever edge coupler used for wafer level, automated probing of InP devices, and in (h), a top-down experimental image with SiON probe on the left and InP waveguides on the right, after passive assembly173 (©2021 X. Leijtens et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0)

Ion implantation165,168,169,170,171,172 has also been used to induce stress and create cantilever couplers as shown in Fig. 12d–f. The fabrication process involved patterning, cladding, and releasing SOI waveguides, followed by ion implantation perpendicular to the cantilever surface. The cantilever cladding was removed during the release process while the remainder of the die stayed protected—a critical step since ion implantation of Si can dramatically increase the propagation loss (40 dB/mm for a dose of 2 × 1015 cm−2)168. The ion implanted cantilevers were also tapered from 430 nm at the waveguide to 190 nm at the tip over a lengths of 5–40 μm165,168,169,170,171. Once the tapers were bent, the entire system was then cladded with a 2 μm plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) oxide and SiO2 index matched optical epoxy. A cross sectional view showing the material stack and fabricated couplers can be found in Fig. 12d, e. A minimum fiber-to-chip loss of ~3 dB was achieved for TE mode coupling from a lensed SMF at 1550 nm for a taper length of 5 μm (thus inter-chip loss would likely be ~6 dB). The data showing the effect of polarization, taper length, and wavelength can be found in Fig. 12f. While the loss is considerably higher than the thermally induced inter-chip coupler, the ion implantation coupler has an extremely compact footprint of <5 μm long and 3 μm high when bent.

The deposition of metal or dielectric layers along the surface of a suspended structure is also a method which can be used to for cantilever coupler formation. This concept has been demonstrated in suspended gallium arsenide (GaAs) waveguides with a polymer spot size converter being bent at 90° angles due to stress built up from Ni strips deposited on suspended GaAs166. To overcome the challenge of controlling the cantilever radii to better than ±10 μm, self-alignment structures involving hooks lead to a mechanical forcing of proper bend angle simply by changing the pattern mask. This mechanical structure preserved alignment for cryogenic temperatures when the film stresses would otherwise lead to further cantilever bending. The performance of such cantilever couplers when coupling to a 1.5 μm MFD SMF, can be found in Table 7 alongside other designs. While the measured insertion losses were high, measurements relied on light focused from an objective lens rather than direct fiber coupling, likely resulting in higher coupling loss. The vertical distance from the surface of the chip to the tip of the bent cantilever was also ~100 μm—a substantial vertical gap size. The measured insertion loss also changed by only ~2 dB when measuring at 10 K, indicating the usefulness of such a design during cryogenic operation.

The prototypes involving thermally induced strain, ion implantation, and metal induced strain show that fiber-to-chip cantilever couplers can be used inter-chip coupling by using flip-chip assembly. Cantilever based designs with a released waveguide on only one die have also proven useful for the development of novel probes for high speed photonic testing173. As highlighted by Fig. 12g, h, released SiN waveguides based on the LioniX TriPleX platform174 were used to couple to wafer level InP waveguides at a density of 40 connections per mm using self-aligning etched pits for passive assembly173. The throughput and robustness of the cantilevers are noteworthy, as an array of 32 cantilevers was able to be automatically aligned from a park position in less than 3 seconds and repeated over 2500 times without failure173. These couplers allow for large inter-chip gap sizes while using parallel fabrication processes and achieving low coupling loss. Additionally, if a large area were used to release a cantilever array, the minimum pitch would then be only limited by the cantilever MFD, allowing for high lateral channel densities of >100 couplers/mm. They do, however, include narrow lateral alignment tolerances, fragility in the absence of a sufficient cladding, and high temperature BEOL process requirements depending on the design used. To address these challenges, further studies are necessary. Technologies such as MEMS devices may offer higher control of bending radii or post-bond self-alignment, while different materials such as SiNx might lead to wider alignment tolerances due to an increased MFD. This may also include the development of novel, stress controllable cladding materials to reduce thermal requirements and methods to limit the implicit tradeoff between ion implantation dose and optical propagation loss.

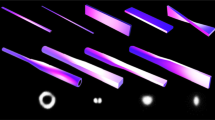

Optical wirebonds

Optical wirebonds are a versatile connector for low to intermediate volumes and are the optical equivalent to the electrical wirebond. These connectors can be polymer waveguides fabricated using TPP175,176,177,178, direct laser writing in mesoporous media64, polymer dispensing with open-to-air drying179, UV direct write lithography180, or flexible ribbon-based processes181,182,183,184,185. The first of these methods, TPP, produces couplers referred to as photonic wirebonds (PWBs), which can be found in Fig. 13a, b175,176,177,178. The chip-to-chip coupling performance showed a 1.6 ± 0.13 dB wavelength-independent coupling loss from 1530–1565 nm while the full spectrum from 1280–1580 nm demonstrated 2.5 ± 1.1 dB of loss. The primary advantage of PWBs is that because the structure is defined during the TPP process, which is completed after the two die have been bonded, the misalignment between waveguides becomes irrelevant. Robustness to mechanical vibration and shock was also demonstrated through a successful 1-meter drop test, which can be improved further by encapsulating PWBs in a rigid low index cladding.

a, b Photonic wirebonds (PWBs)178 (reprinted with permission from ref. 178 ©Optical Society of America). In (a), the mechanism of TPP printing of PWBs for chip-to-chip coupling. In (b), an SEM image of one of the PWBs coupling SOI to SOI. c, d Direct optical wirebonds (DOWs) (reprinted with permission from ref. 179 ©Optica Publishing Group). In (c), the mechanism of printing the DOW for chip-to-chip coupling using a micro-machined glass nozzle. In (d), microscope images of the fabricated DOWs. In (e), a schematic view of SmartPrint technology including the graded index profile for the polymer waveguides and a cross sectional view of the IOX waveguides with polymer cross tapers (reprinted with permission from ref. 180 ©2022 IEEE). f, g 3D ULI waveguide couplers (reprinted with permission from ref. 163 ©2018 IEEE). In (f), a schematic of 3D ULI fabrication along with a zoomed in view of the end terminations for SiN-to-ULI waveguide coupling using adiabatic tapers. In (g), a cross section of ULI waveguides fabricated in commercially available eagle glass substrate and LPCVD oxide cladding with the measured optical mode profile. In (h), the SCRIBE technique is shown for forming free standing micro-optic devices in mesoporous silicon64 (©2020 Ocier et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0). In (i), a schematic of the flexible paralyne waveguide with mirror end facets for optical connections185 (©Reddy et al., licensed under CC BY 4.0)

The second method, the use of a dispensed polymer which dries when it comes into contact with air, has been termed the direct optical wirebond (DOW)179. In fabricating a DOW, a polystyrene powder dissolves in xylene solvent is dispensed from a glass nozzle. The speed and direction at which the nozzle retracted away from the surface determine the size and shape of the wirebond. As the polystyrene solution is dispensed and the nozzle pulled upward, the xylene rapidly evaporates and leaves a solid, optically transparent, well adhered, and geometrically tapered polystrene wire as shown in Fig. 13c, d. The best experimental insertion loss using this method was measured to be 5.8 dB at 1590 nm wavelength when using a wire terminated with a grating coupler. The 1-dB bandwidth was estimated to be less than 10 nm due to the resonance between input and output gratings. The 1-dB alignment tolerance of the DOW to the grating was demonstrated to be >2 μm in simulation. Unlike the PWB case, this was relevant because DOW is likely to be implemented using an automated dispense tool have tolerances of 1–10 μm. By rotating the nozzle 90° during the pulling motion, the DOW can be attached to orthogonal surfaces such as SMFs or chips attached in different orientations. One primary downside of a DOW is that, because of the nature of the deposition method, the control over the shape and size of the wirebond is greatly sacrificed when scaling to smaller feature sizes.

A hybrid between a PWB and an evanescent coupler is what is called “SmartPrint" technology180. This variant is made by bonding a Tefzel film to a glass substrate and patterning evanescent poly(F-SBOC) couplers (see ref. 186 for material information) using Heidelberg UV direct write lithography tools and spatially varying the exposure dose. This technique is useful for forming a 2D connection between different substrates as shown in Fig. 13e. The poly(F-SBOC) tapers are grayscale tapers, meaning the geometry remains rectangular but the refractive index is tapered from 1.482 to 1.490 by varying the exposure dose over a 2 mm length. As was discussed in “Cantilever couplers” section, because IOX-on-glass is a LIC system, precision control over the refractive index of the grayscale taper is required as the tip is designed to be 0.003 below the IOX waveguide core and the poly(F-SBOC) input is 0.01 above the IOX waveguide core. Still, the lateral misalignment tolerance is effectively irrelevant because alignment between poly(F-SBOC) tapers and IOX waveguides is done lithographically.

Another hybrid which is a combination of an optical wirebond and an edge coupler is a 3D ultrafast laser inscription (ULI) waveguide187,188,189,190,191. In 3D ULI, a waveguide is directly written in a transparent medium by scanning a pattern using a pulsed laser with a pulse width on the order of femtoseconds192. Because the pulses have an electric field strength which is roughly equal to the field strength binding valence electrons to the atom (order of 109 Vm−1, or a laser intensity of 5 × 1020 W/m2), nonlinear absorption processes can cause avalanche ionization where electrons have enough kinetic energy to excite other electrons. This total energy is then transferred to the surrounding lattice to make permanent, local volumetric changes of the refractive index, creating waveguides192. Because the process relies on avalanche ionization, a wide range of transparent media can be used including PECVD or low pressure chemical vapor deposition (LPCVD) oxide claddings163. These waveguides have the benefit that they are instantly embedded in the material they are written within, and they can fabricated before or after die pick-and-place. Waveguides fabricated using 3D ULI have simulated interfacial losses to Si3N4 waveguides as low as 0.04 dB by terminating the ULI waveguide atop an adiabatic Si3N4 taper as shown in Fig. 13f, g163,193. Similar to other LIC systems, 3D ULI can form low loss connections to SMF arrays or MCFs and demonstrate propagation losses on the order of 0.3–0.8 dB/cm163.

Traditional 3D ULI can be taken further using the SCRIBE method63,64,194. This technique, shown in Fig. 13h, enables submicron control of the 3D refractive index profile by tailoring the amount of polymer remaining in a mesoporous silicon-based scaffold after exposure63,64,194. Steady improvements have resulted in SMF-to-SCRIBE waveguide losses of <0.45 dB with 3-dB alignment tolerances of >3 μm for SMF-to-chip vertical gaps of >37 μm64. The PWB, DOW, SmartPrint, ULI, and SCRIBE processes are highly customizable, making them well-suited for prototyping environments. However, their fabrication is still a serial process with connection densities <100 couplers/mm, limiting their current use to low volume manufacturing similar to electrical wirebonds.

Flexible polymer based ribbons also offer a way to make connections across large distances with a pre-patterned component. The flexible ribbons usually terminate with a type of coupler mentioned elsewhere in “Types of waveguide to waveguide couplers” section such as a free form or evanescent coupler. For example, in refs. 181,182,183, die-to-board connections were made through a board level evanescent coupler and a die level 45° TIR mirror fabricated via dicing with a double 45° V shaped blade. The evanescent coupler was created by removing the waveguide cladding on the ribbon and board, and pressing the ribbon into the board waveguide with a tool tip of a specific radius, resulting in coupling ratios of approximately 0.3–0.65 (6.36–4.04 dB loss). Another flexible ribbon includes that found in Fig. 13i which uses paralyne C waveguides with 45° reflectors at the waveguide termination184,185. This design also allows for electrical integration on the ribbon by depositing platinum traces atop a PDMS cladding. Simulations of the 30 lowest order modes for a paralyne C waveguide showed <3 × 10−10 dB/cm additional losses caused by the platinum layer interactions for the fundamental mode. This type of opto-electronic flexible ribbon could be used for implantable or wearable biophotonic devices used to probe tissue which otherwise would cause damage when integrated using rigid substrates195.

Photonic vias

Thus far, the discussion has been in the context of inter-chip couplers which transfer light from the surface of one die to the surface of a separate die; however, another category of couplers are those which connect waveguides on the front and back surface of the same die by transferring light through the substrate. This also includes couplers which connect waveguides on separate die by guiding light through a third substrate in between them. These photonic vias are distinct from simple intra-chip couplers, as intra-chip coupling distances are typically short (i.e., <5 μm) and can be accomplished through typical evanescent196, grating126, or edge coupling88 techniques. We can further categorize photonic vias into two different types: guided mode vias and free form vias. In guided mode vias, a via is etched and filled to form a vertical waveguide which light is then coupled into. In a free form via, light is reflected and collimated using micro-mirrors, but is not guided by a waveguide inside the via. In the next two sections, designs for each type of coupler will be presented.

Guided mode vias

To date, there have been few examples of guided mode vias explored. Those that have been developed can be further subdivided into polymer based vias and silicon based vias. A potential fabrication process for a silicon based via in thin Si substrates was outlined in ref. 197 and is shown in Fig. 14a. This process is executed during the same step as the etching of the electrical TSVs, where a DRIE step with an SiO2 hard mask simultaneously etches electrical TSVs and through silicon photonic vias (TPSVs). The diameter of the Si core of the TSPVs are 5 μm and the etch depth is 50 μm. The TPSV trench was filled with SiO2 to isolate the Si core and form a vertical multimode Si waveguide. Similar to a typical electrical TSV process, the backside of the wafer is thinned such that the bottom of the 50 μm TPSV is exposed. A cross sectional image showing the TSV and TSPV alongside one another can be found in Fig. 14b. This process results in the measured near field pattern (NFP) is shown in Fig. 14c, which demonstrated high confinement of light inside the Si core region versus the die which had no TSPV at all. To couple light into the TSPV at the entry or exit, the use of Si grating couplers with Ag reflectors was proposed. Simulation results using 2D finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) show coupling efficiencies as high as 73.7% (1.32 dB loss) for TE polarized 1550 nm light when using the Ag reflector, and efficiencies as low as < 5.5% (11.3 dB loss) when no mirror or TSPV were used. These efficiencies were for one end of the via, so additional loss is expected when including both input and output. Based on the reported data, the TSPVs aid in modal confinement, but are not necessary to obtain moderate coupling efficiencies (>50%). This is important when considering the process constraints required for DRIE as well as wafer thinning procedures.

a–c Si guided mode vias using a grating coupler (reprinted with permission from ref. 197 ©2011 IEEE). d, e A Si guided mode via using a 45° reflector (reprinted with permission from ref. 163 ©2018 IEEE). f, g A polymer guided mode via using 45° reflectors (reprinted with permission from ref. 201 ©2015 IEEE)

Another silicon guided mode via design uses 45° SOI TIR reflectors to couple light in and out of a-Si vias formed in SiO2 claddings as shown in Fig. 14d163. By optimizing the mirror offset (75 nm), the gap (1.3 μm), and the via width (d = 450 nm in Fig. 14d) losses as low as 1.3 dB were achieved163. The fabrication involved tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAH)-based Si etching to form 45° reflectors, followed by RIE and a-Si deposition to form the via198—fabricated vias with reflectors can be found in Fig. 14e. Although the via was fabricated in an SiO2 cladding, a similar concept could be used in thin glass substrates. The challenge for via formation in thin glass would be the high aspect ratio deep SiO2 etching (>50 μm) required to form single mode a-Si waveguides with diameters <1 μm. Additional studies would also be needed to ascertain the via propagation loss as simulations in ref. 163 suggest the vias are lossy (>3 dB) above 2-μm thicknesses. Lastly, with the advent of TPP, GSL, and NIL, implementing more efficient reflectors could provide improvements in coupling efficiency and bandwidth.

Polymer based vias offer another option for coupling of light through a chip199,200,201,202. Polymer via designs also use 45° TIR mirrors used to couple light into the via as outlined in Fig. 14f. An example fabrication process outlined in ref. 201 utilized thin glass substrates (150-μm thick), with inclined lithography to pattern the 45° TIR mirrors, resulting in the mirrors shown in Fig. 14g. Inclined lithography offers advantages over GSL and the moving mask method because it does not require a precise exposure gradient and positive and negative photoresists can be used. Furthermore, 2D FDTD simulations determined the losses at 850 nm for a 60 μm diameter via (n = 1.511) in a 100 μm glass substrate (n = 1.503) capped with 50 μm square multimode polymer input and output waveguides. The data showed that 0.5 dB loss was achievable if the mirror angle was kept within ±5° of 45°. Experimental data from ref. 202 demonstrated the vias also show <1 dB of loss for thicknesses >100 μm as well. Fabrication challenges of this design included difficulty in patterning 45° features in air due to the large index contrast, a zero gap mask requirement, and multiple exposures. Solutions include partial substrate immersion in water during exposure and using the glass substrate simultaneously as the mask by having a deposited Cu layer act as a zero gap mask. These solutions provide initial steps towards a parallel lithography technique for angled features, although the process has thus far been constrained to thin with non-transparent substrates being an open challenge. Further study is also needed to address increasing the polymer refractive index and reducing via diameter, leading to higher channel densities. Development of guided mode vias with LIC foundry compatible materials such as SiO2, SiON, or SiN will also enhance integration and adoption. This may require innovative thin film deposition techniques to eliminate voids or high index spin-on variants, like spin-on-glass203 or polymer via filling204.

Free form vias

Designs for free form vias typically involve a TPP or GSL mirror, a 45° mirror, or a grating to reflect light at 90° into the substrate. From there, the opposite surface may have another reflector for coupling between layers of the same chip, or it may have a micro lens to collimate the beam such that it can be directed towards a third, flip-chip bonded die. Designs tackling the latter challenge are important for future 3D integrated photonic packaging, because much of the current focus hasted rested on chip-to-chip or chip-to-interposer coupling without addressing optical chip-to-board and interposer-to-board connections. Two factors make this difficult: a sizeable vertical distance (>>100 μm) and a large refractive index difference between on-chip or on-interposer waveguides and board level waveguides. Designs utilizing free form vias could provide a path forward to overcoming these two challenges in future optical printed circuit boards using fiberless technology. Moreover, a variety of studies have investigated the performance of fully etched air vias versus propagation through transparent substrates205,206,207,208. Because different interposer materials are all widely used including silicon, glass, and organic substrates, separate sections will cover each situation individually.

Glass interposer vias

Glass interposers are appealing due to their advantageous thermal, mechanical, electrical, and optical properties. In addition, glass can be processed at the panel level, providing a scalable option in terms of cost and throughput. For free form vias, glass interposers have potential due to their high transparency in the visible and NIR wavelength regimes. This helps to eliminate the design and fabrication challenges associated with determining a suitable optical via material and etching through glass vias (TGVs). To elaborate, a number of methods have been explored to etch high quality TGVs including sand-blasting209, photosensitive glasses210, focused electrical discharging211, DRIE212, laser ablation213, and deep wet etching214. Of the most promising are wet etching processes whose directionality is enhanced by pulsed laser exposure. These techniques involve either inducing microstructural changes followed by wet etching215 or locally exposing an absorbing organic solution such that the glass is melted at the solution interface216. The drawback of such techniques is that they are serial processes compared to the Bosch process utilized in TSVs. Parallel processes are available, such as UV exposure and baking of photosensitive glass substrates, which changes the exposed area to a ceramic to be wet etched and form high aspect ratio features217. The extinction coefficient k, and therefore propagation loss, has not been characterized for HIC systems on photosensitive glass though. Therefore, optical TGVs which do not require such etching is an advantage and helps make the design agnostic to the type of glass used.